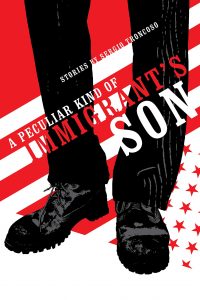

A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son Review

Greg Walklin

Not many authors—especially those still living—have a library named after them. But if you’re in El Paso, you’ll see, along Alameda Avenue, the Sergio Troncoso branch of the El Paso Public Library. Like many of the characters in A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son, Troncoso, the son of an immigrant, grew up in the Ysleta neighborhood of El Paso. He then went on to Harvard and later Yale, where he has long taught nonfiction writing at the Yale Writers’ Workshop. Troncoso has written five books, including collections of stories and collections of personal essays, often focusing on various types of borders.

The short stories in A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son, his latest book, are all linked: many share the same characters, and some—in a neat narrative trick—even cause one to entirely reevaluate a previous story. Generally, they move from stark, spare realism in the first few stories, to lush dystopian surrealism in the last few. Although many stories take place far from the Rio Grande, this is a robust, proud exploration of what it is like to be (on what one character calls) “the edge of the edge of the United States”: to be the child of immigrants, to be straddling two worlds—lines between love and sex, past and future, civilization and brutality, life and death.

If he desired, Troncoso could probably write a pretty good thriller novel, as evidenced by “New Englander,” where an academic encounters a thief in his home, and “Fragments of a Dream,” involving a confrontation when an obsessed, incestuous uncle encounters his niece in flagrante delicto with her boyfriend. Both are raw and unsettling, but in an affecting, visceral way, reminiscent of a less hardboiled Don Winslow. They could have been arresting climaxes to long novels. “Library Island,” one of the finest stories here, itself could probably be spun into a great novel.

“Library Island”—and the story it links with it, “Carmelita Torres”—explore in stark terms America’s attitude toward immigrants: “Why do we blame them for our failures, our diseases, our imaginary evils?” “Carmelita Torres” asks. “Is there a bottom to the abyss of our cruelty?” The ongoing crisis at the border between Mexico and the United States has revealed that if there is a current bottom, it is probably caging and separating children from their parents. Instead of setting a story in contemporary times, though, Troncoso focuses on a single moment in 1917. Arturo (who also appears in “Library Island”) magically communes with a woman trying to cross a bridge from Mexico to the United States more than a century ago. She is repeatedly beaten, raped, humiliated, and then held captive. “History is always a new beginning,” the story teaches, “yet also a repetition and a return.”

The animosity doesn’t stop with immigrants—it continues on to their children and to other groups who face discrimination. “Library Island” imagines a dystopian, homophobic United States in tatters because of—in the words of the single news agency, only extant after the “licenses” of its competitors have been revoked—“illegal invaders from outside the company territory.” A couple, Edward and Chris, inform their friend Arturo that they are planning to abscond to a place that “may not even be an island but somewhere in the rural west, a hidden fortress city, a sanctuary…” After tragedy strikes, Arturo tries to make his own way to Library Island, where he is captured and put to a test—he must endure days and days of intense reading comprehension testing from “interlocutors,” who quiz him on the boxes and boxes of books he is compelled to read. (This story reminded this reader of how Edward Gibbon called English grammar school “the cavern of fear and sorrow: the mobility of the captive of youths is chained to a book and a desk.”

The satiric point in “Library Island” is clear, but that makes it no less powerful—the rejection of books, of reading, of intense focus on the written word, denies us of something essential to our humanity, to what makes us think more deeply, empathize with those outside of our immediate families, and rise above our baser instincts. (Perhaps in recognition of this, the Troncoso Branch offers a prize to youth for reading during the autumn of each year.)

And that is precisely what these stories do: channel a particular type of experience with verve and pathos. Through stories contained and epic, restrained and overflowing, Troncoso also displays some considerable range; but he is at his best either going beyond straight realism, or in employing stream of consciousness. The stark police station tragedy “Yamecah,” the revanchist fantasy “Face to Face,” and the contained airplane conversation piece “Cross-Cutting Rivers in the Sky” aren’t bad stories, but lack the impact of the more imaginative tales. That is probably because they feel more like bridges, connecting other tales, rather than being robustly self-contained. Troncoso’s voice needs room to breathe—he possesses such a keen an eye for the roles of history, culture, and philosophy that a straightforward story without rich allusions and linguistic fireworks seems like a boxer holding out his knockout punch.

In “Eternal Return,” a story involving a magical hot chocolate that allows one to communicate with the past, Troncoso captures the feelings many of the characters throughout this volume are victim to: “He is behind in a race he knows nothing about—that is what he feels. He was born behind. But no, that certainly isn’t it. He is in a race where he doesn’t know the rules and doesn’t know how to avoid mistakes and dangers. Yet he has no choice but to race.”

Near the end of the book, Carmelita Torres defiantly exclaims “¡Yo soy de la frontera!” That proud statement could have been an alternative title “A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son.” Yet being de la frontera can lead to a constant shifting, Troncoso seems to be telling us—to ambivalence, faint-heartedness, indecisiveness. Multiple characters agonize and constantly reconsider their affairs, their spouses, and the directions of their lives, perhaps none in a more vivid way than through the mind of a lothario in the Iraq war story “Turnaround in the Dark.” What sets them apart is a dogged persistence in the face of hatred, indifference, and misunderstanding. As the narrator of “Rosary on the Border” succinctly notes: “I believe in very little, but I kept going until I would get tired or defeated, and then I would take time to discover another wall to throw myself at.”

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing

Posted: February 4, 2020 at 11:31 pm