The Heroic Ubiquity of Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott: talismanes

José de María Romero Barea

Translated by Keith Ellis

In adversity the sense of duty disappears. Failure to agree paralyzes governments, the opposing factions refuse to recognize the consequences of their demands. To solve problems implies rejecting the toxic spirit of irresponsibility. The emotion that permeates politics is not passion but disconsolateness. The press examines the loss implied in the collective uproar: incomplete sentences, not articulated, talismans that tarnish or illumine everyday reality.

All attempts to write about literature run the risk of falling into the detailed description of an empty space. Recourse to the essay may be said to offer the best investigative tool for a subject that necessarily eludes us. Involved in its own interests, an exegesis is always a transmission. It supersedes the challenge of creating complex characters who are emotionally damaged: what prevails is the strident eccentricity of the discourse. Our love of fantasy is borne out in its different forms of being, feeling and seeming: we set up defensive literary tactics against the cruel realities.

Violence underlies the decision to cling to lucidity in the dramatic work of the Nobel Prize winner in Literature for 1992, Derek Walcott (St. Lucia, 1930-2017), in whose work individual destiny gives way to the mythical dimension before disappearing. A voice digs deep and goes dark under the rugged tension. The lyrical voice of this Caribbean writer posits a subjective chronicle in which the wildest imaginative flights remain hidden under the immediate details. A consistent sensibility expands its scope before withdrawing to the imperturbable flexibility of what is to come.

We ask what has happened and we overlook the question of how are you feeling. We express our consternation about the disorder, alluding to our representatives to describe the collapse of values that we had thought to be eternal: empathy, solidarity, consensus. While the irrational takes charge of our experiences, the paragraphs become fragmented. We fight against preconceived ideas, we struggle to hide the anxieties that lie behind a confidence that is merely intellectual. But real events attack our expectations with their complex nature.

A model is chosen to whom homage is paid, but in an accessible way. Both for the Spanish Pre-Romantic and for the author now in our focus, Don Juan is a libertine who believes in divine justice (the line “there is no deadline that isn’t met or debt that isn’t paid” from the original, is transformed into “And may God help you … if you hate jokes!). In both, the seducer is confident that he can repent and be pardoned before he appears before God (the famous “What a long time you are giving me!” is changed to “that salt-sprayed eucalyptical Eden” where they could ‘’mix a few metaphors.”).

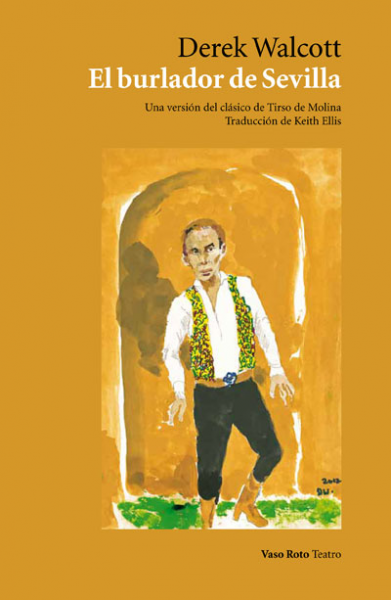

In El Burlador de Sevilla (Vaso Roto, Theatre, 2014), Walcott unfolds all his art in order to adapt, to his situation and that of his contemporaries, the Hispanic language and culture of the seventeenth century, while maintaining a radical originality and independence. Walcott’s sensitivity to the rhythm, the meter and the lyricism of the original, Tirso de Molina’s work of the same title (Madrid, 1584 – Almazán, 1648), makes of its adaptation a great achievement.

This version, nevertheless, suffers from the moralizing vocation of the original work. The joke and the seduction are converted into the perdition of a conqueror who happily cedes his soul and openly defies divine anger, on affirming: “one hour […] is all I have/ between your Hell and Ana’s Heaven,/ between her bed sheets and your grave.” The Caribbean seducer not only grazes the limits of the most cynical arrogance (“That is our misery: to love/ the very prison that we’re in./ And when love comes to free us, is/ redemption by the body sin?”) but he is proud of his religious scepticism (“My faith? The faith of all women./ The religion of women is love”).

