The quoted “wor(l)d” of Liliana Porter

El “mu(n)do” citado por Liliana Porter

Fernando Castro

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

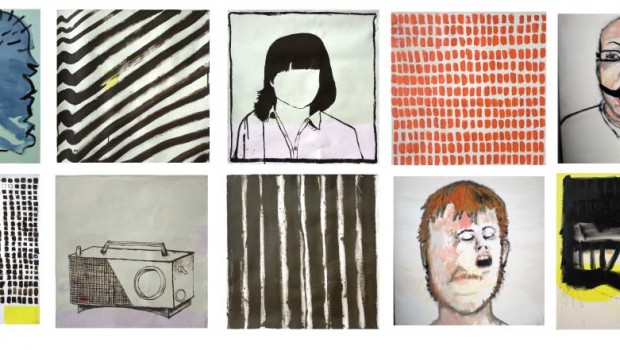

One of the most curious and paradoxical facts about Liliana Porter’s seemingly infantile oeuvre is the often complicated and obscure language that many critics use in order to discuss it. On the one hand, this peculiarity reflects the current state of critical language; but on the other hand, it also evidences the challenge of providing a serious interpretation for an oeuvre that at times appears to amount to nothing more than playing with dolls, while at others it poses true intellectual riddles.

Photography has been the central vehicle of Liliana Porter’s work since the seventies. Since the nineties the objects she photographs are plastic or porcelain figurines of political or religious personalities or part of the inventory of children’s toys and/or comic-book literature. On occasion the figurines are paired so that the viewer is enticed to imagine a dialogue between them. A seminal piece is Dialogue (1996) in which Pinocchio (the deceitful wooden marionette who —after making amends—“becomes” a “real” boy) engages in an imaginary conversation with Gregorio Hernández, the Venezuelan “physician of the poor,” who came to be regarded as a popular saint. Who is lying to whom? Some find a resemblance between the latter and Charlie Chan, the Chinese character of detective movies. Porter herself likens him to the self-portraits of René Magritte, the Belgian Surrealist painter—master of the visual lie—. In works such as The Explanation (1991) she has used Gregorio Hernández qua Magritte, but in To Go Back (2001) it would seem that the figurine has to be Charlie Chan returning to China and to a flat world. The representational lie is a constant in Porter’s oeuvre.

Two important critics, Gerardo Mosquera and Luis Camnitzer, have interpreted Liliana Porter’s photographic work by alluding to Jorge Luis Borges’s literature and René Magritte’s paintings. Porter’s interest in Magritte has a long history; she has quoted him in works like Magritte’s 16th of September (1975), The Great War (1975), La Luna (1977) and more recently, in La Clairvoyance (1999). As far as the relationship of Porter’s work with Borges’ literature, it cannot be visual but conceptual. Although in 1983 Porter produced the work Fragments with Borges’ Book depicting a sample of a book is not tantamount to representing the literary work in the book, whereas depicting a painting is to somehow represent its contents. In spite of the clues in Porter’s works that sustain the interpretations of Mosquera and Camnitzer, it seems counterintuitive that her photographs of kitschy porcelain figurines could fit in the aesthetic horizon of Borges’ cerebral oeuvre or even in Magritte’s Surrealism. Mosquera himself readily recognizes that “Porter has put Lichtenstein’s comics or Haring’s Mickey next to the ‘real’ Mickey.” The task at hand is therefore to understand how Porter’s oeuvre, whose visual antecedents coincide with Pop Art, somehow manages to subvert it.

A work like Dressed Penguin (1996)—which depicts an imagined dialogue between the photographic image of a clay figurine of a humanized penguin and the real figurine of a yellow bird sitting on a little stool—hides subversive traits in its innocent appearance. Porter subverts the genres of representation. Her figurines are already representations, her photographs are representations of representations, and her assemblages are a symbiosis of the former and the latter which forms a set as arbitrary as Borges’ category of animals that “can be drawn with a fine brush.”

Camnitzer’s use of Borges for interpreting Porter’s oeuvre seems more tangential and reflects his own view of Magritte’s work. Camnitzer writes that “Porter decided to confront reality more directly, either by using the objects themselves or through photography as a means to document them.” In this process, “what was refined was the quality of the dialogue of her objects. It was literally a question of establishing what things one object had to say to another and/or to the viewer.” Camnitzer’s main analogy of Porter’s works with Magritte’s oeuvre is that the dialogue between her figurines is reflected in Magritte’s works as “one image turns into the context for the other.” Although Camnitzer does not mention specific works by Magritte, one could propose the paradoxical Ceci n’est pas une pomme (1964), where the text in the painting truthfully denies what the picture verily depicts. Moreover, there are Porter works like Untitled with Fire (1989) that seem to follow Magritte’s surrealist agenda.

