Sharp in His Observations

Rogelio García-Contreras

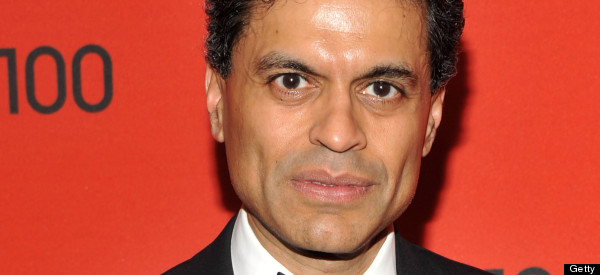

Fareed Zakaria

Fareed Zakaria

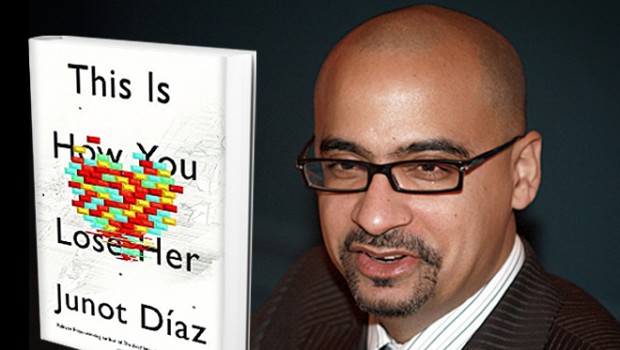

The Post American World,

W.W. Norton, New York, 2008.

Sophisticated in his analysis, sharp in his observations, Fareed Zakaria offers a comprehensive and reliable analysis of today’s world politics in his new best seller, The Post American World. With well documented cases, great reporting of pure facts and his unquestionable ability to incorporate into his examination the often ignored variable of culture and its effects on international relations, Zakaria’s central thesis of current world affairs is as simple as it can result useful: in a world where states are changing, America must change as well. His argument, liberal in essence, basically claims that American Foreign Policy cannot continue to develop over the wrongfully perceived bases of an omni-powerful America and a series of states that can be as distant as they are uncomfortable or as weak as they are hostile. In fact, according to Fareed Zakaria, the world—America included—often turns out to be a lot different from what American mainstream media, politicians and certain experts in the field describe or decide to conclude. By providing a strictly factual account of current global events, Zakaria writes that the world is not only far less belligerent than we assume, but a lot more prosperous than we often recognize.

In this sense The Post American World constitutes an interesting reading for that student or professional of international relations who might be eager to escape mainstream realist assessments of global politics. However, and aside from this refreshing contribution, Zakaria’s work never escapes the framework of a tacitly accepted discourse in the field. Such discourse provides the bases for a general understanding of the kind of unwritten rules that ambitious non-fiction authors should follow if they want to be successfully published in the American market.

So it is in this sense that I think Fareed Zakaria’s book loses a great deal of in-depth analytical potential and ends up missing a wonderful opportunity to become a revolutionary, non-ideological classic in IR. Zakaria’s insights on the relevance of culture, for instance, made up for an interesting and even optimistic reading of the first half of the book (see the passage on Hinduism, pp. 154-156), but then the author never uses his unquestionable talent to understand different cultures as a mean to reinterpret concepts, break stereotypes or escape assumptions. Rather, he just stick with “the facts”.

As a matter of fact, The Post American World often draws on the same kind of conclusions and risky assumptions American foreign policy makers or mainstream media ‘experts’ make while trying to explain the world (read for instance Zakaria’s comments on pages 11-16, 26-29, 245, or 251 regarding Muslims, terrorists and Mexicans). And even though Zakaria openly criticizes the old Republican rhetoric regarding terrorism or national security (see pp. 250-252), his strong liberal argument seems to be in a constant search for approval. By mentioning over and over again his own admiration and love for America, the author, in my opinion, loses legitimacy. For instance, in the first paragraph of his acknowledgements Zakaria writes that he “firmly believes that American power and purpose, properly harnessed, benefi t both America and the world”. This he writes as if, in a way, he were making a solid final statement just in case his own career or all the other similar statements in this book would not have given him enough right yet to barely criticize America as an Indian immigrant who has built a life and a family in the United States.

Thus, if we combine Zakaria’s need of self justification with some of his intrinsically problematic liberal views, we might be able to see how there is a serious and dangerous perversion inserted in Zakaria’s account of this unique new world. Perhaps rightfully, the author claims that in this Post American era ‘truths’ are being challenged, many notions confirmed, many concepts redefined, and many ideas have been opposed or simply destroyed. Yet, if he would have wanted to rescue his work from the dogmatic pre-determinations of those historical liberal or neo-liberal messiahs who, from the protected fields of Academia, suggest or assure that this is the end of history and that the liberal ideal has finally reached its manifest destiny; if he would have wanted to transform his book into a useful claim for justice, abundance, progress, good and freedom around the world; if he would have wanted to assess critically the claim that the establishment and enforcement of property rights is all we need to live harmoniously (see pages 60 or 134), then his book would not have ended up being more of the same.

In my opinion, Zakaria’s book is nothing else but a highly journalistic account of current events that includes, towards the end, the most commonly demanded feature that any ‘good’ (book) in the American market should have if it wants to capture the attention of both, the professionals and the aficionados: a recipe (see the section called New Rules for a New Age, pp. 231-250). Thus, although well organize and extremely insightful due to the author’s commitment to actual facts, The Post American World is quite an orthodox book in its approach to international politics, rather colloquial in its analysis, extremely superficial and even contradictory in its conclusions (read his first new rule and compare it to the second one) and, what is worse, the book never escapes the discourse of power in which most American analysts and foreign policy makers feel comfortable operating.

Posted: April 14, 2012 at 10:26 pm