The poetic drama is carried out through dialect, political commitment, translation and an ecological mentality. Walcott’s Don Juan falls in love: “Oh wound I envy, spring again/ like this fountain, drench me in blood!/ Lead me through a fine mist of rain/ toward love. Love is the good pain.” Salvation and entrance to the kingdom of the heavens are obtained through love (when not through sex): “I serve one principle! That of/ the generating earth, whose laws/ oblige the lion to move with long/ strides toward the idle lioness.” Don Juan does not trust in the salvation of his soul, since he doesn’t believe in everlasting life: “I am glad […] now that I am dying.”

The treatment of the public and private spheres and the form in which these concepts inform its reception, convert the counteracting of the lazy application of rhetoric to literature into a principal objective. An eternal defender of miscegenation, its author was born and grew up in Saint Lucia, one of the smallest islands in the Caribbean (population 160,000) where he received an English education. His generation, like his parents’, treated texts in other languages not like something alien or imposed, but like part of his mother tongue. As a response to that past colonial society, the action of The Joker takes place in a modern West Indian republic.

As a translatable allegory of darkness, for the dramatist this is a case of waiting for the nightmare of violence to end and for history to begin. The dichotomy white/black is discarded. Ethnic variety is stressed, thus the presence of indigenous, African and Spanish elements. The politics, then, fuses with the aesthetics and the discourse of the work, whose literary theory could be reduced to one single principle: make contemporary use of the devices of the tradition. In The Joker, imitation is not a form of adulation, but of creation.

On returning poetry to the theatre, both are enriched. A tool that promotes understanding, the tragic dimension takes up the myth of what it adapts, the most universal character in Spanish theatre. The legend of Don Juan is translated like something real. The intention is to center the public’s attention on the protagonist and his language. Criticizing consumerism and reification, the style of the seducer is elevated, even though the tone is familiar. Like Shakespeare before him, Walcott has his noble characters using a plain style.

Although the play is not set in Seville, expressions of Andalusian effrontery are used in it. Its society, just like the southern Spanish society of those times, is the incarnation of cruelty and merciless machismo. Like Tirso de Molina (and then Molière, Lorenzo da Ponte, Lord Byron, Espronceda, Pushkin, Zorrilla, Azorín, Marañon and many others), Walcott brings to our experience an old legend in order to condemn cases of sentimental identification with the inhuman world. While in poetry the voice speaks through an insurmountable divide, the pragmatic uselessness of theatre provides opportunity for stubbornness and self-deception.

When in 1974 the Royal Shakespeare Company commissioned from this writer, who would later be a Nobel Prize laureate in Literature, an adaptation of The Joker for the Trinidad Workshop Theatre, Walcott had already been working for many years in Port of Spain as a reporter for the Trinidad Guardian. At the same time he had been writing and directing for several theatre companies. The dominant tone is idiomatic. The rhetoric is never rigid. The Spanish version by

Keith Ellis (1935), poet, short story writer, translator, professor and researcher of Cuban, Latin American and Caribbean literature, of Jamaican origin, respects the dialect of the different characters. The standard language, from which springs the discourse, is converted to drama by masks, faces and characters. The style that Ellis employs is apt for transmitting intellectual subtleties. At the same time, he is faithful to the reflexive tone featured in the text, he knows the exact measure of the sound that he employs.

Another Life

Journalism helps us to purge the discontent that comes from inaction. It awaits us without vigilance while it keeps enigmas awake. It marks the inflection point where

the world and internal tumult meet. It favors the inaudible perforation of what captivates us. It prefers what is real to what is invented, it informs about the unknown in sentimental holes through which our legitimate curiosity is projected. By reading we see, we hear, we make commitments.

An irresistible naturalness coexists with a sensation of inherent difficulty. In spite of the sparseness of expression, the voice abounds in an eloquence that is not at all intrusive:

They melt from you, your sons,

Your arms grow full of rain.

“The Divided Child Chapter 2” (p. 132)

The poet demonstrates moderation, and nevertheless he comes apart in incidents and colloquial phrases that suggest impulsive intimacies:

One step beyond the city was the bush.

One step beyond the church door stood the devil.

“Chapter 4”

There is a heap of happenings. How does one assess them? There is bathos, but not verses that overwhelm us:

[…] if he saw autumn in a rusted leaf.

What else was he but a divided child?

