The Afterlife of Cotton: Los algodones

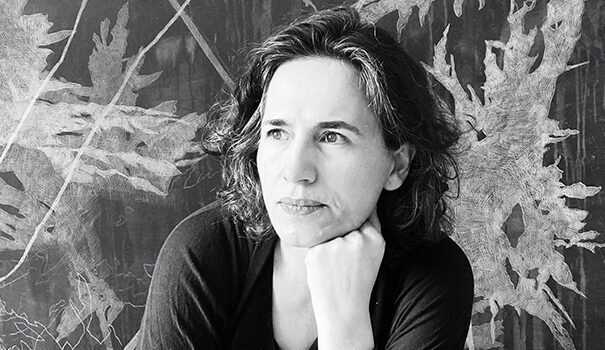

Cristina Rivera Garza

It was the summer Latinos became the majority in California; the same summer Donald Trump championed a flagrant anti-immigrant—and more specifically: anti-Mexican—agenda in trying to gain the presidential nomination of the Republican Party, attracting some thirty thousand supporters to one of his campaign meetings in Mobile, Alabama. Contrary to all things natural, we drove eastward, leaving an arid California, a very thirsty California, behind. No one ever said “go East, paradise is there,” but we tucked a few things in the trunk of the old Volvo 240DL, prepared towers of ham and avocado sandwiches, packed apples and water bottles, and off we went one early August morning. We expected nothing, which is another way of saying we expected a miracle. And why else would people travel?

Before airplanes hijacked all other forms of traveling, we used to drive old cars on two-lane highways, mesmerized by the speed and distance. The steady humming of the engine as a lullaby. Trains were the true kings for most the nineteenth century, powerful enough to change the parameters of time, and, even before that, wagons pulled by horses turned the earth into a hospitable surface. José Revueltas, a communist activist and aspiring writer, was nineteen years old when he rode on borrowed horses all day and all night long to get from Sabinas Hidalgo to Estación Camarón, a burgeoning town in the northern state of Nuevo León, very close to the border with the US. He was anxious and elated at the same time. His was not a literary journey, but an outing that would lead him into the very heart of a revolution that, he was convinced, awaited him in those dry, hostile lands barely covered by huizaches and cacti. A farm workers’ strike had just broken out in the cotton fields surrounding the Don Martín dam, the crown of Irrigation System No. 4, which former Mexican president Calles had inaugurated personally on October 6, 1930. Shortly afterwards, through the offices of agrarian reform, the government began distributing lands to would-be colonists in the zone between Estación Rodríguez, Estación Camarón and the recently created Anáhuac City. Fifteen hectares per family, a loan from the Banco de Crédito Ejidal, and the promise of more. In that early spring of 1934, Revueltas was trying to get to a social experiment run amok.

Cotton is cruel. Cotton is generous. King cotton. After a record harvest in 1932, the Mexican government actively sought to expand the cotton fields over vast tracts of norteño land. Striking deals with US investors and using the full clout of the nascent post-revolutionary state to break up long-held large estates, cotton soon dominated the horizon in Mexicali, Baja California; in Delicias, Chihuahua; and in Matamoros, Tamaulipas. Rumors spread fast. Landless peasants from the south and repatriated workers from the US arrived as if scheduled for appointments. Some of them were lucky and settled in, leaving their nomadic mores behind. Some had to try harder, and while waiting for an opportunity, hired themselves as farmhands. Following their lead, armies of cotton pickers arrived over the summer, raising tents and camping on site. The nocturnal vault pierced by the light of a thousand stars.

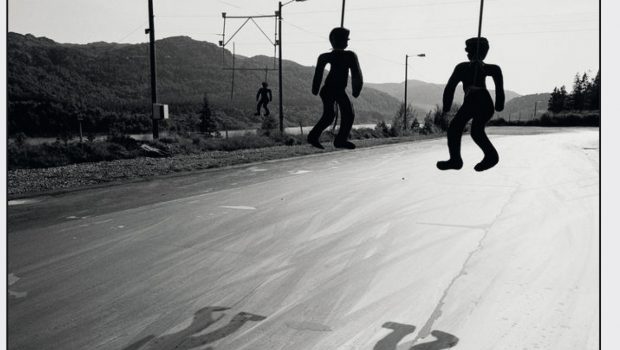

The cotton fields dreamed of cities and, soon, cities emerged out of the white. Designed by engineers to ease the flow of goods, these cities were circular ruins in the making. Concentric, ample streets enveloped round plazas and from their centers rose legendary obelisks indicating the four cardinal corners of the world and the three vectors of time: past, present, future. Especially the future.

That summer, the summer we went East, we were pursuing the remains of that future. As Borges had done in his own garden of circular ruins, we wanted to dream men and women as carefully as we could, in as much detail as humanly possible, just to be able to impose them back onto reality, turning that long-lost future into this present tense. A matter of conjugation. Something to do with life and death. And what is writing for, if not for this?

