STAY AT HOME… WITH ALL YOUR PRIVILEGES

Quédese en casa…, con todos sus privilegios

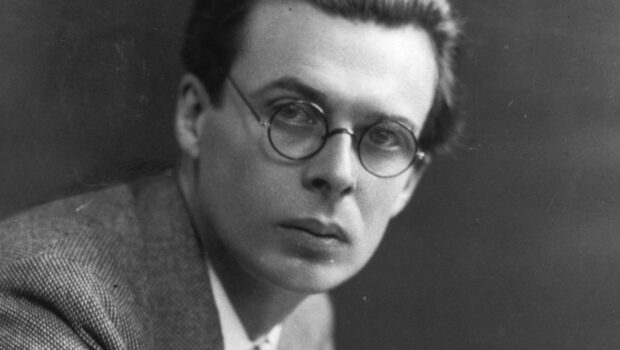

Alejandro Badillo

Translated from Spanish by Kelley D. Salas

One

They’re on social media, worrying about the environment and calling upon us to fulfill our responsibilities as citizens: don’t litter, don’t pollute, respect pedestrians, be kind to animals. They support the best causes, the ones that, on paper, no one can argue with, because they promote a better world: renewable energy, recycling, bike transportation, slow food. They’re committed to women’s rights and demand an immediate answer from the government on problems like violence, corruption, and street vendors. Sound familiar? Maybe you have several among your contacts on social media. Maybe you see yourself in this description because–let’s be honest–many of us use social media to complain about what’s wrong in the world, oftentimes more to vent than to demand an immediate result or start a social movement. But I’m talking about people who complain and who are part of a minority group, a group that can afford a lifestyle that the bulk of the population could never even dream of. This group of people, living in various places across the globe, has enormous advantages from birth and makes up an elite that, try as it might, can’t empathize with the reality of billions of people–a number that’s increasing due to coronavirus–because, to put it simply, they live in a different universe. These elites, who have only a superficial understanding of the emergency facing our climate and our society, feel they can legitimately demand changes to a system that sustains and benefits them, whether directly or indirectly. Of course, we’re not talking about a suicidal elite who want to abolish their privileges and march with the disinherited of the earth. These are people who suffer from a type of ignorance or blindness about their place in society. If the members of this group were polled or interviewed, we’d discover, surprisingly, that they view themselves as victims of the world they were born into; they’d likely describe innumerable calamities inflicted upon them by the government and other players who affect them. Incapable of owning their privileges or comparing their lives with the lives of ordinary people–those who risk exposure on public transport as they make long commutes to their jobs or who can barely make it from paycheck to paycheck because of their meager wages–they feel vulnerable and, above all, offended by the state of things. In this way, they appropriate the discourse of the nonconformists, of the rebels, of those who “think out of the box,” when in reality, their proclamations mean nothing because of their contradictory modus vivendi.

Two

The newspaper El País recently published an article with a title that was quite a mouthful: “The phenomenon of privileged quarantine posts on social media leads to Internet debate on social inequality.” The article, accompanied by photos and videos, describes the new trend among artists, business owners and socialites of showing off the luxurious interiors of their mansions while enjoying the coronavirus quarantine. Some are learning new skills, like cooking, while others spend their days serenely taking in the immense gardens around their homes. Of course, this hasn’t gone unnoticed by some Internet users who have criticized the fact that, while millions are losing their jobs or becoming severely ill because of the way they make their living, the twenty-first century influencers and the privileged are wondering on their blogs whether they should grill their salmon, or bake it.

