The End of Women’s Silence

EL FIN DEL SILENCIO DE LAS MUJERES

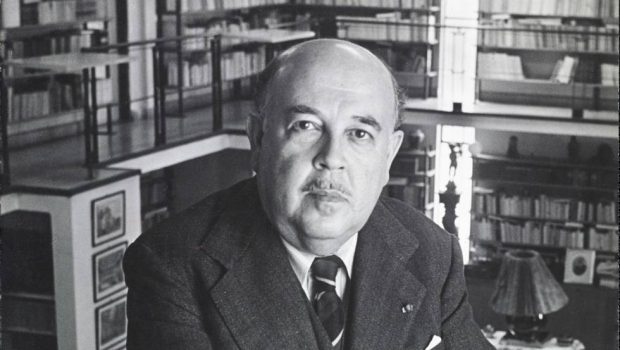

Cristina Rivera Garza

Translated from the Spanish by Sarah Booker

A Crónica from a Possible Future (1)

In the future, we will remember those final days of March as the days that shook our worlds. We were full of pain and rage, we will say. We were also full of hope. We were, in those days, a furious invocation for the truth. Our voices pierced the air and fell, round and firm, in other people’s ears. Our words, fervent, misbehaved, fatal wounds, survivors of everything, rose up before the eyes of the rest. It isn’t that everything had been calm before, but to the voices that had already risen, those of the women in the culture and art fields were added, taking a stance together. Everything in those days became ours because it was easy to say I am here, I know what this is about. Our stories, jumbled. Our voices, at the same time. It was so difficult to distinguish between what was your own and what was everyone’s, we will say with that great smile on our lips inspired by the community.

We had lived for decades under the frightening grind of femicide. Our mothers were dying, our sisters, our cousins, our neighbors were dying, even our enemies were dying. Everyone was dying; they didn’t stop dying. We got used to looking at each other with the grieving eyes of survivors: we wrote essays, we joined activism groups, we included more women on our class syllabi, we raised our voice in many marches. But there they were, they followed us everywhere, those statistics that kept increasing. Three women a day. Six women a day. Nine women a day. In January of 2019, ten women a day were murdered in Mexico. It was impossible not to wonder when it would happen to me. When it would happen to you, who looks at me, who is at my side. When will they kill us?

When the law of silence reigned, those killings seemed like somewhat anomalous eruptions in an inexplicably or irremediably violent world. The stories that were uncovered in the Mexican #MeToo brought to light and made evident the link between everyday violence and spectator crime. Every act of violence counts. There is only one step, and not a quantum leap, between domestic abuse, workplace inequality, daily harassment, sexual assault, economic mortification, cultural belittlement, lack of opportunities, and the murder of hundreds of thousands of women in Mexico and in the entire world.

Did we know these stories? Of course we did, sometimes by word of mouth, sometimes in our own flesh. As it became necessary, stories of #MiPrimerAcoso (#MyFirstAssault) and #RopaSucia (#DirtyClothes) were circulated. These were digital activism initiatives that collected women’s stories online. Were the rest aware? Of course they were, sometimes by word of mouth, sometimes in their own flesh. And, beyond the screens, there were the many support groups, the mothers of the disappeared, the Marea Verde (Green Tide), those that had said Ni Una Más (Not One More), to remind us of it. Thus, amplifying voices and extending the echoes of other shouts, all these stories dressed in sounds and letters, with proper and improper names in the public sphere, including twitter, took on a weight that in many ways felt like horror. We were also, we will say in the future, bowing our heads, even wishing that it hadn’t been real. It was a world founded on women’s silence. It was a world that required the most intimate silence from women, there where they are fatally wounded, to keep functioning.

And then it happened, we will say.

