Target in the NIGHT

Ricardo Piglia

It was a cool Sunday afternoon. Men from the farms and estancias from throughout the district lined up against the fence that separated the track from the surrounding houses. A couple of boards were placed over a pair of sawhorses to set up a stand to sell empanadas, gin, and a coastal wine so strong it went to your head just by looking at it. The fire for the grill was already lit, there were racks of ribs nailed on a cross, and entrails stretched out on a tarp laid out on the grass. Everyone was gearing up as if for a big fiesta; there was a nervous, electrified murmuring through the crowd, typical of a long-awaited race. There were no women in sight, only males of all ages, boys and old men, young men and grown men, wearing their Sunday best. Laborers with embroidered shirts and vests; ranchers with suede jackets and scarves around their necks; young men from town with jeans and sweaters tied at their waists. Large numbers of people milling about. The betting started right away, the men holding bills in their hands, folded between their fingers, or behind the headbands of their hats.

A lot of men from out of town came to watch the race, too, and they were all gathered toward the end of the track, at the finish line, near the bluff. You could tell they weren’t from the area by how they moved, cautiously, with the uncertain step of someone not on home turf. The loudspeakers from the town’s advertisement company—Ads, auctions, and sales. The voice of the people—played music first, then asked for a round of applause for the judge of that afternoon’s race: Inspector Croce.

The Inspector arrived wearing a suit and a tie and a thin-brimmed hat. He was with Saldías the Scribe, who followed him around like a shadow. Some scattered applause sounded.

“Long live the Inspector’s horse!” a drunk yelled.

“Don’t get smart with me, Cholo, or I’ll throw you in jail for contempt,” the Inspector said. The drunk threw his hat in the air and shouted:

“Long live the police!”

Everyone laughed and the atmosphere eased up again. Croce and the Scribe very formally measured the distance of the track by counting the requisite number of steps. They also placed a linesman on either side, each holding a red towel to wave when everything was set.

During a break in the music, a car was heard driving up at full speed from behind the hill. Everyone saw Durán driving Old Man Belladona’s convertible coupe with both sisters beside him in the narrow front seat. Redheaded and beautiful, they looked as if they hadn’t gotten enough sleep. While Durán parked the car and helped the young ladies out, the Inspector stopped, turned around to look at them, and said something softly to Saldías. The Scribe shook his head. It was strange to see the sisters together except in extraordinary situations. And it was extraordinary to see them there at all because they were the only women at the race (except for the country women selling empanadas).

Durán and the twins found a place near the starting line. The young women each sat on a small, canvas folding chair. Tony stood behind them and greeted people he knew, and joined in making fun of the out-of-towners who had crowded together at the other end of the track. His thick, black hair, slicked back, shone with some kind of cream or oil that kept it in place. The sisters were all smiles, dressed alike, with flowery sundresses and white ribbons in their hair. Needless to say, had they not been the descendants of the town owner, they wouldn’t have been able to move about with so much ease among all the men there. They, the men, looked at the Belladona sisters out of the corner of their eyes with a combination of respect and longing. Durán was the one who’d return the looks, smiling, and the men from the countryside would turn around and walk away. The two sisters also immediately started betting, taking money out of a diminutive, leather purse that each carried around their shoulder. Sofía bet a lot of money on the town’s dapple grey, while Ada put together a stack of five-hundred and one-thousand bills and played it all on the sorrel from Luján. It was always like that, one against the other, like two cats in a bag fighting to get out.

“Fine, that’s fine,” Sofía said, and raised the stakes. “The loser pays for dinner at the Náutico.”

Durán laughed, joking with them. People saw him lean forward, between the two, and reach toward one of the sisters, and warmly tuck a rebellious strand behind an ear.

Then everything froze for an endless instant. The Inspector motionless in the middle of the field; the out-of-towners quiet as if asleep; the laborers studying the sand on the track with exaggerated attention; the ranchers looking displeased or surprised, surrounded by their foremen and farm hands; the loudspeakers silent; the man in charge of the grill with a knife in his hand suspended over the flames of the barbeque; Calesita the Madman circling slower and slower until he too stood still, barely rocking in place as if to imitate the swaying of the canopies over the carousel in the breeze. (Carousel: a word Tony taught Calesita one time when he stopped to speak with the town’s madman in the main square.) It was a remarkable moment. The sisters and Durán appeared to be the only ones who continued on, speaking softly, laughing, he still caressing one them, the other pulling on the sleeve of his jacket to get him to bend toward her and hear what she had to whisper in his ear. But if everything had stopped it was because, on the other side of the row of trees, the rancher from Luján—Cooke the Englishman—had shown up, tall and heavy as an oak. Next to him, swaying his hips as he walked with a studied smugness, his riding crop tucked under his arm, was the small jockey. Half yellowish-green from drinking so much mate, he looked at the men from the country with disdain because he had raced in the hippodromes in La Plata and San Isidro, and because he was a professional turf racer. The story had reached the town of how the jockey had lost his license when he jostled a rival coming out of a curve at full speed. The move apparently forced the other horse to roll, badly killing the jockey, crushed underneath the animal. People said that he spent time in jail at first, but was later released when he claimed that his horse was spooked by the whistle of a train pulling into the station in La Plata, directly behind the racetrack. People said that he was cruel and quarrelsome, that he was full of tricks and wiles, that he was responsible for two other deaths, that he was haughty, tiny, and mean as pepper. They called him el Chino because he was born in the District of Maldonado, in the Oriental Republic of Uruguay—but he was so cocky and arrogant, he didn’t seem like someone from Uruguay.

