Guillermo Kuitca. The “Death of Painting” Painting as a Resistance Movement

Mari Carmen Ramírez

Images courtesy of the Sperone Westwater Gallery

Guillermo Kuitca’s work has received significant international attention since 1985, when he represented Argentina in the XVIII São Paulo Biennal. He soon became one of the most influentially renowned artists to emerge from Latin America. The MFAH hosted a conversation between Mari Carmen Ramírez the Wortham Curator of Latin American Art and Director of the International Center for the Arts of the Americas and the artist.

* * *

Mari Carmen Ramírez: Every artist or movement that comes up with a new medium or a new approach to art claims they are responsible for the “death of painting” and that we need to move beyond it. Obviously, by researching digital media, video, and new technologies for applications in art, painting has become a more esoteric practice, but many young artists believe painting is an outdated medium about which there is little more to say. And yet, every so often, an artist like you comes along and, not only puts that argument to rest, but shows us new ways in which one can paint. So my first question is, what is painting to you?

Mari Carmen Ramírez: Every artist or movement that comes up with a new medium or a new approach to art claims they are responsible for the “death of painting” and that we need to move beyond it. Obviously, by researching digital media, video, and new technologies for applications in art, painting has become a more esoteric practice, but many young artists believe painting is an outdated medium about which there is little more to say. And yet, every so often, an artist like you comes along and, not only puts that argument to rest, but shows us new ways in which one can paint. So my first question is, what is painting to you?

Guillermo Kuitca: Many times the voice of an artist unfolds into a painting. I do not think that painting is a torch that has to be passed, nor is it a tradition that has to be maintained. Painting is a very resistant medium, but my intention is to make painting a resistant movement. The death of painting is happening to me too. I feel it while I am working, so I do not ignore it. There are moments in the practice when I can feel how all of those cycles come and go. What I believe makes painting so interesting and such a battleground is the mere fact that it has been declared dead; I cannot see another medium in which one can explore with such an incredible freedom. It is because the struggle occurs inside, it is very private. I think that the measure of the painting relies on what you can accomplish in that private moment. I am not so sure if you can achieve that in other mediums.

MCR: When you say that to paint is a private moment, is it a form of expression, like an urge that you need to bring out?

GK: I do not express myself through my work, and I do not think about why I am doing it, either. I like to think of painting in a more attractive way; it is like an indecent impulse. It does not mean that I am distant to the work, however. When facing it, the painting somehow becomes defiant, and then is no longer a reflection of my instincts. I am very aware of the role the observer takes in the process, too. What I mean is, though two people can look at one painting, they are both clueless as to what the other person is seeing. There are so many internal forces at play when looking at a masterful work that make it a poor medium for self-expression.

MCR: You started your career very early on; you were a child prodigy. There must have been something very important to you to paint at such an early age.

GK: I do not like to think of myself as a prodigy, I see myself as a precocious artist, though. Yes, I started very early, when I was nine and had my first show when I was 13. At that time I had a volume of work that I wanted to show. I did not know what to do with my work, and neither did my parents. So finally my father and I went to talk to some galleries and they found it very cute. We found a gallery that showed mostly established artists that was open to the idea, but they had concerns about the consequences of showing an artist at such a young age in terms of my future. However, I had a great sense of urgency, compelling me to show my paintings and keep working. Maybe because I was a shy kid, yet while I painted I did not feel shy anymore. It was at that time when I thought of painting as a way of expressing myself, but things change.

MCR: Where is the body of work from that very early period of time? Do you ever show that?

GK: Oh, no! Some are at my parents’ house, and some of that work has remained with me. The paintings I did before I turned 18 years old were very violent and depicted strict bodies, barbed wire and destroyed cities. I felt it was very superficial, and I hated it. I owned a studio while I was in school, so I would come to the studio every day and work with ink. I soon developed new work that tended to linger on serious themes. One of those first works was when the bed first appeared in 1982, and then it continued its presence in my work. You can find that bed appearing in all of the collection of that period.

