The Road to Cambridge

El camino de Cambridge

Luciano Concheiro

English translation by Tanya Huntington

After resigning as Ambassador to India in protest of the military repression of university students that took place on October 2, 1968 in Tlatelolco Square, Octavio Paz spent a year at Cambridge University. Before now, this stage in the life of the Mexican poet and future Nobel Laureate has remained practically unknown. In this brief essay, Luciano Concheiro contributes new information and helps clarify certain aspects of Paz’s historic resignation, which continues to inflame passions even today.

Having abandoned the Mexican embassy in India, Octavio Paz and his wife, Marie José, lived for several years in voluntary exile. Naturally, their decision sparked discontent among adepts of the regime, who wasted no time in unleashing an acrimonious campaign against Paz. To return to Mexico would have put him in a thorny situation, to say the least. As he would later explain to Julio Scherer:

I did not believe it would be sane to return to Mexico right away. Government hostility aside, I would have found myself embroiled in sterile and circumstantial disputes with public power and, moreover, with the opposition. I decided to wait a little while longer: it was clear that the repression would not be ongoing and that soon, spaces would be freed up that would enable criticism and debate. (1)

Paz would find the refuge he so desperately needed in three Anglo-Saxon universities: Pittsburgh, Austin and Cambridge. There, he would dedicate his time to writing, but also to teaching –an exceptional practice, in his case. This would be, as he himself would underscore in a later interview, his “first and last university experience.” (2)

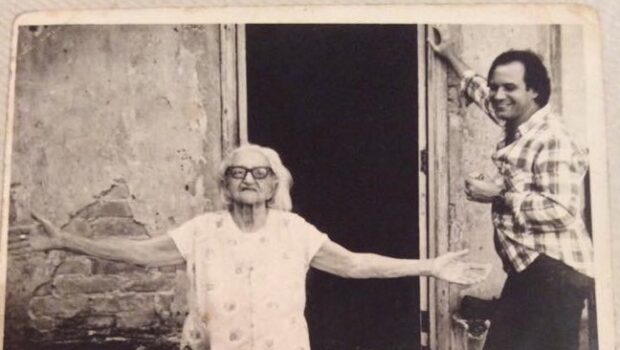

His stay in Cambridge would turn out to be the most significant of them all. Not only was it the university where he remained the longest and where he would reside before finally returning to Mexico in 1971: there he would also perform the soul-searching that finally led him to make that decision. In Cambridge, Paz realized he had two dialogues pending. The first was with his mother: Josefina Lozano was elderly, and he wanted to accompany her during her twilight years. The second was with his country: he felt he could not abandon Mexico at this critical juncture. Cloistered in an ivory tower, he could have led a comfortable, peaceful life; but to forsake his country seemed like a betrayal. In his own words: “Yes, living abroad I could have written with greater tranquility, but to abandon Mexico under those circumstances would have been more than evasion: it would have been treason.” (3)

