Pitol Is and Is Not Mexican: About El mago de Viena

Tanya Huntington

Up until recently Sergio Pitol (Puebla, 1933) was one of the best-kept secrets in Mexican literature. However, the recent announcement that he has been awarded the Premio Cervantes—perhaps the most prestigious literary prize in the Spanish language— implies that he has now conquered Europe as well. In a sense this is only fitting, given that he began to publish literature as a member of Mexico’s diplomatic corps while residing in France, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary and the former Soviet Union.

Pitol has always been quintessentially cosmopolitan. During his lengthy trajectory as a translator, he acted as a portal, providing a broad public with access to the works of some of the lesser- known authors of Eastern Europe.

In fact, it is his predilection for the flower seldom seen that perhaps best defines Pitol’s approximation to literature. His early works, such as El tañido de una flauta (1972), Juegos florales (1982) and El desfile del amor (1984) foreshadowed the current trend among some Latin American authors to reject the legacies of the politically committed and largely utopian fiction produced by the generation known as the “boom.”

From the outside, authors such as Pitol may seem to lack ambition in comparison to the likes of Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa or José Donoso. However, looks can be deceiving: their works form part of unique literary genealogies that respect neither time nor place, carefully assembled by the authors themselves to include a wide array of diverse eras and cultures. These eclectic spheres of influence reflect not the experience of a nation, but that of the individual writer.

To my knowledge, Pitol has not yet been recognized as one of the predecessors of a new generation of authors—one that includes David Miklos, Pablo Raphael and Tryno Maldonado, among others—who do not attempt to engineer the Great Mexican Novel. Rather, they create exquisite works of fiction for the “happy few” that could have been written anywhere, by authors of any nationality. There are no chiles en nogada to be found in their books. Their emphasis is more on style than structure. They defy labels. Those who, like Pitol, are ultimately successful in mastering this literary sleight of hand will perhaps not be as easy to classify within a national context or an academic curriculum or a literary canon as, for example, Carlos Fuentes. They are destined either to write the brilliant but little known books read largely by other authors or, under more favorable circumstances, to become as timeless and universal as Jorge Luis Borges.

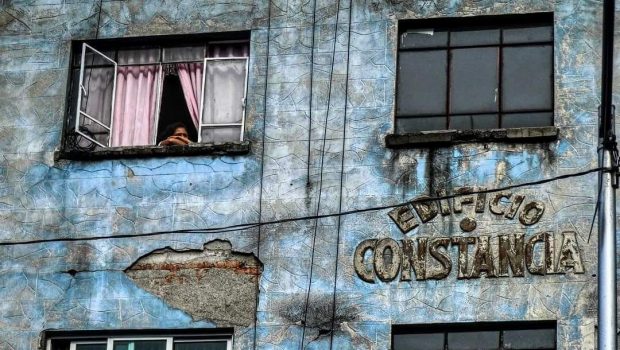

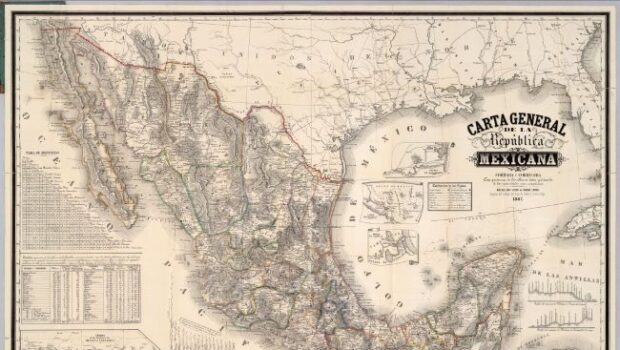

This is not to say that Sergio Pitol is not really Mexican —it would be equally absurd to claim that the author of Hombre de la esquina rosada was not Argentinean. Rather, Pitol is and is not Mexican. In fact, the title of his most recent memoirs, El mago de Viena or The Magician of Vienna, summarizes this paradoxical identity rather well. The book begins with a Borgesian ficción in which Pitol describes both the plot of El mago de Viena, a nonexistent title pertaining to the genre of pulp fiction—or “light literature,” as it’s known in Mexico—;and its respective review, written by a controversial, flamboyant and equally nonexistent literary critic named Maruja La noche-Harris. The protagonist of this pseudonovel is not Sigmund Freud who, incidentally, was nicknamed the Magician of Vienna but a criminal mastermind dedicated to victimizing amnesiac damsels in distress. This magician of Pitol’s invention is not even from Vienna; he resides on a street named after the Austrian capital located in Mexico City. A word evocative of Old World traditions, swallowed whole by the Leviathan of a postmodern megalopolis.

The melodrama of El mago de Viena exists only as one of Pitol’s false memories. On the surface, his description of a book he never read acts as a sign posted for the benefit of all those who believe in the absolute divide between fact and fiction, warning them to read no further. But it is also an affirmation of a dual identity, a declaration to the effect that authors who, like Pitol, were raised in postcolonial worlds have the distinct advantage of having fully assimilated the European tradition (the Austrian Vienna) while also dominating that of their native lands (the street of Vienna in Mexico City): the literary equivalent of having your cake and eating it too.

In keeping with the tempo of a Viennese waltz, El mago de Viena is the third in a series of memoirs published by Pitol. It is the final beat that both echoes and concludes the measure that began with El arte de la fuga (1996) and El viaje(2001).

In this latest compendium, what Pitol has lived is recounted strictly on a par with what he has read or what he has written. Once again, the term “memoir” is to be understood only in a non-orthodox sense. He includes lengthy quotes from his own books and those written by others, placing writer and reader on equal footing. Fiction invades autobiography and vice versa as one of many tricks the mind can play.

Pitol’s narration in El mago de Viena leaps from one topic to the next indiscriminately, following a pattern of associations similar to those practiced in our own minds as we try to remember. For example, through the years our recollection of a summer vacation may become less vivid than the memory of the book we read during the trip, or the travel diary we consult. In this sense, Pitol’s experience in Venice is no more or less real to him than Thomas Mann’s.

The crux of El arte de la fuga was Pitol’s own past; that is to say, a childhood reminiscent of Greek tragedy in which he lost his mother, father, and sister in quick succession. El viaje was about the difficulty of establishing his identity under these tragic circumstances. In El mago de Viena, Sergio Pitol as author, reader and human being struggles against time to preserve his memory against the onset of a devastating illness. Its final pages reproduce a journal kept in Havana, Cuba, where, like a tropical Hans Castorp, he travels in order to acquiesce to an experimental cure.

All that remains for a quickly growing body of readers is to recognize not the fiction, but the fact that Sergio Pitol has successively won each of these lifelong battles in the pages of his own written works.

Tanya Huntington is a contributing writer at Literal. Follow her on Twitter at @TanyaHuntington.

Tanya Huntington is a contributing writer at Literal. Follow her on Twitter at @TanyaHuntington.

Posted: April 4, 2012 at 4:33 am