A Journey to the Primal House: A Conversation with Isaac Goldemberg

Viaje a la primera casa

Benito Pastoriza Iyodo

Translated to English by Sharon Kerr and Marisela Chaplin

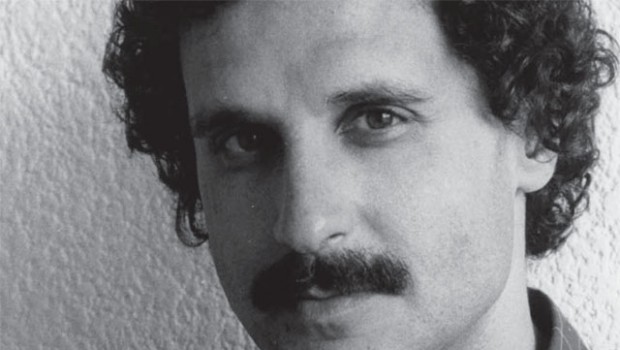

Isaac Goldemberg was born in Peru in 1945 and has lived in New York since 1964. He has published three novels, eleven books of poetry, three plays and an anthology. His work has been translated to several languages. In 2001, his novel La Vida a Plazos de Don Jacobo Lerner was selected as one of the 100 most important works of Jewish literature in the past 150 years. He is a distinguish professor at the Hostos Community College (CUNY), where he is also the director of the Institute of Latin American Writers and the Hostos Review.

* * *

BENITO PASTORIZA IYODO: Upon reading your poetic works, the reader has the sensation that s/he is about to embark on a great journey. Where does this journey go?

ISAAC GOLDEMBERG: It goes to the origins, to the primal house, to the individual and collective unconscious, to that point where the self, if it were to arrive, would be able to perceive the very act of Creation, Creation with a capital C. It’s a journey drawn by the desire that every human being has to find him or herself fulfilled. It is also a journey projected toward the future, constantly returning.

B. P. I.: In your poetry collections, there seems to be a conversation with the past. What are you trying to reclaim from that past?

I. G.: My intent is to reclaim a personal and collective history. If, in my poems and narratives, I continue to refer to a familiar and common past, it’s because what interests me about my past and the past in general, is to reclaim my identity as an individual and as a historical being. So in both my poetry and narrative I constantly turn to myth, often trying to achieve a synthesis of the Peruvian and Jewish myths. At this level, it could be said that my work is the rewriting of an experience which is both historical and mythical: the Jewish exile. The first exile refers to, of course, the banishment from paradise: those origins, that primal house that we talked about a while ago. What comes out of my work is the desire to deeply experience the Jewish exile, not only as a historical occurrence but also as a mythical event. In referring constantly to the past, especially in my poems, what I try to do is reclaim a series of myths still present but dormant in Judaism. And, to explore that other part of myself, I try to do the same with the Peruvian myths. That is to say, looking at history not as a mere succession of events but as a collection of facts that unfold from a shared cosmological cosmovision. That’s why my novels or my poems shouldn’t be taken as an autobiography, nor as a true history of the Jewish Peruvian community, nor about a particular provincial life in Peru. All of that only serves as background to present an experience in which the historical participates once more in certain mythical memories.

B. P. I.: Your poetry seems to flow over into the pages of your novels. The same thing happens in your poetry collections where poetry almost becomes prose or an extension of your novels. How do you explain this duality?

I. G.: One time, in another interview, I said that when I write poetry I feel like a poet and when I write novels I feel like a novelist, but the truth is that it’s always been impossible for me to create a clear and emphatic split between the poet and the novelist. In reality, the duality you’re talking about happens like a controlled schizophrenia, controlled in the sense that at every moment the poet must be aware that he is fabricating a poem and not a story: not even a poem in prose. The same thing happens with the narrative: the writer must be fully aware that he’s fabricating a tale or a novel. I prefer the term fabricate to write because the poem, the story and the novel are artistic objects that have very particular demands, demands which at the same time demand to be transgressed if the purpose is to create a work of art – that is to say an object that responds to a particular and unique vision of the world – and not only to repeat a pre-established model. Human beings react to reality, to a vital situation, by making art and I think that the aim of all art – writing included – is to provide a certain idea of the world, but an idea that cannot be repeated, his/her own. And the artist makes art, or tries to make it, through transgression. That’s why, in my poetry, my transgressor self is the novelist and in my novels my transgressor self is the poet.