GK: Oh, no! Some are at my parents’ house, and some of that work has remained with me. The paintings I did before I turned 18 years old were very violent and depicted strict bodies, barbed wire and destroyed cities. I felt it was very superficial, and I hated it. I owned a studio while I was in school, so I would come to the studio every day and work with ink. I soon developed new work that tended to linger on serious themes. One of those first works was when the bed first appeared in 1982, and then it continued its presence in my work. You can find that bed appearing in all of the collection of that period.

MCR: How did you come up with the theme of the bed? And what made you think that an everyday object could serve as a path to whatever you were trying to achieve at that time?

GK: I think the bed came to me as a sort of miracle. It spans the full range of human experiences: death, birth, dreams, sex… The amount of time we spend in bed notwithstanding, I found it to be a singular object that could embody so many ideas in such a simple way. You will see the subject of the bed come and go. I found that the bed is the closest object to the body one can paint without actually depicting the human figure. The projects that followed started with a simple bed.

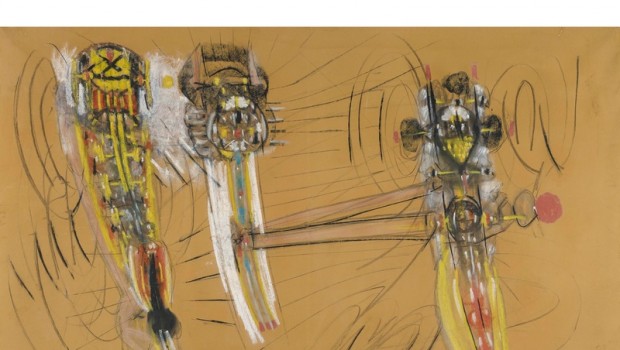

MCR: An image I find interesting is If I Were Winter Itself. It was conceived as one of your theater paintings during the period when you were very much involved with the choreographer Pina Bausch. You had a long relationship with that company and were involved in theater yourself. The more I look at these images, particularly as they evolve in my view, it is very clear that it is not so much about the theater itself, but about space. It is about the creation of a different kind of space. It was like you were searching to do something with it.

GK: Yes, I was doing some research on the theatrical… Curiously enough, at the time I did think of painting as a dead medium. In any case, I was very influenced and struck by Pina Bausch’s work. I found that that was exactly the type of work I wanted to explore. But if that was the style that interested me the most, why was I just painting? I treated my work as a theatrical piece. I began to believe that everything was possible in theater and nothing was possible in painting. That became my challenge. I also found that by painting small figures in big spaces, there was an activation of the space and it became a sort of trademark; it was the space defined by the scale. There were many notions surrounding the use of space that came about because of the size of the things. I started to feel that everything was about suspense, and all I was obsessively thinking about was space or options for space.

MCR: You have described the apartment plans, which became increasingly more abstract, as a part of the process of distancing yourself from your work; a period when you were feeling somewhat uncertain about what to do next while feeling a kind of anxiety and confusion. What did you mean by that process of distancing yourself?

GK: The distance started with the bed, then seeing the bed in a room, the room in an apartment, the apartment in a city, the city in the world and so on; it was like a zooming out. I was probably looking for a graphic language that allowed me to be freer in pictorial terms. The paintings of the house plans were as if they were painted on the floor. The depiction of the space became an architectural representation; the human figure was totally gone now. The result of this process of distancing was that I achieved a more objective view of the art in making a house. And this is probably a phase that gave away some of the thoughts I had. It is hard to see, but this depiction of the city, a living room, a house of some measured view and the bed was obviously a very sexual reference to coming; the white splash looks like a sort of ejaculation over the work, it imitates sperm. I was playing with the fact that coming was also coming and going, so there was a double meaning to the sexual idea. That movement of separation and coming was very much part of what I wanted to show. The house plan became sort of the icon to me. Somehow I treat this singular house plan, of which I did many variations, as sort of the iconography of the middle class/urban family type. A very important element that came to my work was the thorns. I found that I liked the idea of this apartment planning because it became a Christian-influenced element, not just working with rectangular figures. The thorns then took on a sort of life of itself. The first time they appeared it was in the depiction of a house plan.

