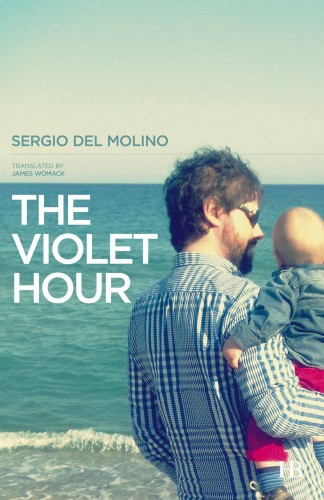

The Violet Hour

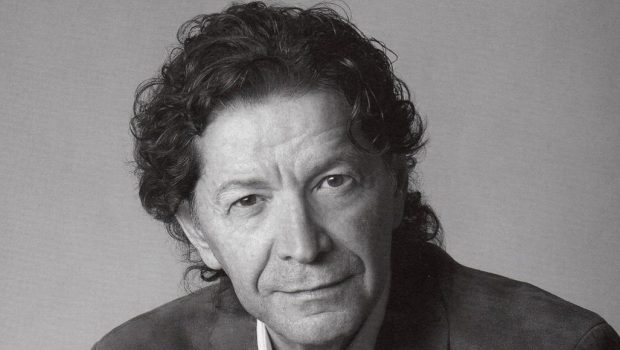

Sergio del Molino

Translated by James Womack

The doctors don’t know if Pablo was born with the disease or if he contracted it later. Sometimes I have the impression that they barely know anything. It is this ignorance that opens up a gateway to speculation, prayer, and quackery. Magical thinking can easily slip into this part of my life, where all I want is science, method, reason, and analysis.

Magical thinking is everywhere. Susan Sontag says that illness is filled with metaphors, and that in sickness the best way to remain sane is to ignore or destroy them. Metaphor is a form of understanding. Its literary function is to say more than linear and explicit language is capable of doing. Metaphor probes realities that normal use of language cannot understand or penetrate. But there is a perverse use of metaphor, the type that ends up hiding the nature of its object, filling it with strange connotations. Cancer has been covered with a large number of metaphorical layers that make understanding it almost impossible. Not understanding it medically, but socially, the level on which the people who suffer from it, as well as those of us suffering along with them, experience it. Sontag wrote this in 1978, when cancer was almost a taboo. Thirty years later, many of those metaphors are now meaningless, but there are a lot of clichés surrounding the topic and a strong general desire to hide what is ugliest about the disease. A triumphalist discourse, one which few doctors have the courage to present in more nuanced terms, speaks of cancer as something that will shortly be cured. Every small step forward is presented as an epic victory in a long and bloody war in which we believe the final victory will be ours (warfare is the most recurrent metaphor, used practically as an allegory). Although the truth is that we have been announcing an imminent cure for more than a century, and it has never come. The enemy will not be defeated, but we pretend not to realize that.

If the military metaphor is correct, then we are like Hitler in the spring of 1945, with the Russians at the gates of Berlin. Hitler gathered his general staff together and planned fantastic strategies using troops that had already been defeated, or who were fleeing like lame ducks, or who quite simply had never existed. The generals looked at one another, without daring to contradict the orders the Führer had laid out over the map of a Germany that had disappeared, the map of a fictitious country, a fantastical Europe that existed only in Hitler’s brain. The generals are the oncologists, shrugging their shoulders in the face of every new promise of victory. They know the truth that others keep hidden behind the cheerful statistical tables with their bright colors, hopeful and lively—red rather than blue, lovers’ flowers rather than flowers for funerals—and they know that there is not as much hope as one might expect hidden behind these numbers.

The delirium of a defeated Hitler exists side by side with the taboo, the crossed fingers, the iconography inherited from tuberculosis. It is difficult not to think about The Magic Mountain when you spend so much time on the pediatric oncology ward. In the sanatorium in Thomas Mann’s novel, the corpses of the consumptives who die in the night are removed via a discreet door, in covered sledges that go down into the valley under cover of darkness. The myth of the nighttime sledges carrying corpses is a topic of obsession for the patients in Doctor Behrens’s clinic. No one has seen them, but they all know they exist. The only thing that gives them any notice of a death is the fact that, one morning, a companion of theirs will not be present at breakfast. They find out that he is too weak to come down to the dining hall, and his friends, if the doctor allows them to, go up and visit him in his bed. The next day, someone walks past the dying man’s room and finds the door open. Inside, a cleaning woman is putting new sheets on the bed and carefully mopping all the corners of the room. And that’s it. There are no announcements or obituaries or lamentations. The chair the sick man occupied in the dining room will soon be taken by a new patient, a melancholic Russian princess, perhaps, or a fat, irascible German banker, or an eccentric Italian artist, and no one will mention the man who has disappeared ever again.