Privileged people in quarantine, unable to boast about their foreign travel or their experiences living abroad, are showing off something more important–something they can enjoy in their mansions and something that’s very scarce for those condemned to inequality: time, peace, and quiet. These intangible goods, available for the taking for those at the top of the pyramid, are a pipe dream for food delivery people employed by Internet-based platforms that deny their workplace rights as they travel though streets rife with cars, pollution and danger. Enjoying a leisurely, quiet, sunset in a huge yard is an unknown luxury for someone who lives in a tiny house or apartment, for someone who has two or more jobs and barely has time to escape from reality for a couple of hours with the distraction of a soccer game or a movie on TV. From their luxurious retreats, the elite–in addition to the predictable complaints about coronavirus restrictions –are asking to do away with inequality, to reforest the land, take care of the water supply, support renewable energy and stop using fossil fuels that are burning up the planet. They also insist, through social media, on improving architecture in their cities, on building wide benches, redesigning parks and promoting inclusive urban planning. Who could argue with these ideas? No one. But when they come from a sector of the population that has accumulated its wealth by exploiting human and natural resources practically without limit, it’s an empty gesture, one that only the most gullible would believe. A true action step that would be within their grasp would be to assume the costs for their lifestyle, meaning: to examine the origins of their prosperity beyond their homes filled with solar panels, rain gardens, bikes for transportation and recycling. In doing that, they’d discover that inequality and unbridled consumerism are the true problem. If we don’t find a solution to inequality, and a fairer distribution of resources, the changes promoted by those at the top will be enjoyed by the same people who have been–and will continue to be–at the top. Sustainability and ecology will be luxury goods, as they already are in numerous cities, a utopia for people whose only hope is to struggle for their survival.

To change a system that has exploited the environment and entire generations of human beings, we must go beyond individualism and organize collectively. Absent that, so-called “social consciousness”–as much as we try to affirm it or demonstrate the contrary–will be a new label for “the good life.” A fight for social and ecological justice that comes from a place of privilege will be a placebo, or at best, a series of initiatives for the gated communities where the elite live. They’ll continue to pontificate from there, lecturing the stubborn folks who cause pollution in the streets and the uneducated who refuse to change their harmful ways. Of course, those who live on the margins of prosperity do have some responsibility, but the privileged ascribe to them the same capacity for action that they have, simply because they don’t know them and therefore, can’t imagine what their days are like. Can an employee who gets off work late at night and who lives far away from their workplace ride a bike to reduce pollution? Can a family that barely manages to stock its pantry with processed foods afford organic produce? Can people who lack drinking water be ecological and sustainable? Would they have taken classes on how to recycle the garbage that accumulates in their streets?

This is why social conscience is usually an aesthetic luxury for elites. They demand improvements to their cities so that the view through their mansion windows doesn’t clash with their everyday scenery. They fight against visual and sound pollution because it’s out of tune with their walks and bike rides. If they see a group of street vendors, they judge them as irresponsible people with no right to be on the street, never stopping to think about what brought them there. But the companies and factories that belong to these socially-conscious elites often indiscriminately exploit natural resources, even though they have recycling programs; they also benefit from the pitiful wages they pay their employees, even if they do give them–at best–social security and a meager pension that won’t be enough when it’s time to retire. The fight for a better world, as many academics and activists have argued, cannot be separated from a social restructuring process guaranteeing a much more egalitarian system. If it is, we’ll have cities within cities, walled-off spaces where all sorts of social and ecological utopias can be enjoyed, but whose functioning will continue to depend on the people who live outside, who pollute because they have no other option, who behave irresponsibly because they’ve never had the opportunity to do anything different; the people who are the workers, the employees, the assistants, the helpers and the consumers who keep the world running.

Three

The elite, who can enjoy silence, nature, and the chirping of birds, function in a way that is similar to many first world countries. As an example, we can look at the Scandinavian countries or their neighbors like Holland or Belgium. All of them, despite their bike-friendly infrastructure, their exemplary recycling programs, their renewable energy and their forward-thinking policies, have very large ecological footprints, right behind the greatest polluters like the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. How can this be? The answer is consumption: if this variable isn’t stopped, their ecological footprint–the amount of resources that the inhabitants of these nations use to live–will continue to grow. Regardless of the ecological policies these countries support, if they don’t think globally, if they build their prosperity on the backs of others–particularly on the backs of third world countries–their lofty ideals will not be achieved. These countries, just like elites who appear to have a social conscience, externalize the side effects of their success, and that’s why they believe they can change the world without even a millimetric change to the free market, the fierce competition that overexploits the poorest, or the financial deregulation that has turned the economy into a virtual casino. On the surface, their behavior is exemplary, and they might convince some that the path they are following will help to fight problems like climate change, for example. In contrast, when no one’s looking, they’ll continue extracting raw materials, deforesting lands, paying low wages, exploiting migrants, and flooding African countries with cast-off technology, passing it off as “second-hand merchandise.” Social consciousness should always be–especially during critical times like the coronavirus quarantine–about collective action, and not about individual acts that are done for one’s personal benefit and which, in the end, allow us to avoid talking about the true causes of inequality, exploitation, and global injustice.