“Chapter 2”

Walcott’s poetry is certainly not abstract: it involves a passionate criticism of contemporary life, the evaluation of a reality that is not suspect, but is implicit and almost irrelevant. How does one evaluate a collection of poetry that does not involve what is poetic? Let other factors be incurred in what is enigmatic or disobedient, self-satisfied or arrogant, but what is its value? What do we believe it to be worth?

A deep melancholy pervades Another Life (1973; Trans. Luis Ingelmo, Bilingual edition by Jordi Doce, Galaxia Gutenberg, 2017), a melancholy deepened by the fact that poets too know how to be ferocious, combative:

And then, one night, somewhere

a single outcry rocketed in air,

the thick tongue of a fallen, drunken lamp

licked at its alcohol ringing the floor,

and with the fierce rush of a furnace door

suddenly opened, history was here.

“Homage to Gregorias”

Between the impulse to be confrontational and to withdraw, the painter of Tiepolo’s Hound (2000) returns to places and persons: infancy, the countryside and existence in his native Saint Lucia, adulthood, friends and family.

The sudden modulations in the colloquial language recreate an accent that talks to our ear, a whisper that is made complicated by reminiscences created by context:

No metaphor, no metamorphosis,

as the charcoal-burner turns

into his door of smoke,

three lives dissolve in the imagination,

three loves, art, love, and death,

fade from a mirror clouding with this breath,

not one is real, they cannot live or die,

they all exist, they never have existed.

“A Simple Flame”

The final coda “The Estranging Sea” warns us against the inexact riddles that arise from evocations, the loose rhymes provided by memory, the assonances forgetfulness produces: “from that mist a man/ that they will not know how to recognize surges/ and staggers toward his own factions.”

On the second anniversary of his death, Walcott continues to be, against all predictions, free of pretensions. He organizes things in order to say naturally what others find it necessary to convert into enigmas. His work attracts us and, nevertheless it isn’t written in code, it doesn’t have that air of secrecy and superclassification that makes awkward the reading of others. Above all he doesn’t try to be auspicious or entertaining. The key to understanding that mixture of pride and humility can be found in this collection of poems that is darkened, like life, by what is lost, what hurts us downstream, what makes us question ourselves and doubt the idea of attachment. The bard of Omeros (1990) uses the formal structures of oral tradition in a lyrical work of essences.

Structural Raptures

Arranged quietly, in successive volumes, books do not aspire to be read. The best of them allude, if at all, to themselves. The fractured aspect reflects precarious mental states: prolonged flashbacks evoke periods of crisis. The requirement for overcoming them is to find new forms, more audacious and revolutionary metaphors, adventurous ideograms, experimental typography. Every author (or not) imagines a renewed language, of heroic ubiquity, that claims the right to the vigour of the devices in states of structured raptures.

In Walcott’s compositions the sentiment is captured with economical precision. The silence is seldom moving. His verses suggest matters that remain in suspense until they evoke parabolic meaning. In his theatrical production, the fairy tale enchantment is never concluded. Lullabies to keep us awake, his reflexions confront doubt and fear, they reflect on our vulnerabilities; faced with the negation of God, they cautiously announce his love, they take up again in annotations what remains to be said, they posit as footnotes fallen lives, echoes of the song of the earth, hunger for modernity, existence, such as it is, on the page.

The disaster is postponed when we speak with one voice about the future. Everything begins with dialogue. Our notions of what is public bore through what is personal to include descriptions of what is tender. The emotion of the discovery is represented in the concave mirrors of the press, in the convictions of the internal confusion combined with an astute eye for our times.

Sevilla, 2019

En la adversidad, el sentido del deber desaparece. La falta de acuerdo paraliza a los gobiernos, las facciones opuestas se niegan a reconocer las consecuencias de sus demandas. Resolver los problemas implica rechazar el espíritu tóxico de la irresponsabilidad. La emoción que permea la política no es la pasión sino el desconsuelo. La prensa examina la pérdida que supone el fragor colectivo: oraciones incompletas, no dichas, talismanes que ensucian o iluminan la actualidad.

Cualquier intento de escribir sobre literatura corre el riesgo de incurrir en la descripción detallada de un hueco. Un ensayo supone la mejor herramienta de investigación para un tema que necesariamente nos elude. Involucrada en sí misma, toda exégesis es transmisión. Supera el desafío de crear personajes complejos, emocionalmente dañados: lo que prevalece es la estridente excentricidad del discurso. Nuestro amor a la fantasía se cumple en sus diferentes formas de ser, estar y parecer: oponemos literarias tácticas defensivas contra las crueles realidades.

