Fever Dream

Greg Walklin

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin. Translated by Megan McDowell

At least in American cinema, ecological stories are frequently contained in the legal thriller, in morality tales like The Rainmaker, or Erin Brockovich, or the less successful Promised Land. At least when it’s not producing a giant snake or shark or mutant, Hollywood likes to portray the environment as something that can be righted, as an opportunity to evaluate conviction and guilt. Think, also, of the Leonardo DiCaprio-produced documentary After the Flood, about global warming, or Al Gore’s much-lauded Inconvenient Truth about the same. But there is another dimension to these ecological stories, and neither Hollywood nor much in literature has placed the ecological story in the genre that it perhaps best belongs: horror. For what other genre could best describe the conditions of the water in Flint, Michigan? Or the bear bile farms in Laos? Or the ghostly-white corals off Cape York, as the ongoing annihilation of the Great Barrier Reef continues?

Horror is exactly what Samanta Schweblin has drawn up in Fever Dream, her first novel to appear in English, and a book of astounding unease and uncomfortableness. She achieves this, impressively, even though the entirety of the novel is a just a conversation between two characters: woman, Amanda, and a young boy, David. It’s clear that he is not her son—but little else is obvious. The point of their talking, as David sees it, is “to find the exact moment when the worms come into being.” This requires Amanda to recount a conversation she had with Carla, David’s mother, a little less than a week previous. What follows is David (whose words are italicized) and Amanda (not italicized) trying to pinpoint an elusive truth about their current conditions.

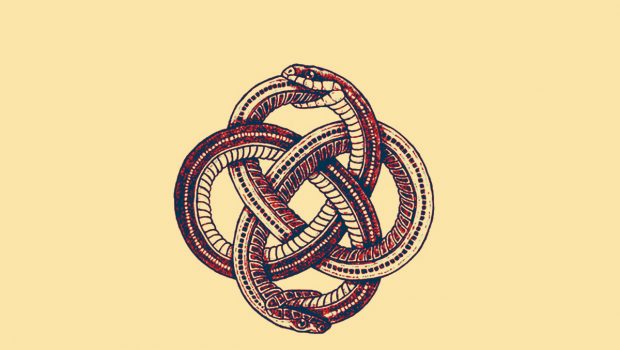

Amanda has fallen ill. David is estranged from his mother, Carla, who had relayed her concerns about him to Amanda. Amanda recounts this to David, and tells him everything started after David drank poisoned river water. Carla sought a magical cure, she told Amanda, which involved “the women in the green house,” who could see and read people’s energy and said a “migration” of David into two bodies would enable him to withstand the poisoning. If this all sounds like it is getting into the realm of fantasy, it is where the magical aspect of this novel ends, and probably where its creepiest moments begin.

For Fever Dream is truly less a dream and more a nightmare, although the kind that—like the best of horror—you cannot help but wanting to see through. The story hints at a sinister (“important” to David) scene of men unloading barrels from a truck, and seems to take off when a horse that drank the river water dies: his “lips, nostrils, and his whole mouth were so puffy he looked like a different animal, a monstrosity.” Amanda’s circumstances and situation grow less sure and less ostensibly safe. David did ultimately survive the poisoning, of course, but has changed, and taken up new hobbies—such as burying poisoned animals in his backyard.

This is made all the more creepy by Schweblin’s storytelling restraint—we don’t ever stray into Hollywood schlock here—and her sharp prose. Credit should also be given to Megan McDowell, who ably renders Schweblin’s Spanish into English with her typical directness and lucidity. McDowell seems to be translating much of the current, exciting Spanish literature into English, and Fever Dream is no exception. The book originally appeared as Distancia de rescate in Spanish in 2014; the Spanish title refers to the concept that Amanda employed with her daughter, Nina, to make sure she was always within “rescue distance,” or never too far to be saved.

Nina’s fate is yet another bit of tension in Fever Dream; endangered children play a central role, which makes Schweblin’s vision especially harrowing—from Amanda’s concern about Nina, to Carla’s about David, to children acting bizarrely and an entire town robbed of its youth. “[A]round here there aren’t many children who are born right,” David tells Amanda. Cloudy with poison, Amanda sees it for herself, as she is driving one night:

“It’s a group of people. I see them and I put the brakes on, they’re passing just inches away from the car. What are so many people doing together at this hour? They’re children, almost all of them are children. What are they doing crossing the street together, at that hour?”

Schweblin is from Argentina and now lives in Germany. As an Argentine residing in Europe, it seems impossible not to compare her to Cortázar, but the similarity is more than just superficial: Fever Dream possesses some of the same qualities that made some of Cortázar’s work unsettling, as in the sublimely scary “House Taken Over.”

Like a lit match, the flame here burns out quickly, as the book’s taut 183 pages should have you plowing through it in a single sitting. If you keep searching for the key to unlock this novel, you will likely come to the end still feeling a strong sense of foreboding—that the worst is still yet to come. But that is purposeful; there is an unsettling aura on every page of this book, straddling the line between fantastical and horridly real. Save perhaps the “migration,” it is all plausible without any suspension of belief, and the that, of course, is the most disturbing of all. “The poison was always there,” David tells Amanda, toward the book’s end.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction.

©Literal Publishing

Posted: April 19, 2017 at 8:37 pm