One woman began to speak, and another followed her, and another followed her, and another. They were very young, we will recount, but their stories were a lot like those that came from so long ago, as if everything had gotten worse over time. We knew it immediately: no one was going to stop the movement and no one was going to contain it. To exceed. To overflow. To get out of control. That is a social movement. Nobody participates in a revolt by raising their hand and waiting for their turn to speak. What comes to light is human and terrifying. We will say, recalling that poem by Ilya Kaminski that we had heard live in a salon or a warehouse full of people desiring its immediate translation, its proliferation, yes, we too lived happily during the war. And when they bombed other people’s houses, we / protested / but not enough, we opposed them but not / enough. I was / in my bed, around my bed Mexico / was falling: invisible house by invisible house by invisible house. / I took a chair outside and watched the sun. / In the sixth month / of a disastrous reign in the house of money / in the street of money in the city of money in the country of money, / our great country of money, we (forgive us) / lived happily during the war.

For years we didn’t want the war, but where ever we turned, there was the war, with its mass graves. With our disappeared. And with their money, yes. With that, too. But we no longer wanted to live happily during the war. We went together and marched, too, with everyone by our sides, in different groupings and packs, against that false happiness of the war. Some men recognized it and asked for forgiveness; others got scared. Others remained silent. And then, amongst the pain and the anxiety, amongst the fervor and the agitation, April dawned and Armando Vega Gil, the musician from Botellita de Jerez, the band with which many of us, at the end of the twentieth century, learned about irreverence and confidence, took his life after reading an accusation of assault on @MeTooMúsicamx, unleashing a backlash against the movement. We will have to say it with deep consternation, with a shared pain. In the future, we will take a pause, and we will remember his words: “It is correct that women raise their voice so that our rotten world will change.”

And then, just then, at the beginning of the cruelest month, the voice, the presence, the demand for justice became even more important. We will say that. We had all lost so much with the silence of women. And if some were beaten back into silence and others clung even more to the authoritarian and violent ways of the war, there were also those that demanded we continue, with hard facts, with radical empathy, with the ethic of care as a banner. There were tears in the interior of the movement and assemblies, we will recount. There was dissent. There was perplexity. And long hours of contemplation. And a lot of work, hours of dialogue and investigation, full workdays exchanging information and discussing strategies. There were open hands. And this frenzied, alive, plural energy, thanks to which we were able to keep living and to achieve this future—in which the laws that guarantee a world without violence against women are executed, the protocols for workplaces free of assault are respected, boys and girls have equal access to education, men and women receive equal pay, and in which six or nine or ten of us no longer die a day—that still depends on what we do today. It is not a more comfortable world, but it is one in which everything is discussed again, under the protection of all the eyes, all the bodies, because it affects all of us. That world, this possible future, requires all of our intelligence, knowledge, tenderness, disagreements, surprises. It requires it of you and of me. Now. Here. Because #NiUnaMás (#NotOneMore) for death, but #NiUnaMenos (#NotOneLess) for the fulfillment of remaining alive.

Cristina Rivera Garza is a Mexican author and professor best known for her fictional work, with various novels such as Nadie me verá llorar winning a number of Mexico’s highest literary awards as well as international recognitions. She is a regular contributor of Literal Magazine via her column Overcast.

Cristina Rivera Garza is a Mexican author and professor best known for her fictional work, with various novels such as Nadie me verá llorar winning a number of Mexico’s highest literary awards as well as international recognitions. She is a regular contributor of Literal Magazine via her column Overcast.

©LiteralPublishing

Una crónica desde un futuro posible (1)

En el futuro recordaremos esos días de finales de marzo como los días que sacudieron nuestros mundos. Estábamos llenas de dolor y de rabia, diremos. Estábamos, también, llenas de esperanza. Éramos, en esos días, una furibunda vocación por la verdad. Nuestras voces atravesaban el aire y caían, redondas y firmes, en oídos ajenos. Nuestras palabras, fervientes, mal comportadas, heridas de muerte, sobrevivientes a todo, se levantaban frente a los ojos de los demás. No es que todo hubiera estado en calma antes, pero a las voces que ya se levantaban entonces, se le sumaron las de las mujeres en las áreas de la cultura y el arte, pronunciándose juntas. Todo en esos días se volvía nuestro porque era fácil decir estoy aquí, sé de lo que se trata. Nuestras historias, revueltas. Nuestras voces, a la par. Era tan difícil distinguir entre lo propio y lo de todas, diremos con esa gran sonrisa en la boca que da la comunidad.