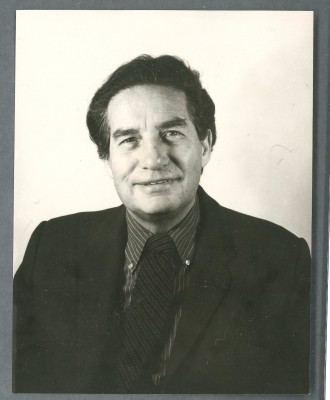

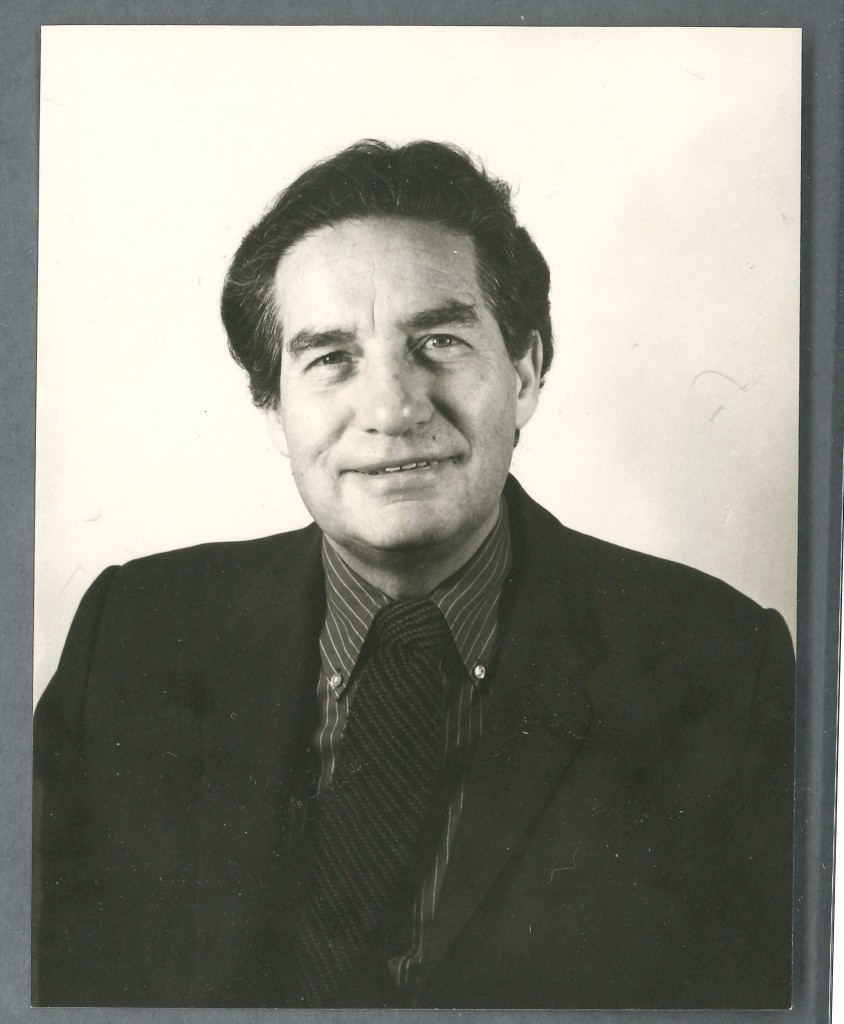

Not long ago, prompted by a single telephone conversation and a series of rainy afternoons, I decided to follow the paper trail of Paz’s passage through Cambridge. Scattered among several archives, I discovered a series of documents related to his stay at this University. (4) With the exception of a photographic portrait and a couple of postcards, they are essentially administrative; and yet they also provide important data and shed light on various aspects of Paz as a person of note during that era. They show, on the one hand, the considerable prestige he enjoyed abroad starting in the 1960s, and on the other, the existence of an efficient, international network of intellectuals that developed around him. Lastly, they prove something that turns out to be key in the recently revived debate regarding Paz’s resignation from the Embassy in India: his action was interpreted abroad as a severe critique of the Mexican government. If we change our perspective in this debate and instead of centering on Paz’s motivations and intentions, analyze the effects of his decision, it becomes indisputable that his was a historic protest in response to the events that took place on October 2nd at Tlatelolco.

It would seem Paz mailed his letter of resignation together with a large quantity of others that sought employment. On October 18, 1968, the wheels had already been set in motion to find him a position in Cambridge. He had written to the poet Nathaniel Tarn, expressing his desire to spend time in England and asking whether some local university might employ him on the subjects of Hispanic or Latin American literature. Tarn, in turn, informed George Steiner of the matter. It was, in fact, Steiner who decided to intercede on Paz’s behalf with University of Cambridge officials.

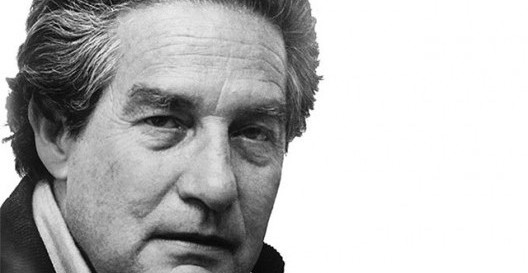

A previously unpublished picture of Octavio Paz. Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Churchill College

Steiner proceeded to send a letter to Sir William Hawthorne, a renowned engineer who was Master of Churchill College at the time, requesting his support in opening a new position for Paz at the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages. In his missive, he explained: “As the press has disclosed, Octavio Paz has broken with his government and resigned his Embassy over the shooting in Mexico City.” And as he stated further along, “Paz is, unquestionably, one of the three or four major figures en Latin American literature today, very possibly on a par with Neruda and Borges. It would be a brilliant feather in our cap if we could be his hosts.”

