Gabriel Orozco: The Poetry of Forms

Evan J. Garza

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

A master of diverse media and subject matters, Orozco has created a substantial body of work that, at each stage of his career, leaves absolutely no detail with which to predict his impending projects.

The phrase, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”, suggests that discovering splendor is an altogether subjective experience. And if that’s the case, it’s not the thing that is beautiful, but instead the relationship to the object is what remains gorgeous. This theory resounds through much of Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco’s work, in each of his many mediums—as if dangling the fantastic nature of the everyday in front of us like tiny handmade stars hung by strings.

His work includes sculpture, installation, video, drawing, painting, and photography—investigating issues as diverse and numbered as the mediums in which they are made. His sculptural and photographic work often feature found or industrially fabricated objects, like a deflated soccer ball filled with water, a reassembled Citroën automobile, and misplaced items at a grocery store. He highlights meaning in the mundane and frequently transforms the ordinary, often through incredibly simple gestures or a title, adding layers of depth where once there may have been none.

Orozco is one of the most important contemporary artists working in Mexico today, and the evidence to support this case is staggering. Born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico in 1962, the artist now lives and works in New York, Paris, and Mexico City. El Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City recently hosted the most comprehensive survey of the artist’s work to date. He’s been featured in the Whitney Biennial twice, participated in the Venice Biennale three times, and has enjoyed solo exhibitions at some of the finest museums in the world.

He has influenced a number of the world’s most significant contemporary artists, including Mexican art star Gabriel Kuri, who was active in Orozco’s studio for a large part of the late 80s and early 90s. Kuri’s attention to post-minimalism, conceptualism, and found objects were undoubtedly influenced during this period. While Kuri’s work is more focused on man’s relationship to materialism, the fundamental roots of this investigation lie in the study of objects, a key element of Orozco’s work. His influence on many others has practically spawned a new generation of contemporary artists, the bulk of which in Latin America and France, using similar conceptual relationships to the readymade and everyday objects.

Orozco’s sculptures are as varied as the mediums with which he uses to create them. One of his primary focuses has been game-based sculpture, often taking traditional gaming activities and layering them with various conceptual undertones. For Oval With Pendulum (1996), an oval-shaped billiard table sans pockets was made to the artist’s specifications, and is displayed with two white cue balls on the green felt surface and a third red ball swinging above from a pendulum. The circle or oval shape is a recurring image in the artist’s varied oeuvre and here the curvaceous form of the table is in severe contrast to the sharp angles of its traditional counterpart. A witty homage to Man Ray’s 1938 painting “La Fortune”, Oval With Pendulum possibly highlights the idiocy of competition, but more likely examines the foundation of gaming itself. In reality, not all rules are followed and some rules are bent completely – not unlike the curvilinear shape of Orozco’s table.

Ping Pond Table (1998) is another example of the artist’s conceptual take on games. Instead of a rectangular, double-sided playing field, the artist opened the table to four sides, each with rounded edges, and placed a lily pond in the center where the net should be. Here, the focus is less about the role of competition but instead about constraint. Orozco has created an in-between space that didn’t exist previously, and filled it with meaning completely foreign to the game of ping pong. That in-between space, like the subjective relationship one finds to beauty, consistently saturates much of the artist’s conceptual thought in his sculptural investigations. Instead of being confined by a net (or a single opponent), the viewer is free to use their imagination and associate that space with subjective matter.

In Orozco’s recent paintings, his curiosity with the circular form has led to philosophical studies of its structure, not only as an organic form, but also as a geometric one. The images in his Samurai Tree paintings (2005-06) are ornately scattered quarter, half, and full circles in luscious egg tempera reds and blues with gold leaf, constructed according to rules of size and color, and based on the properties of moving chess pieces. The multicolored circles appear to swirl outward, as if propelled from a vaguely formed vortex, shifting in size. The three-dimensional movement on a two-dimensional field mimics the L-shaped movements of a knight on a chessboard, adding a seemingly tangible depth to a plane that should feel flat.

His work recounts genuine narratives of the oft-ignored splendor of the things we take for granted, and creates space in the places we were most certain it could not exist. —EVAN J. GARZA

It is Orozco’s installations, however, that are truly poetic- not only in their beauty and grandeur, but in the rich context of their conceptual motivations. His enigmatic 1993 piece, La DS (pronounced “la déesse”, French for ‘goddess’), is a reconfi gured Citroën DS vehicle that beautifully offsets the iconic nature of sleek automobiles with the threat of incapability through an optical distortion that is as visually stunning as it is incongruous. The vehicle was trisected into roughly equal sections, with the middle piece removed entirely, and the two lateral sides then carefully sutured together, leaving an end result that appears unchanged from the sides and strangely deformed when seen from any other angle. Every newly fabricated piece of vehicle, every pane of glass, and each stitch of leather appear as if the DS were originally constructed this way; unmodifi ed from its original design. It’s a marvel of craftsmanship and one of the artist’s most obvious attempts in bringing forth his signature brand of imagination and eccentricity, leaving the viewer with a tangible sense of both chaos and order, harmony and dissent, attraction and repulsion.

