Pim

Kenneth M. Ford

I was summoned to the Earth Intergalactic Council to investigate problems on planet, Z, site of the only human extra-terrestrial colony. (The Earth Intergalactic Council is rather ambitiously named.) Residents on Z specialized in neural prosthetics, in robotics, and in circuses. The circuses were an unexpected side effect of the slightly reduced gravity on Z and the fact that the first settlers were small but very strong, athletic people–two of which had worked in Cirque du Soleil.

The Z colonists had developed cyborgs, but now the cyborgs and the normal humans were at odds, and the Council feared that war might break out at any moment. My job was to understand their differences and reconcile them. So, I took the String Connector to Z, which transferred me almost instantaneously.

My arrival on Z found me in the midst of a crowd of normal humans. Immediately recognized by my official costume, I was taken to their Leader, who turned out to be four women and four men. I explained my mission and asked for the source of the conflict.

“The cyborgs have ruined our circuses. No one comes to see us any longer. Our acts depend on coordination. A group trick requires that everyone know where everyone else is and what they are doing. We have to plan and practice endlessly to get it right. If we don’t each do our job at just the right time someone will get hurt, the act will fail. The cyborgs, they can do almost anything spontaneously. Of course they have to practice to develop their agility and strength, but their cooperation seems completely spontaneous and violates the laws of physics.”

“For example?”

“Take the carnival trick: a guy turns his back on a woman with an apple on her head. The guy looks in a mirror, raises a pistol backwards over his shoulder and shoots the apple off her head. These cyborgs do tricks like that–but without a mirror. And they don’t have to practice. It’s as if someone else is aiming the gun. Or take a trick we do with a guy on top of a tower of people: he jumps off and they catch him. But we have to know which way he is going to jump. The cyborgs don’t have to know. The cyborg on top could throw dice to decide the direction and the cyborg acrobats would catch him every time.”

“So what else is wrong with the cyborgs?”

“They steal, and they cannot be caught. There is no way to sneak up on them. Each one always seems to know what the others are doing and seeing.”

“Even if you surround them, they cooperate in spontaneous, physical tricks. Like an ad-libbing Cirque du Soleil. Its humiliating.”

“There is no way to identify a leader or a commander. If we disable any number of them, the others carry on with this unfathomable cooperation as if nothing had happened.”

“So,” I asked, “how do you think they do it?”

“They are telepathic.” said one Leader.

“No, they can’t read our minds,” said another Leader, “they read each others’ minds.”

“They have a hive mind,” said another.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Well, I really don’t know,” said the leader, “but they all seem to know at the same time what the others are doing and seeing and hearing, all at once, and I never heard of multi-channel telepathy.”

“You are a society of robotic experts,” I said, “how could such a ‘hive’ mind possibly work?”

“It couldn’t,” three of the four said.

So I asked for safe conduct to the land of the cyborgs, who had taken up residence across a river. There, I met a woman of middle years who looked quite normal, except for a small patch on the side of her forehead–a large pimple in size, but more pleasingly aqua in color–the result, I inferred of the surgery that had made her a cyborg. She was with ten associates of different sexes and ages and she introduced herself as Pim.

Suddenly, one of the cyborgs climbed onto the shoulders of another, leaped into the air and dived head first toward the ground. I was sure she would shatter her skull, but at the last moment, two other cyborgs, both of whom had had their backs to her, spun, jumped and caught her.”

“What are they doing?” I asked.

“I am playing,” said my new cyborg acquaintance.

“YOU are playing?”

“Certainly” she said, “I am playing Dive of Death. I am also weeding the garden over there.” She pointed at a community garden in the distance where two or three cyborgs were hard at work. “We grow our own food rather than having the robots do it.”

“So you are all of these people at the same time?”

“You have the wrong concepts. In your terms, I am all of these people, and they are me, and they aren’t, and almost at the same time.”

“I am confused” I admitted. “Can you explain?”