Sir William Hawthorne was quickly persuaded and communicated with the directors of all the departments or centers of research that might be interested in accommodating Paz. But none of them had any vacancies. John Street, Director of the Center of Latin American Studies, suggested an alternative: that he be put forward as a candidate to the Simón Bolívar Chair, created a year earlier at the behest of the Venezuelan government with the financial support of the Shell Oil Company in order to tighten cultural bonds between the United Kingdom and Latin America.

However, even those who were striving to employ Paz at the University were dubious as to the expediency of this option. The candidates for the Chair position had been selected by a committee composed of academics from Cambridge and the Ambassador from Venezuela in the United Kingdom. They feared that the Venezuelans would reject Paz’s candidacy under the argument of not wishing to offend the Mexican government by supporting someone who had openly opposed them, abandoning the embassy under his charge.

In order to weigh the gravity of the situation and to consider how they might overcome this obstacle, they consulted Sir John Walker, acting General Director of the Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Council, by virtue of his special insight into the Latin American intellectual and political panorama. Walker unequivocally replied that Paz was not merely an outstanding figure within contemporary Latin American culture, but perhaps the most important of them all. He believed that it was an extraordinary idea to bring him closer to England, given that his relations with Europe up until that time had been aligned with France.

Regarding the more delicate subject at hand, he warned that indeed, Paz had resigned the position of Ambassador to protest the “Mexican government’s repressive attitude towards university students.” He confessed that it was difficult for him to formulate an opinion regarding the attitude that might be taken by the Venezuelans with regards to Paz, although they “might possibly not wish to offend the Mexican government by pressing the candidature of one who stood up against them.” He concluded by suggesting that such musings were beyond the scope of the British members of the selection committee.

Everything seems to indicate that in the end, the question as to who would occupy the Chair was successfully decided without involving representatives of the Venezuelan government, Paz’s intellectual merits thus outweighing any potential diplomatic tensions between Mexico and Venezuela. By early December of 1968, Eric Ashby, the top administrative official at Cambridge University at the time, had confidentially, unofficially offered Paz the Simón Bolívar Chair for the 1969-1970 academic year. We know that Paz’s candidacy prevailed over that of other distinguished candidates: Victor Urquidi, also from Mexico; Pedro Grases, Humberto Fernández Morán, Ignacio Iribarren Borges, José Antonio Mayobre, Arturo Uslar Pietri and Marcel Roche, all from Venezuela; Ricardo Krebs, from Chile; Aldo Ferrer, from Argentina; and Sérgio Buarque de Holanda, from Brazil.

Paz accepted the invitation almost immediately, setting only one condition: instead of remaining in Cambridge during the entire academic year, that is to say, from October to September, he requested permission to do so from January to December of 1970. His petition was granted: his hosts showed themselves to be willing to adapt to any extraordinary circumstances.

The administrative documents I found make no mention of Paz’s activities during the year he spent in Cambridge. There are dozens of pages filled with administrative formalities that, in the end, contribute nothing of value. Only the Cambridge University Reporter, as a thorough record of scholarly events, confirms his presence and provides some new information: Paz gave two courses at the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages during three academic quarters. On Tuesdays, at eleven in the morning, he taught “Poesía moderna hispanoamericana: postmodernismo, vanguardia y tendencias contemporáneas” and on Wednesdays, from four to six in the afternoon, he led a seminar on Spanish and Spanish-American poetry. (5) In a conversation with the American journalist Rita Guibert, Paz observed that his students knew very little about Latin American literature and that an outmoded Iberian favoritism prevailed among them.(6) We do not know much more about these courses, although from their titles it is not hard to imagine that they would have come in handy for the development of his Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at the University of Harvard a few months later, eventually published as Children of the Mire: Modern Poetry from Romanticism to the Avant-garde.

After delving into the Cambridge files, I became convinced that, at least for now, the best approach to Paz’s residence in England remains The Monkey Grammarian, the enigmatic poem he wrote while living there. This book, as Paz himself suggested at some point, can be read as a farewell to India and the start of a voyage of self-discovery. In the end, this is what his period of voluntary exile in the arid academic world was all about: the gestation of a combative, polemicist Octavio Paz, intensely committed to the reality of his homeland. Someone for whom the classroom would turn out to be far too small.

1 “Tela de juicios.” Interview by Julio Scherer (September 30, 1993) Obras completas. Miscelánea III. Entrevistas. Mexico: Círculo de Lectores-Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003. p. 554.