According to Camnitzer, for Magritte as well as for Porter, “it does matter who the characters are. (….) Porter’s art does not work with just any object. Her selection is careful and reflects not only the world delineated by Borges, by Alice in Wonderland, and by Magritte, but also by her very personal blend of astonishment, childishness, and humorous distancing.” Camnitzer only mentions two items from Borges’ literary repertoire, and it is not clear how they are reflected in Porter’s selection of figurines. One of the items is the aleph, the extraordinary sphere containing all other points in the universe; and the other is one of the protagonists of the story El Aleph, Carlos Argentino Daneri, who sets out to write a poem about every place on this planet. Nothing of the sort appears in Porter’s work —not even by analogy. Giving Camnitzer massive amounts of foreign aid, one might point out that the split between Borges the author and Borges the character in his dialogue with Carlos Argentino in some relevant way resembles those imagined dialogues between Porter’s figurines. That suggestion may be interesting enough, but how can a written dialogue resemble an imagined one? My question is not rhetorical but sincere.

Mosquera’s use of Magritte in interpreting Porter’s work is more radical. He considers Porter as “Magritte’s natural continuator.” According to Mosquera, Porter “plays with the irony that the work of the Belgian artist goes on to be part of the reality that he is questioning.” However, “there is a typical tone in her work that mixes humor and cynicism with loving warmth.” In La Clairvoyance (1999), she depicts an actual stone and a postcard of one of the Belgian artist’s paintings in which he paints an egg as a bird. The work insinuates that Porter has represented (if the act may be thus called) the potentially airborne postcard as an egg-like stone, or vice versa. Such are the ways of symbolization, as arbitrary as Borges’ animal classification in his Chinese Encyclopedia.

In spite of the parallels to Borges and Magritte pointed out by Camnitzer and Mosquera, Porter may be doing something that is simultaneously simpler and perhaps more interesting. She is letting her characters have the life that their iconic personalities have determined for them. This strategy may lead to all sorts of results depending on the figurine and the mix of representational media. In works where there are mixed media (photography/assemblage) the dialogue between two characters might be imagined to be about their ontological predicaments; like the Square talking to the Sphere about their kinds of existence in Edwin Abbott’s Flatland. This diversity in ways of existing is even impacting, as in the case of Stone (2000), or intriguing as in To Go Back (2001). In works where there is only one figurine and one dimension like in Minnie (1995), the represented space induces the viewer to feel the angst of a graphic and iconic existence.

Porter’s triptych Untitled Out of Focus Che (1991-1995) has received surprisingly little attention by the above-mentioned critics. The work shows a plate with Alberto Korda’s famous image of Che Guevara, the Communist revolutionist, and a figurine of Mickey Mouse. What could they talk about? In the early seventies, a book by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart called How to Read Donald Duck accompanied and fueled the controversy about cultural alienation in Latin America. One of the issues of the controversy had to do with the way the values of capitalism were inculcated in the minds of the young through comic book characters like Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck. Porter’s triptych conflates by means of the photographic effect of out-of-focus two characters that stood on opposite sides of that controversy. The out-of-focus technique, however, puts both Mickey and Che on the same plane, rendering them both agents of ideological penetration. Perhaps Mickey Mouse is explaining to Che that in Lichtenstein’s hands he too was a revolutionary in the struggle against elitist art.

Porter’s almost childish images bear a visual and playful resemblance to Pop Art works like those of Jeff Koons, Keith Haring and Roy Lichtenstein. Unlike the latter, however, the former show a speculative penchant for dealing with problems of ontology and paradoxes of representation. It is precisely this penchant that Borges, Magritte and Porter’s works share. However, Porter clearly gives her viewers the freedom to fill in the space between the quotation marks that surround her characters’ dialogues or monologues—in spite of Borges, Magritte and Porter herself—.

Uno de los hechos mas curiosos y paradójicos acerca de la obra aparentemente infantil de Liliana Porter es el complicado y oscuro lenguaje que muchos de sus críticos emplean para discutirla. Por un lado, esta peculiaridad refleja las tendencias actuales del lenguaje crítico; por otro, evidencia también el desafío de proveer una interpretación seria a una obra que a veces parece sólo un juego de muñecos mientras que otras veces plantea verdaderos retos intelectuales.

