Official Gigantomachia

La gigantomaquia oficial

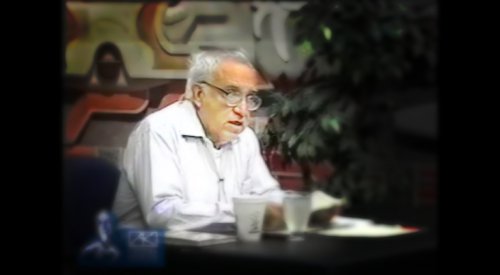

Carlos Monsiváis

Translated to English by Tanya Huntington Hyde

During the fall of 2007, when Carlos Monsiváis visited Houston, Anadeli Bencomo had the opportunity to talk to the author for Literal

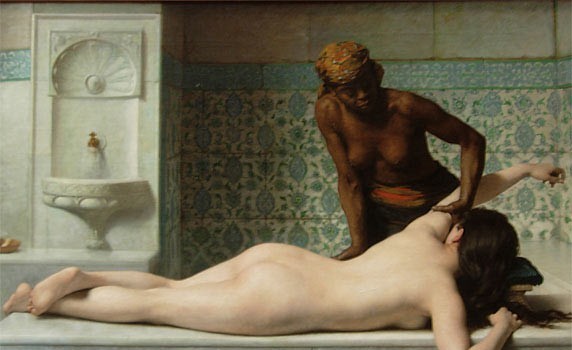

Anadeli Bencomo: While discussing some of the themes of your book, Imágenes de la tradición viva (Images from a Living Tradition, 2006), you referred to a specific episode in the history of Mexican art: the inauguration of National Museum of Anthropology (1964). As you mentioned during your talk, this museum played a leading role in terms of Mexican imagery by consolidating what is considered to be the nation’s cultural patrimony. Following this same train of thought, I’d like to ask you if you believe in the concept of “Mexican Art.”

Carlos Monsiváis: One cannot believe in the concept of Mexican art, because in such matters simply being genteel isn’t highly relevant. What I do believe in is the concept of art made in Mexico, art made outside Mexico by Mexicans, art that above all has to do with Mexican themes, and art that a community adopts as its own because of its subject matter, or out of custom, or out of an attachment to something that they believe belongs to them. But I don’t believe Mexican art exists, because it would be as if the hands of an essence could paint, print, or draw… I believe that what you experience, and how, is what transforms custom into national sentiment in terms of how art is seen.

AB: What role do cultural policies play within this transformation?

CM: They play a definitive role. For example, the presence of muralism was felt as early as the 1920s through conflicts generated by its artists, and the way they were rejected by the conservatives. But right when the big international exhibitions began, when the idea that Rivera, Siqueiros, Orozco, Tamayo represented Mexico came about, at that moment, there’s a change. The national community (or whatever you want to call it) discovers that it likes these artists not necessarily because they like what they’re painting, but because they are Mexican. And from so much liking what they do because they’re Mexican, they wind up accepting that they like it because it’s art, but this is already a longer and harder process. Without the cultural policies of the PRI’s government, much of what is now established would never have taken place. One great advantage of the National Action Party (PAN) administrations is that they don’t understand art at all. They aren’t the least bit interested, and therefore, they won’t impose an offi cial party line. Besides, Nationalism is already outdated, so—all of a sudden—they’d have to sponsor minimalist installations, or whatever, and that disconcerts them because they sincerely loathe art. Thus what we arrive at is a time when cultural policies oscillate between the desire for prohibition and bewilderment at what they can’t understand. But that grand stage when a whole series of painters and artistic trends was working, because behind them there was a government driving them, is over.

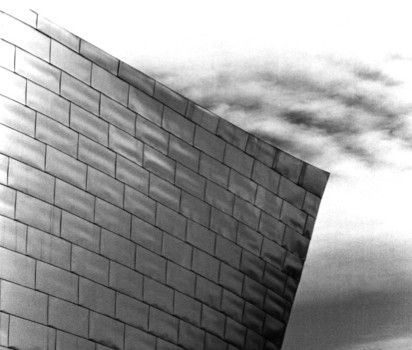

AB: However, despite this tendency you see in the PAN government, the official project of the Vasconcelos mega-library was forged in Mexico City during the Vicente Fox administration. What do you think of this initiative: was it a necessary project, or a useless enterprise?