2 “Soy otro, soy muchos…” Interview by Silvia Cherem S. Obras completas. Miscelánea III. Entrevistas. Mexico: Círculo de Lectores-Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003. p. 362.

3 “Soy otro, soy muchos…”. Interview with Silvia Cherem S. Obras completas. Miscelánea III. Entrevistas. Mexico: Círculo de Lectores-Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003. p. 363.

4 The documents are found at the Cambridge University Archives (GB730 Box882A File 1, GB730 Box883 File 2) and at the Churchill Archives Centre (CCPH/1/6/1-65, CCAC/110/2/3, CCAC/110/21 box 54).

5 Cambridge University Reporter No. 4703. 15 April 1971. Vol. C. No 30; Special 12, 15 April 1971. Vol. CI, p. 35.

6 “Octavio Paz”. Interview by Rita Guibert (4 October 1970): Obras completas. Miscelánea III. Entrevistas. Mexico: Círculo de Lectores-Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003. p. 476.

Luciano Concheiro studied History at the Autonomous National University of Mexico (UNAM) and Sociology at Cambridge University. He currently coordinates the Horizontal Center. His Twitter is @ConcheiroL

*Image by Rogelio Cuéllar

Al renunciar a su puesto como embajador en la India en protesta a la represión de estudiantes del 2 de octubre de 1968, Octavio Paz pasó un año en la Universidad de Cambridge. Hasta el momento, dicha etapa de su vida resulta prácticamente desconocida. En este breve ensayo, Luciano Concheiro ofrece nueva información sobre tal periodo contribuyendo a esclarecer ciertos aspectos de aquella histórica renuncia de Paz, la cual, sin duda, continúa desatando las más intensas polémicas.

Tras abandonar la embajada de la India en señal de protesta por la represión del 2 de octubre, Octavio Paz vivió, acompañado por Marie Jo, varios años en el autoexilio. Su histórica decisión causó natural descontento entre los adeptos al régimen y desencadenó de inmediato una acrimoniosa campaña en contra suya. Volver a México en aquel momento era, por decir lo menos, espinoso. Tiempo después, le explicaría a Julio Scherer:

“No creí que fuese cuerdo volver al país inmediatamente. Aparte de la hostilidad gubernamental, me habría visto envuelto en querellas estériles y circunstanciales, lo mismo con el poder público que con la oposición. Decidí esperar un poco: era claro que la represión no podía prolongarse y que pronto se abrirían espacios libres que harían posible la crítica y el debate”.(1)

Paz encontraría el refugio que necesitaba en tres universidades anglosajonas: Pittsburg, Texas (Austin) y Cambridge. En ellas se dedicaría a escribir, pero también a dar clases –práctica excepcional en su caso. Sería, como él mismo recalcaría en una entrevista tardía, su “primera y última experiencia universitaria”. (2)

La estancia en Cambridge terminaría siendo la más significativa de todas. No solamente fue la Universidad en la que permaneció más tiempo y en la última que residió antes de regresar a México en 1971, sino que ahí realizó el examen de conciencia que lo llevaría a decidir volver. En Cambridge, Paz se dio cuenta que tenía dos diálogos pendientes. El primero, con su madre: Josefina Lozano era mayor y quería acompañarla durante sus últimos años. El segundo, con su país: sentía que no podía abandonar a México en el momento crítico que vivía. Enclaustrado en la academia podría haber mantenido una vida cómoda y apacible, pero abandonar a su país le parecía una traición. En sus propias palabras: “Sí, en el extranjero habría podido escribir con más calma, pero abandonar a México en esas circunstancias hubiera sido, más que una evasión, una traición”. (3)

Hace poco tiempo, instigado por las tardes lluviosas y una conversación telefónica, decidí buscar rastros materiales del paso de Paz por Cambridge. Así descubrí, dispersos en un par de archivos, una serie de documentos relacionados con su estancia en esta Universidad.(4) Si bien, a excepción de un retrato y un par de postales, son esencialmente de índole administrativa, proporcionan información importante e iluminan varios elementos en torno a la figura de Paz durante esa época. Muestran, por un lado, el enorme prestigio que gozaba en el extranjero desde la década de los sesenta. Por otro lado, dan cuenta de la existencia de una eficaz red internacional de intelectuales constituida alrededor de él. Por último, prueban algo que resulta central para el recién resucitado debate sobre la renuncia de Paz a la Embajada en la India: la acción de Paz fue interpretada en el extranjero como una dura crítica al gobierno mexicano. Si se cambia la perspectiva de la discusión y, en lugar de centrarnos en las motivaciones e intenciones de Paz, analizamos los efectos de su decisión, resulta indiscutible que ésta fue una protesta histórica ante los hechos acaecidos el 2 de octubre en Tlatelolco.