Habíamos vivido décadas ya bajo el espantoso molar del feminicidio. Nuestras madres morían, morían nuestras hermanas, nuestras primas, nuestras vecinas, incluso nuestras enemigas morían. Morían todas; no dejaban de morir. Nos acostumbramos a mirarnos con los ojos apesadumbrados de las supervivientes: escribimos ensayos, nos unimos a grupos de acción, incluimos a más mujeres en los programas de estudio en nuestros salones de clase, alzamos la voz en muchas marchas. Pero ahí estaban, a todos lados nos seguían, esas cifras siempre en aumento. Tres mujeres al día. Seis mujeres al día. Nueve mujeres al día. En enero de 2019, 10 mujeres fueron asesinadas al día México. Era imposible no preguntarse cuándo me tocará mí. Cuándo te tocará a ti, que me miras, que estás a mi lado. ¿Cuándo nos matarán?

Cuando imperaba lar regla del silencio, esas muertes parecían irrupciones más o menos anómalas en un mundo inexplicable o irremediablemente violento. Las historias que encontraron acogida en el #MeToo mexicano trajeron a colación y pusieron en evidencia al eslabón que va de la violencia cotidiana al crimen espectacular. Todas las violencias cuentan. Hay solo un paso, y no un salto cuántico, entre el maltrato doméstico, la desigualdad laboral, el hostigamiento cotidiano, el acoso sexual, la mortificación económica, el ninguneo cultural, la falta de oportunidades, y el asesinato de cientos de miles de mujeres en México y en el mundo entero.

¿Conocíamos esas historias? Claro que sí, a veces de oídas, a veces en carne propia. Por si hubiera hecho falta rondaban por ahí los relatos de #MiPrimerAcoso y #RopaSucia, iniciativas de activismo digital que recogieron historias de mujeres en las redes. ¿Estaban al tanto los demás? Claro que sí, a veces de oídas, a veces en carne propia. Y, más allá de las pantallas, estaban los tantos grupos de acompañamiento, las madres de las desaparecidas, la Marea Verde, las que habían dicho Ni Una Más, para recordárnoslo. De ese modo, amplificando voces y extendiendo ecos de otros gritos, todas esas historias vestidas de sonido y de letra, con nombres propios e impropios en la plaza de lo público, incluido twitter, cobraron un peso que en mucho se pareció al espanto. También eso éramos, diremos en el futuro inclinando la cabeza, deseando incluso entonces que no hubiera sido real. Se trataba de un mundo fraguado con base en el silencio de las mujeres. Era un mundo que requería del silencio más íntimo de las mujeres, ahí donde son heridas de muerte, para seguir funcionando.

Y entonces pasó, diremos.

Una mujer empezó a hablar, y le siguió otra, y a ésta le siguió otra, y otra más. Eran muy jóvenes, contaremos, pero sus historias se parecían a las que venían de tanto tiempo atrás, como si todo hubiera empeorado con el tiempo. Lo supimos de inmediato: a eso no lo detendría nadie ni nadie lo controlaría. Desbordar. Rebasar. Desbocarse. Eso es un movimiento social. Nadie participa en una revuelta alzando la mano y esperando su turno para hablar. Lo que sale a la luz es humano y aterrador. Diremos, recordando ese poema de Ilya Kaminski que habíamos escuchado en vivo en un salón o un almacén lleno de gente deseando su traducción inmediata, su proliferación, sí, nosotros también habíamos vivido felizmente durante la guerra. Y cuando bombardearon las casas de los otros, nosotros/ protestamos/ pero no lo suficiente, nos opusimos pero no/ lo suficiente. Yo estaba/ en mi cama, y alrededor de la cama México/ estaba cayendo: una casa invisible tras otra casa invisible tras otra casa invisible./ Moví una silla afuera y observé el sol./ En el sexto mes/ del insufrible reino de la casa del dinero/ en la calle del dinero en la ciudad del dinero en el país del dinero,/ en nuestro gran país del dinero, nosotros (perdónennos)/ vivimos felizmente durante la guerra.

