Into the Woods

So Mayer

Nanette is what I have been watching instead of new films this month. Or rather, even when I am watching new independent films–like Carla Simon’s Summer 1993 or Cláudia Priscilla & Kiko Goifman’s Bixa Travesty–I am thinking about them through the lens of Hannah Gadsby’s hour-long performance, in which she unpacks the power of storytelling and makes a clearing for new kinds of stories. Stories that hew close to selves we haven’t seen on screen before such as Simon’s delicately-observed autobiographical first feature following a child coming to terms with the loss of her mother and her mother’s alternative world, and Priscilla and Goifman documenting the story of Brazilian musician, spoken word artist and gendernaut Linn da Quebrada.

A stage show filmed for Netflix, Nanette is not a film. Except it is: it’s a story told by audiovisual means. It’s stand-up comedy that’s not stand-up comedy, as a third of the way through Gadsby tells us she’s giving up comedy. Gadsby keeps standing but her material, and its delivery, will floor you. Talking, early on, about getting feedback from an audience member, she notes it arrived “straight after a show–that is when my skin is at its thickest.” It’s funny, but it is also revelatory of her vulnerability, and the detour the show will take. It’s an impassioned performance that asks, precisely, how we keep going when we can no longer keep going. Far from donning a TimesUp pin on the red carpet, it truly calls time not just on individuals who perpetrate abusive behavior, but on the system that props them up. Including the system implanted in our minds about how stories are told, and whose stories count.

Like Nanette. Although Gadsby says at the start of her show that it’s named after a woman she met in a cafe in a small town in Australia, I wonder. Could the title be a reference to No, No, Nanette, a Broadway musical filmed twice (Clarence G. Badger, 1930 & Herbert Wilcox, 1940)? It’s the source of the song “Tea for Two” and Gadsby does note that her favorite sound is a tea cup finding its place on a saucer. But it’s also a story (not that this is how your classical movie guide would describe it) about a young woman who enables the exploitation of other young women by providing cover for her uncle, a millionaire Bible publisher/hypocrite while her own desire to be independent and single gets ground down. Gadsby’s show, with its swinging second half tearing white straight cismen a new one (as she puts it herself), could be called No (More) Nanette.

But Gadsby does not let herself off the hook: the pivot of the show is the story about why she’s giving up comedy, a story about how telling two particular stories – the story of coming out to her mother, the story of a confrontation with a homophobe at a bus stop–over and over as jokes has turned herself into a punchline. “Because,” she says, “do you understand that what self-deprecation means when it comes from somebody who already exists in the margins? It’s not humility, it’s humiliation.” When she retells the stories in full, you hear the ‘punch’ in punchline. And this is the show’s haunting power: it subtly recognizes that we “not-normals” been Nanette(d), conned into denying ourselves (no, no), both sacrificing ourselves and providing cover for patriarchal business as usual. That we need to evolve beyond victim narratives; beyond punch-lining ourselves in the face to keep the audience with us.

Gadsby initially uses the term “not-normals” in contrast to “gender-normals,” but as the show spins wider in its blistering address to dominance culture–and given that Gadsby has recently spoken about her diagnosis with autism spectrum disorder–the gender–remains present as but one axis or aspect of so-called normalcy. Advocating for multiple perspectives, Gadsby’s particular perspective welcomes many who feel excluded by dominance culture for multiple reasons.

So where do we not-normals go if we want to hear a different story? It’s a question that the mainstream film industry has been asking itself in earnest for nearly a year now, while ignoring the answers that already exist, with forty years of feminist film (not just theory, but practice) available to re-view and learn from. Nanette, as lesbian stand-up comedy (although Gadsby queries the term because she doesn’t do much lesbianing in daily life), is quietly conscious of four decades of lesbian and feminist one-woman shows that put under heard stories front and centre, and turned storytelling itself inside out. Their shows weren’t called comedy, because as Gadsby points out, women weren’t funny then; but Nanette has its antecedents in the work of the New York lesbian theatre WOW Cafe, where writers and performers like Lisa Kron wowed radical queer crowds . Kron, more recently, wrote the book for the musical Fun Home, the first Broadway musical with a lesbian protagonist. It won five Tony awards (among others), and is currently playing to sold-out houses in London, suggesting–along with Nanette’s global acclaim–that the “not-normals” are having a bit of a moment.