This novel infects my first days in the hospital. I feel like Hans Castorp. All the books that I take to the hospital room seem to be called Ocean Steamships and are covered with a thin layer of coal dust.

The Pediatric Oncology ward is small. There are not many children who suffer from cancer, and they don’t need a floor all to themselves. All of the other units in the hospital have two hallways, with rooms on either side of the nurses’ station. Pediatric Oncology only has one hallway. The other is closed off by opaque glass doors with signs prohibiting access to non-authorized personnel. A set of hospital rooms forbidden to the public. We look at them worriedly, trying not to get too close to the doors. One afternoon, Cris dares to say—I think those are the rooms where they take the children who are going to die. I think the same, but I hadn’t wanted to tell her. Through those doors is where Doctor Behrens’s sledges are parked, out of our sight, so as not to upset those of us who still believe our children will get better. The camouflaged trapdoor down to the morgue, so that we don’t see the covered sledges heading down into the valley in the middle of the night.

Early some mornings, when I leave the room to go and get a drink of water or stretch my legs a little, I take advantage of the silence and the solitude to open the cursed door a little. I see a hallway that is identical to our own, but with lots of lockers on the wall opposite the side that the rooms are on (which are otherwise identical to all the rest of the doors in the hospital). There are no secret passages, or coffins propped up in the corners, or parents crying on the floor. I don’t spend much time on my inspection, I’m scared of being found out, and I go back to Pablo’s bedside just as curious as I left it.

I don’t know how we find out one day just how ridiculous our fantasies are. Maybe the nurses tell us themselves, or else it is just our growing knowledge of the ins and outs of the hospital that reveals it to us. The rooms along that hallway are the ones used by the doctors on call during the night to sleep and change their clothes. It’s no more than that, a functional, aseptic zone, an area set aside for rest, taking advantage of the fact that children with cancer don’t need much space.

Neither Cris nor I manage to escape from the literary idea of tuberculosis, which is transferred almost in its entirety to the new idea of cancer. And we laugh about our fears and about how we still think like people who are healthy, when we need to start thinking like people who are sick, safe from taboos and metaphors. But it’s not so easy to ignore them. We still have a few disillusionments ahead of us before we are freed once and for all from the charms of magical thinking.

[…]

My son, what’s hurting, what can I do? You’re breathing and sweating in your crib with your eyes wide open, looking at something that isn’t there, concentrating on your pain. Like a wounded animal in the forest, I say to myself. I can almost smell the carpet of pine needles under your face, and the resin, and hear the cicadas and see the sun filtering through the branches. And you are there, lying down, like a wild boar with a spear wound, waiting for the dogs to arrive, that impertinent greyhound that will sniff you to see if you’re still alive. Your face against the pine needles, the forest vanishing into your body. Wounded animal, my son. Wounded animal, Pablo.

Wounded and scared, because you understand nothing. How can I explain it to you? How can I give you back your child’s eyes, your smile, your sweet, calm breathing? My fingers in your long hair, your blond hair, your smooth hair. I smooth and then rumple your hair with my slim fingers that know no other craft than that of writing, and I want the pads of my fingers to calm you and to take that wounded animal look from your eyes. Close your eyes, my darling. Rest and sleep a little, don’t try to keep on looking at something that isn’t there. Rest, I’ll keep the greyhounds away. No dog will sniff at you. No one will disturb your pain.

[…]

At the time of the first anniversary of the attacks of March 11, 2004, in which nearly two hundred people were killed in Madrid, my newspaper gave me a series of special assignments. Basically, what I was asked to do was to find the relatives of the victims from Aragon—officially there were three of them—and tell their stories for an anniversary supplement. The press had not spoken to them since the attacks, they had given the names of the victims, released a couple of photographs of the funerals, and a few biographical details were included in the police reports. I was to be the first person to trespass on their mourning.

Two of the three families refused to take part in my report. One was the family of a soldier, and the other, that of a woman from Ateca who had lived in Alcalá de Henares. However, the third family accepted, through gritted teeth. No one was more surprised than I. They were the parents of a nineteen-year-old, a student at the National Institute of Physical Education. A good-natured sportsman and a big fan of his home village, Alfambra, in the province of Teruel, where his family had opened a rural guesthouse. The young man was on his way to class and caught one of the trains that was then blown up.