MCR: The aspect of architecture then, as I see it, is depicted through these plans, and they in turn provide your work with a more rational view of its structure. But at the same time it introduced tension between the painterly approach and the rational approach. It is a tension that stays throughout your work, and begins here.

GK: Exactly, and that is a very good point. The use of architectural plans was really important because it allowed me some conceptual movement. Some of the other house plans had a more organic feel, as if they were bodies themselves. But in a way, all the house plans, with their arteries and veins, take an architectural language into an organic realm.

MCR: And did you have any interest in architecture before that? Was that a special passion of yours?

GK: It was a passion. I would not call myself a frustrated architect, but I am very interested in architecture. One of my mentors was a friend’s father, who was an architect and was the man who influenced me the most. That might be the reason why I see plans in a different way. They give you a sense that you are not in an abstract realm, but definitely not in the figurative realm. Because you cannot say that a map or a plan is an abstraction, but yet you cannot say it is a picture of a figure.

MCR: You may have been asked this before, but the whole notion of the plans…were you familiar with Ferrari’s demographic prints, circa 1980-82? He worked on those when he was in Sao Paolo, but they probably did not get much circulation.

GK: No they did not, but this is one of those things that are striking. Which in a way is sad, but so liberating. As an artist, sometimes you do not really notice who preceded you; although one should be able to do whatever one wants, regardless of who has done anything. There is an attitude that prohibits people from doing things. No one would say it in those words, but there is a widespread sense that if someone has done something, then you should immediately try not to repeat it.

MCR: How did you get involved with maps?

GK: I think it relates to the concept of zooming out I mentioned before. It sounds a bit too regimented, stating it in such a clear and rational way, but it did not happen that way. Every time I was looking for material, I would just happen to be intrigued by something and then I understood it at a later time. So it made sense that the next step after the house plans was all the maps. And I found that, again, I approached maps as if I was the first man on Earth that ever looked at a map. We did not have the Internet then, we were not in a digital world in 1991. It was the physical road maps, the physical city plans that I was desperately searching for.

MCR: How did you get them? Were they related to your travels? Or your personal experiences?

GK: No, of course not! I remember buying maps with no logical reason involved. It did not make any sense. I was attracted to the thought that I did not know a single thing about those places except names, figures and sounds.

MCR: Is the map providing you with a pictorial surface? Is it about the image? Is it about globalization or any of these other things that were happening at that time?

GK: No. One of the extraordinary things about living in the middle of something is that you just do not really realize where you are. I did not know that a map might have any relation to globalization, or the economy. In fact, I mostly thought of maps as a device to get lost and not to find your way. A map is a device that allows you to get your bearings, but to me they served as the opposite. On the other hand, I found really interesting to depict a kind of nightmare where no matter what road you decided to take, you always arrived in the same place you just left.

MCR: Some critics have related some of your work to the Holocaust, but you have rejected any kind of reference on your work.

GK: Exactly. The fact that I am Argentinean with a Jewish background does not mean that my work addresses the subject. So yes, I have tried to protect the abstract nature of my work.

MCR: Now after the paintings of the maps, you came up with different plans of spaces that were not so private. They were spaces that dealt with the public, like stadiums, prisons, hospitals and cemeteries.

GK: I was moving from very domestic units to the very institutional and larger realms. I tried to make a stronger statement about the importance of architecture in my work. It is curious that when the house plans became more public, the maps started to become more private. In a way they were two movements in opposite directions. I found that there was a collection of work called “people on fire”, which are like the regional charts I found. I just invented names and connected people, and I also used names I found in the telephone book.

MCR: How did the shift to theater seating plans come about?

GK: They might be the other side of the mirror. Let’s say that I look at the theater from the perspective of the actor; from the stage. I worked on a 180-degree turn looking at the stage and then looking from the stage. I like to think of the audience as a prompter, so the audience dictates what the actor says. I was then attracted to the idea that the drama was no longer on stage but in the audience. That is the reason why I made this rotation. It was interesting to see this shift in my work to the audience as a dramatic space.