CM: This mega-library business is typical in every Mexican administration, since governments need a monumental work that consecrates them and one can associate with them: the Temple of Diana at Ephesus… but they’re not pagan; the hanging gardens of Babylon… but that would require an architectural masterpiece; the pyramids of Egypt… which can’t be done because there’s no more room in the Federal District and they’d have to expropriate too much land, which would be very costly… So what do they come up with? The National Center for the Arts, which is a disaster, because they never integrated it. Simply put, they’re buildings linked only by the impossibility that buildings could ever run away. They haven’t captivated an audience or created a different ambiance. So then what occurs to Vicente Fox, or whoever’s idea it was? Something monumental, which is then connected to the notion of a Mega-library in the Mexican capital. They’d previously launched a campaign called “Mexico, a nation of readers” which was very interesting, because the day it was launched they brought in a soccer player, an actress from Televisa and a journalist (none of whom were highly qualifi ed in terms of their fondness for books) to promote this project led by Fox, who as a candidate had once told a group of artists and intellectuals: “Unlike those of you who were educated reading books, I was educated cloud gazing.” But instead of taking the next step and forming a cloudiary, he takes on (or is convinced to take on) this Mega-library, which, from the name itself, is truly deplorable. Objections are raised: what’s truly needed is to strengthen the regional library system, and with all the technology and data we have today, constructing a mausoleum is absurd; he doesn’t have to create a library like Harvard’s, or anything of the sort. Yet Fox couldn’t care less whether or not there are objections because, among other things, to him the book is an alien object that, having been denied place in his home, has no place in his imagination either. Therefore he relentlessly embarks on a library with a gargantuan budget of 2.1 billion pesos, a ridiculous sum, in a part of the city that borders on highly impoverished neighborhoods. Forgetting that it’s been built on a freatic layer, which is going to evolve into a situation lethal to books. Then they build a botanic garden that they say, with a generosity that still makes me blush, will be looking good within the next fifty years. This garden will also have dramatic consequences for the books. And then they have a storage capacity for 300,000 books in this megalibrary, none of which were printed before 1980. The entire project is so absurd that I find it hard to believe, although criticism no longer does any good at all. The problem with criticism around the world today is that it doesn’t matter; criticism already blends into the background noise, criticism has no infl uence, it doesn’t determine anything and from so much non-determination, it becomes inaudible. That’s where the trouble begins. Overall last year, thirty thousand books were lost to water: they were damaged beyond repair, because books aren’t used to swimming… The disaster goes on from there until, recently, they had to close the mega-library due to other numerous problems. This project was doomed from the start. I think that from now on, what we need to demand from cultural projects is humility; the era of gigantomachia has passed, because these projects aren’t feasible either in terms of the State’s economic capacity, or the demands of citizens, which revolve mostly around projects that are within reach.

AB: Within this panorama of official gigantomachia and grandiloquence, cultural alternatives arise such as the recently inaugurated museum of El Estanquillo, which exhibits many of Carlos Monsiváis’s private collections. What is the importance of initiatives like this one? Might we say that a different kind of cultural policy is to be found behind these projects?