One-Eyed Ledesma’s dapple grey was ridden by Little Monkey Aguirre, a trainee of at most fifteen years who looked as if he’d been born on a horse. Black beret, scarf around his neck, espadrilles, baggy trousers, thick riding crop, Little Monkey. In front of him, the other jockey, diminutive, dressed in a colorful vest and jodhpurs, a glove on his left hand, his scornful eyes two wicked holes in a yellow plaster mask. They looked at each other without saying anything: el Chino with his crop under his arm and the black glove on his hand, like a claw, and Little Monkey kicking stones out of the way, as if he wanted to clear the ground, stubborn, fussy. His way of focusing before a race.

When everything was ready, they set about mounting their horses. Little Monkey took off his sandals and got on barefoot, putting his large toe through the rope of the saddle, Indian-style. El Chino used short stirrups, up high, English-style, half-standing on his horse, both reins in his gloved left hand, while he patted the horse’s head with his right and whispered in the horse’s ear in a distant, guttural tongue. Then they weighed them, one at a time, on a maize-weighing scale that lay flat on the ground. They had to add weight to Little Monkey; el Chino had about two kilos on him.

They decided the horses would take off with a running start and then race a distance of three blocks, barely three hundred meters, from the shadow of the casuarina trees to the embankment of the downhill slope, near the lake. One of the linesmen laid out a yellow sisal string at the starting line, which shone in the sun as if it were made of gold. The Inspector stepped to the line and waved his hat to indicate that everything was set. The music stopped, silence settled over everything again, the only sound the soft murmur of a handful of people placing the last few bets.

The racehorses took off in a trot from underneath the tree covering. There was one false start and two different attempts to get the horses lined up again. Finally, they came running up from the back in a light gallop, perfectly even, picking up speed, expertly mounted, nose to nose, and the Inspector clapped his hands loudly and shouted that it was a fair start. The dapple grey seemed to jump forward and right away took a head’s length lead over el Chino, who was riding draped over his horse’s ears, without touching him, his whip still under his arm. Little Monkey came up whipping his animal wildly. Both ran as fast as a light.

The loud cheers and insults formed a chorus that surrounded the track. Little Monkey led for the first two hundred meters, at which point el Chino started hitting his sorrel and quickly closed in on him. They raced to the end, neck and neck. When they crossed the finish line Ledesma’s dapple grey had a nose on the sorrel from Luján.

El Chino jumped off of his horse, furious, and immediately shouted that it had been a false start.

“The start was fair,” the Inspector said, unfazed. “Little Monkey won, at the finish line.”

A ruckus started up. Amid the confusion, el Chino started arguing with Payo Ledesma, owner of the winning horse. First he insulted him, then he tried to hit him. Ledesma, who was thin and tall, put his hand on el Chino’s head and kept him at an arm’s length, while the small, enraged jockey kicked and swung him arms in vain. Finally, the Inspector intervened. He yelled until el Chino calmed down, dusted himself off, and turned toward Croce.

“I get it. The horse is yours, right?” el Chino asked. “No one in this town beats the Inspector’s horse, is that it?”

“Inspector’s horse my ass,” Croce said. “You jockeys. When you win everything’s fine and dandy, but when you lose the first thing you do is claim that the race was fixed.”

Feelings ran high, everyone was arguing. The bets hadn’t been paid yet. The sisters stood up on their small canvas seats to see what was going on. They balanced themselves by each holding on to one of Durán’s shoulders. Tony stood between them, smiling. The rancher from Luján seemed very calm, holding his horse by its bridle.

“Relax, Chino,” he said to his jockey, and turned to Ledesma. “The start wasn’t clear. My horse was cut off and you,” he said, looking at Croce, who had lit a small cigar and was smoking furiously, “you saw it and still gave the sign for a fair start.”

