Thoughts from London

Reflexiones desde Londres

Adriana Díaz Enciso

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

After an unusually warm beginning of October, today (I’m writing this in the middle of the month) we woke up to a radiant, cold blue sky. Yesterday’s rain, which was also beautiful in its own way, seems to have swept away the remains of this year’s meteorological delirium in the island, and on this first day of proper Autumn, flooded with light, I think that there’s never been a more beautiful day. Like a prayer.

The prayer element is important. I don’t know how many more horrors in the history of this 21 st century, that we have been writing so shamefully from its start, will have accumulated by the time you read these words, but at this point we have already seen more than we can humanly bear.

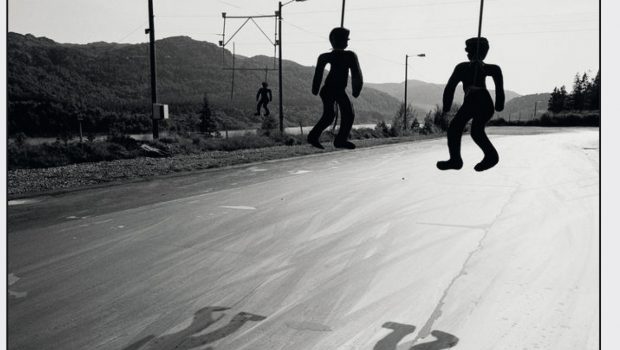

From the bus window, on my way to the overground, I see in a little park close to my house a crowd of children with their coaches, bathed in this light full of sparkles, training for football. There are also those flowers of an intense purplish pink that I can’t identify, shining with fierce determination, sagacious like animals. Further ahead, in the vast and generous Pymmes Park, a Muslim woman stands very still by a pram, together with a little boy, next to the brook. In front of them, a couple of geese—very still too, neck outstretched. They’re all so static they look like a picture, a postcard. A bit farther, a black dog with glossy fur is wagging its tail.

On Silver Street station’s platform, I can smell the coffee that the woman standing in front of me is drinking from a paper cup. The train is full of people, most of them looking at their mobile phones. I wonder what they’re watching; how many may be watching the news, or the long trail of misinformation and sterile uproar that the news have unleashed. A woman is making herself up, holding deftly a small mirror. The view during the short journey is, as usual, a gift: exuberant trees and undergrowth amidst the urban mesh, the houses’ back gardens; burning, bright red creepers heralding Autumn, at last; a church’s white tower in the distance among the gathering clouds, the sun behind them so bright that their outline shines like burnished silver and force you to squint your eyes.

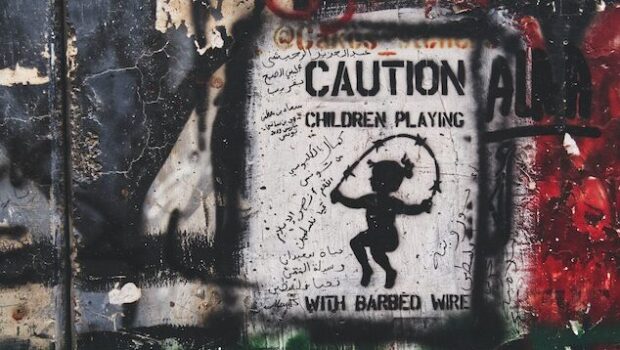

I see children, and wonder how they’re trying to make sense of what they’re no doubt seeing (it suffices to go to the supermarket and walk past the newspapers for all the darkness of the world to fall upon us); what they surely hear from adults. I also wonder what all the people I’ve crossed paths with today are thinking. Not all of them, of course, are thinking of the inexpressible tragedy that is taking place right now in the Middle East, but its shadow is inevitably upon us. It’s the weight of this world that we have created and in which, at the same time, we seem to have no agency whatsoever, its most brutal and bloody deeds beyond the slightest influence most of us can ever dream to have. An excessive weight upon people who’re simply trying to live their lives, something arduous in itself, because human life is arduous; because the financial crisis is brutal too, because an infinite, unmanageable number of threats seems to gather in the air. There will be fear in some (I do feel it), and also opinions: that insidious, neurotic plague which makes us “reaffirm our position”, whatever that means, in the face of any event, public or private, and that social media have done nothing but enhance to the most grotesque degree of absurd

and ignominy.

