The Book of Eve

Greg Walklin

*The Book of Eve by Carmen Boullosa. Translated by Samantha Schnee

If read closely, the Book of Genesis is very strange. Light and darkness, as well as night and day, arrive before the stars. Woman is created via a rib from man, even though that, of course, is not how anyone has been born. A snake talks. And oddly, knowledge is presented as an enemy—a reason that humanity fell out of divine favor.

Of course, Genesis is not, and was not meant to be, literal history; but in between all of these lines, we can detect subtextual meaning. As Claude Lévi-Strauss put it: “Myths get thought into man unbeknownst to him.” Less important in any creation myth is the lack of scientific knowledge; more important are the hints of ancient cultural norms and attitudes. By virtue of that story sticking around and maintaining importance in Judaism—and eventually in Christianity, too—it’s obvious that such norms continue to have currency in the western world.

The Book of Eve, a work of fiction by Carmen Boullosa, is cognizant of the cultural encoding in the Book of Genesis, and particularly the way it has served the interests of men. We can’t be sure who exactly wrote the creation stories in the Bible, for example, but we can be fairly sure that it wasn’t a woman. This novel thus aims at reversing the binary: at upending all of the encoded norms and themes that go along with it. Especially the patriarchal ones.

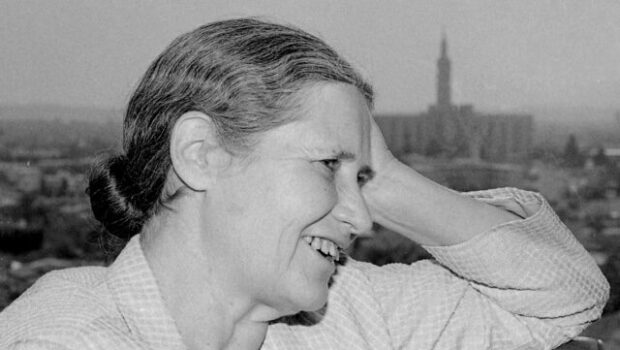

Boullosa, who was born in Mexico City, has a vast portfolio of work under her, including 18 novels, as well as many books of poetry. Her oeuvre has covered all kinds of stories, characters, and narrators, but has always turned her keen eyes on gender roles. Her rewriting of Genesis may have only been a matter of time.

In Boullosa’s telling, Eve, and not Adam, is the first. “Before me,” she announces early on, “Chaos and Eternity.” Everything begins with her: “I have no past. I was born of no one. I had no childhood. I’m the being that never dies. The first. The mother of you all.” Eden, meanwhile, is far from paradisaical. It is “a confined, restricted space,” and “an abstract plaything, a place where time did not exist, no night, no seasons, no rain, no wind, no drought, no cold, no distance; it was one dimensional.” “Thunder,” an abstraction resembling divinity, takes the place of God. As in the Bible, Eve and Adam are cast out of Eden after she eats the forbidden fruit, but it’s this event that really kick starts the narrative rather than ending it. Eve realizes the knowledge provided by the tree was essential, not damning: “The tree had helped me hear the ridiculous lies my ears had been ignoring.” There are wild beasts, amorous angels, giants, and things that, while often forgotten, do actually appear in various forms in the Pentateuch.

Boullosa also takes an alternative approach to Cain and Abel. In her telling, Cain is not the villain; Abel is in fact the criminal, after he and Adam rape Eve’s daughter. After the attack, animosity grows between the humans. Adam starts concocting lies about their beginnings, spinning yarns of Yahweh and placing himself at the center:

“Adam mumbles away in his sleep, repeating tales he hadn’t tired of telling the four winds, without me having any idea what he was saying: ‘I was first, and Eve came from me. They made her from one of my ribs, she’s not as important, just the offshoot of a piece of me, an afterthought, worthless.’”

It’s this development that both propels and hinders the book. While its approach is striking and innovative, The Book of Eve sometimes suffers from from a lack of nuance. Adam, the book’s villain, is a flat, cartoonish character of ego and violence. The narrative would have been better served with more firmly grounding his lies, turns to storytelling, and religiosity, in some kind of clearer foundation. The violence he resorts to comes out of nowhere. This blunts the book’s emotional impact, and the heroism of Eve.

If Adam is flat, Eve, meanwhile, is fully-formed, patient and saintly. Instead of sympathizing with Eve, we’re left puzzling over Adam’s bizarre behavior and almost comical misogyny. This could have been done in a different way, and not in a way that makes Adam sympathetic—indeed, his hatred and the conflict it creates is what really drives the story forward—but more organically. One wonders if it was Boullosa’s deeper intention to create a counter-narrative to Adam’s (i.e., the Bible’s) that also had its biases.

There is perhaps some supportive evidence for such intention. Interspersed with the chapters charting Eve’s course out of Eden and through the rest of the world are a number of “papers,” which include alternative narratives and retelling of some stories with different occurrences. This reflects controversies in the Biblical world, and the notion that the scriptures of Christianity (or any other religion) are only considered scriptures because a man, or group of men, decided they were the most authoritative. Although the book could have been strengthened, and given more layers, by having this stories tend to contradict the main narrative in ways that would have added layers of ambiguity, the point of “The Book of Eve” seems more polemical. (A biting forward attacking Eve and the papers, is particularly clever start.)

Overall, Boullosa has managed a tone both literary and Biblical, which is not terribly easy to accomplish, especially with a first person narrative (the “papers” sound even more like Biblical passages, which seems intentional). Kudos, also, to Samantha Schnee’s translation, which obviously plays an important part in the tone. There are, however, some minor infelicities that should be noted, as they can be jarring. For example, “cadavers” is used to describe the dead bodies of animals being eaten, but with that word’s medical connotations in English, this seems to have been an odd choice. A usage of “sweetie” in another part of the book feels anachronistic.

Because the accepted Biblical stories have held such a long sway over Western culture, counter narratives to accepted Biblical history continue to fascinate. (Indeed, there was even a “Gospel of Eve,” now only known in quotations, although it apparently was involved in more earthy questions.) “The Book of Eve,” like a lot of good literature, asks us to reconsider the norms and the hierarchies that have governed certain aspects of our lives. Though sometimes heavy-handed, this it definitely achieves.

Carmen Boullosa (Mexico 1954) is a leading Mexican poet, novelist and playwright. She has authored more than 30 titles, Antes (novel), La salvaja, and Papeles irresponsables, among others. She received the Xavier Villaurrutia in 1989.She currently teaches at Georgetown University, Washington D.C.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. His Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. His Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: April 27, 2023 at 10:22 pm