Podemos suponer que Paz envió su carta de retiro y, de manera paralela, otras muchas pidiendo trabajo. Era 18 de octubre de 1968 y las cosas ya se estaban moviendo en Cambridge para encontrarle un puesto. Le había escrito al poeta Nathaniel Tarn expresándole su deseo de pasar algún tiempo en Inglaterra y preguntándole si alguna universidad lo podría emplear en temas de literatura hispánica o latinoamericana. Tarn, a su vez, informó a George Steiner del asunto. Fue él quien decidió interceder ante las autoridades de la Universidad de Cambridge.

Foto inédita de Octavio Paz en Cambridge. Ha sido publicada gracias al permiso de The Master and Fellows of Churchill College

Steiner procedió enviándole una carta a Sir William Hawthorne, afamado ingeniero y entonces Master del Churchill College, pidiéndole su apoyo para conseguir abrir un puesto en la Facultad de Letras Modernas para Paz. En su misiva, le explicaba que “tal y como la prensa ha revelado, Octavio Paz ha roto con su gobierno y renunciado a su Embajada debido a los tiroteos en la ciudad de México”. Más adelante, afirmaba: “Paz es, incuestionablemente, una de las tres o cuatro figuras más importantes de la literatura latinoamericana hoy en día, muy posiblemente a la par de Neruda y Borges. Sería un flamante logro si pudiésemos ser sus anfitriones”.

Sir William Hawthorne fue rápidamente persuadido y se comunicó con los directores de los departamentos o centros de investigación que pudieran estar interesados en acoger a Paz. En ninguno de ellos había vacantes. John Street, director del Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos, sugirió una alternativa: que se le propusiera como candidato a la Cátedra Simón Bolívar, la cual había sido creada un año atrás por gestiones del gobierno venezolano y con capital donado por la compañía petrolera Shell con el propósito de estrechar las relaciones culturales entre el Reino Unido y América Latina.

Sin embargo, aquellos que buscaban que Paz se estableciera en la Universidad dudaron de la conveniencia de esta opción. Los candidatos de la Cátedra era elegidos por un comité compuesto por académicos de Cambridge y el embajador de Venezuela en el Reino Unido. Temían que los venezolanos rechazaran su candidatura bajo el argumento de no querer ofender al gobierno mexicano apoyando a alguien que se había levantado en contra suya abiertamente al dejar la embajada que encabezaba.

Para sopesar la gravedad del asunto y ver cómo podían sortear esa dificultad, consultaron a Sir John Walker, quien fungía como director general del Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Council, y que por ende contaba con una visión privilegiada del ambiente intelectual y político latinoamericano. Walker contestaría contundentemente que Paz no era meramente una figura sobresaliente dentro de la cultura latinoamericana del momento, sino acaso la más importante de todas. Creía que era extraordinaria idea acercarlo a Inglaterra dado que sus relaciones con Europa hasta entonces habían estado alineadas con Francia.

Sobre el tema más delicado advertía que, efectivamente, Paz había renunciado al cargo de Embajador en protesta por la “actitud represiva del gobierno mexicano hacia los estudiantes universitarios”. Confesaba que le era difícil emitir una opinión sobre la actitud que podrían tener los venezolanos frente a Paz porque, aunque era posible que no quisieran “ofender al gobierno mexicano apoyando la candidatura de alguien que se había puesto en contra suya”, podían considerar que su posición intelectual “debería trascender consideraciones de este tipo”. Cerraba proponiendo que ésta fuera la visión de los británicos que estuvieran dentro del comité de selección.