His parents lived in a house in Coslada, and that’s where I went, taking the local train, the opposite route from that taken by their son on March 11, 2004. I went into their house, kissed the mother on both cheeks, and shook the father’s limp hand. I immediately perceived a cool hostility toward me, which I accepted as my due. The whole house was filled with the memory of their dead son. A huge portrait, the same one that would be used a few days later to illustrate my article in the special supplement, presided over the living room. Sports trophies, books, photographs. The absence of their son filled everything. The house was the event horizon of a black hole, antimatter. The vacuum, absorbing reality.

So, what do you want to know?

What did I want to know, I asked myself in the face of the apathetic gaze of this thin, sad couple. What did I want to know? Sitting in that room with two victims of terrorism, choking on the death that filled the air. If I had any scrap of dignity, I told myself, I would stand up, apologize, and leave. But submissiveness to one’s job generates a great number of excuses. Mine in this case was that I was there to tell the story as kindly and as subtly as the parents deserved, so that they wouldn’t be violated by other, less scrupulous journalists. I, at least, would use lubricant, and whisper sweet words into their ears.

I don’t know how I managed to make the conversation run along a smooth and polished path, but little by little we ended up chatting naturally. I tried to remain both friendly and impassive at the same time, although the interview affected me greatly. This couple had thought so much about their pain, had spent so much time on their son and death, and had come so firmly to the conclusion that his loss was an absolute guarantee of their own death, as well, that I almost felt like I couldn’t breathe. Why were they speaking? Why were they telling me all this? Why did they want the readers of a newspaper to know about it? I asked them. Because other people cannot do this, they said, because we are stronger, and we are still able to speak, and this pain is something that needs to be reported.

Very late in the afternoon, when they were sunk in their pain, they said something that I underlined to use in the article: We are in the labyrinth of pain, and this means that we are alone. Pain is something that frightens other people, we make them scared. People move away from you, they don’t understand you, they want you to get over it, they want you to get back to being how you were. But you can’t, and you don’t know how to explain it, either. They don’t know what to say to you, they don’t know what to do to make you feel better, and they end up moving away from you. We end up alone in our labyrinth.

The husband offered to drive me to the train station, and when we got there, before I got out of the car, he said to me—This is where I saw him for the last time. I brought him to the station, I gave him a kiss and arranged to meet him that afternoon. I asked him to be careful, and he laughed and ran off so as not to miss the train. And that was that, I never saw him again.

I walked up and down the platform, dizzy and disgusted with myself. For all that I was intending to write a good article about these people, I couldn’t escape the feeling that I was sullying them. But I went back to the newspaper office, I wrote the story, and I published it. Someone congratulated me on it (or maybe they didn’t, I can’t remember), and as the days went by and no one called to complain, I relaxed. At least I hadn’t upset them, I told myself.

Then another anniversary of March 11 came around, the trials started up, and some editor or other suggested at a meeting that we go back over the topic. Didn’t Sergio write an article about this? He should write another one, see how things are going now. My boss came back from the meeting very upset and hauled me into her office. She looked like she had just had a good telling-off herself and that she was choosing to offload onto me so that the shit could carry on flowing down the pipes. She told me the plan. I did not look enthusiastic. Not only that, but I even dared to speak up. What’s the point in going back over the same story? I asked. It was very tough to write the story the first time, and I don’t think it’s necessary to go over the same ground again, I insisted. It was very hard for the family, as well.

You’ll have to get in touch with the families of the three victims again, she said, as if she hadn’t heard me.

I’ll call them if you want, but the last time, only one family wanted to speak. Not only do I think things won’t have changed, but also, most likely, the family that spoke to us last time is not going to be willing to do it again.

She looked at me with some disgust and said—Well, make them want to.

She got up and left.

All journalists are used to pressure, and they all have to have elastic waists and jaws that open very wide if they want to survive. I knew—from too much experience—that this was not a job for the prissy, and this was also not the first time I had been threatened, either implicitly or explicitly, from both inside and outside the company. And this wasn’t even the worst, or the least ethical, or the rudest. But I did feel that this was the most unpleasant. I’ve been in stickier situations before, ones that were much more complicated and more humiliating than this one, but never have I hurt so much. I’ve been there, in that house, with those people, I said to myself. I have seen the portrait of their son in the living room, not just printed in the paper like the rest of you. I’ve heard their words from their own lips, not sweetened and tamed by my prose, like the rest of you. I’ve looked them in the eyes, I’ve seen them cry, they took me to the place where they kissed their son for the last time. For me, this was not a double-page, five-column spread for the Sunday supplement.

