God is Round

Juan Villoro

Translated by Thomas Bunstead

The Football and the Head

1. DIFFERENT PASSIONS

I imagine that at the end of a chess tournament, Karpov and Kasparov probably start seeing things: people’s noses morphing into knights they might use to check their eyes. Football fever is no different. You might find in these pages the occasional hint of good sense, but bear in mind that once, when I had an actual fever, I came to the conclusion that if cough medicines were football players, the most fearsome midfield would be a powerful composite of Robitussin, Breacol, and Zorritone. In extremis, the football fan has a very ball between the ears. He rarely defends what he thinks, being too nervous thinking about what it is that’s being defended. When his team steps onto the pitch, the world, the ball, and the mind become one and the same thing. Utterly integrated into the scene, the fanatic turns to prayer or the stroking of rabbit feet.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the few people who don’t partake of football hate it. In spite of the obvious deficiencies of those who believe it makes a difference to roar “síquitibum!” (fans of the Mexico national team), “Visca el Barca” (Barcelona FC), “dale, dale Bo” (Boca Juniors) or “hala Madrid!” (Real Madrid), there are still some who react to the sport with mere indifference.

But that isn’t to say there aren’t plenty of people who enjoy adding to the bonfire of the footballs. Hatred can be enjoyable, a pleasure you cultivate, and perhaps football serves the secret function of annoying those people who honestly just want to be annoyed. Every so often a Nostradamus with no apocalypse on the agenda turns up at a match, wets a finger, and decides the wind is blowing ill. How is it that multitudes succumb to such a petty vice? The diagnosis grows increasingly dire when the World Cup interrupts the usual TV schedule, not to mention weddings: friends who beforehand seemed in good mental health begin peppering the conversation with the unpronounceable names of Croatian left backs. To rail against bad taste is, however, pointless: our friend Maria will forever prefer her mangoes green, just as Nicole Kidman will always go for beaus who are impossible to like.

The blights that accompany the kicking of footballs are many. A quick inventory of the things that cannot be magicked away by the team doctor’s medicine box: nationalism, violence in stadiums, commodification, and the objectionable sight of people with painted faces. All of this is obviously worthy of censure. But the pleasure we take in imagining things—there’s no fighting that. Every fan finds his or her own made-to-measure pleasure—or perversion—on a football pitch. In a world where some find Cathar poetry erotic and for others it’s edible underwear, it makes perfect sense that different people react differently. Ireland takes a poor performance by their national team as a wonderful reason to drink more Guinness, Mexico is sure to celebrate Mexico itself rather than relying on the team for a reason to party, Brazil soaks king-size flags in tears if the national team does anything but win, and Italy, if Del Piero misses a penalty, hurls the TV through the window.

The football trance makes us succumb to a frenzy almost entirely detached from reason. In a fan’s best moments, he or she recovers a portion of infancy, the primary kingdom where heroic feats, though subject to certain rules, ultimately depend on chance, and where, sometimes, come squally rain or blazing sun, when someone scores a goal it seems as though he has slain a leopard, and the torches of the tribe all come alight.

HOW DISGRACEFUL CAN WE BE?

In his or her lesser moments, the football fan is an ogling imbecile, mouth full of pie, head full of useless information. The Enlightenment obviously wasn’t meant to pave the way for cereal-packet hero worship, or to usher in a nirvana we blithely accept in which all sanity is suspended and backhanders are rife. It’s difficult to see where such fans fit inside the strictures of the post-industrial world. And yet there they are, and there they will always be.

There are some disintegrated societies in which Hamlet incites the murder of stepfathers and others in which football leads to acts of vandalism. In The Football War, Ryszard Kapuściński recounts the armed brawl that followed a match between Honduras and El Salvador; football can also serve as the catalyst for conflicts that have nothing at all to do with frustrations in front of goal.