“In that case, why didn’t you speak up earlier and say that it was a false start?” Ledesma asked.

“Because I’m a gentleman. If you claim that you won, that’s your business, I’ll pay the bets. But my horse is still undefeated.”

“I disagree,” the jockey said. “A horse has his honor, he never accepts an unfair defeat.”

“That little doll-man is crazy,” Ada said, with astonishment and admiration. “Really stubborn.”

As if he could hear them all the way from the other end of the field, el Chino looked at the twins up and down with audacity, first at one and then the other. He turned to face them, insolent and vain. Ada raised her hand and formed the letter c with her thumb and index finger, smiling, to indicate the small difference by which he had lost.

“That little guy is all cocked and ready to crow,” Ada said. “I’ve never been with a jockey,” Sofía said. The jockey looked at both of them, bowed almost imperceptibly, and swayed away, as if one of his legs was shorter than the other. His whip under his arm, his little body harmonious and stiff, he walked to the pump by the side of the house and wetted his hair down. While he was pumping the water, he looked at Little Monkey, sitting under a tree nearby.

“You beat me to it,” he said.

“You talk too much,” Little Monkey said, and they faced each other again. But it didn’t go any further than that because el Chino walked away. He went to the sorrel and spoke to him, petting him, as if he were trying to calm the horse down, when he was the one who was upset.

“I’ll say it’s ok, then,” the rancher from Luján said. “But I didn’t lose. Pay the bets, go on.” He looked at Ledesma. “We’ll go again whenever you want, just find me a neutral field. There are races in Cañuelas next month, if you want.”

“I thank you,” Ledesma said.

But Ledesma didn’t accept the rematch and they never raced again. They say the sisters tried to convince Old Man Belladona to buy the horse from Luján, including the jockey, because they wanted the race to be restaged, and that the Old Man refused—but those are only stories and conjectures.

March arrived and the sisters stopped going swimming at the pool in the Náutico. After this, Durán would wait for them at the bar of the hotel, or he’d say goodbye to them at the edge of town and walk to the lake, making a stop at Madariaga’s Tavern to have a gin. He was seen at the bar of the hotel almost every night, he kept up a tone of immediate confidence, of natural sympathy, but slowly he started growing more isolated. That’s when the versions of his motives for coming to town started changing, people would say that they’d seen him, or that he’d been seen, that he’d said something to them, or that someone had said something—and they’d lower their voices. He looked erratic, distracted, and he seemed comfortable only in the company of Yoshio, while the latter appeared to become his personal assistant, his cicerone and his guide. The Japanese night porter was leading him in an unexpected direction that no one entirely liked. They swam naked together in the lake during siesta time. Several times Yoshio was seen waiting for Durán on the edge of the water with a towel, and then drying Tony vigorously before serving him his afternoon snack on a tablecloth stretched out under the willows.

Sometimes they’d go out at dawn and fish at the lake, rent a boat and watch the sunrise as they cast their lines. Tony was born on an island in the Caribbean, and the interconnected lakes in the south of the province, with their peaceful banks and their islets with grazing cows, made him laugh. Still, he liked the empty landscape of the plains, beyond the gentle current of the water lapping on the reeds, as they saw it from the boat. Expanding fields, sunburnt grass, and occasionally a water spring between the groves and the roads.

By then the story had changed. No longer a Don Juan, no longer a fortune seeker who had come after two South American heiresses, he was now a new kind of traveler, an adventurer who trafficked in dirty money, a neutral smuggler who snuck dollars through customs using his North American passport and his elegant looks. He had a split personality, two faces, two backgrounds. It was impossible to reconcile the versions because the other, secret life attributed to him was always new and surprising. A seductive foreigner, an extrovert who revealed everything, but also a mysterious man with a dark side who fell for the Belladona sisters and got lost in the whirlwind that followed.

The whole town participated in fine-tuning and improving the stories. The motives and the point of view changed, but not the character. The events themselves hadn’t actually changed, only how they were being perceived. There were no new facts, only different interpretations.

“But that’s not why they killed him,” Madariaga said, and looked at the Inspector again in the mirror. Nervous, his riding crop in his hand, Croce was still pacing from one end of the tavern to the other.

The last light from the late March afternoon seeped in, sliced by the window grilles. Outside, the stretched-out fields dissolved like water in the dusk.

They spoke from late afternoon until midnight, sitting on the wicker chairs on the porch facing the back gardens. Every so often Sofía would get up and go into the house to refresh the ice or get another bottle of white wine, still talking from the kitchen, or as she went in or out the glass door, or when she leaned on the railing of the porch, before sitting down again, showing off her suntanned thighs, her bare feet in sandals with her red-painted toes—her long legs, fine ankles, perfect knees—which Emilio Renzi looked at in a daze as he followed the girl’s serious and ironic voice, coming and going in the evening—like a tune—only occasionally interrupting her with a comment, or to write a few words or a line in his black notebook, like someone who wakes up in the middle of the night and turns on a light to record on any available piece of paper a detail from a dream they have just had with the hope of remembering it in its entirety the next day.