La violencia subyace a la decisión de aferrarse a la lucidez en la obra dramática del Premio Nobel de 1992 Derek Walcott (Santa Lucía, 1930-2017), donde el destino individual cede a lo mítico antes de desvanecerse. Una voz profundiza y se oscurece bajo la dura tensión. La lírica del caribeño supone una crónica subjetiva en la que los vuelos imaginativos más salvajes se mantienen ocultos bajo los detalles inmediatos. Una sensibilidad consistente se expande antes de retraerse a la flexibilidad imperturbable de la que proviene.

El burlador de Sevilla

Preguntamos qué ha sucedido y descuidamos el cómo te sientes. Expresamos nuestra consternación por el desorden, aludiendo a nuestros representantes para describir el colapso de valores que creíamos eternos: la empatía, la solidaridad, el consenso. A medida que la sinrazón se apropia de la experiencia, los párrafos se fragmentan. Luchamos contra las ideas preconcebidas, forcejeamos por ocultar las ansiedades tras de una confianza meramente intelectual. Pero la actualidad golpea nuestras expectativas con su naturaleza compleja.

Se toma un modelo y se lo homenajea, pero de forma accesible. Tanto para el prerromántico español como para el autor que nos ocupa, Don Juan es un libertino que cree en la justicia divina (el verso “no hay plazo que no se cumpla ni deuda que no se pague” del original, se transforma en “Y que Dios te ayude … ¡si odias las burlas!”). En ambos, el burlador confía en que podrá arrepentirse y ser perdonado antes de comparecer ante Dios (el famoso “¡Qué largo me lo fiais!” muta en un “Edén eucalíptico rociado de sal” donde mezclar “unas cuantas metáforas”).

En El burlador de Sevilla (Vaso Roto, Teatro, 2014), Walcott despliega todo su arte para adaptar a su situación y la de sus contemporáneos el lenguaje y la cultura hispánicas del siglo XVII, pero manteniendo una radical originalidad e independencia. La sensibilidad de Walcott para el ritmo, el metro, y el lirismo del original, la obra homónima de Tirso de Molina (Madrid, 1584-Almazán, 1648), hacen de su adaptación un logro.

La versión, sin embargo, adolece de la vocación moralizante de la obra original. La burla y la seducción se convierten en la perdición de un conquistador que entrega dichoso su alma y desafía abiertamente a la ira divina, al afirmar: “una hora es todo lo que yo tengo/ entre tu Infierno y el Cielo de Ana, / entre sus sábanas y tu sepultura”. El seductor caribeño no solo roza los límites de la más cínica arrogancia (“¿Y si lo que nuestro cuerpo necesita es un pecado?”), sino que hace gala de su escepticismo religioso (“¿Mi fe? La fe de todas las mujeres. / La religión de las mujeres es el amor”).

El drama poético se cumple a través del dialecto, el compromiso político, la traducción y la mentalidad ecológica. El Don Juan de Walcott se enamora: “Oh, herida que yo envidio, brota otra vez/ como esta fuente, empápame en sangre! / Condúceme por una llovizna fina/ hacia el amor. El amor es el dulce dolor”. La salvación y la entrada al reino de los cielos se obtiene a través del amor (cuando no del sexo): “¡Yo sirvo a un principio! El de/ la tierra generadora, cuyas leyes/ obligan al león a moverse con grandes/ zancadas hacia la desocupada leona”. Don Juan desconfía la salvación de su alma, ya que no cree en la vida eterna: “estoy alegre (…) ya que muero”.

El tratamiento de las esferas pública y privada y la forma en que estos conceptos informan su recepción, convierte el contrarrestar la aplicación perezosa de la retórica a la literatura en objetivo principal. Eterno defensor del mestizaje, su autor nace y crece en Santa Lucía, una de las islas más pequeñas del Caribe, donde recibe una educación inglesa. Su generación, tanto como la de sus padres, trata a los textos en otros idiomas no como algo ajeno o impuesto, sino como parte de su lengua materna. Respuesta a esa sociedad postcolonial, la acción de El burlador transcurre en una república moderna de las Antillas.