As Elias Canetti showed, packed stadiums accentuate the potential of masses of people and can cause those possibilities to spill over. Not that this is always a negative: the uncontrollable crowd, when it sees what it’s become, sometimes completes the circle and discovers a voice of its own, as well as a critical conscience—as happened at the opening ceremony of the 1986 World Cup, in the Azteca Stadium. A year before, President Miguel de la Madrid had been unable to face the fallout from the earthquake in the capital city. He refused all foreign aid and contributed very little himself to alleviating the catastrophe. The people did far more than the government, turning out in the streets and putting the city back together themselves. And then those same people, gathered in the Azteca Stadium, faced down the elected leader, roundly booing him when he stepped onto the pitch. It’s no exaggeration to say that civil society was born in that very instant, one conscious of its own power, taking the first steps on the long march that would see the PRI voted out of office fourteen years later.

A DEATH IN BELGRADE: THE RAVEN’S LAMENT

Tyrants, sheiks, mafia bosses, plutocrats, drug lords, and other far-from-upstanding citizens—all have turned to football, waving the banner of certain clubs as a way of making up for their crimes and misdemeanors. Anyone wanting to find out about the dreadful deeds that football can give rise to need only spend a season with the Ultra Bad Boys, a group of Red Star Belgrade supporters. Franklin Foer did precisely this, and his book How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization provides transcriptions of the intellectual exchanges between the Red Start fanatics: “Who do you hate the most?” the interviewer asked one appropriately heavily tattooed individual. “Croats, cops, don’t mind. I’d kill either.” It’s chilling to think someone “doesn’t mind” in this regard, though such indifference doesn’t extend to murder methods, the Ultra Bad Boys’ weapon of choice being the metal bar.

What’s so lamentable about Red Star, what makes it seem like a bad joke, is that though it’s the police’s favorite team a large number of its fans are involved in organized crime.

I traveled to Yugoslavia at the beginning of the 1980s and heard the same thing time and again, the same refrain about Tito being the country’s rightful representative: “All the rest, they’re just Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Montenegrins…” But long before Marshal Tito’s integrationist dreams exploded into a war, Serbo-Croat tensions were detonating in fights between fans of Red Star and Dinamo Zagreb.

A character emerged from the tatters of the post-Cold War country, one straight out of a John Le Carré novel: Željko Ražnatović. A secret-police hit man during the socialist era, he moved up a rung to gangster as capitalism dawned in the country. After bumping off several Muslims, his gusto for taking people’s lives led him to start calling himself by the alias of “Arkan.”

The son of an air-force pilot, Ražnatović dropped out of navy school and fled to Paris, where he became a small-time criminal. In Foer’s summary of his incendiary CV: “In 1974, the Belgians locked him up for armed robbery. Three years later, he broke free from prison and fled to Holland. When the Dutch police caught him, he somehow managed to slither away from prison again… Back in Belgrade, he reconciled with his father and then worked his connections to the Yugoslav security apparatus.” Like so many criminals, Arkan was a puritan, only evil. On a trip to Milan, we learn, a friend invited him to an orgy, but he passed, opting to stay in his room and do his keep-fit exercises instead.

A Red Star fanatic, he took on one of the strangest jobs in the world of football. The Serbian Communist Party secretary at the time, Slobodan Milošević, asked him to infiltrate the Ultras and start organizing them to suit the party’s ends. Arkan brought discipline to the Red Star fanatics, and all the different factions ended up falling in behind him. His own Spartan conduct began to pervade the stands, and the stadium seemed to have been brought to heel. The only unchoreographed thing that happened there was the ravens flying up as a goal was celebrated.

But Milošević and Arkan had their minds on bigger prizes. Out of the Red Star Ultras an informal army was born: Arkan’s Tigers. They even saw action, in the Serbian offensive of 1991–1992. The violence, once spontaneous in the stands, became a matter of military tactics in a war—though perhaps “pillaging” is a better word for the actions of these cruel torturers. At the end of the genocide the scoreboard read: two thousand dead, and a fortune amassed in the looting.

Symbolically enough, Arkan moved into a house opposite Red Grade’s stadium. The locals viewed him as a pop idol, the hard guy who turned the hooligans into something “useful” at the same time as defending Serbia’s honor.