Llevábamos años sin querer la guerra, pero a donde quiera que volteábamos allí estaba la guerra, con sus fosas comunes. Con nuestros desaparecidos. Y con su dinero, sí. Con eso también. Pero ya no queríamos vivir felizmente durante la guerra. Íbamos juntas, y marchando también cada quien por su lado, en distintas agrupaciones y manadas, en contra de esa falsa felicidad de la guerra. Algunos lo reconocieron, y pidieron perdón; otros se asustaron. Otros guardaron silencio. Y entonces, entre el dolor y la ansiedad, entre el fervor y la agitación, amaneció abril y Armando Vega Gil, el músico de Botellita de Jerez, la banda con las que muchos a finales del siglo XX aprendimos la irreverencia y el desparpajo, se quitó la vida después de leer un señalamiento por acoso en @MeTooMúsicamx. Habremos de decirlo con profunda consternación, con un dolor compartido. En el futuro, haremos una pausa, y recordaremos sus palabras: “Es correcto que las mujeres alcen la voz para hacer que nuestro mundo podrido cambie”.

Y entonces, justo entonces, a inicios del mes más cruel, se volvió todavía más importante la voz, la presencia, el reclamo de justicia. Eso diremos. Todos habíamos perdido tanto con el silencio de las mujeres. Y si algunas se fueron apaleadas de regreso al silencio, y otras se aferraron incluso más a los modos autoritarios y violentos de la guerra, estuvieron también las que nos conminaron a continuar, con datos duros, con empatía radical, con la ética del cuidado como bandera. Hubo lágrimas al interior del movimiento y asambleas, contaremos. Hubo disenso. Hubo perplejidad. Y largas horas de contemplación. Y mucho trabajo, horas de diálogo e investigación, jornadas enteras intercambiando datos o discutiendo estrategias. Hubo manos abiertas. Y esta energía desatada, viva, plural, gracias a la cual logramos seguir vivas y alcanzar este futuro—en el que las leyes que garantizan un mundo sin violencia para las mujeres se ejecutan, los protocolos de lugares de trabajo libres de acoso se respetan, niños y niñas tienen igual acceso a la educación, hombres y mujeres reciben igual retribución salarial, y en el que no morimos ya, seis o nueve o diez de nosotras al día—que ahora todavía depende de lo que hagamos hoy. No es un mundo más cómodo, pero sí uno en que todo es discutido de nueva cuenta, al amparo de todos los ojos, todos los cuerpos, porque a todos nos afecta. Ese mundo, este futuro posible, requiere de todas nuestras inteligencias, saberes, ternuras, desacuerdos, asombros. Requiere de ti y de mí. Ahora. Aquí. Porque #NiUnaMás para la muerte, pero #NiUnaMenos para la plenitud de seguir vivas.

Cristina Rivera Garza es la autora de Nadie me verá llorar (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 1999), La cresta de Ilión(México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 2002), La muerte me da (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 2007), Dolerse. Textos desde un país herido (Mexico: Sur+, 2011) entre otros. Su título más reciente es Había mucha neblina o humo o no sé qué (México: Literatura Random House, 2016). Es columnista en Literal Magazine. Su Twitter es @criveragarza

Cristina Rivera Garza es la autora de Nadie me verá llorar (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 1999), La cresta de Ilión(México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 2002), La muerte me da (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 2007), Dolerse. Textos desde un país herido (Mexico: Sur+, 2011) entre otros. Su título más reciente es Había mucha neblina o humo o no sé qué (México: Literatura Random House, 2016). Es columnista en Literal Magazine. Su Twitter es @criveragarza

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.