On the wake of Hamas’ monstrous terrorist attack on Israel last October the 7 th , and the no less horrendous response of Benjamin Netanyahu’s government, the first thing I saw in Twitter was hatred, barely disguised, fruit of that impulse for imposing one’s own political position, as if there were nothing more important in the world than that feeble signal of supposed authority before the spectacle of thousands of people murdered, wounded, others kidnapped; all of them, on both sides of the borders (and we now have to include Lebanon’s as well, given Hezbollah’s urge to join Hamas), terrorized victims of a violence that none of them deserves. No one, absolutely no one deserves what history, at the hands of murderers on both sides, is unleashing over their heads.

In the UK, just as in other countries, the casual, frivolous, stupid antisemitic and Islamophobic attacks started immediately, in the street, outside synagogues, in public transport. There have been large gatherings of the Jewish community and in support of Israel; vigils for the victims, and also pro Palestine demonstrations. The moment is so volatile, emotions are running so high, that the different discourses and intentions get mixed up. A lot of the people in those demonstrations, both in support of Israel and of Palestine, are right, and among them there are also those who for years have advocated for peace and dialogue between both peoples. Their voices get lost in all the shouting, but we must not forget that this desire for peace has existed within the zone of conflict, and outside as well, in exile, for decades, in many individuals and organisations whose work, and certainly their voice, are now being silenced by this savagery. We must not forget them.

I acknowledge the urgency to be out in the streets to demand the stop of the attack on civilians in Palestine. I don’t believe, however, in the legitimacy of slogans and banner-waving sustained, in some vociferous cases, by an inconceivable and incendiary ignorance that allows someone to think that Hamas represents legitimately the whole of the Palestinian people, and that the equally innocent victims of the attacks in Israel do not count. The day following Hamas’ attack, in Manchester, an individual declared in a demonstration, “We have all seen the scenes and it is the most inspiring act of resistance”, and Richard Barnard, co-founder of Palestine Action, declared about the “al-Aqsa flood” (Hamas’ name for its series of attacks last week) that “we must turn that flood into a tsunami of the whole world”. I stare at him, in the news, and can barely comprehend the degree of stupidity. In what way does he believe that such statements will help Palestine? People like him, do they really want peace, equality and justice in the Middle East, or war without end? Those who shout the louder are usually the ones who want nothing but an ongoing bloodbath.

On the 13th of October a teacher in Arras, France, was stabbed to death, and other two persons were wounded, with the Allahu Akbar cry, and though no direct link between this attack at the hands of a man of Chechen origin (a boy of merely 20 years old) with the current conflict between Israel and Gaza has been established, looking at the panorama, I fear that in many countries we will have to be prepared for the grim possibility of new terrorist attacks and hate crimes of all persuasions (in Illinois, 6-year-old Wadea Al-Fayoume was stabbed to death, his mother seriously wounded, for being Palestinian). There have already been evacuations, also in France, of the Louvre and Versailles, after bomb threats. In the United Kingdom we haven’t had any attack since the 2017 wave, and the sole idea that they will start again everywhere (in the name of what?; from which underworld of soul and intellect; from which pit of existential misery?) leaves me with a knot in my stomach. Though the question can be reframed like this: from which void of prospects and future, from which form of nihilism, that drives people to radicalization and blind violence, with different excuses, in so many parts of the world?