Arkan wanted to use his war booty to buy the club he so loved, and when that wasn’t possible he made do with another Belgrade side, FK Obilić. At least in name it seemed made to measure, Miloś Obilić being a warrior who, the night before the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, slipped through enemy lines and assassinated Sultan Murad. The fortunes of Arkan’s side quickly improved, due partly to referees worrying what would happen if they penalized a side backed by a group of paramilitaries.

The kinds of excesses you usually associate with managers and executives pale in comparison to Arkan’s abuses of power. Though this particular gangster’s arc ended in the usual way when he was shot down in the vestibule of a hotel.

Arkan’s strange legend folded in nationalist hopes, alternative centers of power, discipline in the eye of chaos, and sporting supremacy, and to this day the man still has his adherents in Belgrade, especially among the ever-expanding Ultra Bad Boys, whose numbers show no signs of abating. And his shift from criminality to the kind of illegal activities that went unpunished was all part of the country’s convulsive recent past, a truly bloody episode but of the kind that became the norm for many Serbians, an anomaly not dissimilar to the presence of the ravens in Red Star’s stadium.

ONE FOR ALL: FRANCESCO TOTTI

Let’s halt this impure train of words for a moment to consider a unique case of love for a club. In the ever-shifting world of transfers and agents, there has been one gladiator who refused to change course, however tempting the song of the sirens. He has plied in trade in Serie A, which is usually more than enough for great players, but for Roma, a side that spent long years in the wilderness before winning a scudetto, after the title machine Fabio Capello took over (leaving not long after, griping as usual).

The legend of Francesco Totti, immune to big money offers and the seduction of other shirts, has been a rare one in these globalized times. He was born in the Eternal City, but in one of its less hallowed spots. The writer Fernando Acitelli took it upon himself to count the steps between the Totti household and the imperial wall, and it turned out to be 264, just a few more than the length of a football pitch. The man beyond the wall went on to become the city’s symbolic heart. Maybe it had to happen in Rome—there’s almost too much symbolism there for it to have been otherwise. The fans have a flag—Caput Mundi—all roads lead to Rome, center of the world.

Totti is the only footballing superstar who has felt emotionally incapable of playing for another side. At the height of his fame, there were all kinds of sponsors clamoring to bathe in the reflected glory of his monomania. Quo vadis? The question simply didn’t apply. And yet there was a moment when Totti was more future than present and, like any legionnaire, felt the conflicting pull. But he resisted. He would go on to be an arrogant and at times dirty player, but, as the narcissistic Roman tradition dictates, and with a sentimentalism some find distasteful, when he lost control he’d always look to make amends—and above all, he never left. Francesco Totti, a.k.a. the addiction to belonging. If the Tiber doesn’t cross seven hills, the city’s worth nothing.

The Roman forward went through the single sentimental excess that Maradona could not: sedentariness. Totti is the ultimate stay-at-homer. Other calcio divas have had faces perfect enough to stamp on coins, but only he has done enough to merit the insignia of the truly untransferable.

In the strangely ascetic world of Italian football, where pleasure, like the tiny dark drops in a café ristretto, is at a premium, forwards are solitary creatures, hard-running and lonely. There he is, Francesco Totti, chasing lost causes, showing that one person at least is the city. Roma may be defeated, but still he stays on.

ABSOLUTE LOONS

Football is loved by too many people not to be enjoyed in a thousand different ways. It’s the most effective means ever invented for selling merchandise. No small thing when you compare it to other businesses. When all else fails, and the world seems to be on a constant downward spiral, TV will always come up trumps.

Money is what makes clubs go round, and in large measure it’s also what decides results. Real Madrid spent seven hundred million euros in the same period of time that tiny Osasuna spent ten million euros. It seems inconceivable that they should both be in the same league. But then again Osasuna have a very good record against Real, especially when they were under the stewardship of Javier Aguirre, and there’s also the fact that professional football has always been a stranger to economic justice.

Let us accept the inevitable: football represents other aspects of society in very complex ways, and it also allows for enormous stupidities. The beautiful game does awaken mankind’s propensity to shout and scream, but the best argument against this criticism isn’t rational, and it isn’t through ideas about the purity of the game.