B. P. I.: Your verses have a phantasmagoric feeling that reminds us of Ramón López Velarde and César Vallejo. Is this a different direction or is there an implicit poetic intertextuality here?

I. G.: Well, I hadn’t really thought about it before, but there is something in my poetry that is reminiscent of López Velarde, but only by coincidence and the fact that we have both worked with elements that belong to the countryside, the Peruvian and Mexican countryside. The phantasmagorical is a natural part of López Velarde’s poetic environment because the Mexican countryside is naturally like that. I remember that in his poetry there are flying gloves, skeletons dancing through the universe, etc. You can also note a Rulfian element in his poems and this is what, in some way, makes us alike. With Vallejo it’s different: here there is an implicit poetic intertextuality. At an unconscious or conscious level, I have an ongoing dialogue with Vallejo, especially in those poems that have to do with my condition as a mestizo. Yes, there is a lot of the phantasmagorical in Vallejo’s poetry, poems where, for example, the narrator returns to his house and no one in his family exists anymore, only the echo of what was and no longer is. I’ve also worked with these elements, with a past populated by ghosts – parents, children – as I say, precisely, in a poem, if my memory is correct, titled “Crónicas”. But besides the phantasmagorical, my intertextual dialogue with Vallejo is fanned by another bellows: that of the telluric force, which comes from feeling that I am the product of a cultural and racialmestizaje. So I’ve also created narrators who show, for example, a religious thirst like the biblical prophets, or I’ve written poems where the numeric symbolism has priority, or where I try to express the thoughts and feelings of mymestiza race. But, as opposed to Vallejo, almost always with a good dose of irony. Rather, of nostalgia and irony. Although, now that I think about it, Vallejo can also be ironic as well as nostalgic. But my irony is not his: irony comes to me from the channels of culture and Jewish literature.

B. P. I.: Does your poetry offer a theology of a common God forgotten by man?

I. G.: More than forgotten, a reconfigured God. And yes, also a common God; common in its sense of a current ordinary entity – in the best sense of the word – as much as not being anyone’s private property. Many of my poems make reference to God; in others God plays a leading role, not with the purpose of grasping His divine essence, but rather questioning the role He has played as an active agent – an agent created by human beings – within the history of humanity in general and the history of the Jewish people in particular. In this way, God appears as a type of “common” being, as a historical character who has had an important role among the Jewish people since the Genesis and, as such, becomes an extension of the consciousness of those people.

B. P. I.: Is there a battle against forgetting in your work?

I. G.: Of course, of not forgetting the past: that’s the watchword. The collective memory sustains my identity. It is through memory that I can register myself in the flow of history: I am, therefore I remember where I come from and where I’m going. Memory is that shelter where I can reorganize and give new meaning to the past. For me, to remember is to re-create. It’s not merely returning to the past but adapting the past to present circumstances.

B. P. I.: Why do you return to poetry in an environment where poetry has lost prestige to the novel?

I. G.: Well, I don’t believe that good poetry has lost prestige. What happens is that there’s a lot of bad poetry now and this makes poetry in general less popular and less prestigious than the novel. Of course, there are also bad novels, completely hollow, that say little or nothing. Many people read them, true, but this doesn’t mean that these novels deserve any prestige. You ask why I return to poetry and, as I’ve never left it, I suppose you’re referring to why I write it. It’s not a voluntary thing. It’s something that imposes itself in a natural way without my knowing. I see, I hear anything and suddenly images and words start to come up which immediately – without meaning to and as if by magic – take the shape of a poem. Of course, inspiration is not all of it: then comes the work of fabricating the poem.