Uno

Están en las redes sociales, preocupados por el medio ambiente y llamando a ejercer nuestras responsabilidades ciudadanas: no tirar basura, no contaminar, respetar el paso de los peatones, ser bondadosos con los animales. Se unen a las mejores causas, aquellas que, en el papel, nadie discute porque promueven un mundo mejor: energías renovables, reciclaje, transporte en bicicleta, slow food. Se comprometen con la causa de las mujeres y exigen una respuesta inmediata de las autoridades ante problemas como el ambulantaje, la violencia y la corrupción. ¿Los reconoce? Quizás tenga a varios entre sus contactos en las redes sociales. Quizás piense que me estoy dirigiendo a usted porque, a decir verdad, muchos usamos las redes para denunciar los males del mundo, a veces más como desahogo que esperando un resultado inmediato o provocar un movimiento social. Sin embargo, me refiero a denunciantes que pertenecen a un sector minoritario, un sector que puede permitirse un estilo de vida que, para el grueso de la población, es imposible aspirar. Este grupo de personas, en distintas partes del globo, tiene enormes ventajas desde su nacimiento y forma parte de una élite que, por más esfuerzos que haga, no podrá empatizar con la realidad de miles de millones –cifra que ya está aumentando por el impacto del coronavirus– porque, simplemente, vive en un universo diferente. Esta élite, comprendiendo sólo superficialmente la emergencia climática y social, se siente con la suficiente legitimidad para demandar reformas a un sistema que, directa o indirectamente, la sostiene y beneficia. Por supuesto, no estamos ante una élite suicida que busca abolir sus privilegios para marchar con los desheredados del planeta. Estamos, más bien, ante personas que sufren una especie de ignorancia o ceguera acerca del lugar que ocupan en la sociedad. Si se hiciera una encuesta o se pudiera entrevistar a los miembros de este sector de la población descubriríamos, con sorpresa, que se asumen como víctimas del mundo que les tocó vivir y, seguramente, nos describirían las innumerables calamidades que sufren provocadas por los gobiernos, entre otros actores que los afectan. Incapaces de asumir sus privilegios o contrastar su vida con la de la gente de a pie, aquella que se expone en el transporte público viajando largas distancias hasta sus trabajos o que apenas puede planear sus quincenas por los magros salarios que cobran, se sienten vulnerables y, sobre todo, ofendidos por el estado de las cosas. De esta forma, adoptan para sí mismos el discurso de los inconformes, de los rebeldes, de pensar “fuera de la caja”, cuando, en realidad, su modus vivendi inutiliza, por contradictorias, sus proclamas.

Dos

Hace unos días el periódico El País publicó un artículo de título kilométrico: “El fenómeno de mostrar cuarentenas privilegiadas en redes abre el debate de la brecha social en Internet”. El artículo, acompañado por fotografías y videos, describe la nueva moda entre artistas, empresarios y socialités: presumir los faraónicos interiores de sus mansiones mientras disfrutan la cuarentena obligada por el coronavirus. Algunos aprenden nuevas habilidades, como cocinar, o, simplemente, dedican sus días a la tranquila observación de los jardines inmensos que rodean sus hogares. Por supuesto, esto no ha pasado desapercibido para algunos internautas que han criticado que, mientras millones pierden sus empleos o se enferman gravemente por el modo en que se ganan la vida, los influencers y privilegiados del siglo XXI se pregunten en sus bitácoras virtuales si deben comer salmón a la parrilla o al horno.