In its democratic approach to passion, football incorporates the widest range of defects. When all goes well, it means, inoffensively enough, that people act badly in the stands rather than at home. How many living-room heart attacks have been averted by people diverting their vociferous behavior to the stadium?

Football’s like fiber in your diet: you don’t want it to be all you have, but a certain amount is good for clearing you out. People bring a lot to football, and so a lot gets eliminated there. We can hardly judge it by the sublime protocols one associates with opera, given that its very reason is to vent emotional excesses, to let the lunatic inside each of us take control for ninety minutes so that the person who comes home from the match might is, if no great humanist, at least reasonably normal.

Is there any way to classify the brief mental downgrade we undergo during a match? To be truly legitimate, a fan’s defects shouldn’t cause offense. So we come to the nub: if trying to resist football is pointless, proselytizing is also unlikely to get others on our side. No one can be convinced to “theoretically” delight in a goal. To talk about an enthusiasm that is so widely shared, as well as so vulgar, we need some other entry points.

Truly great moves have nothing to do with athletic capabilities, but a secret skill, in great part down to a psychological fine-tuning: Zidane filters a ball through a space containing exactly nothing, but into which Raúl is about to rush; Romario feints one way, left, and all eyes in the stadium follow; Valderrama stops, drops his arms to his side and goes to sleep standing up, like a siesta that is in fact the most surprising form of attack, the calm before the goal; Ronaldinho does all the above and still has time to thread it through to Eto’o.

There have been players—and Menotti is the best example—who didn’t achieve fairytale feats but could run their mouths like nobody’s business on the pitch. “So should I start running now?” El Flaco would ask an opponent, who then took his eye off the ball, not knowing that football was a tutorial on grass.

In trying to understand astonishing feats, the sports reporter ought to renounce all reason. Can anyone boast their way into a superior comprehension of the game? Of course not. The braggart won’t even really convince himself. Every witness plays against his or her own shadow, in the style of Gesualdo Bufalino: “Every day I take penalties against myself. Fortunately, or unfortunately, I always hit the post.” Football is wholly subjective: the spectator challenges his or her self and in trying to analyze everything in sight, once and for all and for everyone else, is bound to hit the post. In the never-ending activity of confusing the football and the head, there’s no way out.

THE SENSE OF TRAGEDY

To exist, the singular maestro requires a certain drama to surround him. Though footballers’ biographies are never as heartbreaking as those of ice skaters or Russian ballerinas, there needs to have been a certain amount of suffering in the past to generate the desire to shoot on goal. In 1998, during the World Cup in France, I attended one of Brazil’s training sessions. There are few things as tedious as watching the herd or regiment trotting around, and truly talented players also find it tedious and look for ways out.

That afternoon, Giovanni and Rivaldo broke off during a pause and played a game of hit the crossbar. Giovanni managed it five times in a row, Rivaldo three. Never in my life have I witnessed a useless feat of such exactitude. No person is born with such guidance systems inbuilt. You need to either come from a broken or disadvantaged home, or just a very strange one, to achieve such levels of obsessive virtuosity. Giovanni and Rivaldo hoped to get something out of their diligent target practice that is impossible to explain.

Like trekking or ballet, football allows for the sublimation of suffering into physical discomfort. Those less skilled at converting trauma into touches on the ball end up playing in defense, and those whose problems outweigh their talent specialize in the football version of “acting out,” by breaking up the game, or other players’ ankles.

We know very well from Tolstoy that happy families don’t generate novels. Nor do they produce footballers. You need to be very thirsty for consolation to want to put yourself on display in front of a hundred thousand baying fans and millions of prying media eyes. Opera singing, record breaking—it all points to something nasty in a person’s history.