Todo parece indicar que al final se logró que la decisión sobre quién ocuparía la Cátedra fuera tomada al margen de los representantes del gobierno venezolano y que los méritos intelectuales de Paz pesaran más que cualquier posible tensión diplomática que pudiese surgir entre México y Venezuela. A principios de diciembre de 1968, Eric Ashby, la máxima autoridad administrativa de la Universidad de Cambridge en el momento, le ofrecería a Paz de manera confidencial y no oficial la Cátedra Simón Bolívar para el año académico 1969-1970. Sabemos que la candidatura de Paz se impuso sobre la de otros distinguidos candidatos: el también mexicano Victor Urquidi; los venezolanos Pedro Grases, Humberto Fernández Morán, Ignacio Iribarren Borges, José Antonio Mayobre, Arturo Uslar Pietri y Marcel Roche; el chileno Ricardo Krebs; el argentino Aldo Ferrer; y el brasileño Sérgio Buarque de Holanda.

Paz aceptaría prácticamente de inmediato la Cátedra Simón Bolívar. Pondría tan sólo una condición: que, en lugar de permanecer en Cambridge durante el año académico, es decir, de octubre a septiembre, lo pudiera hacer de enero a diciembre de 1970. Su petición le fue concedida: querían ser sus anfitriones a toda cosa.

Los documentos administrativos que encontré guardan silencio sobre lo que hizo Paz durante el año que pasó en Cambridge. Hay decenas de folios repletos de formalismos administrativos que terminan no diciendo nada. Solamente el Cambridge University Reporter, publicación en la cual se registran obsesivamente los sucesos de la Universidad, constata su presencia y proporciona nueva información: dio un par de cursos en la Facultad de Lenguas Modernas y Medievales durante tres trimestres. Los martes, a las once de la mañana, impartía “Poesía moderna hispanoamericana: postmodernismo, vanguardia y tendencias contemporáneas” y los miércoles, de cuatro a seis de la tarde, dirigía un seminario sobre poesía española e hispanoamericana.(5) En una conversación que tuvo lugar entonces, Paz comentó que sus alumnos sabían poco de literatura latinoamericana y que existía entre ellos un españolismo trasnochado. (6) No sabemos mucho más de esos cursos, aunque por sus títulos es fácil suponer que en ellos empezó a desarrollar lo que unos meses después expondría en sus Charles Eliot Norton Lectures de la Universidad de Harvard y que luego se publicarían como Los hijos del limo: del romanticismo a la vanguardia.

Tras la inmersión en los archivos de Cambridge, me convencí de que, al menos por ahora, la mejor fuente para acercarse al tiempo de Paz en Inglaterra sigue siendo El mono gramático, el enigmático poema que escribió mientras vivía ahí. Este libro, como sugirió Paz en algún lugar, puede ser leído como su despedida de la India y el inicio de un recorrido al encuentro de sí mismo. En el fondo, de eso trató su periodo de autoexilio en el árido mundo académico: un encuentro con el Octavio Paz combativo y polemista, el intensamente comprometido con la realidad de su país y al cual el salón de clases le quedaba chico.

1 “Tela de juicios” Entrevista con Julio Scherer (30 de septiembre de 1993) Obras completas. Miscelánea III. Entrevistas. México: Círculo de Lectores-Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003. p. 554.

2 “Soy otro, soy muchos…”. Entrevista con Silvia Cherem S. Obras completas. Miscelánea III. Entrevistas. México: Círculo de Lectores-Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003. p. 362.

3 “Soy otro, soy muchos…”. Entrevista con Silvia Cherem S. Obras completas. Miscelánea III. Entrevistas. México: Círculo de Lectores-Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003. p. 363.

4 Los documentos se encuentran en los Cambridge University Archives (GB730 Box882A File 1, GB730 Box883 File 2) y en The Churchill Archives Centre (CCPH/1/6/1-65, CCAC/110/2/3, CCAC/110/21 box 54).

5 Cambridge University Reporter No. 4703. 15 abril 1971. Vol. C. No 30; Special 12, 15 abril 1971. Vol. CI, p. 35.

6 “Octavio Paz”. Entrevista de Rita Guibert (4 de octubre de 1970): Obras completas. Miscelánea III. Entrevistas. México: Círculo de Lectores-Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003. p. 476

Luciano Concheiro estudió historia en la UNAM y sociología en la Universidad de Cambridge. Es coordinador del Centro Horizontal y profesor de asignatura en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la UNAM. Su Twitter es: @ConcheiroL

Luciano Concheiro estudió historia en la UNAM y sociología en la Universidad de Cambridge. Es coordinador del Centro Horizontal y profesor de asignatura en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la UNAM. Su Twitter es: @ConcheiroL

*Imagen de Rogelio Cuéllar