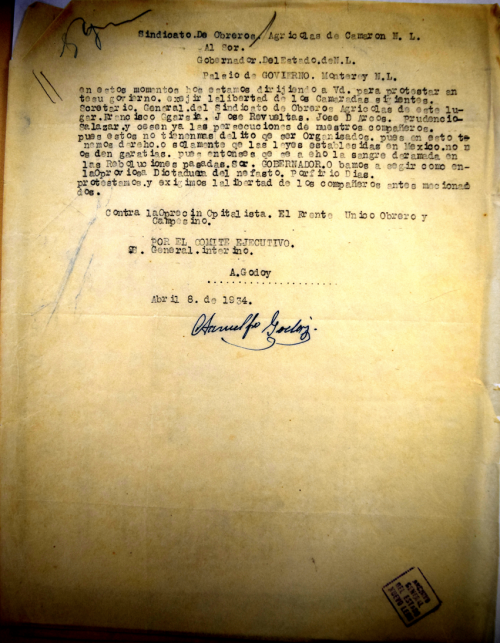

A very young José Revueltas helped us through the first stretch of the journey. He had briefly mentioned here and there that he had intervened in that relatively unknown farm workers’ strike, but up until then there was no evidence of such an experience. Urgent telegrams exchanged between local and federal authorities and, later, between unions and other leftist organizations and the government itself not only confirmed Revueltas’ version of these events, but also showed the lively nature of rural communism in northern Mexico, and its volatile, conflictive relationship with the State.

Revueltas explored much of his key experience at Estación Camarón in El luto humano, his second novel—a novel published in 1943 and translated into English not once, but twice. In 1947, still shrouded by the indigenista spirit that led much of the questioning around Mexican identity in the mid-twentieth century, translator H.R. Hays decided to title it The Stone Knife. It has been more recently, and more literally, translated as Human Mourning by Roberto Crespi.

The agrarian experiment has already failed by the time the novel begins: a small group of impoverished peasants witnesses the death of a child and death—the presence of death, the bitterness of death, the sweetness of death—impregnates their surroundings. Repeated flashbacks let the reader see and feel the cotton fields, especially the labor that transformed tracts of dry land into meadows of white gold. Revueltas did not miss the buzzing of tractors or the dignified demeanor of strikers as they quietly sang a melody while blocking the water entries. Using two or three adjectives in a row, or more if the situation called for it, Revueltas made patent the individual and social drama triggered by cotton as it established a paradoxical, yet utterly productive alliance with the post-revolutionary regime. For, let us not forget, cotton is both generous and cruel. King cotton is cruel.

This document proves that Revueltas was part of the Ferrara strike that took place in Estación Camaron, by March of 1934.

It is not common knowledge that a large portion of the agriculture practiced in northern Mexico has been closely tied to cotton production. Many of its cities are, in fact, the offspring of cotton. Both the drastic demographic increase and the remarkable economic growth of the norteño region in Mexico are historically related to the expansion of cotton fields. The emergence of a rural middle class, which sooner rather than later became an urban middle class, has strong linkages to cotton as well. As much as in the American South, cotton marked the economy, the landscape, and the culture of northern Mexico, albeit in a different way. While most of the land petitions were collective affairs involving participation in town meetings, where direct democracy was the norm, small private landholdings became paramount in the north, as opposed to ejidos—state property and collective usufruct of land—in the Mexican South. Resilience, resourcefulness and hard work, trademarks of the norteño character, all transpire in the ways in which farmers first approached the State, often instigating agrarian reform initiatives rather than responding to a state-generated program, as well as in the work practices and work ethic that permeated the cotton fields. The rapid mobility that resulted from this social and agricultural experiment only reinforced the sense of self-reliance and autonomy so dear to norteños even today.

However, the land, exhausted by monoculture, soon gave up. By the 1960s, soil erosion, excessive use of fertilizers, and a range of invincible plagues had brought the cotton experiment to a trepid end. Sorghum soon replaced cotton and then maquiladoras replaced sorghum in rapid succession. And then drug trafficking. And then pure violence. That summer, the summer we went East, we were following the traces of cotton, its very afterlife. Like a Hansel and Gretel of sorts, we picked up stories and sights as though they were tiny breadcrumbs distractedly or mistakenly left on dirt roads or the shoulders of highways. The clouds.

Los Algodones is a small town located on the northeastern tip of the municipality of Mexicali. Plural cotton: that’s what this name means, literally. Many cottons. Once a place designed to serve the needs of the cotton fields, Los Algodones now caters to US and Canadian seniors trying to secure cheap prescription medicine across the border. Lots of pills. Plural pharmacies. Dental offices with large neon signs. The afterlife of cotton is paved with cavities and broken bones, dreams of eternal youth and sexual prowess. Diabetics roam its streets. Cancer patients sip coffee. Other than the name of the town, cotton as such has but disappeared from both vision and memory. From Felicity to Winterhaven, the nomenclature of the desert suggests happy times, but the dunes near Yuma, imperial and white, and the recurrent, ominous presence of the border patrol hint otherwise. How many footprints have vanished here, swallowed by sand? Later along the trip, many Mexican immigrants would confide that they first crossed the border on foot, through the Sonoran desert. The run of their lives. We would look at them silently, in awe, remembering the weight of sunlight on naked skin those August afternoons. Reverberating, Revueltas used this sonic verb to indict the northern light all too often in his writings. The world on the other side of the windshield proved him right: to resound in a succession of echoes. Voices travel long distances: heat waves do too.

There is no cotton in sight in any of these places. I have yet to see my first cotton plant.

[1] José Revueltas, The Stone Knife, translated by R.H. Hays (New York: Reynal and Hitchcok, 1947); Human Mourning, translated by Roberto Crespi (University of Minnesota Press, 1990).

Cristina Rivera Garza is a Mexican author and professor best known for her fictional work, with various novels such as Nadie me verá llorar winning a number of Mexico’s highest literary awards as well as awards abroad. She is a regular contributor of Literal Magazine via her column Overcast.

Cristina Rivera Garza is a Mexican author and professor best known for her fictional work, with various novels such as Nadie me verá llorar winning a number of Mexico’s highest literary awards as well as awards abroad. She is a regular contributor of Literal Magazine via her column Overcast.

Posted: October 7, 2015 at 9:00 pm