“You are the first normal human ever to ask. The others here just shun us. It’s really quite simple. You must remember that sometimes you just do things automatically, without giving what you are doing any thought. You reach for your keys and put them in your pocket, you automatically say ‘Hello’ when you pass someone you recognize. You observe things going on around you without taking notice, although if you were asked you could probably describe much of what you observed. Actually, a good deal of your life is like that. But sometimes you have to plan and reason things out and make decisions.

“Sure, I have often done things I am not aware of until after I have done them. As if momentarily I was carrying out a computer program in my brain.”

“You were, a natural computer program. Each of my bodies is like that for a tiny fraction of a second, just executing instructions and gathering data from two eyes and two ears. Then, my higher cognitive function program arrives, gathers up the data, figures out what to do, gives a new set of instructions, and goes off to the next of my bodies. When it arrives in a new body, the higher cognitive function program has all of the data from the bodies it has recently visited, and uses that data to plan and decide what to do in the body it is now in. Then off it goes to the next.”

“How long does that take do a whole circuit, to record the data in one body, plan for that body, and move on to the next?”

“Not very long. I can make a circuit through ten bodies in a small fraction a second. A second is about what it takes a normal human to carry out any intentional act. And we’re getting faster with new technology.”

“So YOU are each of these bodies and each of them is you; your mind isn’t fixed in any one body, and no body is the leader or commander? How does that feel?”

“It feels great, like nothing you have experienced. Perhaps you have felt a little of it in a movie when the camera moved rapidly from angle to angle, shot to shot. But it’s different. Anyway, that is why we are so much better at circus acts than normal humans. And of course, we could be better at lots of things. ”

“Like what?” I asked.

After a moment, she continued: “Oh, just suppose we were warriors, or spies.”

I said goodbye and went to visit the normal humans. I advised them to start using elephants and tigers in their acts. It will be a long while before animals can be made into cyborgs, and who doesn’t like a circus with elephants and tigers? They thought it was good advice, and said they would take it. I went back, finally, to cyborg territory and spent some time with them before returning to Earth.

I met with the Council the day after my return. I was pleased to be able to report that the problems on planet Z had been settled amicably, and the Council was pleased with me. There was one question. A rather rude young Councilor had the gall to ask: “How did you get that aqua pimple on your forehead?”

* * *

PIM exists, its real, not for cyborgs but for robots. No robot houses the control program–it moves from robot to robot at the speed of light. Each robot carries out instructions left with it by the control program and records data until the control program returns, captures its data, and gives it new instructions. The process is very fast. Except by slim chance, destroying any one robot will not destroy the control unit, and the remaining robots will function intelligently and cooperatively. And if the control unit is destroyed, after a brief moment of assessing the situation, it would be regenerated from a previous copy. All that’s missing to have a human PIM is a connection to the human brain–but of course, that is a lot to miss.

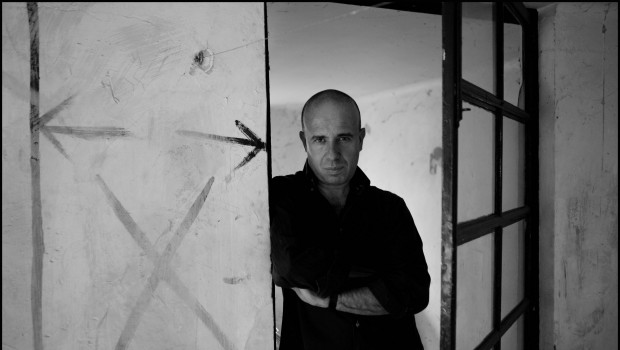

• Kenneth M. Ford is Founder and CEO of the Institute for Human & Machine Cognition (IHMC)–a not-for-profit research institute located in Pensacola, Florida. IHMC has grown into one of the nation’s premier research organizations with world-class scientists and engineers investigating a broad range of topics related to building technological systems aimed at amplifying and extending human cognitive and perceptual capacities. Dr. Ford is the author or coauthor of hundreds of scientific papers and six books.

* Image by Rose Mary Salum *

Posted: April 19, 2012 at 5:41 pm