Los privilegiados en cuarentena, sin poder presumir sus viajes al extranjero o su vida en el exterior, presumen algo más importante, algo que pueden disfrutar en sus casonas y que, para los damnificados de la desigualdad, son bienes escasos: tranquilidad, silencio y tiempo. Esos bienes intangibles, disponibles a libre demanda para los que están arriba de la pirámide, son quimeras extrañas para los repartidores de comida que trabajan para plataformas de internet que les niegan derechos laborales mientras transitan por calles llenas de autos, de contaminación y de peligros. El silencio y distraer el ocio mientras cae la tarde en un amplio jardín es un lujo desconocido para quien vive en un departamento o casa minúsculos, para quien tiene dos o más trabajos y apenas le alcanza el tiempo para distracciones que lo alejen de su realidad, aunque sea por un par de horas, como el futbol o una película en la televisión. Desde esos retiros de lujo, la élite –además de las previsibles quejas por las acciones tomadas contra el coronavirus– pide acabar con la desigualdad, reforestar los bosques, cuidar el agua, apoyar las energías renovables para no usar los combustibles fósiles que están incendiando el planeta. También insisten, a través de sus redes sociales, en mejorar la arquitectura de las ciudades, construir banquetas anchas, rehabilitar parques o promover un diseño urbano incluyente. ¿Quién estaría en contra de esas ideas? Nadie. Pero cuando esto viene de un sector de la población que ha acumulado su riqueza explotando, con muy pocos límites, recursos naturales y humanos, el asunto queda sólo en un gesto vacío, creíble sólo para los ingenuos. Una acción verdadera que, además, está en sus manos, sería asumir los costos de su estilo de vida, es decir, revisar el origen de su prosperidad más allá de sus casas llenas de celdas fotovoltaicas, sistemas de recolección pluvial, bicicletas para transportarse y reciclaje. De esa forma descubrirían que la disparidad y el consumo desbocado son el verdadero problema. Si no se solucionan las desigualdades, si no hay una distribución más justa de los recursos, los cambios que promueve la gente de arriba serán aprovechados por los mismos ciudadanos que han estado y estarán en la cúspide. La sustentabilidad y ecología serán, como ya se puede ver en innumerables ciudades, bienes de lujo, utopías para la gente cuya única posibilidad es luchar por su sobrevivencia.

Cambiar un sistema que ha depredado el medio ambiente y a generaciones enteras de seres humanos, debe ir más allá de la individualidad para buscar la organización colectiva. De otra forma, por más que se afirme o trate de demostrar lo contrario, la llamada “conciencia social” será, simplemente, una nueva etiqueta para “el buen vivir”. La lucha social y ecológica emprendidas desde el privilegio serán un placebo o, en el mejor de los casos, iniciativas que se concretarán en los pequeños guetos de lujo en los que vive la élite. Desde ahí seguirán pontificando, aleccionando a los necios que transitan en las calles contaminando o a los ciudadanos poco educados que no quieren cambiar sus costumbres dañinas. Por supuesto, hay una responsabilidad que involucra a las personas que viven en los márgenes de la prosperidad, pero los privilegiados les endilgan la misma capacidad de acción que tienen ellos porque, simplemente, no los conocen y, por lo tanto, no pueden imaginar cómo son sus días. ¿Tendrá oportunidad de usar la bicicleta y combatir la contaminación el empleado que sale del turno en la noche y que vive muy lejos de su trabajo? ¿Podrá acceder a la comida orgánica la familia que, a duras penas, puede costear la despensa conformada por alimentos producidos de forma masiva? ¿Podrán ser ecológicos y sustentables los que sufren por el suministro de agua potable? ¿Habrán tomado talleres de cómo reciclar si la basura se acumula en sus calles?

Por estas razones la conciencia social de la élite es, la mayor parte de las veces, un lujo estético. A través de sus demandas buscan mejorar las ciudades para que la vista, a través de las ventanas de sus grandes casas, encuadre mejor con la escenografía en la que se mueven diariamente. Luchan contra la contaminación visual y sonora porque desentona con sus caminatas o sus viajes en bicicleta. Si observan un grupo de vendedores ambulantes los calificarán como un grupo de gente irresponsable que ocupa sin permiso la vía pública sin pensar en las causas que los llevaron a las calles. Sin embargo, las empresas y fábricas de ellos, la élite con conciencia social, a menudo explotan indiscriminadamente los recursos naturales, aunque tengan programas de reciclaje; también se benefician de los salarios poco dignos que les pagan a sus empleados, aunque les den, en el mejor de los casos, seguridad social y una magra pensión que será insuficiente cuando llegue la hora del retiro. La lucha por un mundo mejor, como lo refieren muchos académicos y activistas, no puede desvincularse de una reorganización social que garantice un sistema mucho más igualitario. De otra forma, tendremos ciudades dentro de ciudades, lugares amurallados en los que se pueden realizar todas las utopías ecológicas y sociales, pero cuyo funcionamiento seguirá dependiendo de los de afuera, los que contaminan porque no tienen otra opción, los que se comportan irresponsablemente porque nunca tuvieron la oportunidad de hacer otra cosa y que son los obreros, empleados, asistentes, ayudantes o consumidores que mueven al mundo.