Desde los años setenta la fotografía ha sido el vehículo principal de la obra de Porter. Desde los noventa los objetos que fotografía son figuritas de plástico o porcelana que representan personajes religiosos, políticos, o parte del inventario de juguetes infantiles o de las tiras cómicas. En ocasiones Porter aparea las figuritas para que el espectador se imagine un diálogo entre ellas. Un caso ejemplar es Diálogo (1996) en el que aparece Pinocho (la marioneta mentirosa quien—al enmendarse—“llegó a ser” un niño “real”) en una imaginaria conversación con Gregorio Hernández, el “médico de los pobres” quien es considerado santo popular en Venezuela. ¿Quién le miente a quién? Hay quienes encuentran un parecido de este último con Charlie Chan, el personaje chino de películas de detectives. La propia Porter lo asemeja a los autorretratos de René Magritte, el pintor surrealista belga —maestro del engaño visual—. En obras como La explicación (1991) ella ha usado a Gregorio Hernández o a Magritte, pero en Regresar (2001) la figurita tiene que ser Charlie Chan en su camino de vuelta a China y a un mundo plano. La mentira en la representación es una constante en la obra de Porter.

Dos críticos importantes, Gerardo Mosquera y Luis Camnitzer, han interpretado la obra de Liliana Porter aludiendo a la literatura de Jorge Luis Borges y a la pintura de René Magritte. El interés de Porter por Magritte tiene un largo historial; lo ha citado en obras como El 16 de septiembre de Magritte (1975), La gran guerra (1975), La luna (1977) y más recientemente, en La clairvoyance (1999). En cuanto a la relación de la obra de Porter con la obra literaria de Borges, ésta no puede ser visual sino conceptual. Si bien es cierto que en 1983 Porter produjo la obra Fragmentos con libro de Borges, representar un ejemplar de un libro no es lo mismo que representar la obra literaria en el libro; mientras que representar una obra pictórica sí es representar su contenido. No obstante las evidencias en las obras de Porter que sostienen las interpretaciones de Camnitzer y Mosquera, prima facie pareciera improbable que sus fotografías de figuritas kitsch de porcelana calzaran en el horizonte estético de la cerebral obra de Borges o incluso del surrealismo de Magritte. El propio Mosquera admite que “Porter ha puesto los comics de Lichtenstein o el Mickey de Haring junto al Mickey `real´”. El desafío es entonces entender cómo la obra de Porter, cuyos antecedentes visuales coinciden con el arte Pop, de alguna manera lo subvierte.

Una obra como Pingüino vestido (1996) —que representa un diálogo imaginado entre la imagen fotográfica de una figurita de cerámica de un pingüino humanizado y la figurita real de un pájaro amarillo posado sobre un banquito— esconde rasgos subversivos en su aparente inocencia. Porter subvierte los géneros de representación. Sus figuritas ya son representaciones, sus fotografías son representaciones de representaciones, y sus ensamblajes son una simbiosis de las primeras con las últimas que forman un conjunto tan arbitrario como la categoría borgesiana de animales que “pueden ser dibujados con un pincel fino”.

El uso que Camnitzer hace de Borges para interpretar la obra de Porter pareciera más tangencial y refleja su propia visión de la obra de Magritte. Camnitzer escribe: “Porter decidió enfrentarse a la realidad más directamente, usando ya sea los mismos objetos o a través de la fotografía como medio para documentarlos”. En este proceso, “lo que se refinó fue la calidad del diálogo de sus objetos. Era literalmente cuestión de establecer qué cosas podía un objeto decirle a otro o a un espectador”. La analogía principal de las obras de Porter a la obra de Magritte es que el diálogo entre sus figuritas refleja la manera como en las obras de Magritte, “una Imagen se convierte en el contexto para otra”. Aunque Camnitzer no menciona obras específicas de Magritte, uno podría proponer la paradójica “Ceci n’est pas une pomme” (1964), donde el texto de la obra verdaderamente niega lo que la pintura verosímilmente representa. Es más, hay obras de Porter como Sin título con fuego (1989) que parecieran seguir la propia agenda surrealista de Magritte.