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s messages of solidarity with Israel would be fair and pertinent, had he not taken so long in also expressing his concern for the humanitarian crisis in Palestine. In the recent House of Commons’ session he said attacks against the Jewish or Muslim communities will not be tolerated, he declared that the UK is sending humanitarian aid to Palestine, that military support to Israel is only to “reinforce regional stability and prevent escalation” of the conflict, and he said several times that in his conversations with Netanyahu he has reiterated his support, but not without warning him that the international laws of war must not be broken, and that harm to civilians must be prevented. For the first time Keir Starmer, the Labour leader, seems to agree on something with Sunak. His discourse is almost identical, seemingly congruous and measured, but untenable in the face of the images we’re seeing from Gaza. The warnings to Netanyahu about respecting international law have come too late. This week, Israel has already committed war crimes. Why don’t they condemn them? Why, somebody tell me, isn’t it possible to condemn equally the massacre of innocents at the hands of one or the other perpetrator?

This morning on the train, I passed by Stamford Hill station, a predominantly Jewish neighbourhood, on my way to the London Buddhist Centre in Bethnal Green, the latter a fully multicultural area, with a lot of Muslim population. All these people, Jews and Muslims (my fellow citizens, my neighbours, my fellow creatures), must be having a tough time these days, with the possibility of a foolish attack against them on top of the horror we all share about the massacres.

Among the endless news, comments and analysis in the press, many are balanced and impartial, but this is amidst a dung heap of biased sensationalism, or sometimes not even biased: just sensationalism, pure and simple. Even so, for the sake of mental health and for the sake of integrity, we must focus on what is balanced and impartial, which is not easy to achieve in such an extremely complex conflict, and praise the work of those who right now are striving, with risk to their lives, to convey information about intolerable deeds with humanity, fortitude and probity.

Anything that I can say in terms of geopolitics is of no consequence here; it is being said already, much better than I could possibly do. I write this moved by an urgency that goes beyond the strictly political juncture. What do we know so far? That on the 7 th of October Hamas, as Yuval Noah Harari rightly said recently in the Washington Post and then in an interview, committed brutal acts of terrorism in Israel, and that it set to murder Jews house by house, just as the Nazis did in their time, only that this time it was in the very State of a people that has been constantly persecuted throughout its history. We can go on discussing, and it is in fact necessary, the decisions—complex, convoluted, difficult, erratic and not always serving noble causes—that gave as a result the British mandate for Palestine and later the violence in the region around the partition plan, as well as the crimes and violence that have resulted in countless victims on both sides for decades, but the truth of the matter today is that, in 2023, the Jewish people relived the horror of seeing part of its community massacred door by door, in addition to all the other horrors of the recent attacks that I don’t want to repeat here, in the name of a discourse that, behind the pretext

of justice for Palestine, states unambiguously the wish to exterminate the Jewish people (and, in passing, the Christinas too, in case you haven’t listened to Hamas’ leaders). On the other hand, Benjamín Netanyahu, a corrupt Israeli prime minister who faces considerable opposition in his country, who throughout his long mandate has hindered peace initiatives in the region and has been responsible for many crimes against civilians in Palestine, responded to the Hamas’ attack with a discourse of apocalyptic revenge which goes way beyond Israel’s legitimate right to defend itself, and launched the siege of Gaza, that has a population of two million, where civilians, who are innocent people too, are unfairly paying the price for Hamas’ atrocities, left without water, electricity or food, with their homes destroyed as well, and people being directed to a supposed safe region in the south only to be massacred there too, and more horrors that I do not want to repeat either. Hamas committed brutal attacks against civilians that are absolutely unjustifiable, and right now Israel is carrying out war crimes. Is it really possible to take sides between one group of massacred innocents and the other? On both sides of the border, many children have been

murdered, wounded, left traumatized. Let us understand this. We’re not talking of abstractions here.