CM: In Mexico today, there’s enough room for alternative museums, a space that is being fi lled nicely. But this is fundamentally true in Mexico City, with very few exceptions in some provincial locations. You’d have to say that this alternative space also has something to do with the gigantomachia I referred to before, but in a different sense. The museum we’ve attempted (“El Estanquillo”)—and in whose execution I was not involved—seeks to recover a past sustained by personal taste, not history, not sociology, and not nationalist desire. I like prints from the People’s Graphics workshop, I like comic books, I like pro wrestling, I like photographs —both of the caliber of Lola and Manuel Alvarez Bravo or Nacho López, as well as historic photos, photos of Zapata’s cadaver—but everything has to be “vintage.” If not, it doesn’t fulfi ll the requirements of my collections. For thirty-odd years I dedicated myself to collecting and one night, I found myself at dinner with these two guys. I told them what I was gathering and they offered to help me and I thought, well, maybe they really mean it, right? One was the city mayor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and the other a businessman, Carlos Slim. Both of them came to an agreement, and they helped me with the museum project. López Obrador gave us a magnifi cent site, a neoclassical building, and Slim gave us the profi ts from a record store he owns to help us pay the salaries of museum employees. That was our starting point. This alternative curatorial concept really works, as demonstrated by the fact that “El Estanquillo” was inaugurated four months ago and already 65,000 people have visited it, which is quite a lot for Mexico City. “El Estanquillo” isn’t the only museum in this regard, there’s a museum of Economic History that is doing extraordinarily well; there’s a place called Indianilla Station for new, postmodern art that is also working optimally, which demonstrates that there’s a public for this sort of less traditional museum. However, the museum par excellence in Mexico City continues to be the Museum of Anthropology because it founded an idea, slanted if you will, on a historic trend of tradition and national patrimony. The next museum in order of importance is Frida Kahlo’s, due to any explanation you prefer: she’s a great painter, a woman who suffered, of feminist attitudes. The third in terms of visitors is the National Museum of Art, and then comes us, which is really saying something. The fact is that between the Museum of Anthropology, the Frida Kahlo, the National and the other museums in Mexico City there’s a historic gap; but what the example of “El Estanquillo” shows us is that there’s also room for places that young people visit. The recreation of Mexican taste at “El Estanquillo,” has caught a lot of attention. Now there are going to be ten traveling shows, because there are 15,000 pieces in storage and 480 being exhibited, so the idea is to have traveling shows of José Guadalupe Posada, Miguel Covarrubias, and Diego and Frida—on a minor scale—, because basically it consists of representations of both fi gures. However, this example doesn’t speak to us about cultural policy so much as a desire to demonstrate that taste has a way of imposing itself over big budgets. Taste that requires a minimal investment because it’s popular taste, but not in the sense of being the opposite of Art with a capital “A,” given that what I proposed for the museum was a blend of high and pop culture. Not to set them at odds, but in order to show how they’re integrated within popular taste, because an appreciation for what surrounds us is what reveals its artistic quality.

Durante el otoño del 2007, Carlos Moniváis visitó la ciudad de Houston. Anadeli Bencomo tuvo la oportunidad de conversar con el escritor donde realizó una entrevista para Literal

Anadeli Bencomo: Al abordar algunos de los temas de su libro Imágenes de la tradición viva (2006), usted se refirió a un episodio particular de la historia del arte mexicano, el momento de la inauguración del Museo Nacional de Antropología (1964). Según nos comentaba en su charla, este museo tiene un rol protagónico en la consolidación dentro del imaginario mexicano de aquello que se entiende como patrimonio cultural de la nación. Siguiendo esta línea de reflexión, quisiera preguntarle si cree usted en la idea del “Arte Mexicano”.

Carlos Monsiváis: No se puede creer en la idea del arte mexicano, simplemente porque el gentilicio no tiene mucho que ver en estos asuntos. Lo que sí creo es en la idea de un arte hecho en México, arte hecho fuera de México por mexicanos, arte que tiene que ver sobre todo con temas mexicanos y arte que una comunidad adopta como suyo por la temática, por la costumbre, o por la afición a lo que consideran les pertenece; pero arte mexicano no creo que exista pues sería como si las manos de la esencia pintaran, grabaran, dibujaran… Creo que lo que se vive, y muy fuertemente, es el modo en que la costumbre se transforma en sentimiento nacional en la manera de observar el arte.

AB: ¿Y dentro de esta transformación, qué rol juegan las políticas culturales?

CM: Juegan un rol definitivo. Por ejemplo, la importancia del muralismo estaba ya presente en la década de 1920 en los pleitos que provocaban sus artistas, en el rechazo que les tenían los conservadores; pero en el momento en que comienzan las grandes exposiciones internacionales, y cuando se inicia la idea de que Rivera, Siqueiros, Orozco, Tamayo, representan a México, en ese instante hay un cambio. La comunidad nacional (o como se le quiera llamar) descubre que le gustan estos artistas porque son mexicanos, no porque les guste necesariamente lo que pintan, y de tanto que les gusta lo que hacen porque son mexicanos, acaban aceptando que les gusta porque es arte, pero eso ya es un proceso más largo y difícil. Sin las políticas culturales del gobierno del PRI, mucho de lo que ahora se ha establecido no tendría lugar. Una gran ventaja de los gobiernos del Partido de Acción Nacional (PAN) es que no entienden nada de arte, no les interesa en lo más mínimo y, por tanto, no van a imponer ninguna línea; porque además el Nacionalismo ya pasó y entonces tendrían que –de pronto– patrocinar las instalaciones sobre el minimalismo, o lo que fuera, y eso les desconcierta porque ellos detestan sinceramente el arte. Entonces a lo que vamos es a un momento en el cual las políticas culturales van a oscilar entre el deseo de prohibición y el desconcierto ante lo que no entienden, pero ya pasó esa gran etapa en la cual toda una serie de pintores y de tendencias artísticas funcionaban porque detrás había un gobierno que los impulsaba.

