Deaths, Men and… Sales

So Mayer

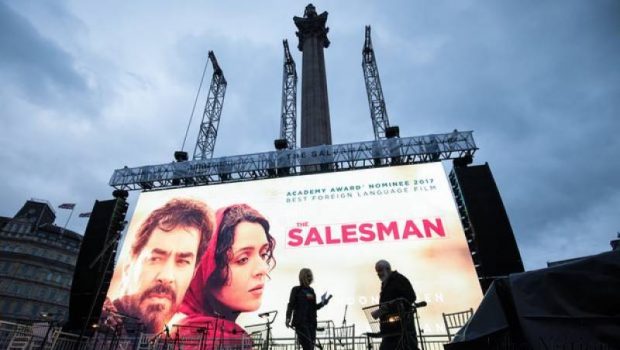

Spoiler alert: Details from the plot of the Oscar-winning film The Salesman by Iranian director Asghar Farhadi are revealed below.

It’s been twenty years since Buffy the Vampire Slayer first aired. So, in honour of a life- and medium-changing show, here is one of its all-time great speeches, from Season Four’s closing episode, “Restless”:

BUFFY: But what else could I expect from a bunch of low-rent, no-account hoodlums like you? Hoodlums, yes, I mean you and your friends, your whole sex, throw ‘em in the sea for all I care, throw ‘em in and wait for the bubbles, men with your groping and spitting all groin no brain three billion of you passing around the same worn-out urge. Men! With your… sales!

In a shared dream, Buffy and her school friends are performing a skewed version of Arthur Miller’s classic American drama Death of a Salesman, the 1949 play that also forms the centrepiece of Asghar Farhadi’s Oscar-nominated drama, The Salesman (Forushande). Farhadi’s seventh feature also skews the play, as life meets art and starts to affect the performances onstage. While there’s no disruption as out of keeping as Buffy’s tour-de-force tirade, during one performance Emad, the actor playing Willy Loman, lets his feelings fly at Babak, the actor playing his neighbour Charley; while during another Rana, Emad’s wife, who is playing Loman’s wife Linda, forgets her lines mid-scene.

Both interruptions are attributable to the same offstage events: at the start of the film, Rana and Emad have to evacuate their apartment building as it starts to collapse; desperate to find somewhere to live, they accept the offer of a flat that Babak owns, even though the previous tenant’s possessions are still stored in one room and the flat is in disrepair. Babak promises to ensure that the previous tenant, a woman called Ahoo, will come to collect her things but – Godot-like – she never materialises. Instead, one night after rehearsals, Rana is home alone when Emad calls from the supermarket; when the door subsequently buzzes, she opens it – but it is not Emad who enters the apartment. He finds her later at the hospital, her head bloodied and in bandages. A neighbour tells him that Ahoo was known to be engaged in sex work at the apartment, and suggests that the intruder was one of her clients.

Men’s worn-out urges are never far from the surface of Farhadi’s films, often for how they thwart women’s sanity and security, and disrupt any possibility of communication between the sexes. Although his male characters are rarely explicitly violent – Sepideh’s husband’s sudden outburst towards the end of About Elly comes as a huge shock – they often implicitly perpetuate the everyday violence of patriarchy through a lack of understanding towards wives and daughters, as is manifest in A Separation. In The Salesman, Rana comes to understand just how little Emad truly understands – or even wants to understand – her, as the film unravels into a quest for vengeance. Emad’s quest, specifically: his worn-out urge is to protect his honour against the slight done to it by –

Well, that’s the problem. First, he vents on Babak, blaming him for keeping them in the dark about the flat’s previous tenant. Then he tries to act the stern disciplinarian to the adolescent students in his literature class instead of the cool, friendly teacher he once was. And finally, he goes rogue, undertaking a vigilante pursuit of the truck left parked outside the building after the assault, its keys left behind in the apartment. He tracks down the truck at a bakery, and although he discovers that multiple bakery staff use it, he goes after a young man called Majid. At no point in this course of male heroics does he consult Rana: she has made it clear she doesn’t want to go to the police, out of complicated shame at having opened the door without checking who she was buzzing in, and possibly because she is not telling the full truth about the extent and nature of the assault. After forgetting her lines, she clearly asks for help and someone to talk to, not revenge.

That’s not to say that women can’t carry out vengeance: as Alice Lowe’s low-budget black comedy Prevenge shows, they absolutely can and do, even when seven months pregnant and occasionally getting stuck in a cat flap while fleeing the scene of a murder. It’s that Emad’s worn-out urge is to take revenge for something that didn’t happen to him. Unless, of course, he thinks of Rana as his property. That is the basis for films such as Irreversible (Gaspar Noe, 2002), a deeply conservative (and convenient) narrative trope in which the rape of a female character is the motivation for a male character’s (often spectacularly violent and equally spectacularly self-justifying) journey into the heart of darkness as they take over the centre of a story that is not about them. Emad, who thinks he’s so cool and modern, acting in an American play in which his character has a mistress, turns out to be incapable of not retrogressing into thinking of Rana as something he owns, and the attack on her as an attack against him.