B. P. I.: What’s your opinion of poetry produced by Latinos in the United States?

I. G.: In the first place, it’s a poetry with multiple and heterogeneous tendencies. It’s a phenomenon so rich in its manifestations that you can’t talk about one particular style, nor one particular theme. Each nationality, each ethnic group, has a considerable number of valuable poets, poets who are producing an important body of work not only in terms of what they’re producing on this side of the river but in their own countries as well. If we were to mention names – which I won’t do because there are many and you always run the risk of leaving somebody out – the list would be endless. There are poets of all nationalities, and more appear every day; poets that write on a wide variety of subjects in Spanish, in English, in both languages or in that hybrid creature called Spanglish. Not everything that’s written is good, of course, but as a whole there’s a high level of quality. What’s important is that the poetic dialogue between the poets from here and from there, as well as between poets living in the United States, continue to be constant and fruitful.

B. P. I.: Could the United States be regarded as the new Hispanic homeland for many Latinos who come to blend their cultures and idiosyncrasies in this country?

I. G.: Yes, in a certain way. Blending our cultures and idiosyncrasies in the so-called and historical “melting pot” seems accurate to me, but we should be able to accomplish this without it meaning that we incinerate our differences. I think that the watchword should be the following: to be equal to others and, at the same time, different. I think that the new Hispanic Homeland in the United States should be built on a background of the comings and goings of our identity and the new “American identity”, with our own language and the new language, with our own history and the history of the United States; a homeland where Latinos can see our own Latin identity reflected and where “Americans” who aren’t Latinos can see their “Americanism” reflected, but in a mirror that offers the image, not of a one dimensional “Americanism”, but of a multifaceted one.

B. P. I.: Could a Hispanic literature representing a multifaceted reality come out of the United States?

I. G.: I think that Latino literature in the U.S. is following a similar course to that of Jewish literature in Latin America. In the same way, Latino literature has already developed a “Latino” “American” discourse in the United States. Latino literature, as a writing with the marginal status of a minority discourse – like the literature of other ethnic groups – serves an important function as the counterpoint to the official discourse. In this sense, Latino literature offers a challenge to the canon established as the “authentic voice” of the United States. That is to say, a literature that questions the process by which the accepted truths have been established. Therefore, the Latino point of view is not divorced from the social environment; rather it offers the possibility of a dialogue-discourse of change. Another odd phenomenon in this process is that the Latino population in the U.S. is so vast, especially in cities like New York, Miami, Chicago and Los Angeles, that writers no longer feel that they’re living “totally” in exile, as happened in the past with writers who moved to Europe, for example. This gives Latino writers the chance to explore more freely, and from a different point of view, issues such as what it means to be Latino and “American”. That is to say, explore the hereditary identity and the new “American identity” at the same time, fruit of the mestizaje of the two Americas and of two or more languages. And to that end they make use of Spanish and Spanglish, and even standard English, and English made impure not only by the infusion of Castilian words and phrases, but also by the changes in syntax that a language is subject to when those who speak it have another way of thinking and seeing the world. Because of all of this, and to get back to your question, I do think that a literature particular to Latinos already exists and that it represents a more multifaceted reality. I think that Latinos in general, and writers in particular, are building a collective homeland of the spoken word, knowing that to build a collective homeland of the spoken word implies stepping back – and/or building bridges – between the old and the new, between the lands of banishment and the new promised land. And they know that for this a language has to be built, a language – it could be Castilian, English or Spanglish – that expresses the collective experience of Latinos in the USA, a language that serves as a mirror to see themselves and to see the other, a language that is the reflection of the determination of the Latino community of this country to interpret itself. Latino writers know that the subject of ethnic identity, instead of becoming outdated, remains current for the cultural, social and political life of the United States. That’s why a large number of them are writing about issues related to their origins, their culture and their language. And it’s precisely this quest, undertaken from a multicultural and multilingual perspective, which keeps driving them to design a Latino reality that is multifaceted and not monolithic.