What did Kapuscinski say? That this is no job for cynics? I think it is, that I’m the one who’s not right for it.

But I called them, apologizing for bothering them, clear in my mind that I would not insist if they said no, but to my surprise, they said yes. The same parents, of course. The other victims refused once again, as I had expected.

I went back to Coslada, that insipid, municipal suburb, and this time I went out for a stroll with the father, and drank coffee with him. It was all very friendly. He was still tired, he had retired and was clearly weak, although he said he was better than he had been. His resignation was more cheerful. He didn’t expect anything from his life, but he didn’t mind that he was alive. Finally, sitting together on a bench, he leant over to me and said, lowering his voice to a confidential whisper—Do you want to know why we said yes to the interview? I didn’t know if I did, but I said yes. Because we loved what you wrote, he said. It was so delicate, so clean, we felt that it portrayed us so well and that our son was so clearly present in your lines that we couldn’t refuse you anything. We’ve gotten calls from television stations, and from El País, as well, and we said no to all of them, because we’re very tired. But we couldn’t say no to you.

When I left them, I was at peace. My bosses will never feel the pain of looking into the eyes of a father whose son had died in an attack, and of doing so in the intimacy of his own house, not in a public forum or in a press conference. They don’t have to deal with all that. But they will also never feel the peace I felt when I heard those words. No prize will ever feel as sweet to me as the knowledge that, in spite of everything, I had done a good job, that not only had I not hurt anyone, but that my words had served to some degree as a balm.

[…]

Complete remission comes at the same time as the cold. Cold and winds that are reminiscent more of Saskatoon than of Zaragoza, which is indeed cold and windy, but not like this, not as extreme as they are this winter. They give us the results over the telephone. Clean. The medulla is clean, they say, and I imagine it spongy and elastic, like a thread of gel detergent. It smells of flowers and chemicals, and makes Pablo’s bald head shine, giving a ping like in ads for cleaning products. Clean, polished, splendid, and a little wild. Zero per cent, decontaminated, pure.

Like that slave whose job was to remind Julius Caesar that he was only a man, our conscience, that dense cloud that has clamped itself to the backs of our necks ever since the day of the diagnosis, lessens our happiness. Complete remission is not a cure, we tell ourselves. But it is a step toward one, we console ourselves, a vital step. We no longer know what to feel.

We strike down the happiness of grandparents, uncles, and aunts with blunt cruelty, as they seem to be declaring victory straight away, as if complete remission were the words of some druidic spell, or the supplication they made to the proper saint had worked and now nothing and no one could stop Pablo’s journey back to health. We don’t want to be surrounded by uncontrolled optimism, even if that’s how we ourselves feel from time to time. It’s better to be cautious. One battle doesn’t win a war, even if it may prove decisive. It’s only over when the enemy army raises the white flag. Those military metaphors, always so effective, always so near at hand when we want to imagine ourselves heroes.

Using these military similes, we stop being poor wretches and become warriors, combatants under the command of the bravest of all generals—Pablo, my dear, sweet Pablo, the last person one could ever imagine wearing a pair of cartridge belts, pistol at the ready, and camouflage paint on his face. Metaphors, once again, are our salvation, but they cannot fool us. They help us appear less miserable, but they don’t protect us from the pain we feel or cushion us against reality, which advances implacably, naked, without any literary tropes.

Doctors, and even medical professionals who help as much as they can (psychologists, social workers, and so forth), abuse the metaphor of war. Oncologists refer to chemotherapy as their artillery and explain the treatment and its effects as using a cannon to kill a fly. The psychologists advise us to keep up the fight, and other parents talk about resistance. They will not get the better of us, we say, as if we were citizens of some besieged town under assault from a phantasmal enemy.