De acuerdo a Camnitzer, para Magritte tanto como para Porter, “importa quiénes son los personajes.(….) El arte de Porter no funciona con cualquier objeto. Su elección es cuidadosa y refleja ya no sólo el mundo delineado por Borges, por Alicia en el país de las maravillas y por Magritte, sino también su mezcla muy personal de asombro, aniñamiento y distanciamiento humorístico”. Camnitzer menciona sólo dos casos en el repertorio literario de Borges, y no queda claro cómo se reflejan en la elección de figuritas de Porter. Uno de los casos es el Aleph, la extraordinaria esfera que contiene todos los puntos en el universo; y el otro es uno de los protagonistas del cuento de El Aleph, Carlos Argentino Daneri, quien se propone escribir un poema sobre cada lugar del planeta. Nada similar aparece en la obra de Porter—ni siquiera por analogía—. Dándole a Camnitzer cantidades masivas de ayuda extranjera, uno podría argüir que el cisma entre Borges el autor y Borges el personaje en su diálogo con Carlos Argentino muestra una similitud relevante a los diálogos imaginados entre las figuritas de Porter. Esta sugerencia es bastante interesante, pero ¿cómo puede parecerse un diálogo escrito a un diálogo imaginado? Mi pregunta no es retórica sino sincera.

El uso que Mosquera hace de Magritte para interpretar la obra de Porter es más radical. Considera a Porter “la continuadora natural de Magritte”. De acuerdo a Mosquera, Porter “juega así con la ironía de que la obra del belga pasa a integrar la realidad que está cuestionando”. No obstante, “hay un tono típico de su obra que mezcla tiernamente humor y cinismo con una calidez amorosa”. En “La clairvoyance” (1999), Porter representa una piedra real y la tarjeta postal de una pintura del artista belga en la que pinta un huevo como un ave. La obra insinúa que Porter ha representado (si así se le puede llamar al acto) una tarjeta postal potencialmente aérea como una piedra con forma de huevo, o viceversa. Tales son las rutas de la simbolización, tan arbitrarias como la clasificación animal en su Enciclopedia China.

No obstante los paralelos a Borges y a Magritte señalados por Camnitzer y Mosquera, Porter podría estar haciendo algo simultáneamente más simple y quizás más interesante. Ella les permite a sus personajes llevar la vida que sus personalidades icónicas les han fijado. Esta estrategia puede conducirnos a todo tipo de resultados dependiendo del personaje y la mezcla de medios de representación. En las obras de medios mixtos (fotografía/ ensamblaje), el diálogo entre dos personajes puede imaginarse como una conversación sobre su disímil condición ontológica; como el cuadrado que le habla a la esfera sobre sus tipos de existencia en Flatland de Edwin Abbott. Esta diversidad de maneras de existir es incluso impactante como en Piedra (2000) o intrigante como en Regresar (2001). En obras donde hay una sola figura y una sola dimensión como es el caso de Minnie (1995), el espacio representado induce al espectador a sentir el angst de la existencia gráfica e icónica.

Es sorprendente que el tríptico de Porter Sintítulo che fuera de foco (1991-1995) no haya merecido la atención de los críticos antes mencionados. La obra muestra un plato con la famosa imagen del Che de Alberto Korda, el legendario revolucionario comunista, y una figurita del ratón Miguelito. ¿De qué podrían hablar? En los setenta, un libro de Ariel Dorfman y Armand Mattelart titulado Para leer al pato Donald acompañó y alimentó la controversia sobre la alienación cultural en América Latina. Uno de los temas de esta controversia tenía que ver con la manera como los valores del capitalismo eran inculcados en las mentes de los niños por medio de los personajes de las tiras cómicas como el ratón Miguelito o el pato Donald. El tríptico de Porter reúne por medio del artificio fotográfico del fuera-de-foco dos personajes que se situaban en polos opuestos de esa controversia. El fuera-de-foco, sin embargo, pone al ratón Miguelito y al Che en el mismo plano, mostrando a ambos como agentes de penetración ideológica. Quizá el ratón Miguelito está explicando al Che que en manos de Lichtenstein él también fue un revolucionario en la lucha contra el arte elitista.

Las imágenes casi infantiles de Porter guardan una similitud visual y lúdica con las de artistas del Pop Art como Jeff Koons, Keith Haring y Roy Lichtenstein. Pero a diferencia de éstas, las primeras muestran un afán especulativo de incursionar en aporías ontológicas y paradojas de la representación. Es precisamente este afán que las obras de Borges, Magritte y Borges comparten. No obstante, Porter claramente le da al espectador la libertad de completar el espacio entre las comillas que encierran los diálogos o monólogos de sus personajes —independientemente de Borges, de Magritte y de la propia Porter.