Tres

La élite que puede gozar del silencio, la naturaleza y del canto de los pájaros, se asemeja al funcionamiento de muchos países del primer mundo. Pensemos en el ejemplo de los países escandinavos o vecinos de ellos como Holanda o Bélgica. Todos, a pesar de su infraestructura ciclista, su reciclaje ejemplar, sus energías renovables y sus políticas de avanzada, tienen huellas ecológicas muy grandes, sólo debajo de los países más contaminantes como los Emiratos Árabes Unidos y Qatar. ¿Cómo puede suceder esto? La respuesta es el consumo: mientras no se detenga esta variable, su huella ecológica, es decir, la cantidad de recursos que usan los habitantes de esas naciones para vivir, seguirá en ascenso. Por más políticas ecológicas que promuevan estos países, si no piensan globalmente, si construyen su prosperidad a costa de los otros, particularmente de los países del tercer mundo, no se conseguirán los altos ideales que proclaman. Estos países, al igual que la élite con aparente conciencia social, externalizan los efectos secundarios de su éxito y, por eso, creen que pueden cambiar al mundo sin mover, ni un centímetro, el libre mercado, la competencia voraz que esquilma a los más pobres y la desregulación financiera que ha convertido a la economía en un casino virtual. Por afuera muestran una actitud ejemplar y, quizás, convencen a algunos de que la ruta que siguen ayudará, por ejemplo, a combatir problemas como el cambio climático. En contraste, fuera de los reflectores, seguirán extrayendo materias primas, deforestando bosques, pagando salarios bajos, aprovechándose de los migrantes, inundando de basura tecnológica a países africanos haciéndola pasar como “mercancía de segunda mano”. La conciencia social debe ser, en todo momento, y más aún en periodos críticos como la cuarentena obligada por el coronavirus, un acto colectivo y no acciones individuales, hechas para goce personal que, a la postre, evaden poner sobre la mesa de discusión las causas profundas de la desigualdad, la depredación y la injusticia global.

Alejandro Badillo, es escritor y crítico literario. Es autor de Ella sigue dormida, Tolvaneras, Vidas volátiles, La mujer de los macacos, La Herrumbre y las Huellas. Fue becario del Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. Ha sido reconocido con el Premio Nacional de Narrativa Mariano Azuela. Su Twitter es @alebadilloc

Alejandro Badillo, es escritor y crítico literario. Es autor de Ella sigue dormida, Tolvaneras, Vidas volátiles, La mujer de los macacos, La Herrumbre y las Huellas. Fue becario del Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. Ha sido reconocido con el Premio Nacional de Narrativa Mariano Azuela. Su Twitter es @alebadilloc

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

¡Ja! Tal cual hace Europa con el resto del mundo. Primero deshizo, industrializó, arrasó… hoy nos educa para darle una respiración a la Tierra y larga vida a la humanidad. Vienen con sus euros de un mes a comprar hectáreas que uno no compra con el trabajo de 10 años… pero vienen a hacerlo bien. Así se remarcó, pero a lo individual: universitarios hablando de una conciencia que lograron hasta tener el beneficio de estudiar en una gran institución a costa de miles que no irán a ella; hippies con doctorado que viven del estado desde los 20 (¡a sus 40!) súper conscientes, cero kitsh, muy anarcos, que se quejan de… ¿de todo?

¿El siglo XXI descubierto en la pandemia? No lo creo, pero qué bueno que se visibilicen sus lujos. El fascismo hoy es muy aceptado porque lo reparten los “buena onda” a diestra y siniestra y anteponiendo una máscara de pura rebeldía light, revolución pasiva y mucha conciencia. Hasta la burocracia usa lenguaje incluyente y no se uniforma… ¡qué va!

Hacen falta más textos al respecto, pero también mucha autocrítica. O cinismo, cuando menos, para hablar bien derecho.