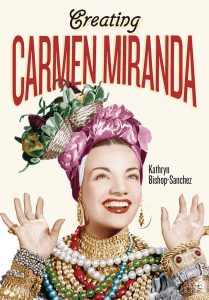

Creating Carmen Miranda

Kathryn Bishop-Sanchez

In the early hours of August 5, 1955, Carmen Miranda died in her Beverly Hills home at age forty-six. The day before she had filmed a sequence for the Jimmy Durante Show and, as the television program footage clearly shows, at one point she dropped to her knees and muttered she was out of breath. Durante, a quick improviser, told the band to stop the music and helped her up with the reassurance, “I’ve got your lines.” Recovering her breath, Carmen danced on: it would be her last filmed appearance. That evening Miranda, always the gracious hostess, invited friends to her house, and they talked and sang well into the night. When she retired to her room at around half past two, she collapsed again. She was found dead a few hours later that morning, fully dressed lying on the floor. Carmen Miranda had suffered a fatal heart attack.

The shock of Miranda’s premature death inundated the Brazilian and US media, which published the details of those last moments and retrospective appreciations of her career and rise to stardom, as her family, friends, and fans attempted to come to terms with the loss of such a beloved and unique “movie comedienne and dancer” at the (erroneously reported) age of 41.1 The press publicized the events following her death closely: the thousands of mourners who paid their respects as her body rested in state at Cunningham and O’Connor Hollywood Mortuary chapel, the smaller gathering of approximately three hundred close friends and family at the Requiem Mass in the Church of the Good Shepherd in Beverly Hills, and the description of Miranda’s burial attire—a simply tailored red suit and a rosary of red beads twined in her left hand—as she was laid to rest in a bronze coffin.2 Of the hundreds of funeral offerings, film director Walter Lang’s floral piece featuring a mixture of fruits on its base drew particular attention.

Brazil anxiously awaited the transfer of Miranda’s body to Rio de Janeiro to bring the samba ambassadress back home. Expressing the nation’s impatience, the Brazilian newspaper headlines lamented, “Miranda’s body is still in Hollywood” and transmitted collective rejoicing when finally there was confirmation the Brazilian government had sent a plane to bring her body home a week after her death on August 12.3 Returning the body to Brazil was vital for the nation to reclaim ownership of the deceased star and bring her celebrity trajectory full circle, while providing a physical symbol for their collective sorrow. While the United States mourned the passing of a vivacious and much-loved Hollywood star, Brazil had lost Carmen Miranda the national singer, integral part of the cultural patrimony, and greatest ambassadress of their music and nation, despite wide-spread reservations about her stylized baiana and the adulterated image of Brazil and Latin America that she had embodied.4 She was an extraordinary interpreter of the Brazilian people, and with Carmen Miranda’s death a period of her generation’s youth—the golden days of 1930s radio and the great Rio casinos—also vanished.5

Thousands lined the streets when Miranda’s coffin arrived from Rio’s Galeão airport and accompanied the fire-engine hearse as it drove slowly from one of Rio’s central squares, Praça Mauá, to Cinelândia, where from the evening of August 12 to the morning of the thirteenth hundreds of thousands of mourners paid their last respects to the star.6 The following day the coffin was closed and taken to its final resting place, the cemetery of São João Batista in Rio, with multitudes accompanying the funeral procession and collectively singing and humming some of Miranda’s most well-known Carnival marches and sambas. As her biographer Ruy Castro rightly states, it was Carmen Miranda’s greatest carnival with her people (550). The entire nation was in mourning, with newspaper headlines lamenting, “O Brasil perdeu Carmen Miranda” (Brazil has lost Carmen Miranda).7 Carmen Miranda’s death sealed the exceptionality of her stardom: she performed until the very end, and her last screen appearance was as a stylized baiana.

