Cross Stitch

Greg Walklin

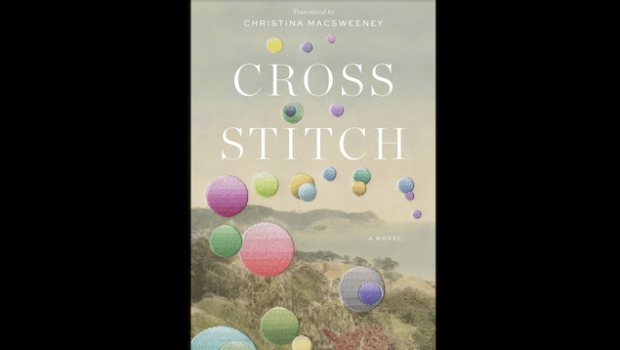

Cross Stitch

Jazmina Berrerra

Translated by Christina Macsweeney

In English, “text,” or the written word, and “textile,” or a piece of fabric, both originate from the Latin verb texere, which means to weave or plait together. Writing and weaving, combining thoughts and combining fabrics, are closely linked in our collective imaginations. Etymology rarely lies.

This connection is one of many insights found in “Cross Stitch,” the first novel by Jazmina Berrera, translated into English by Christina MacSweeney. Berrera, a Mexican author, has penned two other books of nonfiction, and while “Cross Stitch” has a discursive, somber tale about female friends at its core, it also features many gnomic vignettes about sewing and embroidery and the place it takes in culture.

As the book begins, Mila is a writer and mother of a small child, who receives a shocking bit of news: her friend, Citlali, has drowned. She wonders if it was accidental or if it was suicide, and reminisces about their past and friendship, which also included their mutual friend, Dalia. Mila narrates the novel in a smart, dispassionate manner, skipping around in time, from school days to summer volunteering to a European trip.

The girls used to be “inseparable,” Mila writes. “[We] had our own way of saying things, spoke with the same lexicon and the same intonation; it was the closest I’ve ever been to experiencing telepathy.” The Mexico they grow up in is dominated by lecherous men, especially those in power, who are constantly trying to use their positions for sexual gain. The novel’s crux dramatizes what happens during a long trip to England and France, which Mila and Dalia take to meet up with Citlali, who is then living in Paris. But even by the time they travel, their friendship has already fractured, and the women seem to be coming apart. When they are in Paris, for example, Dalia goes to Proust’s tomb, while Mila opts instead for Oscar Wilde’s.

Both Dalia and Citlali are mercurial figures. Citlali’s mother died when she was young, and she has a fractured relationship with her father who, Dalia and Mila suspect, abused her physically or sexually. Citlali dodges kisses, “which she’d do all kinds of maneuvers to avoid, preferring just to shake hands with people.” She has a strong phobia around needles. Mila’s middle school principal calls Citlali one of the “rotten apples” and discourages Mila from associating with her. Though she was supposed to meet up with Mila and Dalia in London, Citlali demurs for vague reasons.

Dalia, meanwhile, is brilliant and erudite, but appears to always be drifting existentially. Mila is in awe of her friend: “Very few of the things said to me in those years had as much effect as Dalia informing me that she liked my nose.” But Dalia “would go with anyone at all out of sheer boredom, because nothing and nobody ever satisfied her, and our friendship was almost certainly less important to her than it was to me.”

Berrera manages to make Dalia both fascinating and maddening, just like she seems to be to Mila. (“I wanted to emulate her,” Mila writes, “see what it felt like to be so electrifying, if only for a moment.”) Citlali, meanwhile, she leaves mysterious and somewhat vague. Because this is not a plot-focused or plot-driven novel, rather dwelling intensely on its characters, it’s mostly the curiosity about these two characters that has to drive the book forward. Despite knowing them for a long time, Mila still does not have a good grasp on some fundamental things about her friends.

Berrera, a native of Mexico City, has authored four books in Spanish: Cuerpo extraño, Cuaderno de faros, Linea nigra, and a children’s book, Los nombres de los animales and Punto de cruz. Cross Stitch is her first work to be translated into English by the venerable MacSweeney, who also translated Valeria Luiselli. The prose is even and neat. Mila’s writing “has a very similar rhythm to embroidery” one character tells her, and the same can probably said for the author’s. The sentences are sharp, succinct, and straightforward, rendered ably by MacSweeney’s lucid translation.

Although the characters are engaging, the story’s lack of drama slows the book down a bit. And in fact, it’s often the nonfiction elements on embroidery throughout this book—poetic sections set off by small images of a needle and thread—that perhaps constitute its most interesting and insightful parts. Sewing, importantly, has been both a punishment and a refuse for women, but it’s also been a reliable way of understanding the stories we read (on further thought, perhaps those too are connected). Weaving metaphors are common in criticism, such as referring to a novel plots as “threads,” or using “patchwork” or “stitch” to compare various parts. This reviewer has done this, definitely unthinkingly, many times.

Mila herself notes how so many bits of advice on improving needlework can actually be applied to writing, further highlighting the connection between the two: “Don’t pull the thread too tightly; if you do, the loop becomes narrow and the effect is lost.” And: “Do exactly the same but in mirror image, reducing by one line at each step.” And: “When you stop embroidering, the work should be taken from the frame to allow the clothe to breathe.” It’s a credit to the author that, obviously, this advice has been taken to heart. “Cross Stitch” is a fine and understated novel because it follows its own suggestions.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. His Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. His Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: January 28, 2024 at 9:52 pm