The magnitude of the horror of what’s happening should move us to sobriety and to silence if we don’t have anything useful to say. These are human lives, all of them. Before this fact, quite frankly, what importance can our political position have? At moments I don’t even understand anymore what that means. I, who have always considered myself leftist, hesitate when I see others who think the same of themselves celebrating the massacre in Israel, justifying it out of the most stunning ignorance of what kind of organisation Hamas is, under whose rule none of these persons would surely survive. The same kind of leftists who celebrated the attacks to the twin towers and the Pentagon in 2001 and who defend Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. But I don’t understand either the demonisation of the whole of Islam and the Arab world that is the speciality of the contrary position, nor the defence of Israel’s current government, of the crime of the occupation and its endless abuses of the human rights of the—innocent—Palestinian population, and when we reach this point in the discussion I realise that I don’t want to hear anymore, not out of escapism, but because, in the face of such endless suffering and atrocities, our positions do not matter in the least.

With this I’m not saying that we should abandon political reflection, convictions and action, which would be absolute nonsense, but I do believe that there’s a dimension of elemental humanity that goes beyond that. I believe, in fact, that perhaps the most wholesome political action from those of us who are not there, in the face of such massacres of innocents, is the call for moderation, for the necessary pause of thoughtful silence before speaking, and for the contemplation of the suffering of our fellow human beings as such: our fellow men, women, children, people who’re simply trying to live, like you who’re reading this, like me, who writes it, regardless the nationality or the creed, be it religious or political. This was understood by Edward Said and Daniel Barenboim when they created their foundation and the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, a bid for fragile hope born from the awareness of two peoples’ most atrocious suffering. I am quoting here their vision,

as it appears in their webpage:

“We are not a political organization. We cannot solve the Middle East conflict. But we believe that the destinies of Palestinians and Israelis are inextricably linked and that we can help break barriers considered insurmountable. Music makes people emotionally receptive. The very structures and forms of music are central to human interaction. The West-Eastern Divan Orchestra opens up channels of communication based on equality, cooperation and justice for all. Our musicians don’t just listen to music: they listen to each other.”

I’m talking about something similar when I say that, sometimes, it is good to look beyond politics. “To talk about music, now!”, you will scold me, in exasperation. But I am talking about an enormously courageous initiative that insists on the need to rescue our humanity even in the most adverse circumstances; that relies on creation rather than destruction, from below, where we are, the majority of the population all over the world: far from any access to power.

Under the dazzling light, vertiginously beautiful on this cold autumn London day, light that bathes and blesses us all, light that gives me unreserved delight, I also feel like bursting into tears. I look, as far as I can bear it, at what is happening right now in Israel, in Gaza, but also in other parts of the world that unfortunately are less “news”, but where violence doesn’t stop, including our poor torn Mexico, and I feel a pressing yearning for a universal prayer. Not a prayer learnt from this or that religion, but the prayer of our common humanity. A prayer from and for us, who are also “the others”, beneath this diaphanous sky, perhaps empty, but not any less holy for that, just as the life of every single one of us who pass through this wounded world is holy.

*Foto de Jakob Rubner en Unsplash

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Tras un inicio de octubre inusualmente caluroso, hoy (escribo esto a mediados de mes) amanecimos con un cielo radiante, azul, y frío. La lluvia de ayer, que fue hermosa también, a su manera, parece haberse llevado los restos del delirio meteorológico de este año en la isla, y en este primer día de otoño como los dioses mandan, inundado de luz, pienso que no ha habido nunca un día más hermoso. Como una oración.

Lo de la oración es importante. No sé qué tantos más horrores se habrán acumulado en la historia de este siglo XXI, que tan vergonzantemente hemos venido escribiendo desde su inicio, para cuando ustedes lean estas palabras, pero a estas alturas ya hemos visto más de lo que podemos humanamente soportar.

Desde la ventana del autobús, rumbo a la estación del tren de superficie, veo, en un parquecito cerca de mi casa, a una multitud de niños y a sus instructores, bañados de esta luz llena de destellos, en un entrenamiento de futbol. Están también esas flores de un rosa intenso y purpúreo, que no logro identificar, brillando con fiera determinación, sagaces como animales. Más adelante, en el ancho y generoso Pymmes Park, una mujer musulmana está muy quieta junto a una carriola y un niño pequeño de pie, al lado del arroyo. Frente a ellos, dos gansos muy quietos también, alzando el cuello. Tan estáticos todos que parecen un cuadro, una postal. Más allá un perro negro de lustroso pelaje menea la cola.