It’s strange that this metaphor can be so successful and be used in so many different situations when there is no real enemy, when the enemy is not some invader from outside, but something growing inside my son, something that is my own son. Siddhartha Mukherjee, an American oncologist who won the Pulitzer Prize with a lucid, brilliant book called The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, states that from one point of view, cancer is a genetically improved version of ourselves. If the aim of every living organism is to survive and reproduce, through adaptation and predation, then cancerous cells are at an evolutionary peak, cells capable of surviving the death of the body that generates them. There are laboratories that have live samples of cancerous cells from people who died thirty years ago, samples that are still reproducing and replicating themselves and invading Petri dishes in lieu of having any flesh to devour. How can you defeat something that exists in order to be immortal, invincible? And what is more, and what is worse, how can you defeat an alleged enemy that does not arrive from anywhere external but rather is the very person it attacks? A general knows how to repel an outside attack. He organizes his defenses, tries to cut his enemy’s supply lines, attempts to push him out of his territory, surrounds him, bombards him, annihilates him. But this is more like an attack against oneself. All your destructive power employed against your own soldiers in the hope that, when all of them or nearly all of them are dead, the fifth column that is destroying your rearguard will die, as well. The hope is to build a new country, an unthreatened country, from the smoking ruins of whatever’s left. It’s insane. No one would think of fighting a battle under those conditions. But that’s what chemotherapy does. Because we know that it works, sometimes, and that it’s better to have a ruined, damaged land than no land at all to return to. All of us would rather have a sick child than a dead child. At least, I would.

In the end, even I found my own version of the military metaphor. No one can escape from it. Self-pity eventually conquers us. We prefer to see ourselves as Rambo rather than as some pitiable invalid (yes, my son is sick and I am not, but although it is not my bones that are hurting, my heart does ache, and he does not feel that pain, those burning cuts). Anything to deny the image that we see in the mirror. This creature with his tousled hair and the bags under his eyes is not me. I am an athlete, I am a hero, I am a fighter. If I fall, then it will be with my sword in my hand, not a bottle of antidepressants or a box of sleeping pills. Come on, just a little bit further, you can do it, champ. As if victory depended on bravery or the strength of one’s balls. As if our attitude could change the results of the analysis at all.

Perhaps under the influence of this military thinking that impregnates everything we say, I teach Pablo a new game inspired by the metaphor. It’s my job to keep things funny in the family. Cris provides affection and discipline, and I train the kid up for the big comic numbers. I’ve taught him to salute like a soldier. I say to him—Pablo! Atten-shun! And Pablo, with an exaggerated Pavlovian reflex, puts his right hand up to his forehead. He doesn’t salute quite as formally as a soldier would, he slaps his bald head with the palm of his hand, and then smiles in expectation of the applause that he knows he deserves. He always improves on what I teach him, he adds a personal touch, a little tenderness. He never copies me in every detail, he prefers, like all good actors, to bring a little bit of himself to the role.

Pablo! Atten-shun!

And there’s another little plap as his hand strikes his forehead. And he laughs once again, my bald little boy, and for a moment we manage to believe that we are immune to the attacks of this army we have never seen, as if there had been a truce, or we had been given a leave of absence. There are days when we don’t need to dress as soldiers, because we are happy and nothing can make us feel wretched again. Those are the days when we recognize ourselves in the mirror, without any shame or fear.

[…]

In July 2008, Doctor Jeremiah Goldstein, a pediatrician from Philadelphia, published a strange article in the Pediatric Journal of Hematology and Oncology, a prestigious medical journal dedicated to the publication of the latest advances in the fields of pediatric hematology and oncology. The text he delivered to the magazine, however, was not an academic article, and was not even written by him. The doctor from Philadelphia had merely compiled the material. It was a diary that his mother, Sonja Goldstein, had kept during the illness and after the death of her son David, who died at age two from a nephroblastoma. This happened in 1955, and if Jeremiah—who was born after his brother died, which latter event it was almost forbidden to mention in their family—convinced his mother to make these papers public, then it was because he believed they had some significant clinical relevance, in the sense that they could help specialists who deal with children with cancer to understand their family members better and improve both their own work and their relationship with them. But it was not simply the professional use to which these documents could be put that inspired doctor Goldstein to make public the story of his dead brother. His discovery of the document—for his mother only gave the diary to him to read more than fifty years after the events they describe had happened—had a devastating impact on him. I suspect he reinterpreted a large part of his life on the basis of this material. Perhaps he discovered the prime causes that led him to become a pediatrician. I’ve known several adolescents who’ve had cancer and have decided, with vocational obstinacy, to study medicine. It’s fairly common.