In the United States, Carmen Miranda is best remembered nowadays for her Twentieth Century-Fox films in which she stole the show with extravagant bare-midriff dresses, platform shoes, and outrageous fruit-basket headdresses, most filmed in gorgeous Technicolor. This is the signature look of the “Brazilian Bombshell,” the performer immediately recognizable for her fruit-laden headdresses and whose distinct appearance, unmistakable accent, dynamic dancing, and explosive, nonsensical singing made her easy to imitate. At the pinnacle of her success in the early 1940s, she was Hollywood’s most parodied entertainer as a cultural icon with appeal to a mass audience. The intense visual impact of her exaggerated, glamorous look—matched perfectly by her vivacious demeanor, gracefulness, enormous captivating smile, electrifying rhythm, impeccable accelerated diction, gyrating hips, and elegant hand movements—created an exhibition of stylized effeminacy and excessive female sexuality that for Hollywood would be the Carmen Miranda image. For the Hollywood musical of the wartime period, Miranda was a match made in heaven, with song-and-dance numbers that were always perfectly and elaborately executed, bringing Miranda to dominate at the heart of the show or film, even when she was not at the center of the action. Miranda remains a household name most prominently throughout Brazil, her home country, and the United States, where she performed from 1939 until her death, but Carmen Miranda’s widely circulated star image has not yet received thorough, critical analysis.

This is a book about the creation, interpretation, and imitation of Carmen Miranda’s image as filtered first through Brazilian society of the 1930s and then through Broadway and Hollywood from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s and the social, political, and cultural importance of this popular Hollywood icon, who has sustained interest to the present day. This study examines Miranda’s idiosyncratic celebrity sign and the values it intersects, such as ethnicity, exoticism, comedy, racial difference, and excessive femininity.

When Carmen Miranda came to the United States, the star system, which cannot be dissociated from its industrial setting and institutionalized competitive nature, was in full swing, with impresarios and producers extensively marketing and mythicizing their leading ladies and prime stars as a way to differentiate a company’s play or a studio’s latest release from all others on the market. The stars were at the core of this “product differentiation” (deCordova 46), even more so than the Broadway companies or the film studios themselves.

Given the screen homogeneity within Miranda’s star trajectory—her “immutability and substitutability of the narratives” (López 75)—discussions of her individual films reiterate and deviate little from the core of her image, and plot summaries of her films become negligible as far as a theoretical reading.8 In reference to her US films, I emphasize her construction as a popular icon whose fixed meaning and visual appeal invited its reproduction, imitation, and instant recognition.9 The meaning of Miranda’s image evolved from its Brazilian origins, yet for the most part in the United States she consistently represented notions of the exotic and otherness, which changed little throughout that part of her career when she corresponded fabulously to Hollywood studios’ Latin vogue.

Similar to other enduring icons, Miranda’s “renewability” (Curry xvi) stems from her adaptability to the point that she became a performative sign that itself engaged with the impact of her star image. Through camp sensitivity, in particular, I discuss Miranda’s own staged engagement with her over-the-top, stylized image, a concept that I refer to as her performative wink, which has eluded critics who perceive Miranda as being infantilized and manipulated as part of an institutionalized system of representation. It is my contention that to catch Carmen Miranda’s performative wink effectively requires an understanding not only of textual analysis—which is where most readings of Miranda’s performativity have found their limitations—but also of production history and conceptualization, including the more general historical, social, and racial context of her image and performance.

It bears emphasizing that, distinct from a biographical or descriptive text couched in historical evidence that aims to divulge the “true story” of the star and readings of Miranda’s films, this book focuses on the discussion surrounding the star that creates her depth and, whether contrived or verifiable information, represents and constructs Miranda’s stardom and her impact on popular culture and society at large. Several lines of inquiry motivate this approach: the emergence of the baiana image, its creation as an entertainment persona, its circulation as a cultural and media sign, and the shift from its initial creation to enhancement and parody, including self-parody.

Miranda as a performer crossed over several performative genres, from radio to stage, theater, film, and television. With the main focus on the visual aspect of Carmen Miranda’s performance, I leave the wealth of her radio performances and music recordings for a future study within radio broadcasting history and musicology. Likewise, the reader will notice that prominence is given to Carmen Miranda’s stardom during the Brazilian years and then her tenure with Twentieth Century-Fox, where she received top billing. While mention is made of her subsequent films that carry over her baiana image, these films add no further dimension to her stardom as she experienced a progressive fall from the limelight.