En la plataforma de la estación Silver Street huelo el café que bebe en un vasito de cartón la mujer parada frente a mí. El tren va lleno de gente, la mayoría viendo sus celulares. Me pregunto qué ven; cuántos estarán viendo las noticias, o la larga cauda de desinformación y estéril vocerío que las noticias han desencadenado. Una mujer se maquilla. La vista durante el corto trayecto de tren es, como siempre, un regalo: vegetación exuberante entre el entramado urbano, los jardines traseros de las casas; ardientes enredaderas de un rojo vivo, anunciando el otoño al fin; la torre blanca de una iglesia a lo lejos entre las nubes que se empiezan a formar, el sol tras ellas tan vivo que sus contornos brillan como plata pulida y obligan a entrecerrar los ojos.

Veo niños, y me pregunto cómo estarán intentando encontrarle sentido a lo que sin duda están viendo (basta con ir al súper y pasar junto a los periódicos para que toda la oscuridad del mundo se abata sobre nosotros); lo que oirán comentar a los adultos. Me pregunto también en qué estará pensando toda la gente con la que me he cruzado hoy. No todos, claro está, piensan en la tragedia inexpresable que está ocurriendo justo ahora en Medio Oriente, pero su sombra cae, inevitablemente, sobre todos nosotros. Es el peso de este mundo que entre todos hemos creado y del que, al mismo tiempo, parecemos no tener dominio alguno, sus acciones más brutales y cruentas más allá de la más mínima influencia que podamos soñar con tener la mayoría de los humanos. Un peso desmedido sobre gente que está nada más tratando de vivir su vida, cosa ya ardua de por sí, porque arduo es el vivir humano; porque la crisis financiera es brutal también, porque en el aire parece cernirse un sinnúmero ingobernable de amenazas. Habrá miedo en algunos (yo, sin duda, lo siento), y también opiniones: esa insidiosa, neurótica peste que nos hace “reafirmar nuestra posición”, sea lo que sea que eso signifique, ante todo acontecimiento público o privado, y que las redes sociales no han hecho sino potenciar hasta llevarla a los grados más grotescos

del absurdo y la ignominia.

Tras el monstruoso ataque terrorista de Hamás a Israel el pasado 7 de octubre, y la respuesta no menos horrenda del gobierno de Benjamín Netanyahu, lo primero que vi en Twitter fue odio, apenas disfrazado, fruto de ese impulso de imponer la posición política propia, como si no hubiera nada más importante en el mundo que esa endeble señal de supuesta autoridad ante el espectáculo de miles de personas asesinadas, heridas, otras secuestradas; todas, a uno y otro lado de las fronteras (ahora tenemos que incluir la de Líbano también, dada el ansia de Hezbolá por unirse al odio delirante de Hamás), víctimas aterrorizadas de una violencia que ninguna merece. Nadie, absolutamente nadie merece lo que la historia, a manos de asesinos de uno y otro bando, está dejando caer sobre sus cabezas.

En el Reino Unido, al igual que en otros países, empezaron de inmediato los casuales, frívolos, estúpidos ataques antisemitas e islamofóbicos; en la calle, afuera de sinagogas, en el transporte público. En varias ciudades del país ha habido nutridas congregaciones de la comunidad judía y de apoyo a Israel, vigilias por las víctimas, y también marchas pro-Palestina. El momento es tan volátil, con las emociones tan a flor de piel, que los distintos discursos e intenciones se confunden. Mucha de la gente en estas manifestaciones, tanto en apoyo a Israel como a Palestina, tiene razón, y entre ella están también los que durante años han abogado por la paz y el diálogo entre ambos pueblos. Sus voces se pierden entre el griterío, pero no hay que olvidar que esa voluntad de paz ha existido dentro de la zona de conflicto, y fuera también, desde el exilio, durante décadas, en muchos individuos y organizaciones cuyo trabajo y, ciertamente, su voz, están siendo ahora acallados por la barbarie. No hay que olvidarlos.

