Winter’s Fury By Perla Suez

Greg Walklin

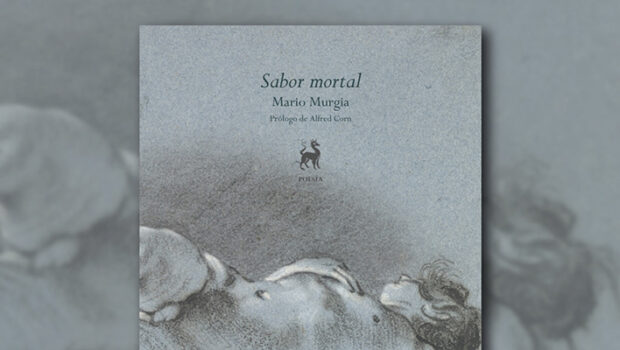

Winter´s Fury by Perla Suez. Translated by Rhonda Dahl Buchanan. (Literal Publishing, 2024)

When a terrorist act is committed, be it a bombing or a shooting or some other atrocious act of violence, there is an immediate public desire to know about the perpetrators. Why, we ask, was such an act of violence the answer? Competing with the need to know about a terrorist act is just as strong a desire to forget the perpetrator. Why, we also ask, should we give them any fame or recognition, when they were seeking this through such despicable means?

Perla Suez has written a short, elliptical novel, Winter’s Fury, about such an act of violence, and about an otherwise anonymous perpetrator of it, although she manages to mask it well. The book follows a man only ever called “Luque”—ostensibly his surname—who crosses over from Buenos Aires to Paraguay in 1979, during the some of the worst parts of Argentine dictatorship’s “disappeared” period. Suez only gives us a passing description of her main character: Luque is “tall and slender, with chestnut brown hair and a pointed nose”—otherwise, he is more of a shell or husk than a person, and it’s this gaping hole at the center of his being that is exploited by others throughout the story.

That’s not to say that Suez doesn’t add depth. Tragedy struck when Luque was still young: his mother became ill and died. His father did not take it well, first locking his son in his own bedroom, and then spiraling further into depression, eventually dressing up as his dead wife and committing suicide. Luque, in his shame, learned to deny his problems. (His father would tell him that “‘it was better to sleep to keep from thinking.’”) Luque’s wife, who left him before he left the country, didn’t provide much of a reason to him for wanting to go; although it doesn’t seem like any explanation would have sufficed. And his cousin, whom he meets in Asunción, at first doesn’t recognize him, but then says: “You haven’t changed a bit!” Luque seems to be barely there. Internalized shame and a significant lack of self-understanding has hollowed him out and made him apathetic and distant.

A few years after moving to Paraguay, Luque finds himself in Ciudad del Este, which is situated on the Paraná River near the borders with Argentina and Brazil. He falls into smuggling with a crooked police officer. When he first crossed the border, he told someone that he did “a little bit of everything,” but it’s only later that this comes true, and to chilling effect. Smuggling ends up being only one of Luque’s minor crimes.

Suez’s narrative glides along with Luque, succinctly and without frills, in part mirroring the way he views the world. In a lesser writer, this may have made for a boring tale, but Suez manages to make it engaging, as the unthinking Luque fall deeper into a life of crime. Her prose, here translated ably by Rhonda Dahl Buchanan, is generally flat and unadorned, which is reflective of its main character. The understatement works to great effect.

It would have been tempting, as a writer, to make Luque a sympathetic victim of everything he experiences, but Suez avoids this trope—he isn’t heroic in any sense. He bribes a man so he can start sleeping with his underage daughter, Isabel, and then grooms her to be his wife. He sees a boy fall into a river and does nothing to save him from drowning. But he also doesn’t intend to do some of the awful things he does, especially the worst actions, and is put in impossible positions where he is faced with a decision to sacrifice himself or save others. With no ideals, Luque never chooses sacrifice, and yet he doesn’t even seem to understand why.

Early on in the book, he has a symbolic dream of killing his double. Clearly, he is already trying to escape from himself, but, as the book shows, Luque lacks any ability to discern the shadows on the cave wall from reality itself. Only later, only after everything horrible happens, does something dawn on Luque as he is drinking coffee: “He took another sip, swallowed, and a long silence enveloped him. Something burned inside him, and for the first time he saw with absolute clarity that he was alone.” The only positive in this novel is that Luque has finally come to some clear idea of the negatives in his life.

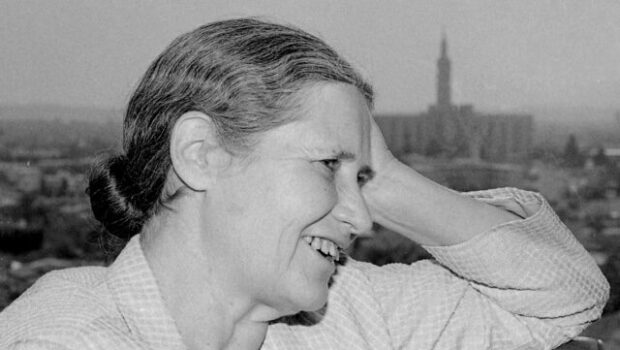

Suez is a recipient of the prestigious Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Literature Prize and Rómulo Gallegos International Prize, and has written numerous novels. “Furia del invierno “was first published in Spanish in 2019. Suez has a Guggenheim Fellowship, which she received for her novel “La pasajera” (also translated by Buchanan). Though you certainly might not think it reading “Winter’s Fury,” Suez has also written numerous children’s books.

The author is from Argentina, and though this novel takes place mostly in Paraguay, it is really about Argentina’s history through an outside—and refreshing—lens, culminating in a horrific act. In the wake of 9/11, a slew of books and films attempted to grapple with all angles of how such organized crime develops. Movies such as “Paradise Now” and “A Prophet” both examined how young men could be caught in a web of crime and terror. American fiction, meanwhile, engaged with the 9/11 terrorists so significantly there have even been books written just surveying fiction’s response (and that doesn’t include all of the books surrounding the victims or using the attacks as backdrops). The architects of those crimes were motivated by hatred, religion, and politics, convenient tools for manipulating the foot soldiers; Luque, not motivated by anything, was exploited by individuals far from the front lines.

With nothing in his head but the desire to run away, Luque is the perfect cipher for his criminal bosses. “The mere idea of returning to Buenos Aires,” Suez writes, “made him anxious, stirring up everything he’d tried to bury. He was determined to escape.” Yet he seems to have absconded from the frying pan and found the fire. Suez’s novel ably shows the immense dangers of unthinking, and gives a new twist to Socrates’ proclamation about the unexamined life. It may not be worth living, but it can be quite worth exploiting by those wishing to spread terror and hatred. The first step in any battle opposing such forces: take a moment to really think.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. His Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. His Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: May 28, 2024 at 10:00 pm