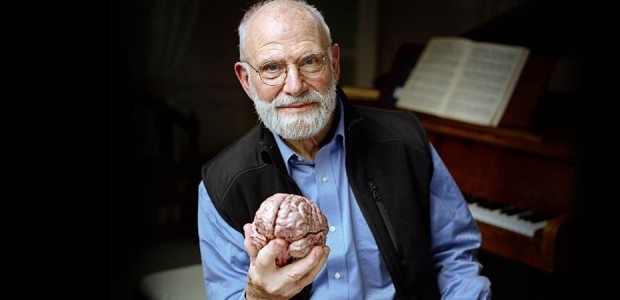

-The Societé des Poetes Francais, an ancient organization that has welcomed the most important poets of the world, recently invited Isaac Goldemberg to read his poems.

Isaac Goldemberg nació en Perú en 1945 y reside en Nueva York desde 1964. Ha publicado tres novelas, once libros de poesía, tres obras de teatro y una antología. Su obra ha sido traducida a varios idiomas. En el 2001 su novela La vida a plazos de don Jacobo Lerner fue seleccionada como una de las 100 obras más importantes de la literatura judía mundial de los últimos 150 años. Actualmente es Profesor Distinguido de Hostos Community College (CUNY), donde también dirige el Instituto de Escritores Latinoamericanos y la Hostos Review.

* * *

BENITO PASTORIZA IYODO: Al leer su obra poética, el lector lleva la sensación de que la misma embarca al individuo por un gran viaje. ¿Hacia dónde va ese viaje?

ISAAC GOLDEMBERG: Va hacia los orígenes, hacia la primera casa, hacia el inconsciente individual y el colectivo. A ese punto donde el ser, si llegara, sería capaz de presenciar el acto mismo de la Creación, de la Creación con mayúscula. Es un viaje jalado por el deseo que tiene todo ser humano por reencontrarse consigo mismo en plenitud. Un viaje proyectado también hacia los futuros, en un eterno retorno.

B. P. I.: En sus poemarios parece haber una conversación con el pasado. ¿Qué se intenta rescatar de ese pasado?

I. G.: Intento rescatar una historia personal y colectiva. Si en mis poemas y en mi narrativa, no cejo de referirme a un pasado familiar y comunitario, es porque lo que me interesa de mi pasado y del pasado en general, es rescatar mi identidad como individuo y como ser histórico. Por eso es que tanto en mi poesía como en mi narrativa recurro constantemente al mito, intentando menudo lograr una síntesis entre los mitos peruanos y los judíos. En este nivel, podría decir que mi obra es la reactualización de una vivencia que es al mismo tiempo histórica y mítica: el exilio judío. El primer exilio se refiere, por supuesto, a la expulsión del paraíso: esos orígenes, esa primera casa de la que hablábamos hace un rato. Lo que se da en mi obra es el deseo de experimentar profundamente el exilio judío, no sólo como acontecimiento histórico sino también como un suceso mítico. Al referirme constantemente al pasado, sobre todo en mis poemas, lo que intento es recuperar una serie de mitos todavía latentes en el judaísmo. Y trato de hacer lo mismo al ocuparme de los mitos peruanos para explorar esa otra parte de mi ser. Es decir, viendo la historia no como una mera sucesión de eventos sino como un conjunto de hechos que se despliegan a partir de una cosmovisión cosmológica compartida. Por eso mis novelas o mis poemas no deben tomarse como una autobiografía, ni como una historia real de la comunidad judía peruana, ni de cierta vida provinciana en el Perú. Todo eso sólo sirve de telón de fondo para presentar una experiencia en la cual lo histórico vuelve a participar de ciertas memorias míticas.