Reconozco la urgencia de salir a la calle a exigir el cese del ataque a civiles en Palestina. No creo, sin embargo, en la legitimidad de consignas y un ondear de banderas sustentadas, en algunos casos vociferantes, por una ignorancia tan supina como incendiaria que permite pensar que Hamás representa legítimamente a todo el pueblo palestino, y que las víctimas también inocentes de los ataques en Israel no cuentan. Al día siguiente del ataque de Hamás, un individuo declaró en una marcha en Manchester: “Todos hemos visto las escenas, y es el más inspirador acto de resistencia”, y Richard Barnard, cofundador del grupo Palestine Action, declaró que era preciso convertir la “Tormenta de al-Aqsa” (el nombre que le puso Hamás a su serie sorpresiva de ataques) en un “tsunami por todo el mundo”. Me le quedó mirando en las noticias y apenas puedo comprender el nivel de estupidez. ¿En qué forma cree que semejantes declaraciones van a ayudar a Palestina? La gente como él, ¿quiere de verdad la paz, la igualdad y la justicia en Medio Oriente, o una guerra sin fin? Los que más gritan suelen ser quienes sólo quieren la continuidad del baño de sangre.

El 13 de octubre fue asesinado a cuchilladas un maestro en Arras, Francia, y otras dos personas resultaron heridas, al grito de Allahu Akbar, y aunque no se ha confirmado una relación directa entre este ataque a manos de un hombre de origen checheno (un muchacho de apenas 20 años) con el conflicto actual entre Israel y Gaza, viendo el panorama, me temo que en muchos países tendremos que estar preparados para la acerba posibilidad de nuevos ataques terroristas y delitos de odio de todos los signos (en Illinois, Wadea Al-Fayoume, de 6 años, fue muerto a cuchilladas, su madre gravemente herida, por ser Palestinos). Ya ha habido evacuaciones, también en Francia, del Louvre y de Versalles por amenazas de bombas. En el Reino Unido no hemos tenido ningún ataque desde la oleada de 2017, y la sola idea de que empiecen de nuevo por todas partes (¿a nombre de qué; desde qué inframundo del alma y el intelecto; desde qué miseria existencial?) me hace un nudo en el estómago. Aunque la pregunta se puede formular también de esta forma: ¿desde qué vacío de expectativas y futuro, desde qué nihilismo que conduce a la radicalización y a la ciega violencia, por excusas diversas, en tantas partes del mundo?

Los mensajes del primer ministro Rishi Sunak de solidaridad con Israel serían justos y pertinentes si no se hubiera tardado tanto en expresar también preocupación por la crisis humanitaria en Palestina. En la reciente sesión en la Cámara de los Comunes afirmó que no se tolerarán ataques contra la comunidad judía ni la musulmana, declaró que el Reino Unido está prestando ayuda humanitaria a Palestina, que el apoyo a Israel es solamente para “reforzar la estabilidad en la región y prevenir la escalada del conflicto”, y dijo repetidas veces que en sus conversaciones con Netanyahu le ha reiterado su apoyo, pero no sin advertirle que las leyes internacionales de guerra deben ser respetadas para prevenir el daño a civiles. Por primera vez el líder laborista, Keir Starmer, parece estar de acuerdo en algo con Sunak. Su discurso es casi idéntico, aparentemente congruente y mesurado, pero insostenible frente a las imágenes que nos llegan de Gaza. Las advertencias a Netanyahu de respetar las leyes internacionales llegan demasiado tarde. En esta semana, Israel ya ha cometido crímenes de guerra. ¿Por qué no los condenan? ¿Por qué, alguien respóndame, no es posible condenar por igual la masacre de inocentes a manos de uno u otro bando?