In team sports, the sense of tragedy needs to be shared by the collective. If we think about Holland, their football story lacks drama. Rembrandt’s native country has enough chiaroscuro to fuel fights in bars, or even to make Harry Mulisch’s novels interesting, but its players lack the necessary dose of agony to win matches. It’s all the fault of the legendary Clockwork Orange: in the 1974 World Cup, Holland was such a goal machine that they could have put a gardener in goal and still won. Their captain Johan Cruyff wore the number 14—unheard of in those days, even slightly irreverent—and defied all the norms by popping up all over the pitch. It was at the World Cup in Argentina that they perfected their system of “total football,” with players constantly swapping positions and rotating around the pitch, and it actually bordered on sadism with the inclusion of two identical twins, the van der Kerkhofs: their opponents were forever confusing René and Willy. In 1974 and 1978 Holland was ahead of its time and dominated everyone but lost in both finals against less brilliant teams who nonetheless knew how to channel their inner pain to win trophies.

The ’74 Holland side lost to Germany, a side of veterans who took more pride in their scars than in their skills (some of these warhorses had taken part in epic losses, including the 1966 Wembley final defeat and the semifinal in Mexico in 1970). The only person to criticize the Clockwork Orange’s bullying approach with any eloquence was Anthony Burgess, who always saw football as little more than a vulgarity and at the time was concerned that his novel would come to be associated not only with a film he didn’t much like, but with a group of eleven sweaty Dutchmen. All the other commentators saw Holland as heralding a Renaissance on the pitch, and yet they lost to the long-suffering Germans, as four years later they would lose against the long-suffering Argentinians (Menotti’s side lacked stars and, strictly speaking, played against itself, in that they needed to shake off the support of their own military government as well as the disdain in which Argentinian players traditionally held the national side).

Perhaps these great Holland sides were never crowned World Champions precisely because they had it all to lose, and a secret compensatory law exists whereby the champions must show up already in some way battered and bruised.

WHEN IT COMES DOWN TO IT, GERMANY WINS

The 1954 World Cup in Switzerland was meant to be the confirmation of the supremacy of the Hungary team of the day. Though in 1950 Brazil had lost on their home turf, and against all odds no World Cup had ever had such clear favorites. Going into it, Hungary hadn’t lost a match in four and a half years.

Their route to the World Cup had included wins over England, a 6-2 at Wembley and a 7-1 in Budapest. It went down in the memories of fans who would never see the Danube but learned on those days what Kocsis, Hidegkuti, and Bozsik had in their boots. The sun they orbited around was Ferenc Puskas, who was more than capable of scoring with that left foot of his from a hundred feet out. The ’54 Hungary side can be considered the first to put 4-2-4 into practice and the first to really make full use of their central midfielders—that is, to understand that goals can be generated in the middle of the park, too. The goalkeeper Gyula Grosics was way ahead of his time, spraying pinpoint passes around from his penalty box. Apart from Hidegkuti, all the Hungarian stars played for the army team, Honved. They’d therefore been familiar with one another for a long time, and by mutual agreement played other sports together as well, to make themselves stronger and fitter. A veritable communist utopia on the pitch.

Unsurprisingly, the Hungarians notched up seventeen goals in their first two matches at Switzerland ’54, the most significant being the 8-3 win over Germany, with Puskas out injured. When the two sides met again in the final, there couldn’t have been anyone who expected anything but a win for Hungary.

What did Germany use to deny fate? The same quality they’ve always had on the pitch: the capacity to transform their suffering into epic feats. Their captain, Fritz Walter, was a thirty-three-year-old veteran with a fear of flying. He’d been a parachutist in the war and had watched his best friend die in front of him. He led a handful of younger but just as ruined players.

The trainer, Sepp Herberger, was one of those profoundly rational eccentrics that Germany produces every now and then. In the first match against Hungary he’d sent out a surprise team, as though, defeat being inevitable, he wanted to save his first eleven’s energies. Everything he said, though, contradicted that idea, which, when it came down to it, was actually a kind of praise. Each time he was asked about the fate of a certain match, he would answer in the same way: “The ball is round.” As though it was all down to chance, or the will of God, once the whistle blew.

Puskas was carrying an injury, and there was a lot of speculation about the unlikelihood of him appearing in the final. The Germans, in a move many interpreted as advance capitulation, offered to lend the Hungarians their doctors—which the Hungarians haughtily refused.