Miranda’s composite image has risen from innumerous written, visual, and aural representations: the films themselves and their trailers, photographic stills, recorded performances, record albums, and a plethora of promotional and critical texts about these performances, along with commercially produced fan discourse and written reports by contemporary commentators, news reporters, and the studio and theater agents. This study draws upon both contemporary and retrospective sources to discuss articles and illustrations that highlight certain aspects of Miranda’s star image at each moment of her career and, through these readings, aims to understand what is Miranda’s most enduring and prevailing impact. Through an extensive reading of contemporary articles written about Carmen Miranda during her star years and beyond, patterns can clearly be identified. I have examined a substantial representation of fan magazine, trade, and commercial articles from libraries, archives, individual collections, and online auctions. One archive in particular, the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills, holds a comprehensive collection of publicity stills, film exhibitor pressbooks, promotional posters and lobby cards, studio-produced biographies, and magazine and newspaper articles that provide a greater understanding of Miranda’s Hollywood stardom and from which I draw extensively. Many of these narratives in newspapers and fan and mass-market magazines often incorporate quotations from Miranda’s own words, contributing to the star’s composite image. These ancillary texts, produced by hack writers, gossip columnists, studio-sponsored reviewers, or sensationalist writers, participated in constructing the collective, mediated image of the star.

This multi-layered archival approach is indispensable to defining Miranda’s stardom. As John Ellis’s basic definition encapsulates, a star is “a performer in a particular medium whose figure enters into subsidiary forms of circulation, and then feeds back into future performances” (91). The challenges inherent to the nature of this work on Miranda’s stardom, at the intersections of theory, primary materials, and a vast corpus of secondary materials, drew me to the interrelated lines of race, gender, camp, and performativity. In the case of Carmen Miranda, as with many other stars from the period, there is still little integration of archival research with film and stardom analysis, perhaps due, on the one hand, to the obvious roadblocks to having access to pertinent materials that could never be all-inclusive and, on the other, to the complexities of gender, cultural, and racial politics that beg an interpretation of these materials beyond an anecdotal reading. This book aims to redress this critical oversight by drawing from textual analyses of Carmen Miranda’s performances and grounding them in a broader social, political, and racial context.

Although at times gaining access to certain films seemed close to impossible, over the years I was able to view all the films mentioned in this book; some released for commercial usage were borrowed through libraries or personal collections, bought through online auctions, or screened at the UCLA Film and Television Archives. The majority of Carmen Miranda’s Hollywood films are now available commercially on DVD with the release of the Carmen Miranda Collection (2008) or manufactured on demand.10 Unfortunately, of her Brazilian films, only Alô, alô, carnaval! (Hello, hello, carnival!, 1935) in its entirety and one segment of Banana da terra (Banana of the land, 1939) have been preserved.11

Transnational Stardom

Stardom contributes to the film narrative beyond the script and transcends the characterization of the players within the individual films. The pioneering work by Christine Gledhill, Edgar Morin, David Marshall, Richard Dyer, and the above-mentioned John Ellis all call for the study of stars as signs that link film to culture, politics, society, and historical contexts. Miranda’s star image becomes a site to explore the representation of foreignness, sexualities, gender difference, the spectacle of excess, parody, and the more general concepts of imagining Afro-Brazilianness in Brazil and Latinidade in the United States. Carmen Miranda was unique, and numerous were the industries surrounding her performances that chose, similar to Hollywood, to “capitalize on the economic possibilities of difference” (Hershfield xi). The blending of Miranda’s on- and offstage and screen personae created a multilayered matrix. One of my aims in this book is to explore the backwaters of the stage and film businesses surrounding her and her image as portrayed through an array of star publicity and media texts that expand her stardom through meaning “generated in the film text more generally” (Geraghty 183). In doing so, this exploration of Carmen Miranda’s stardom promises to be informative far beyond the study of media representation.

Always present at the background of this study is the premise that Miranda became a transnational star once her career took her from Brazil to Broadway and Hollywood. Her career drew its appeal and strength from her interstitial position between both countries: while not belonging here or there, she blended elements from both countries into a unique performative genre, defined across and beyond national lines.12 I will discuss the construction of her exotic image in the United States and how she transcends the stereotypical image of Latinidade by being fiercely unique. Although she was critiqued upon her return to Brazil after only a year abroad for being “too Americanized,” this harsh reception on the Carioca stage was a watershed in her development as a singer with North American international success. As a transnational star she was able to reflect upon her position as a samba singer and performer from an international perspective while remaining fervently attached to her Brazilian public. There is camp sensitivity in her transnationalism in that she could poke fun at her unforgiving audience and at her position as a misinterpreted star in Brazil at the beginning of a very promising US-based career.