Esta mañana pasé en el tren por la estación de Stamford Hill, un barrio predominantemente judío, rumbo al Centro Budista de Londres en Bethnal Green, ésta última una zona acentuadamente multicultural, donde hay mucha población musulmana. Toda esta gente, judíos y musulmanes (mis conciudadanos, mis vecinos, mis semejantes), debe estarla pasando mal estos días, la posibilidad de un insensato ataque en su contra en cualquier momento sumada al horror que todos compartimos por las masacres.

Entre las innumerables noticias, comentarios y análisis en la prensa, muchos son equilibrados e imparciales, pero esto entre un muladar de amarillismo tendencioso, o a veces ni tendencioso siquiera: amarillismo nomás. Aun así, por salud mental y por integridad, hay que concentrarnos en lo equilibrado y lo imparcial, que no es cosa fácil de lograr en un conflicto tan extremadamente complejo, y encomiar el trabajo de quienes se están esforzando ahora mismo, con riesgo de su propia vida, por transmitir información de hechos intolerables con humanidad, entereza y probidad.

Cualquier cosa que yo pueda decir en términos de geopolítica sale sobrando aquí; se está diciendo ya, mucho mejor de lo que yo podría hacerlo nunca. Yo estoy escribiendo esto movida por una urgencia que va más allá de la estricta coyuntura política. ¿Qué sabemos hasta ahora? Que Hamás, como bien lo dijo en el Washington Post, y luego en una entrevista, Yuval Noah Harari, cometió el pasado 7 de octubre actos de terrorismo brutal en Israel, y que entró a matar judíos casa por casa, igual que lo hicieron los nazis en su momento, sólo que ahora en el propio Estado de un pueblo que ha sido constantemente perseguido a lo largo de su historia. Podemos seguir discutiendo, y es de hecho necesario, sobre las decisiones complejas, enrevesadas, difíciles, erráticas, no siempre al servicio de nobles causas, que dieron lugar al Mandato británico de Palestina y luego a la violencia en la región en torno al plan de partición, y sobre los crímenes y la violencia que han dejado innumerables víctimas de uno y otro lado durante décadas, pero el caso hoy es que en 2023 el pueblo judío revivió el horror de ver a parte de su comunidad masacrada puerta por puerta, sumada a todos los demás horrores de los recientes ataques que no quiero repetir aquí, en nombre de un discurso que, tras el pretexto de la justicia para Palestina, habla sin ambages del deseo de exterminio del pueblo judío (y, de paso, de los cristianos también, por si acaso no han escuchado a los líderes de Hamás). Por otra parte, Benjamín Netanyahu, primer ministro israelí corrupto, que enfrenta a una considerable oposición en su país, que durante su largo mandato ha obstaculizado las iniciativas de paz en la región y ha sido responsable de muchos crímenes contra civiles en Palestina, respondió a los ataques de Hamás con un discurso de venganza apocalíptica que rebasa el del legítimo derecho de Israel a defenderse, y que dio paso al asedio de Gaza, con una población de dos millones de personas, donde civiles, gente también inocente, está pagando injustamente el precio de la barbarie de Hamás, sin agua, sin electricidad ni alimentos, sus casas también destruidas, la gente dirigida a una supuesta región segura en el sur sólo para ser masacrada ahí también, y más horrores que tampoco quiero repetir. Hamás cometió ataques brutales absolutamente injustificables contra civiles, e Israel está ahora mismo incurriendo en crímenes de guerra. ¿Realmente es posible tomar partido por uno u otro grupo de inocentes masacrados? A ambos lados de la frontera, muchos niños han sido asesinados, heridos, traumatizados. Entendamos esto. No estamos hablando de abstracciones.

