Words and Things: Rosana Ricalde

Las palabras y las cosas

Luciano Vinhosa

Traducción de Anahí Ramírez Alfaro

Time Changes Everything

Other authors have noticed that in Rosana Ricalde’s work, the instability between verbal syntax and visual structure expounds the image to the limit of the receiver’s poetic power. The fragile form knitted from her words and images doesn’t do more than seek meanings. But, what tool can be used to carve flesh from an object and extract its essence if time changes everything and never stops its flow? Thus, like dune landscapes, the meaning of her work moves along with the net of words thrown in order to capture it. We find ourselves inevitably subjected to tension: the infinite possibilities of language are juxtaposed with their inability to tell truth completely. Indeed, her works throw us into a pit of silence that is opened up by the words the artist builds her art with, as well as the words with which we try to understand them. If being lives in language, as Heidegger says, it is notable, however, that it’s instability is dynamically connected to our own instability—and even to our anxiety to learn it —because what we are (and what being is) only finds in words a short-lived representation.

If time changes everything, we may say that the instability on which the work struggles to build itself can be taken as a metaphor of everything that is changeable, impermanent and fragile. This is a rich contrast to man’s hidden will to live forever, unchanged, though experience only reminds him of his finiteness. This might explain the fact that art history is filled with portraits. It seems like the privilege of immortality, generally speaking, was restricted to pharaohs and monarchs, but that never stopped artists from making self-portraits in attempt to make the spirit remain through physical portrayals. It is said that Phidias left his sculpted image inside the Parthenon, and even before then, a certain Ni-ankh-Phtah engraved his facial features onto a monument in Ancient Egypt. However, the artist’s obsession with self-portraits is recent, related to the consciousness of individuality. So, if it is correct to say that at certain moments of its history, painting was directly associated with the idea of a mirror reflecting the physical world, then the self-portrait, with the artist’s face as its primary subject, was intended to be a mirror of his soul. The idea that empowered the self-portrait as a historic piece was that the appearance, despite being changeable and fragile, could participate in the subject’s inner life —but achieve greater stability. The self-portraits left by Rembrandt in the 17th century are, in fact, witnesses, and they point to the moment of passage—the turn of the 19th century—when European society psychologized itself.

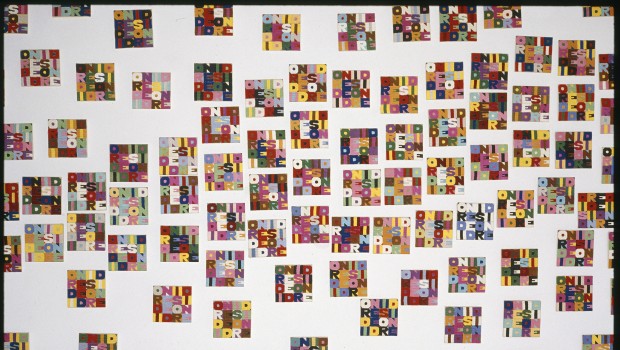

If poetry is the occupation of words through images, as Manoel de Barros states, poets, like visual artists, describe themselves in an attempt to establish their impermanent beings with images. In her self-portraits series, Rosana collects poems with the same title and brings them to a plane that’s traditionally occupied solely by painting. Giving each one of them a color, she reproduces the poems with embossing tape. It seems ironic that instead of a representation of the artist (her “self”), these are representations of the poets. It is also notable that the standard sizes the artist chose for these objects (50 x 46 x 2 cm) are the same as a small looking glass. Isn’t it through eye contact that we can expect to detect something the subject mistakenly missed? Does this strange subject—the now psychologized artist—reside more in the mirror than in the real world in his attempt of self-comprehension? The inevitable partition between the inner world and the outer world to which we were submitted by the process of civilization has set man on a course that makes him nostalgic for unity. Wouldn’t this gap between worlds be the ideal place for art to lay its foundations to live out its drama and extract from there the strength to continue its modern work? The self-portraits presented by the artist express it exceedingly well. In them, unity appears more compromised than promising as soon as each poet’s nature is known to be movable, like the images of the poems obliquely touched by the receiver’s eye on the surface of the “painting”.

After all, according to the same Manoel de Barros, images are words we missed. So, this anxious pause— the so-called relational space—is formed between the work and the subject facing it. Language tries to occupy it while it struggles with its own representation in this common space. Because the being is more movable than stable, time changes everything and the meanings are remade according to the context.