Not so much in that mainstream film industry, eh–although I’m looking forward to Desiree Akhavan’s Sundance-garlanded queer teen unrom-com The Miseducation of Cameron Post, we’re still talking indie. While the major-league gatekeepers are busy patting themselves on the back for remembering to celebrate Agnes Varda (now she’s seen as a kindly grandmother), there’s much less sign that anyone is paying attention to the radical lessons of her cinema. This summer has seen the re-release of two of her films: in France, One Sings, The Other Doesn’t, her 1977 folk-pop reproductive justice musical, which finds and creates comedy of an unromantic kind where there is usually only moralizing tragedy, in the story of two female friends’ self-determination about their bodies, and those of their children.It has a song with lyrics by Friedrich Engels. And they scan.

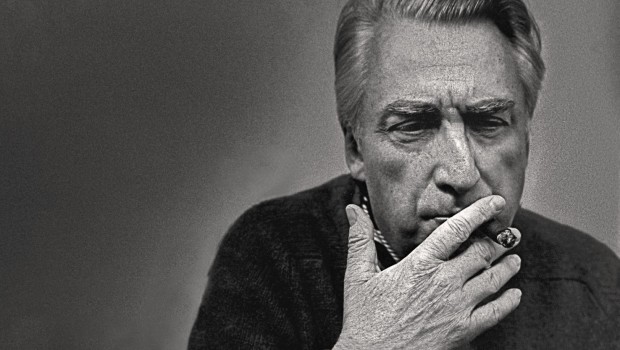

And in the UK, Varda’s later film Vagabond, where her joyful feminism had tipped over into anger, has been re-released. A blistering essay in thirteen non-linear chapters on the social costs of austerity and the violence of a capitalist society, Vagabond’s French title is Sans toit ni loi–without walls or rules. It follows a young woman who has changed her name to Mona, but who refuses absolutely the contract of the Mona Lisa: smile and be silent. To live entirely without bosses, boyfriends, or social structures, she is entirely reliant on herself, and she survives for a very long time with almost nothing. Like Gadsby, she survives sexual assault and gender-based violence after she is dropped off in the woods by a female professor of arboriculture, whose guilt over letting Mona go literally electrifies her.

Varda does not let herself, a middle-class artist with a settled life, off the hook. While she tells Mona’s story, she is not Mona: she knows she is just another one of the people who let Mona down and let her go. By association, she does not let us as viewers off the hook. We know from the start of the film that Mona is dead; at the very end she is still breathing, only just. What can we, film viewers, do to save her?

Nothing. Because it is a film. And because the Mona we care about and for on screen, we walk past every day of our lives.

“And this tension, it is yours. You need to learn what it feels like. Because this tension is what not-normals carry inside of them all the time, because it is dangerous to be different.”

That is Gadsby’s review of her own show, but it could also be her review of Vagabond. Because she and Mona both go to the same place: into the woods, and out of patriarchal histories. As Gadsby, who worked as a tree planter and delivers her set in front of huge, beautiful blue paintings of trees, tells us: “One of the things I can do is generate thoughts unprompted in my own brain… but art history taught me that women didn’t have time to think thoughts. They were too busy napping alone in the forest.” Although Gadsby and Mona both confront sexual violence (both physical and cultural) because of their difference and their search for a space to be different, there is something other than survival, or even than storytelling, that exceeds that violence. The tension they hand us; the need to enter with them, on their terms, into the tangled complexity of the real trees, not the charming pastoral that encodes the sexual violence of looking at (i.e. possessing) sleeping, naked women.

“I just don’t have the strength to take care of my story,” Gadsby concludes; that could be Mona’s conclusion, too, as she breathes, alone and soaked, into freezing stillness. As a film critic, I have to ask myself not only: do I have the strength to take care of her story? But: does cinema? Does our culture? Looking back over the histories I’m privileged to know and study, I see glimpses of hidden histories that I ache to share, but I wonder whether there can ever be more than this slender crack where the lesbian light is getting in, casting long, beautiful, grieving shadows, shadows that fall like trees; stories that have fallen in(to) silence for too long.

So Mayer is the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism and Documentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

So Mayer is the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism and Documentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

©Literal Publishing

Posted: August 9, 2018 at 10:19 pm