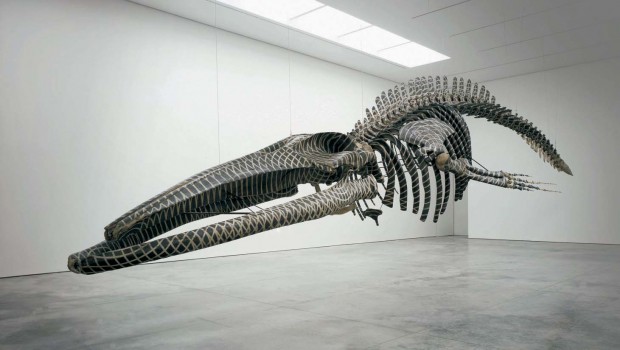

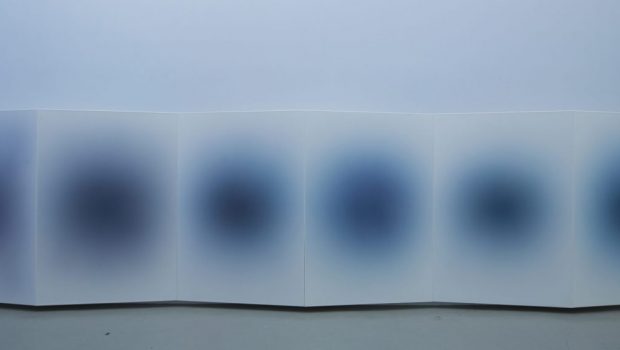

One of the artist’s latest sculptural installations, Dark Wave (2006), recently on view at Jay Jopling’s new White Cube gallery space at Mason’s Yard in London, marries Orozco’s fascination with the organic nature of circles with massive scale. The bones of a 46-foot fin whale were collected from the southwest coast of Spain and assembled by a team of 20 people for three months. Later, the bones were cast in non-perishable calcium and covered in hand-drawn concentric circles, stemming from disparate points on the whale’s body: the eye sockets, the tip of its mouth, and the sternum. When looking at the circles from nearly every point of the beast, the rings appear like ripples on the surface of water or sound waves reverberating through the giant frame, bouncing against other lines and creating an intricate and organic pattern of lightly-colored bands on the dark, dead bones. It’s yet another incarnation of Orozco’s majestic nature, and his near effortless ability to breathe life into objects that are all but stripped of it.

A master of diverse media and subject matter, Orozco has created a substantial body of work that, at each stage of his career, leaves absolutely no detail with which to predict his impending projects. Any attempt to do so is one made in futility. His work demonstrates contemporary art’s post-medium climate where attempts to use varied and disparate mediums abandon the Modernist compulsion of medium-specificity. His work recounts genuine narratives of the oft-ignored splendor of the things we take for granted, and creates space in the places we were most certain it could not exist. Through a series of fluid gestures that traverse the physical, conceptual, and cultural facets of his subjects, he creates novel manifestations of things we know as if we are seeing them for the very first time.

About the Artist

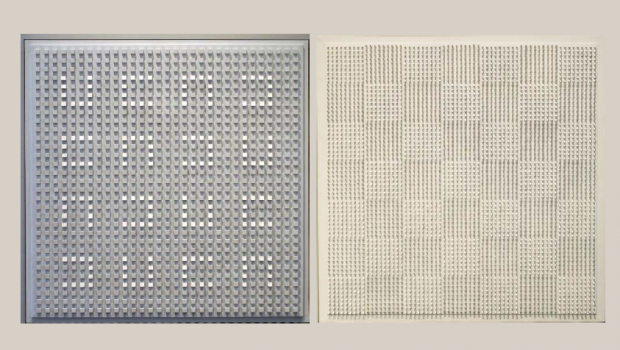

Gabriel Orozco was born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico in 1962 and studied at the Escuela Nacional de Arte Plasticas in Mexico City, and at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, Spain. He uses the urban landscape and the everyday objects found within it to twist conventional notions of reality and engage the imagination of the viewer. Orozco’s interest in complex geometry and mapping find expression in works like the patterned human skull of Black Kites, the curvilinear logic of Oval Billiard Table, and the extended playing field of the chessboard in Horses Running Endlessly. He considers philosophical problems, such as the concept of infinity, and evokes them in humble moments, as in the photograph Pinched Ball, which depicts a deflated soccer ball filled with water. Matching his passion for political engagement with the poetry of chance encounters, Orozco’s photographs, sculptures, and installations propose a distinctive model for the ways in which artists can affect the world with their work. Orozco was featured at Documenta XI (2002), where his sensuous terra-cotta works explored the elegance and logic of traditional ceramics—a pointed commentary on Mexican craft and its place in a ‘high art’ gallery space. Orozco has shown his work at distinguished venues including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Venice Biennale. Gabriel Orozco lives and works in New York, Paris, and Mexico City.

Posted: April 13, 2012 at 9:29 pm