While there are many definitions of the transnational available for critical co-option, the most prominent points to the persistence of the global in the local. Or, alternatively, we can consider that Miranda’s performance went through a process of transculturation, as famously theorized by Fernando Ortiz, which enabled her to attain and maintain her unique star appeal for a North American audience, most prominently during her first seven years in the United States—the years that correspond to her Broadway tenure and Twentieth Century-Fox contract. Transculturation, rather than acculturation, denotes a detachment from European ethnocentrism and is particularly well suited to depict Miranda in the United States through a three-dimensional performative dialogue that spans her entire career at the interstitials of American musical and popular entertainment, her early career and Brazilian background, and the Afro-Brazilianness of her baiana. More significantly than ever before, Miranda’s success as a transnational star forges a new dimension of Brazilian music and culture abroad, not only to the North American public but also to the rest of the world.

A Brief Biography

Carmen Miranda was born Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha on February 9, 1909, in Marco de Canaveses in northern Portugal. Before her first birthday, Miranda’s family immigrated to Brazil, a common destination for hundreds of thousands of Portuguese families during the first decades of the twentieth century. Miranda’s upbringing was marked by her traditional convent schooling, her employment as a sales clerk at several stores (including a much mythicized apprenticeship as a milliner at the upscale hat store “La Femme Chic” in downtown Rio), and the boarding house that her parents opened in the mid-1920s in the Lapa neighborhood, where boarders and daytime diners often included composers, artists, and musicians. The young Maria do Carmo mingled within this milieu and eventually met the composer and guitar player Josué de Barros in 1928. Soon after she adopted “Carmen Miranda” as her recording and stage name, she recorded her first two songs in 1929, followed the subsequent year by a major hit, Joubert de Carvalho’s “Taí,” which placed Miranda as the most popular voice of the radio for Carnival 1930.13 Later that year Miranda negotiated her first recording contract with RCA Victor and went on to record an impressive number of more than 250 songs, many written exclusively for her by composers such as Ari Barroso, Lamartine Babo, Assis Valente, and the above-mentioned Josué de Barros and Joubert de Carvalho—all major names of the time. From this period until her departure to the United States in 1939, Carmen Miranda was one of the main radio and stage voices of Rio and Brazil at large. Hers was a new, refreshing, high-pitched, and extremely rapid yet clear diction, to which she added her unique playfulness and interjected spontaneous Brazilian slang and humorous asides. She invigorated her live audiences with the energy of her highly dynamic performances, along with her contagious feelings of good will, delirious happiness, confidence, and charisma. She created a sense of closeness to her audience through fast-paced gestures and dancing eyes that mesmerized her public. Impish, photogenic, mischievously sensual, exuberant, fun, and funny, Carmen Miranda earned her Brazilian moniker, “a pequena notável” (the remarkable young girl). Her stage persona and style, which were ideally suited for live interactions with her audience, transferred seamlessly to the silver screen. Miranda starred in five Brazilian films, most notably as an up-and-coming radio star in the 1935 film Estudantes (Students) and in Alô, alô, carnaval! (Hello, hello, carnival!, 1935), in which Carmen and her sister Aurora famously sing the self-referential march “Cantoras do rádio” ([Female] radio singers). Discovered by Lee Shubert in February 1939 as she performed at the Urca Casino in Rio de Janeiro, Miranda secured a contract for the Broadway show The Streets of Paris and arrived in New York on May 17, 1939, accompanied by her band, Bando da Lua, thanks to the sponsorship of Brazil’s president, Getúlio Vargas.14 Because Miranda was a performer and entertainer molded under the nationalist umbrella of the Vargas regime, her flight to Broadway and subsequent North American acclimatization produced a hybrid performer whose heart remained loyally Brazilian on a stage far removed from her middle-class radio listeners and the societal elite of the fine Carioca stages. Almost immediately Hollywood scouts courted Miranda, and she made her first film for Twentieth Century-Fox, Down Argentine Way (1940), on location in New York because she was unable to leave The Streets of Paris long enough to go to Hollywood. She stayed with Twentieth Century-Fox until 1946, filming a total of ten films, all musicals, and then continued independently to star in another four films, none of any real note. She met her husband-to-be, David Sebastian, on the set of Copacabana (1947), and they were married after a short courtship on March 17, 1947. Other than an initially unsuccessful (and traumatic) return to Brazil in 1940, where she was accused of having become “too Americanized,” Miranda stayed in the United States for the next fourteen years, only returning once again to Rio de Janeiro in early 1955 to receive medical treatment for clinical depression, less than a year before her untimely death on August 5, 1955. In her short life, despite a bumpy ride at times along the way, she achieved transnational stardom in both North and South America and thereby completed what had appeared to be an impossible feat: reconciling the nationalist agenda of Vargas’s Brazil and Hollywood’s Pan-American Good Neighbor Policy.