B. P. I.: Su poesía parece extenderse en las páginas de sus novelas. El mismo acto ocurre en sus poemarios donde la poesía casi se vuelve prosa o una extensión de sus novelas. ¿Cómo se entiende esa dualidad?

I. G.: Una vez, en otra entrevista, dije que cuando escribo poesía me siento poeta y que cuando escribo novela me siento novelista, pero la verdad es que siempre me ha resultado imposible crear una ruptura clara y tajante entre el poeta y el novelista. En realidad esa dualidad de la que hablas se da como una suerte de esquizofrenia controlada, controlada en el sentido de que en todo momento el poeta debe estar consciente de que está fabricando un poema y no un relato: ni siquiera un poema en prosa. Lo mismo ocurre con la narrativa: el narrador debe estar plenamente consciente de que está fabricando un relato o una novela. Prefiero el término fabricar a escribir porque el poema, el relato y la novela son objetos artísticos que tienen exigencias muy propias, exigencias que a su vez exigen ser transgredidas si el propósito es crear una obra de arte —es decir un objeto que responda a una visión particular y única del mundo— y no sólo repetir un modelo preestablecido. El ser humano reacciona ante la realidad, ante una situación vital haciendo arte y pienso que la finalidad de todo arte —incluida la escritura— es proporcionar una cierta idea del mundo, pero una idea irrepetible, propia. Y el arte se logra, o se intenta lograr, mediante la transgresión. Por eso en poesía mi yo transgresor es el novelista y en novela mi yo transgresor es el poeta.

B. P. I.: En sus versos hay una sensación fantasmagórica que recuerda a Ramón López Velarde y César Vallejo. ¿El trayecto es distinto o hay una intertextualidad poética implícita aquí?

I. G.: Bueno, no lo había pensado antes, pero sí hay algo en mi poesía que recuerda a López Velarde, pero sólo por coincidencia, por el hecho de que ambos hemos trabajado con elementos que son propios de la provincia, de la peruana y de la mexicana. Lo fantasmagórico es parte natural del ámbito poético de López Velarde porque la provincia mexicana es así de manera natural. Recuerdo que en su poesía hay guantes que vuelan, esqueletos bailando por el universo, etc. Incluso, puede notarse un elemento rulfiano en sus poemas y esto es lo que de algún modo nos emparenta. Con Vallejo es distinto: ahí sí hay una intertextualidad poética implícita. A nivel inconsciente o consciente, yo tengo un diálogo perenne con Vallejo, sobre todo en aquellos poemas que tienen que ver con mi condición de mestizo. Sí, hay bastante de fantasmagórico en la poesía de Vallejo, poemas donde por ejemplo el hablante lírico regresa a su casa y ya no existe nadie de su familia, sólo el eco de lo que fue y ya no es más. También yo he trabajado con estos elementos, con un pasado poblado por fantasmas, que son padres, que son hijos, tal y como digo, precisamente, en un poema, que si mal no recuerdo, se titula “Crónicas”. Pero además de lo fantasmagórico, mi diálogo intertextual con Vallejo está insuflado por otro fuelle: el de la fuerza telúrica, por sentirme fruto de un mestizaje cultural y sanguíneo. Entonces, también yo he creado hablantes líricos que muestran por ejemplo una sed religiosa a modo de los profetas bíblicos, o he escrito poemas donde prima el simbolismo numérico, o donde intento expresar el sentir y el pensar de mi raza mestiza. Pero, a diferencia de Vallejo, casi siempre con su buena dosis de ironía. Más bien de nostalgia e ironía. Aunque, bien pensado, también Vallejo, además de nostálgico, podía ser irónico. Pero mi ironía no es vallejiana: a mí la ironía me llega por los cauces de la cultura y la literatura judía.