AB: Sin embargo, a pesar de esta tendencia que usted reconoce en los gobiernos del PAN, durante el mandato de Vicente Fox se fragua el proyecto oficial de la megabiblioteca Vasconcelos en el DF mexicano. ¿Qué piensa usted de esta iniciativa: es un proyecto necesario o una empresa insensata?

CM: Lo de la megabiblioteca es lo típico de cada mandato mexicano, pues los gobiernos necesitan tener una obra monumental que los consagre y con la que uno los asocie: el Templo de Diana en Efesos… pero ellos no son paganos…; los jardines colgantes de Babilonia… exigiría una obra maestra de arquitectura para que esto sucediera; las pirámides de Egipto… no se puede porque ya no hay espacio en el DF y tendrían que expropiar demasiados terrenos lo que sería muy costoso… ¿Qué se les ocurre entonces? El Centro Nacional de las Artes, que es un desastre porque nunca se integró y simplemente son edifi cios coaligados por la imposibilidad de que éstos se escapen, que no han retenido un público ni creado una atmósfera distinta. ¿Qué se le ocurre a continuación a Vicente Fox o a quien se le haya ocurrido? Algo monumental y esto tiene que ver con la idea de una Megabiblioteca en la capital mexicana. Antes habían lanzado una campaña que se llamaba “México: un país de lectores” y fue muy interesante porque el día del lanzamiento llevaron a un futbolista, a una actriz de Televisa y a un periodista (ninguno de los tres muy califi cados en cuanto a su afi ción a la lectura) para promover este proyecto liderado por Fox, quien como candidato le había dicho a un grupo de artistas y de intelectuales: “A diferencia de ustedes que se formaron leyendo libros, yo me formé viendo las nubes”. Entonces, en lugar de hacer lo que procedía, que era una nuboteca, se lanza (o lo convencen de que lo haga) a esta Megabiblioteca que ya desde el nombre era verdaderamente triste. Se le objeta que de lo que se trata es de fortalecer el sistema regional de bibliotecas y que ya existiendo toda la tecnología e informática, es absurdo levantar un mausoleo, que él no tiene que crear una biblioteca semejante a la de Harvard, ni nada por el estilo. Sin embargo, a Fox le da exactamente lo mismo que objeten o no porque, entre otras cosas, para él el libro es un objeto extraño que, como no tuvo lugar en su casa, no tuvo lugar en su imaginación. Se lanza así a algo despiadado en una zona de la ciudad que colinda con sectores absolutamente populares; con un presupuesto descomunal construyen una biblioteca que cuesta 2100 millones de pesos, lo cual es una cantidad desaforada. Se les olvida que está levantada sobre un manto freático, lo que va a dar por resultado una situación que para los libros es fatal. Luego construyen un jardín botánico que, con una generosidad que todavía me ruboriza, dicen que se va a ver bien dentro de cincuenta años. Este jardín también va a tener consecuencias dramá- ticas para los libros y luego tienen un acervo para esa megabiblioteca de trescientos mil libros, ninguno de los cuales se imprimió antes de 1980. Todo el proyecto es tan desaforado que me parece increíble, aunque la crítica no sirve para nada. Un problema de la crítica actual en el mundo entero es que da igual. La crítica ya forma parte del ruido lejano; la crítica no infl uye, no determina y, de tanto no determinar, se vuelve inaudible. Empiezan los problemas y, sobre todo, el año pasado se pierden treinta mil libros por el agua, se mojan irremediablemente pues los libros no están acostumbrados a nadar… Allí empieza el desastre hasta que recientemente tienen que cerrarla por otros numerosos problemas. Este proyecto está condenado desde el principio y yo creo que la humildad es lo que ya empieza a exigirse en proyectos culturales, ya pasó la era de la gigantomaquia pues sus proyectos no los permite ni la capacidad económica del estado, ni la necesidad de los ciudadanos que más que todo está centrada en ofertas al alcance.