From “Remarkable Young Girl” to “Brazilian Bombshell”: A Historical Frame

Carmen Miranda’s rise to stardom in Brazil as a popular singer, radio and recording artist, and later film actress, from the late 1920s to her departure to the United States in 1939, came at an auspicious period of greater cultural racial integration that ultimately brought samba to reign as Brazil’s national rhythm. Miranda’s performance style came to embody this felicitous ménage-à-trois of more inclusive gender, cultural, and racial politics, and her music became an important bridge across differences of race and class as she participated in the democratization of samba.

In the early 1930s, a vogue of sociology texts, such as Gilberto Freyre’s The Masters and the Slaves (1933), focused overwhelmingly on the positive contribution of the African diaspora to Brazilian culture, society, traditions, and demography, with a view to celebrating Brazil’s racial diversity as a point of national pride. This rise of a new sense of nationhood is indissociable from the repressive government of Getúlio Vargas, who took power after a bloodless military coup against former president-elect Washington Luís in 1930 and remained in power until he was likewise removed by a group of military officers in 1945. He is remembered as a pro-industrialist, nationalist, anti-communist dictator who consolidated his authoritarian rule through the imposition of the Estado Novo (New State) from 1937 to 1945. This period, commonly referred to in Brazil as the “Vargas era,” spanned the rise of staunch nationalism and national renewal, which symbolically and culturally involved the forefronting of Brazilian images, icons, and music and the democratization of national culture, ushering in a great number of middle-class artists with themes and styles of national appeal. Under Vargas’s impetus for national unity and identity, notoriously emblematized by the ceremonial burning of state flags in 1937,15 Carnival celebrations received state sponsorship as samba schools replaced political satire with national themes focusing on Brazilian traditions, culture, and history, and a more sanitized samba emerged around patriotic themes, with Miranda as one of its most popular interpreters. Under the aegis of Vargas’s quest to move the country toward greater modernity, Brazil developed its recording and cinema industries, along with a greater network of radio stations, which Vargas infamously used as a propaganda tool and a symbol of a united country.

In 1930, the film producer and director Adhemar Gonzaga founded Cinédia, which soon became the most important Brazilian film studio of the decade. Working with North American expat Wallace Downey, Gonzaga brought the Brazilian public the first sound movies and revolutionized the Brazilian film industry. Gonzaga’s productions bridged radio and cinema by riding the crest of the established radio industry, drawing from the talent of the live radio shows in vogue at the time, and bringing these popular voices to a public eager to see their favorite radio stars on the big screen. As one of the most sought-after popular-music voices of the 1930s, Miranda starred in Cinédia’s films along with many of her cohort of radio stars. Brazil’s nascent film industry stayed close to the vaudeville format, integrating musical numbers as a means to add cohesion to often loosely constructed plots.

Carmen Miranda arrived on Broadway as the US government was committing to move beyond military and imperialist control of Latin America and resolving to establish cordial relationships with its neighbors to the south under the auspice of Latin-oriented cultural outreach aimed at consolidating diplomatic cooperation and approximation. The launching of the Good Neighbor Policy, first coined by President Herbert Hoover during a goodwill tour following his 1928 election, is mostly associated nowadays with the foreign policy elaborated during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency (1933–1945), which grew out of the overlapping geopolitical imperatives of the US government and a pledge of no armed interventions with a will to promoting hemispheric solidarity. Politically, through Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy, North and South America’s differences could be transcended; culturally, in Hollywood films, this South American craze translated into the international languages of song, music, and dance, as screenplays drew heavily on South American locales, and studios sought to hire authentic or pseudoauthentic Latin players. Vivacious, talented, exotic, and beautiful Carmen Miranda was a godsend to the Good Neighbor Policy, and when Twentieth Century-Fox brought her to Hollywood, “almost singlehandedly Miranda spawned the studio’s South American cycle” (Woll, Hollywood Musical 115). Carmen Miranda became the muse of the Good Neighbor Policy, one of the most beloved representatives of South America on the US stage and screen, and moving beyond a more specific representation of her native Brazil, she soon came to represent “Latin America” more generically as a token Pan-South American actress.