Sonja Goldstein’s diary on the illness and death of her son David is filled with emotional details and descriptions. It magisterially alternates its clear account of events with the concrete expression of the pain, the contradictions, the impotence, and the constant disorientation felt by a mother. A childhood cancer in 2010 is entirely different from one in 1955. In 1955, chemotherapy was unknown, it was only just beginning to be suggested as a theoretical possibility. There were no pediatric oncology units, and it would be hard to say that there were even such things as oncologists. The discipline was at that time dominated by surgeons who enthusiastically went about cutting out or mutilating anything that appeared cancerous, without ever understanding why tumors carried on reproducing after they’d been expunged (to tell the truth, today’s science isn’t able to reply to this question with any kind of rigor, either; the day they know the answer, then all kinds of cancer will be curable). In 1955, a diagnosis of cancer in a child was a death sentence with no possibility of appeal. Hospitals dedicated themselves to offering the best possible out of a range of horrible deaths, providing they were able to, which they weren’t always. Doctors hoping to try out some course of treatment were either ignored or accused of committing therapeutic cruelty toward dying children who could be given no more help than a blanket to wrap around them and a glass of warm milk. Children did not go to the clinic to get better but to die. This had nothing, absolutely nothing to do with what we experience at the beginning of the twenty-first century. But as I read the diary, I felt as if I were in Sonja Goldstein’s skin. And I believe that if Sonja Goldstein read these pages, then she would feel as if she were in my psoriasis-ridden skin. Because she, like I, started off by asking herself why she was writing. And again like I, she did not find a reason. In the preface to her notes (the original text can be found in July 2008’s Pediatric Journal of Hematology and Oncology, volume 30, number 7, page 482), Goldstein writes as follows: “In the past, I have frequently marveled at the appalling frankness and minute detail with which some writers described personal tragedies. There had seemed to me a violation of intimacy, which I found difficult to accept. During the past year, I believe I have come to comprehend what motivated such writing. As our own personal tragedy has intensified in its starkness, I have felt an ever-growing urge to set down on paper what has happened. It seems as though by reducing these experiences to pen and paper, I might achieve a cleansing of the soul, a purging of the emotions. Writing this short history of David is designed as counsel neither of hope nor of despair. Rather, it is an account of inexorable fact.”

Sonja Goldstein is a cultivated, sensitive woman, married to a well-known lawyer and raised among Jewish intellectuals from the East Coast of the United States. And perhaps it is for this reason that her testimony is so much more valuable, because she knew how to use words and tone in such a way that other parents would never be able to in a thousand years. She used words to summon up her son’s physical presence. Whether she kept them to herself or decided to publish them many years later does not affect the value of these words, for they are universal and give a name to a pain that crosses countries and generations.

There is not a single word in her diary that I wouldn’t be able to recognize as my own. She writes: “One of the hardest tasks I—and I believe Joe also—have ever faced, is to resume “normal” living. In the hospital, we lived in a private world. We existed in a kind of suspended animation, concerned with David’s day-to-day progress and, above all, not faced with other people.”

Returning to normal life is something I still haven’t learnt how to do, and which I think I’m actively resisting. I can create a fictional front to fool inattentive observers, but the truth is that I’m still living in the violet hour. Even since before Pablo died, since the moment when they told us that he would die and that the only thing left for us to do was to be with him until the end. I have still not finished that waiting period. I am suspended within it.

In Eliot’s poem, the violet hour is that part of the evening when secretaries are about to leave their offices at a run, heading toward the promise of a kiss, a dance, a dinner, a night when their desires will once again go unfulfilled. It is this, the tremor before the stampede, the instant in which we remove the mask we wear when facing the daily, bourgeois order and replace it with our carnival mask, the one that fits closer to our face, the one it’s worthwhile wearing. The violet hour is a taxi stopped at the rank with its motor running. The violet hour, in fact, does not exist except as a place of transit, an annoying yet necessary transition. No one lives in the violet hour—people run from it into real life, into normal life. I have to learn how to escape, but I have not yet found a way.

To tell the truth, I haven’t tried very hard.

© Sergio del Molino: The Violet Hour, Hispabooks Publishing, 2016.

Sergio del Molino (Madrid, 1979) is a Spanish writer and journalist who lives in Zaragoza. He has worked for almost ten years as a reporter in the Heraldo de Aragón. He has won the Premio de Literatura Joven del Gobierno de Aragón for fiction and his first novel was shortlisted for the Francisco Casavella Award in 2011 and was chosen as one of the best ten books of 2012 by the Spanish Booksellers Association.

Sergio del Molino (Madrid, 1979) is a Spanish writer and journalist who lives in Zaragoza. He has worked for almost ten years as a reporter in the Heraldo de Aragón. He has won the Premio de Literatura Joven del Gobierno de Aragón for fiction and his first novel was shortlisted for the Francisco Casavella Award in 2011 and was chosen as one of the best ten books of 2012 by the Spanish Booksellers Association.

Posted: March 28, 2016 at 10:41 pm