Sofía had realized long ago that her family’s story seemed to belong to everyone, as if it were a mystery that the whole town knew and told over and over again, without ever managing to completely decipher. She had never worried about the different versions and alterations, because the various stories formed part of the myth that she and her sister, the Antigones (or was it the Iphigenias?) of the legend didn’t need to clarify—“to lower themselves to clarify,” as she said. But now, after the crime, amid all the confusion, it might be necessary to attempt to reconstruct—“or understand”—what had happened. Family stories are all alike, she said, the characters always repeat—there is always a reckless uncle; a woman in love who ends up a spinster; there is always someone who is mad, a recovering alcoholic, a cousin who likes to wear women’s clothing at parties; someone who fails, someone who succeeds; a suicide—but in this case what complicated everything was that their family story was superimposed with the story of the town.

“My grandfather founded the town,” she said disdainfully. “There was nothing here when he arrived, just the empty land. The English built the train station and put him in charge.”

Her grandfather was born in Italy and studied engineering and was a railroad technician, and when he arrived in Argentina they brought him out to the deserted plains and put him at the head of a branch line, a stop—a railroad crossing, really—in the middle of the pampas.

“And now sometimes I think,” she said later, “that if my grandfather hadn’t left Turin, Tony wouldn’t have died. Or even if we hadn’t met him in Atlantic City, or if he had stayed with his grandparents in Río Piedras, then they wouldn’t have killed him. What do you call that?”

“It’s called life,” Renzi said.

“Pshaw8!” she said. “Don’t be so corny. What’s wrong with you? They picked him out on purpose and killed him, on the exact day, at the exact hour. They didn’t have that many opportunities. Don’t you understand? You don’t get that many chances to kill a man like that.”

***

*This is an excerpt from Target in the Night, forthcoming from Deep Vellum Publishing in November 2015. It was translated by Sergio Waisman*

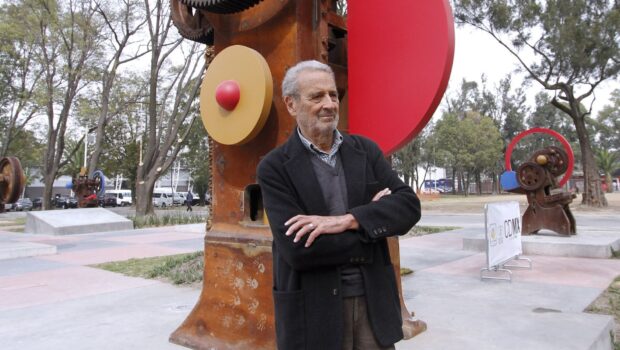

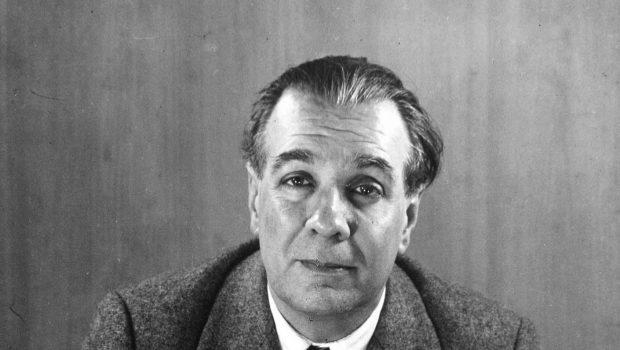

Ricardo Piglia is one of the most prominent authors of the entire Spanish-language world. His fiction grapples with the meaning of social and political processes. Two of his books have inspired films. His novel La ciudad ausente was adapted for opera. He received innumerable prizes for his works and for his lifetime’s body of literature. A literary critic, essayist, and professor, Piglia taught for several decades at American universities, including at Princeton for fifteen years.

Ricardo Piglia is one of the most prominent authors of the entire Spanish-language world. His fiction grapples with the meaning of social and political processes. Two of his books have inspired films. His novel La ciudad ausente was adapted for opera. He received innumerable prizes for his works and for his lifetime’s body of literature. A literary critic, essayist, and professor, Piglia taught for several decades at American universities, including at Princeton for fifteen years.

Sergio Waisman is the author of Borges and Translation: The Irreverence of the Periphery and of the novel, Leaving. Waisman has translated six books of Latin American literature.

Posted: May 31, 2015 at 9:55 pm