The self-regurgitating seas are also movable. They crash, they shake, and they turn everything into salt just as time changes everything. Rosana Ricalde’s seas, flowing with the currents that are birthed from handwriting, also acquire dynamic shapes. At some level, they form the necessary counterpoint to the previous works. The usual tension between verbal and visual signs is minimized in her Seas. The substantives of which they consist—the names of the seas—are almost dissolved into graphic substance. It is proved that thought, submitted to a continuous modular pattern, discovers itself each time the artist lets her hand go with the rhythmical frequency of the waves. Originality seems like the appropriate term to describe the posture that stands out, but here it’s meaning should be seen in a different light that usual. Instead of referring to the singularity of the subject or the particular character that atomizes it, it refers to its nullification through the adoption of the molecular gesture. Repetition, I believe, is the rigorous artistic exercise to which Rosana submits in order to forget the self, find spontaneity in the gesture again and return to the origin. Nevertheless, it’s not a representation of the “myself” of Expressionism, but the “ourselves” of Sufistic rituals and mantras.

In this sense, repetition can also be understood as a kind of moral exercise. It wouldn’t be casual or unnecessary to compare her Seas to eastern engravings, especially Hokusai’s, the exceptional Japanese artist who Rosana seems to be inspired by. It is known that traditional eastern art has related to imitation very differently than the western. The point is not that some of Rosana’s Seas to resemble Hokusai’s, but that they take from the master an inspiration for the perfect lines and rhythms that infuse her art with vitality. What counts is the inner likeness. Therefore, the artistic activity is an ethical act, capable of guiding life.

Time changes everything. Trees grow, men appear, days die… art is pure energy animating life. Furthermore, to what words can no longer say, an absolute sea of silence will be imposed. course that makes him nostalgic for unity.

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

El tiempo lo muda todo

Otros autores han notado que en el trabajo de Rosana Ricalde, la inestabilidad entre la sintaxis verbal y la estructura visual expone la imagen hasta el límite del poder poético del receptor. A través de la vista y del verbo, la frágil forma cuya estructura conforman no hace más que buscar significados. Sin embargo, ¿qué herramienta sería necesaria para tallar la carne de la cosa y extraer su jugo si el tiempo cambia todo y su flujo nunca se detiene? Por lo tanto, como un paisaje de dunas, el significado en sus obras va tan lejos como el lenguaje intenta lanzar su red de palabras para capturarlo. Nos encontramos inevitablemente sujetos a una tensión: por un lado están las posibilidades infinitas del lenguaje; por el otro, la imposibilidad de decirlas completamente. De hecho, sus obras nos arrojan a un hoyo de silencio que está abierto entre las palabras con las que la artista construye sus objetos, y aquéllas de las cuales nos valemos para tratar de aprenderlos. Si el ser vive en el lenguaje, como dice Heidegger, se observará también que la inestabilidad de la cosa está conectada dinámicamente con nuestra inestabilidad —e incluso con nuestra ansiedad por aprenderla— porque lo que somos (y lo que la cosa es) sólo encuentra una breve representación en las palabras.

Si el tiempo cambia todo, podemos decir que la inestabilidad en la que el trabajo lucha por construirse a sí mismo puede considerarse como una metáfora de todo lo que es cambiante, pasajero y frágil, en contraposición con el deseo escondido de permanecer que todo ser humano experimenta cuando se da cuenta de su finitud. Esto puede justificar el que la historia del arte esté llena de retratos. Parece como si el privilegio de la inmortalidad, en términos generales, estuviera restringido a los faraones y monarcas, pero eso no ha limitado a los artistas para hacer autorretratos, en un intento por hacer que el espíritu permanezca a través de la apariencia física. Se dice que Fidias dejó su imagen esculpida dentro del Partenón, y antes de eso, en el antiguo Egipto, un tal Ni-ankh-Phtah grabó sus rasgos faciales en un monumento. Sin embargo, la obsesión de los artistas por los autorretratos es reciente y está relacionada con la conciencia de la individualidad. Por lo cual, si de alguna manera es correcto afirmar que en ciertos momentos de su historia, la pintura estaba directamente asociada con la idea de un espejo que refl ejara el mundo físico; el autorretrato, con el rostro del artista como tema principal, tenía la intención de ser un espejo del alma de dicho mundo. La convicción con que se sustentó el autorre trato como una pieza histórica fue tal que la apariencia, a pesar de ser cambiante y frágil, podía participar en la vida interior de la persona (i.e. el tema de la composición) siendo esta vida interior más estable. Los autorretratos que dejó Rembrandt en el siglo XVII son más bien testigos y apuntan al momento —a finales del siglo diecinueve— en que la sociedad europea se sometió a una autorevisión psicológica.