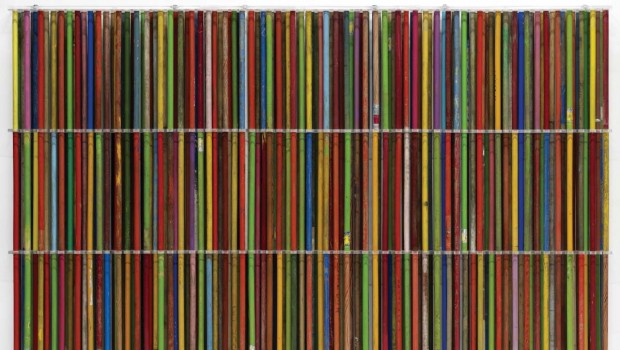

MCR: The color really bursts within this series. This intensity is not present in the rest of your work.

GK: You are right; it is hard for me to think in the terms of color. It might somehow reinforce the drama and it is all in the audience’s eyes. At some point I began to work with collages. I started out painting a lot and needed a break, and I found collages would provide an immediate response. They are just cut and paste. So I started to create these many city plans. Acoustic Maps was the name of this released work. I like to think that this is an acoustic reflection of what is happening onstage. In a way, it is the sound portrayed throughout the destruction of the theater; or maybe it is a burst of sound from the orchestra rather than the falling apart of the theater. This is an aspect of the work that becomes more liquid, more fluid, and a little more musical. I did some of this work by altering the coating on the photo paper. This saturation looks very dramatic, but I was very specific, and what I did very minimal. Sometimes I would just use steam or hot water or cold water, depending on what I wanted to achieve. The photo paper is good for photos, but once you do something that you are not supposed to do, it is a mess. It just takes the image somewhere else in a good way. Most of this work was created by editing what I wanted to keep, because most of the time the image came off of the paper completely. The times that I managed to keep something was because it became very interesting. I performed a kind of liquid effect. This was a larger work that I made using watercolor pencils. It activates with water it and moves the images from one place to another, and I found it fascinating.

MCR: What brought you back into painting then?

GK: I still wonder myself, because at that time I did not have a clue that this was going to happen. I was not paying attention to whether or not there were echoes to Picasso or García in modern tradition, nor did I refer to any particular paintings. I also do not like to think that it was related to style. I think it is connected to language; as I think of art as a historical language. I also make it my own and submit these articulations to the many elements of the repertoire. In a way, I tried to collide the modernist and post-modernist schools of thought. At the time it was seen as a sin, but maybe there were good reasons for that. I just thought of this as my language moving forward and not backwards.

MCR: There is no doubt that these paintings have a very different feel to them. It is almost like you are stimulated by this modern day language, your spaces, your maps, your entire repertoire… So the result is a very strange image. It draws you in, it is extremely fascinating, and it has an amazing surface. It defines modernist paintings, yet it is going in different direction.

GK: I hope so, and I feel that way. I think that is what is left of those maps, which were simply a few lines and some circles. If they had any chance to be referenced, it has been torn apart. The pictorial surface begins to feel a bit stranger. At this time, I really look for that quality. I like strange and ugly whereas in the past, they were things that I did not like. It also makes me think that using these vaguely historical references is not necessarily making quotations.

MCR: What I get from this is that you are actually enjoying the act of painting. It feels like joyous painting. It is almost like you’ve come full circle from the beginning.

GK: Yes, you are right. To have this happen to me now is like to have this wave submerge me. And I am not sure if I am drowning or surfing, but this is where I am now.

Posted: June 30, 2012 at 5:06 pm

Ronnie Daelemans and the other members of the Abe-x-ency team working on the Art-database-website of Artbooks-explorer, under construction, have downloaded this unexpected interes-ting site under ref.n° ART.II.2.011.2.D 010 Death in Paintings.They thank and greet sincerely the artist(s), author(s), editor, collaborators as well as all Art-lovers around the world.