Alegoría traducible de la oscuridad, para el dramaturgo se trata de esperar a que termine la pesadilla de la violencia y dé comienzo la historia. Se descarta la dicotomía blanco / negro. Se hace hincapié en la variedad étnica, de ahí la presencia de elementos indígenas, africanos y españoles. La política, pues, se funde con la estética y el discurso de la obra, cuya teoría literaria podría reducirse en un solo principio: hacer el máximo uso contemporáneo de los recursos de la tradición. En El burlador, la imitación no es una forma de adulación, sino de creación.

Al devolver la poesía al teatro, se enriquece a ambos. Herramienta para la comprensión, la dimensión trágica aborda el mito de lo que adapta, el personaje más universal del teatro español. Se traduce la leyenda de Don Juan como algo real. La intención es centrar la atención del público sobre el protagonista y su idioma. Crítica del consumismo y la reificación, el estilo del seductor es elevado, aunque el tono es cercano. Como Shakespeare antes que él, Walcott hace que sus personajes nobles empleen un estilo llano.

Aunque el escenario no es Sevilla, se emplean expresiones de andaluza frescura. Su sociedad, al igual que la sureña de la época, es la encarnación de la crueldad y el machismo despiadado. Al igual que Tirso de Molina, (y luego Molière, Lorenzo da Ponte, Lord Byron, Espronceda, Pushkin, Zorrilla, Azorín, Marañón y muchos otros) se trata de acercar a nuestra experiencia una vieja leyenda para condenar las identificaciones sentimentales con el mundo no humano. Mientras que en el poema la voz habla a través de una división infranqueable, la inutilidad pragmática del teatro es oportunidad para la testarudez como para el autoengaño.

Cuando la Royal Shakespeare Company encargó en 1974 al que sería Premio Nobel de Literatura la adaptación de El burlador para el Taller de Teatro de Trinidad, este llevaba décadas trabajando en Puerto España, como reportero del Trinidad Guardian. Al mismo tiempo, escribía y dirigía para diversas compañías teatrales. El tono dominante es el idiomático. La retórica nunca es rígida. La versión al castellano de Keith Ellis (1935), poeta, narrador, traductor, profesor e investigador de la literatura cubana, latinoamericana y caribeña de origen jamaiquino, respeta el dialecto de los diferentes personajes. El lenguaje estándar, del cual surge el discurso, se convierte en drama a través de máscaras, rostros y personajes. El estilo que emplea Ellis sabe transmitir las sutilezas intelectuales. Al mismo tiempo, es fiel al tono reflexivo que el texto privilegia, conoce la medida exacta del sonido que emplea.

Arrebatos estructurados

Dispuestos calladamente, en sucesivos volúmenes, los libros no pretenden ser leídos. El mejor de ellos alude, si acaso, a sí mismo. El aspecto fracturado refleja precarios estados mentales: flashback prolongados evocan períodos de crisis. El requisito para superarlos es encontrar nuevas formas, metáforas más audaces y revolucionarias, ideogramas aventureros, tipografía experimental. Todo autor (o no) imagina un lenguaje renovado, de ubicuidad heroica, que reivindique la lozanía de los dispositivos en estados de arrebato estructurado.

En las composiciones de Walcott, el sentimiento se captura con económica precisión. El silencio apenas es conmovido. Sus versos sugieren asuntos pendientes hasta evocar una parábola. En su producción teatral, el encanto de cuento de hadas jamás concluye. Canciones de cuna para mantenernos despiertos, sus reflexiones se enfrentan a la duda y el temor, reflexionan sobre nuestras vulnerabilidades; frente a la negación de Dios, anuncian cautelosas su amor, reanudan en anotaciones lo que permanece, suponen notas a pie de página de vidas caídas, ecos del canto de la tierra, hambre de modernidad, la existencia tal como es, sobre la página.

El desastre remite cuando hablamos del futuro en común. En el diálogo todo comienza. Nuestras versiones de lo público horadan lo personal para incluir descripciones de lo tierno. La emoción del descubrimiento se representa en el espejo cóncavo de las rotativas, en las convicciones de la confusión interna combinada con el ojo astuto para nuestros tiempos.

Sevilla, 2019

José de María Romero Barea es profesor, poeta, periodista, narrador y traductor. Twitter: @JdMRomeroBarea

José de María Romero Barea es profesor, poeta, periodista, narrador y traductor. Twitter: @JdMRomeroBarea

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.