Boyhood: Nostalgia for Ourselves

Hipatia Argüero Mendoza

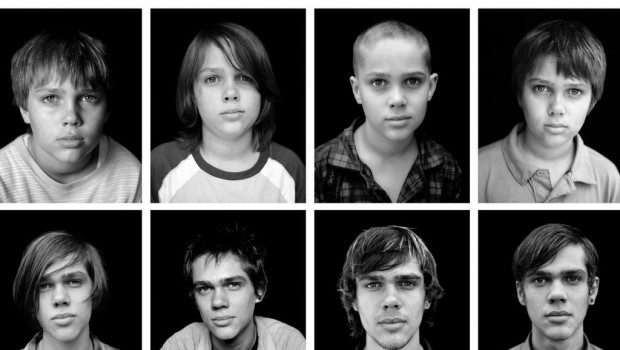

The first chords of Yellow, Coldplay’s hit single, start playing as we meet Mason (Ellar Coltrane)—whose entire childhood is about to be summarized before our eyes—lying on the grass. Such a familiar beginning is striking; singing along in my head, almost inevitable. How old was I the first time I heard it? I must have been about eleven. I remember walking on the beach, listening to it on my sister’s state-of-the-art MiniDisc player. What a relic it seems now. At the time I thought it was a very beachy song; now I know I used to think so predominantly because of the music video, which features lead singer Chris Martin walking along the shoreline in what must have been a bad trip. The song sets the year better than a super would: it’s 2000, Parachutes has just come out and the world has yet to see Britney Spears rise, the Twin Towers fall, wars begin and–sort of–end, Obama get elected and, of course, the grand finale of the Harry Potter series. Shot over the course of twelve years, Boyhood is Richard Linklater’s masterpiece.

Olivia (Patricia Arquette) is a single mother with two kids: the quiet Mason, still trying to figure out life (where do wasps come from?); and Samantha (Lorelei Linklater), who has things pretty much sorted out: get good grades, annoy brother as much as possible. Mom decides they are moving to Houston because she wants a degree and a better life. The kids refuse, as kids do, and they move anyway. And so the journey of both childhood and adulthood begins.

The father (Ethan Hawke) intervenes some throughout the years. Split from the very beginning, both parents almost never interact. This is not a movie about forgiveness, about a family getting back together, or a couple finding each other after many years (no meet-cutes and goodbyes, no Julie Delpy, no Paris). Quite the contrary, in Boyhood love and relationships are unsuccessful and tumultuous with perhaps one exception, designed to last (but who knows for how long). Olivia has to shake off the wrong man three times during the movie, and Mason Sr. goes through the motions like any bachelor whose relationships are not relevant enough to even mention to his children.

Mason and Samantha go to school, make new friends, lose them, forget them and move on. They go bowling, camping, and baseball watching with their father. They grow older and become awkward. They get a stepfather, brother and sister: people who are supposed to last, to become family. But even family can be replaced, outgrown or, however tragically, left behind.

Parallel to Mason’s childhood (and we know the movie is about him only because it is boy, not girl or neutralhood in the title), the film also portrays the expectations and struggles of his parents. Ordinary problems, such as financial instability, scholarly ambitions, the search for love and the constant letdowns of a world where being self-sufficient is not always sufficient, set a backdrop for the boy’s coming-of-age story.

As boyhood empathy begins to wane and teenage self-importance starts to take over, the film’s focus shifts more decidedly onto Mason. He deals with peer pressure, lies to his friends about having sex and tries to look cool through very poor hairstyle choices. He makes out with girls on backseats, smokes pot, flunks tests, talks back to teachers, finds a hobby and turns it into a life-changing passion, applies for colleges and leaves home. All this is starting to sound too normal, undramatic even. If this is a coming-of-age-film, all the clichéd plot points seem to have been left out. Why would we be interested in the normal lives of a middle-class family?

Of course, shooting a film over the course of twelve years is a great feat. However, an original approach and a lot of patience will never be enough to make up for a lack of storyline. Composed of short fragments, many unrelated and inconsequential (much like real childhood), Boyhood not only builds characters, but a lifetime. The effect is tear jerking, but why?

We notice time passing in the smallest things: music, length of hair, seasons. Near the beginning of the film, Mason digs up the corpse of a small bird and stares at it in bewilderment. It’s his first confrontation with mortality. The bird has been long dead when he finds it, and Mason knows the world has lost a living creature: the natural order of things. This innocent encounter with death reminded me of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem “Spring and Fall”, where the poet questions a small child’s reasons for crying over dead leaves:

Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leaves, like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! as the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you will weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sorrow’s springs are the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

It is the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

Margaret cries over dead leaves, but she is actually mourning over the realization of her own mortality. Everything dies. You will too and you know it, Manley Hopkins explains quite bluntly. For me, watching Boyhood is a lot like watching leaves for Margaret. It is not only Mason’s life that I’m watching, but my own, soundtrack and all. Dancing to The Hives’ “Hate to Say I Told You So” at a party I was too young for; being annoyed at someone singing along to “We’re All in this Together” during the High School Musical craze; being shocked at the realization that “Do You Realize” by The Flaming Lips is as cruel as it is sweet (are Mason and Samantha actually listening to the lyrics? Are they too young to understand?) Where was I when Mason was being driven home by his father, or when Olivia, Mason and Samantha got stranded after they finally left their abusive household? Relatability goes beyond the normal range, because we are watching real people grow and age. Real stories are being told, even if they are fictional. I’m transported to my own stubbornness in dyeing my hair red (thank god for vegetable dyes that wash out in a day or two), my own best friend giving me bangs using a blunt rusty blade. And when Olivia tearfully explains she has nothing else to look forward to (exaggerating like most moms would in a similar situation), I can’t help but think about my own mother and how lucky she was that we were late bloomers and didn’t leave home until college was well behind us (it’s normal in Mexico, honest).

Olivia, Mason, and their children just are. Life happens to them, as the hippie dancer says near the end: you don’t seize the moment; the moment seizes you. Boyhood is proof of the unscriptability of life, that we cannot truly predict anything (whoever knew Facebook would become a thing?), that paradigms can change in one day, and that we can only improvise our own reactions (although Boyhood’s dialogues are carefully crafted to look improvised).

In 165 minutes, twelve years have gone by and we’ve watched Ellar Coltrane become a full-grown boy and an awkward teen before turning into a beautiful young adult (was it just plain luck, or did genetics come into play during the casting process?). Twelve, real, tangible and memory-ridden years have come and gone. Not just for Mason and his family, but also for you. Maybe you also graduated high school, got divorced and remarried, played basketball, found love only to let it go, went off to college, bought a minivan after years of hanging onto a classic car and stopped dreaming about a career in music. Maybe you were also listening to Arcade Fire or Kings of Leon, or dancing to Crazy. Maybe your own story is being told through the lives of strangers. Maybe it is [insert your name here] you mourn for.

And suddenly it hits you: twelve years have truly passed and our lives are running out of cornerstones, as Olivia says in her final, heart-wrenching intervention. It is the blight that man was born for: the relentless passing of time. Leaves will die and fall. Kids will stop being kids. All that remains is to take comfort in the line uttered by two freshmen, high on mushrooms on their first day of college: it’s always right now.

Hipatia Argüero Mendoza (Mexico City, 1988) studied English Literature and Screenwriting. She is the editor of the film section of Cuadrivio Magazine. She likes cats. You can follow her at @MeLlamoHipatia.

Posted: February 5, 2015 at 7:00 am