B. P. I.: ¿Se propone en su poesía una teología de un Dios común olvidado por el hombre?

I. G.: Más que olvidado, de un Dios reconfigurado. Y sí, de un Dios común también, tanto en su calidad de entidad ordinaria, corriente —en el mejor sentido de la palabra— como en el no ser propiedad particular de ninguno. En muchos de mis poemas se hace referencia a Dios, en otros Dios ocupa un papel protagónico, pero nunca con el propósito de conocer su esencia divina, sino para cuestionar el papel que ha desempeñado como agente activo —agente creado por los seres humanos— dentro de la historia de la humanidad en general y de la historia del pueblo judío en particular. De este modo, Dios aparece como una especie de ser “común”, de personaje histórico que desde el Génesis ha tenido un papel importante en la historia del pueblo judío y que, como tal, pasa a convertirse en extensión de la conciencia de dicho pueblo.

B. P. I.: ¿Existe una batalla contra el olvido en su obra?

I. G.: Claro, no olvidar el pasado: ésa es la consigna. Mi identidad se sostiene en la memoria colectiva. Es a través de la memoria que puedo inscribirme en el flujo histórico: soy, en tanto recuerdo de dónde vengo y adónde voy. La memoria es ese reducto donde logro reorganizar y dar un nuevo significado al pasado. Para mí recordar es re-crear. No es un mero regreso al pasado sino la adaptación del pasado a las circunstancias del presente.

B. P. I.: ¿Por qué regresa a la poesía en un ámbito donde ésta parece haber perdido prestigio ante la novela?

I. G.: Bueno, no creo que la buena poesía haya perdido prestigio. Lo que pasa es que ahora existe mucha poesía mala y eso hace que la poesía en general sea menos popular y que esté menos prestigiada que la novela. Claro, también existen novelas malas, absolutamente huecas, que dicen nada o muy poco. Mucha gente las lee, es cierto, pero esto no quiere decir que estas novelas gocen de prestigio. Me preguntas por qué regreso a la poesía y, como nunca la he dejado, supongo que te refieres a por qué la escribo. No es algo voluntario. Es algo que se me impone de manera natural sin que yo sepa cómo. Veo, escucho cualquier cosa y de repente empiezan a surgir imágenes y palabras que inmediatamente —sin proponérmelo y como por arte de magia— adquieren forma de poema. Claro que en esto no todo es inspiración: luego viene el trabajo de fabricación del poema.

B. P. I.: ¿Cómo ve usted la poesía producida por los latinos en Estados Unidos?

I. G.: En primer lugar, se trata de una poesía de tendencias múltiples y heterogéneas. Constituye un fenómeno tan rico en manifestaciones que no se puede hablar de una sola corriente estilística , ni de una sola temática. Cada nacionalidad, cada grupo étnico cuenta con un número considerable de poetas valiosos, de poetas que están haciendo una obra importante no sólo en términos de lo que se produce desde esta orilla sino en sus propios países. Si nos pusiésemos a mencionar nombres —cosa que no haré porque son muy numerosos y porque siempre se corre el riesgo de olvidar alguno — la lista sería interminable: hay poetas de todas las nacionalidades, y cada día aparecen más; poetas que escriben acerca de una gran variedad de temas en español, en inglés, en ambos idiomas o en esa criatura híbrida llamada espanglish. No todo lo que se escribe es bueno, por supuesto, pero en su conjunto el nivel es de mucha calidad. Lo importante es que el diálogo poético entre los poetas de aquí y los de allá, así como entre los poetas que viven en Estados Unidos, siga siendo constante y fructífero.

B. P. I.: ¿Se podría ver Estados Unidos como la nueva patria hispánica para muchos latinos que vienen a fundir sus culturas e idiosincrasias en este país?