La dimensión del espanto de lo que está sucediendo debería movernos a la sobriedad y al silencio, si no tenemos nada medianamente útil que decir. Son vidas humanas, todas ellas. Ante esto, ¿qué puede importar, francamente, nuestra postura política? A ratos ya ni entiendo lo que eso significa. Yo, que me he considerado siempre “gente de izquierda”, dudo cuando veo a otros que se creen lo mismo celebrando la masacre en Israel, justificándola desde la más asombrosa ignorancia del tipo de organización que es Hamás, bajo cuyo mando ninguna de estas personas seguramente sobreviviría. El mismo tipo de gente de izquierda que aplaudió los ataques a las torres gemelas y el Pentágono en 2001 y que defiende la invasión de Ucrania a manos de Putin.

Pero tampoco entiendo la satanización del Islam y del mundo árabe entero en que se especializa la postura opuesta, ni la defensa del actual gobierno de Israel, del crimen de la ocupación y los interminables abusos de los derechos humanos de la población —inocente— palestina, y cuando llegamos a este punto de la discusión, me doy cuenta de que no quiero oír más, no por escapismo, sino porque ante semejante sufrimiento y atrocidades sin fin, nuestras posiciones no importan lo más mínimo.

No estoy diciendo con esto que debamos abandonar la reflexión, convicción y acción políticas, que sería un despropósito mayúsculo, pero sí creo que hay una dimensión de elemental humanidad que va aún más allá. Creo, de hecho, que quizá la acción política más íntegra por parte de los que no estamos ahí, ante semejantes masacres de inocentes, es el llamado a la moderación, a la necesaria pausa del silencio reflexivo antes de hablar, y a la contemplación del sufrimiento de nuestros semejantes como tales: nuestros semejantes, hombres, mujeres y niños; gente tratando simplemente de vivir, como ustedes que leen esto, como yo que lo escribo, sin importar la nacionalidad ni el credo, ya sea religioso o político. Eso lo entendieron Edward Said y Daniel Barenboim cuando crearon su fundación y la Orquesta West-Eastern Divan, una apuesta por la frágil esperanza nacida de la conciencia del más atroz sufrimiento de dos pueblos. Me permito citar aquí su visión, según aparece en su página web:

“No somos una organización política. No podemos resolver el conflicto del Oriente Medio. Pero creemos que los destinos de palestinos e israelíes están inextricablemente unidos, y que podemos ayudar a derribar barreras que se consideran insuperables. La música vuelve a la gente emocionalmente receptiva. Las estructuras y formas mismas de la música son fundamentales en la interacción humana. La Orquesta West-Eastern Divan abre canales de comunicación basados en la igualdad, la cooperación y la justicia para todos. Nuestros músicos no nada más escuchan música: se escuchan unos a otros.”

A algo parecido me refiero al decir que a veces hace bien mirar más allá de la política. “¡Hablar de música ahorita!”, me dirán, exasperados. Pero estoy hablando de una iniciativa de enorme valentía que insiste en la necesidad de rescatar nuestra humanidad aún en las más adversas circunstancias; que apuesta por la creación en lugar de la destrucción, desde abajo, donde estamos la mayoría de la población en todo el mundo: muy lejos del acceso al poder.

Bajo la luz deslumbrante, de vertiginosa hermosura de este día frío de otoño en Londres, una luz que a todos nos cubre y nos bendice, que me llena de gozo, quiero al mismo tiempo romper en llanto. Miro, hasta donde puedo soportarlo, lo que está sucediendo ahora mismo en Israel, en Gaza, pero también en otras partes del mundo que por desgracia son menos “noticia”, pero donde la violencia no para, incluyendo a nuestro pobre, desgarrado México, y siento el anhelo imperioso de una oración universal. No una oración aprendida de tal o cual religión, sino la oración de nuestra humanidad común. Una oración de y por nosotros, que somos también “los otros”, bajo este cielo límpido, quizá

vacío, no por ello menos sagrado, como es sagrada la vida de todos y cada uno de los que pasamos por este mundo herido.

*Foto de Jakob Rubner en Unsplash

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.