AB: Dentro de este panorama de la gigantomaquia oficial y su grandilocuencia, surgen alternativas culturales como el recién inaugurado museo del Estanquillo, donde se exhiben muchas de las colecciones personales de Carlos Monsiváis. ¿Qué importancia tienen iniciativas como ésta? ¿Podríamos decir que hay detrás de estos proyectos una política cultural de distinta índole?

CM: Hay actualmente en México un espacio para museos alternativos que se está cumpliendo muy bien, pero esto se da fundamentalmente en la ciudad de México, con muy pocas excepciones de algunos lugares de la provincia. Habría que decir que este espacio alternativo tiene también algo que ver con la gigantomaquia a la que me refería anteriormente, pero de otra manera. El museo que nosotros intentamos (“El Estanquillo”), en cuya realización yo no tuve nada que ver, busca la recuperación de un pasado que está sustentado en el gusto, no en la historia, no en la sociología, y no en el deseo nacional. A mí me gustan los grabados del taller de la Gráfi ca Popular, me gustan los cómics, me gusta la lucha libre, me gustan las fotos, tanto de la calidad de Lola y Manuel Alvárez Bravo o Nacho López, como las fotos históricas, las fotos del cadáver de Zapata, pero todo tiene que ser vintage, si no no cumple las regulaciones de mis colecciones. Durante treinta y tantos años me dediqué a coleccionar y una noche me encontré en una cena con dos tipos, les conté de lo que estaba yo reuniendo y se ofrecieron a ayudarme y yo pensé, pues a lo mejor hablan en serio, ¿no? Uno era el jefe de gobierno de la ciudad, Andrés Manuel López Obrador y, el otro, era el empresario Carlos Slim. Los dos se pusieron de acuerdo y me ayudaron con el proyecto del museo. López Obrador nos dio un lugar portentoso, un edifi cio neoclásico, y Slim nos dio la renta de un lugar de discos que tiene para ayudarnos a pagar los salarios de los empleados del museo. Esto fue nuestro punto de partida. La idea de esta alternativa museográfi ca sí funciona, tal y como lo demuestra el hecho de que “El Estanquillo” se abrió hace cuatro meses y ya han asistido 65 mil personas, lo que es muchísimo para la ciudad de México. Y “El Estanquillo” no es el único museo en este sentido, hay un museo de la Historia de la Economía que está funcionando extraordinariamente; hay un lugar que se llama Estación Indianilla de arte nuevo, postmoderno, que también está funcionando óptimamente; lo cual demuestra que sí hay un público para este tipo de museos menos tradicionales. Sin embargo, el museo por excelencia en la ciudad de México sigue siendo el Museo de Antropología porque ésa es la formación en una idea si se quiere sesgada, de una vertiente histórica de la tradición y el patrimonio nacional. El siguiente museo en orden de importancia es el de Frida Kahlo, lo cual responde a todas las explicaciones que ustedes quieran, una gran pintora, una mujer que sufre, una feminista en la actitud. El tercer museo en materia de visitantes es el Museo Nacional de Arte y luego estamos nosotros, lo que es muchísimo. El caso es que entre el Museo de Antropología, el Frida Kahlo y el Nacional y el resto de los museos del DF hay un salto histórico; pero lo que demuestra el ejemplo de “El Estanquillo” es que sí hay espacio para lugares que visiten los jóvenes. Como hay en “El Estanquillo” una reconstrucción del gusto mexicano, eso ha llamado la atención. Ahora va a haber diez exposiciones itinerantes porque el acervo es de 15 mil piezas y están expuestas 480, entonces se trata de que haya exposiciones itinerantes de José Guadalupe Posada, de Miguel Covarrubias, de Diego y Frida –en un nivel menor– pues se trata primordialmente de representaciones de ambos personajes. Sin embargo, este ejemplo no nos habla tanto de una política cultural, como de un deseo de mostrar que el gusto tiene maneras de imponerse sobre el gran presupuesto. Un gusto que requiere una inversión mínima pues es un gusto popular, pero no en el sentido de lo opuesto al Arte con mayúscula, pues lo que yo quería proponer para el museo era una mezcla de alta cultura y cultura popular, no para contraponerlas, sino para mostrar cómo van integradas dentro de un gusto popular, pues el aprecio a lo que a uno lo rodea es lo que descubre su calidad artística.