I. G.: Sí, en cierto modo sí. Lo de fundir nuestras culturas e idiosincrasias en el tan mentado e histórico “crisol de razas” me parece acertado, pero eso habríamos que lograrlo sin que signifique la incineración de nuestras diferencias. Pienso que la consigna debe ser la siguiente: ser iguales a los demás y ser, a la vez, diferentes. Pienso que sobre este telón de fondo, de idas y venidas con nuestra identidad y la nueva American identity, con el propio idioma y el nuevo idioma, con la propia historia y la historia de Estados Unidos, debe ir haciéndose esa nueva patria hispánica en los Estados Unidos. Una patria donde los latinos podamos ver reflejada nuestra propia latinidad y donde los “americanos” no latinos puedan ver reflejada su “americanidad”, pero en un espejo que les ofrezca la imagen de una “americanidad” no unidimensional, sino multifacética.

B. P. I.: ¿Podría surgir de Estados Unidos una literatura ya propia de los hispanos que represente una realidad multifacética más completa de lo que somos?

I. G.: Pienso que la literatura latina en Estados Unidos está siguiendo un derrotero parecido al de la literatura judía en América Latina. Al igual que ésta, la literatura latina ya ha desarrollado un discurso “latino” “americano” en Estados Unidos. Como escritura con estatus marginal de discurso minoritario, la literatura latina —al igual que la literatura de otros grupos étnicos—, cumple una función importante como contravoz del discurso oficial. En este sentido, la literatura latina ofrece un desafío al canon establecido como la “voz auténtica” de Estados Unidos. Es decir, se trata de una literatura que cuestiona el proceso por el cual las verdades aceptadas se han establecido de esa manera. Así, el punto de vista latino no aparece divorciado del medio ambiente social, sino que proporciona la posibilidad de un discurso diálogico de la alteridad. Otro fenómeno curioso de este proceso es que la población latina de Estados Unidos es tan vasta, especialmente en ciudades como Nueva York, Miami, Chicago o Los Angeles, que los escritores ya no sienten que están viviendo “totalmente” en el exilio, como ocurrió en épocas anteriores con los escritores que se radicaron en Europa, por ejemplo. Esto hace que los escritores latinos puedan explorar con más libertad y desde nuevas perspectivas cuestiones como qué significa ser latino y “americano”. Es decir, explorar al mismo tiempo la identidad heredada y la nueva American identity, fruto del mestizaje de dos Américas y de dos o más idiomas. Y para ello se valen del español y del espanglish, e incluso del inglés estandard, un inglés hecho impuro no sólo por la infusión de palabras y frases castellanas, sino por los cambios sintácticos que recibe una lengua cuando quienes la hablan tienen otra manera de pensar y ver el mundo. Por todo esto y para volver a tu pregunta, sí pienso que existe ya una literatura propia de los latinos y que ésta representa una realidad más multifacética. Pienso que los latinos en general, y los escritores en particular, están fundando una patria colectiva del habla, a sabiendas de que fundar una patria colectiva del habla implica poner distancia —y/o tender puentes— entre lo viejo y lo nuevo, entre las tierras de expulsión y la nueva tierra prometida. Y saben que para esto hay que fundar un idioma, un idioma —puede ser el castellano, el inglés o el espanglish— que exprese la experiencia colectiva de los latinos en USA. Un idioma que les sirva de espejo para verse ellos mismos y para ver al otro. Un idioma que sea un reflejo del esfuerzo de autointerpretación en que se halla empeñada la comunidad latina de este país. Los escritores latinos saben que el tema de la identidad étnica, en vez de convertirse en un tema pasado de moda, continúa siendo de actualidad para la vida cultural, social y política de Estados Unidos. Por eso, un gran número de ellos se encuentra escribiendo acerca de cuestiones relacionadas con sus orígenes, su cultura y su idioma. Y es precisamente esta búsqueda, emprendida desde una perspectiva pluricultural y plurilingüística, la que sigue impulsándolos a diseñar una realidad latina no monolítica sino multifacética.

– La Societé des Poetes Francais, organización centenaria y por la cual han pasado los más renombrados poetas del mundo, recientemente invitó a Isaac Goldemberg a leer sus poemas.