Carmen Miranda’s arrival in Hollywood could not have been more perfectly timed. The late 1930s and the first half of the 1940s corresponded to the golden age of the Hollywood musical, and Miranda, already a seasoned singer, dancer, and performer on the Brazilian silver screen, stepped immediately into her role as the exotic, sensual, and vivacious Latina “other” at the heart of the musicals’ large production numbers and often at the center of the films’ hallmark moments. The musical is on all accounts a star-driven genre, and Carmen Miranda soon rose to symbolize Twentieth Century-Fox musical productions alongside her blond American costars Betty Grable and Alice Faye. Cinema was the most popular form of entertainment for the emergent middle class, and during wartime the musical became Hollywood’s dominant film genre (Woll, Hollywood Musical x). Adapting her performance style for a North American public, Miranda sang songs in her native Portuguese but also in English (and often catchy gibberish), and the hybrid performativity that resulted led her to the heights of transnational stardom in her new host country.16

*This fragmentis belongs to the title Creating Carmen Miranda (Vanderbilt University Press, 2016)

Notes

1. See, for example, “Carmen Miranda is Dead at 41; Movie Comedienne and Dancer,” New York Times, Aug. 6, 1955; “Carmen Miranda Dies of Heart Attack at Age 41,” Los Angeles Mirror-News, Aug. 6, 1955.

2. “Carmen Miranda Paid Final Tribute by 300,” Examiner, Aug. 9, 1955; “Requiem Mass Celebrated for Carmen Miranda,” Los Angeles Times, Aug. 9, 1955.

3. See “Ainda em Hollywood o corpo de Carmen Miranda,” Correio da manhã, Aug. 9, 1955; and “Confirmado: Sexta-feira no Galeão o corpo da Carmen!” Última hora [Rio de Janeiro], Aug. 9, 1955.

4. The baiana—as will be discussed in detail in Chapter 1, refers to a woman from the Northeastern state of Bahia and who, often in traditional dress, would carry her wares in baskets and on trays balanced on a turban on her head.

5. See Augusto Frederico Schmidt, “Carmen Miranda,” O diário [Santos—Estado de São Paulo], Aug. 21, 1955.

6. “Carmen Miranda Eulogized in Rio,” Los Angeles Times, Aug. 13, 1955.

7. Gazeta do rádio, Aug. 6, 1955.

8. For excellent summaries of Miranda’s films and a close reading of her Hollywood screen performances see Shaw, Carmen, 38-82.

9. For a discussion of the concept of an icon, see O’Connor and Niebylski, Latin American Icons, 1.

10. Available only in VHS format are Springtime in the Rockies (1942) and Scared Stiff (1953).

11. Contrary to Kirsten Pullen’s erroneous claim that Alô, alô, carnaval! is no longer extant (127), it was restored in 2002 and is available for viewing at the filmothèque of the MAM in Rio.

12. For a discussion of this in-betweenness see James Mandrell.

13. The Brazilian expression “taí” is a contraction for “está aí,” which can be translated as “here is” or “that’s” and is used to introduce someone or something.

14. See, for example, the article and telling title of Tinhorão’s “Carmen Miranda levou Bando da Lua aos EUA por inspiração de Getúlio” (Carmen Miranda took Bando da Lua to the United States thanks to Getúlio) that appeared in Jornal do Brasil on July 20, 1962.

15. See Eaton, Politics Beyond the Capital, 74 and 77–80.

16. See Clark, “Doing the Samba on the Sunset Boulevard,” for the Hollywoodization of Carmen Miranda’s music.

Posted: November 15, 2016 at 9:44 pm