The complicated set-up that places the assault in a new apartment makes the point about property very clear: Rana, like the apartment, is something to be traded between men. The home invasion and the assault on her person are mapped onto one another, especially as Rana repeatedly expresses her distress about the blood left in the bathroom – both hers, and that of the attacker who cut his feet on broken glass. Blood trails down the stairs of the building until Emad mops it away, despite the neighbours’ concerns that the police will want to see the evidence. Rana is too afraid to use the bathroom alone, or to enter the shower again – but instead of hunting for a new apartment, as per her request, Emad hunts down his own fantasy encounter with the assailant, acting like a low-rent, no-account hoodlum. Nowhere is that more evident than when he finds the man he thinks is the assailant and demands that he take off his shoes, to see whether his feet are cut. “Let me do it,” he demands, harking back to a previous scene in which Rana helped their friend’s young son Sadra go to the toilet; Sadra confidently tells Rana he can manage, and she leaves him to it. Yet Emad insists on removing the man’s shoes. Rana’s experience of violence has made her respect Sadra’s boundaries; Emad’s experience of violence against Rana has made him violate someone else’s.

Taraneh Alidoosti’s luminous performance as Rana, with all her anxieties and courage crossing her face every second, keeps pulling against the narrative focus on Emad, reminding us whose story – and whose body – is really at stake. Like Linda Loman, she is the ethical and dramatic centre of the narrative, but overshadowed by the way in which story appears to demand male action. The film ends with Rana and Emad both in make-up for a final performance of Death of a Salesman, cutting between their eyelines without ever establishing that they match – are they looking at each other, or are they both regarding themselves in the mirror? It’s a reminder of the last time we saw them onstage, where Rana delivered Linda’s closing monologue, spoken over Willy in his coffin. It concludes: “I made the last payment on the house today and there will be no-one home.” Each performance begins with Willy and Linda alive, and ends with Linda surviving him – watching The Salesman’s characters get ready to play Death of a Salesman’s characters, we remember that final scene is coming, and it belongs to Linda/Rana.

But the speech, and the play, also ends with a reminder that sales are a version of the same worn-out urge. To “take care” of women, whether financially or through physical violence, has the same effect of turning the women into objects that can be owned, bought and sold (as Ahoo’s possible profession also reminds us). Linda’s survival and Rana’s determination mirror each other’s, but so do Willy’s and Emad’s tawdry descent, their compulsion to repeat. It’s a bit on-the-nose that the man who eventually confesses to assaulting Rana is a clothes salesman (like Willy); more telling, though, is that Babak acts like another kind of salesman – an estate agent – to set off the whole sorry story, starting with wanting his previous tenant out (and an answerphone message implies he may have been more than her landlord).

Babak escapes the drama unscathed, still owner of the property that he forced Ahoo to vacate, and having drifted away from being Emad’s target. Rather than focusing on the friend and neighbour who turned his problem into an opportunity and created a dangerous situation, Emad goes after a working-class man–a weak-willed and even violent man, for sure, but not the author of the situation, nor its beneficiary. The class divide in Iranian society is a constant across Farhadi’s films, where as much of the narrative friction comes from the brushes between the property-owning classes and those who work in and around their properties, as between the genders. The dramatic opening of the film – the collapsing apartment building – underlines the increasingly precarious living situation of just-about-middle-class people in cities worldwide, facing high rents, shoddy construction, AirBnB, rising living costs, and pollution as well as a loss of public and cultural spaces. Rana may not want to use the shower in the apartment they’ve rented from Babak, but other apartments may not be easy to find or afford.

This attention to the everyday effects of capitalism is part of what gives Farhadi’s films their warm recognition from global audiences: while the particularities of life under the Iranian state play a role in his films, the broader intersections of gender and class may be inflected by local politics, but they contain frustrations and negotiations that are experienced in cities everywhere. In his Academy Award acceptance speech, delivered by Iranian-American astronaut Anousheh Ansari, Farhadi noted that the divisive politics of “us” and “them” represented by Trump’s is:

not just limited to the United States; in my country hardliners are the same. For years on both sides of the ocean, groups of hardliners have tried to present to their people unrealistic and fearful images of various nations and cultures in order to turn their differences into disagreements, their disagreements into enmities and their enmities into fears.

It’s not just the hardline politics of ethnic and religious division that unite the United States and Iran, it’s the effect of money, the attitude that everything is for sale and that wealth is the only value. It’s the money-makers, Farhadi suggests, who are “low-rent, no-account hoodlums,” and who continue to get away with it, while those who have to live in the narrowing spaces they grudgingly provide are set against each other to the death.

![]() Sophie Mayer is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound and The F-Word.She’s the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinemaand The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism andDocumentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is@tr0ublemayer

Sophie Mayer is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound and The F-Word.She’s the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinemaand The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism andDocumentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is@tr0ublemayer

©2017, Literal Publishing

Posted: February 27, 2017 at 11:44 pm