Si la poesía es la ocupación de las palabras por imágenes, como asegura Manoel de Barros, entonces los poetas, como los artistas visuales, se describen a sí mismos en un intento por fijar con imágenes su ser efímero. En su serie de autorretratos, Rosana reúne poemas titulados como tales y los traslada a una superfi cie que comúnmente pertenece a la pintura. Tras asignarle a cada uno un color distinto, reproduce los poemas con una cinta grabada en relieve. Llama la atención el que en lugar de una representación de la artista (su “ser”) haya representaciones de los poetas. También es de notar que el tamaño estándar que escogió la artista para estos objetos (50 x 46 x 2 cm) sea el mismo que el de un espejo pequeño. ¿No es a través del contacto visual que podemos capturar algo que el sujeto (el tema y la persona) haya omitido por error? ¿Acaso este sujeto extraño —el artista ya sometido a una revisión psicológica— reside más en el espejo que en el mundo real, en un intento por auto comprenderse? La división inevitable entre el mundo interior y el exterior, al que fuimos sometidos por el proceso civilizador, ha fijado el curso del hombre occidental, quien ahora siente nostalgia por la unidad. ¿No sería la brecha entre estos mundos el lugar donde el arte habría construido los cimientos débiles para vivir su drama y extraer de ahí la fuerza para continuar su trabajo moderno? En los autorretratos presentados por la artista está más que explicado. La unidad aparece en ellos más comprometida que prometedora tan pronto se sabe que la naturaleza de cada poeta es móvil, como las imágenes de los poemas tocados indirectamente por el ojo del espectador en la superfi cie de la “pintura”.

Después de todo, de acuerdo con el propio Manoel de Barros, las imágenes son palabras que omitimos. Así que esta pausa de ansiedad —el así llamado espacio relacional— se forma entre el trabajo y el sujeto frente a él. El lenguaje trata de ocuparlo mientras busca su representación en este espacio común. Porque el ser es más móvil que estable, el tiempo cambia todo, y los significados vuelven a formarse de acuerdo con el contexto.

Los mares, que se regurgitan a sí mismos, también son móviles. Chocan, se agitan, convierten todo en sal y así el tiempo cambia todo. Los mares de Rosana Ricalde, a la deriva del flujo que viene de la escritura, también adquieren formas dinámicas. En cierto nivel constituyen el contrapunto necesario con sus trabajos previos. La tensión común entre signos verbales y visuales se minimiza en sus Mares. Los sustantivos que los constituyen —los nombres de los mares— están casi disueltos en una sustancia gráfica. Se ha comprobado que el pensamiento, sometido a un patrón modular continuo, se descubre a sí mismo cada vez que la artista deja ir su mano con la frecuencia rítmica de las olas. Originalidad parece el término apropiado para describir la postura que sobresale, pero aquí su significado debe estar de una manera distinta a la común. En lugar de referirse a la singularidad del tema, el carácter particular que lo atomiza, se refiere a la anulación a través de la adopción del gesto molecular. La repetición, me parece, es el riguroso ejercicio artístico al que se somete Rosana para olvidar el ser, encontrar de nuevo lo espontáneo del gesto y volver al origen. Sin embargo, no es una representación de “mí mismo” como en el movimiento expresionista, sino de un “nosotros mismos” como en los rituales sufistas y mantras.

En este sentido, la repetición también puede ser entendida como un tipo de ejercicio moral. No sería casual o innecesario comparar sus Mares con grabados del oriente, especialmente los de Hokusai, este excepcional artista japonés en cuyo trabajo parece estar inspirado el de Rosana. Es sabido que el arte tradicional de Oriente se ha relacionado con la imitación de un modo muy distinto al de Occidente. No se trata de que algunos de los Mares de Rosana de pronto se parezcan a los de Hokusai, sino de tomar del maestro una inspiración para las líneas perfectas y el ritmo que muestra la vitalidad del arte de Rosana. Lo que cuenta es el parecido interior. Por lo tanto, la actividad artística es un acto ético, capaz de guiar la vida.

El tiempo lo muda todo. Los árboles crecen, aparecen los hombres, los días mueren… el arte es energía pura que anima la vida. Más aún, el absoluto mar del silencio se impondrá sobre aquello que las palabras ya no pueden decir.

Very great post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wished to

mention that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts.

In any case I will be subscribing for your feed

and I’m hoping you visit more often!

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our

community. Your web site provided us with valuable info to work on.

You’ve done a formidable job and our entire community will

be grateful to you.