Herberger’s great spark came on the eve of the final. In that hoarse, slow voice of his, the German trainer explained that in normal conditions the Magyars would be superior, but that if it rained things might be different. As Victor Hugo said of Napoleon, Waterloo was lost because the rain prevented him from using his artillery so well and stymied his painstaking cavalry charges. Bad weather favors those who can adapt to mud and disorder. And when Herberger felt the first drop of rain, he knew the final in Bern was going to be an episode of trench warfare, a chance for the courageous to win the day.

Let’s cast our minds back to the most famous about-turn in history. No final had ever bucked expectations like this one was about to. Hungary scored two goals in eight minutes—unsurprisingly. Fritz Walter got his team together and said some words that no one else heard and that were never known to anyone besides them. What could this man—who only had to hear a jet engine to fall to pieces—have possibly communicated? What was contained in his agonizing dispatches?

The film The Miracle of Bern describes the numerous expectations unleashed by the match: for some it was verification of the German disaster after the Nazi delirium, and for others a recuperation of the nation’s joy. It had begun badly, but everything was about to change. It was also around this time that the England striker Gary Linekar was born, and as he would later go on to say, “Football is a simple game. Twenty-two men chase a ball for ninety minutes, and at the end, the Germans always win.”

Had they played ten more times, Hungary might have won nine times against the Germans. But it was raining that day, and Germany knew how to make the most of a difficult situation. The final ended 3-2, with the tragic kings of the spherical lifting the cup.

Let’s pause a moment and consider a concept that takes in a history of national mentalities and perhaps even the transmigration of souls: tradition. Some teams always lose in certain stadiums for the simple reason that they have always lost there. Little matter if they show up undefeated and with a guy leading the line wearing golden Nike boots. The rigid determinism of footballing traditions can be quite overwhelming. All the players who lost on the previous occasion can have moved to other sides or retired, but the new representatives of the team are wearing the same shirt, and tradition is going to step in and, without fail, snatch the ball from them at decisive moments.

Such myths do sometimes come tumbling down, but football’s ghosts aren’t overcome lightly. Something along these lines happened in 1974 and 1978. In the Germany World Cup, Holland played wonderful football but lacked the tradition a team acquires by swallowing bitter pills. West Germany’s play was encumbered, predictable; they lost against East Germany, just about beat Chile, and felt under huge pressure from their fans, who were desperately casting around for reasons to feel pan-Germanic. Success seemed unlikely. But they were supported by the many long shadows of those who had suffered in the name of the team. Their captain was Franz Beckenbauer, the young libero who had dazzled in the 1966 World Cup in England. Never has a player had better posture than Beckenbauer or been able to run so menacingly without the ball at his feet. When Heidegger, who knew nothing about the sport, went to a match, he was astonished by the determination shown by a young player, one whom destiny would later smile upon: it was of course none other than the player who came to be known as “Der Kaiser.”

In the two previous World Cups, the captain of Germany had had his fair share of heartache. In 1966 he saw the trophy stolen by a phantom goal (the Soviet linesman who gave the goal later confessed that body language affected his decision: the German goalkeeper looking crestfallen, the English striker wheeling away with his arms in the air; the symbolism signifying “goal” was so familiar to him he accepted it as a substitute). In Mexico ’70 he’d been on the losing side in the “game of the century” against Italy—he’d played with a dislocated shoulder, held in place by a bandage from the Great War.

In contrast, Holland was a happy bunch. They drank wine, smoked a cigarette or two at halftime, and were allowed visits from their girlfriends or wives (sometimes their girlfriends and wives). The Germans arrived in the final as though they’d been transported to the Russian Front. And won, naturally.

And what about the ’78 Argentina side? In front of their own fans, they lost against Italy, and then stuffed Peru with what seemed suspicious ease. But they were representing the country of Di Stéfano, Sívori, Pedernera, and other geniuses who never won World Cups but should have. Menotti’s men were carried along by debts accumulated over various generations.

There’s no way to calibrate the historical suffering that unbalances two matches. If a defender suspects his wife of having cheated on him with a friend while he was staying at the team hotel, the suffering is real but not of historical proportions. The following day he’s going to score the most superb goal. Whereas the pain of those previously in the same situation becomes even stronger, because it’s a compound of a long history. The great revelation in the film about King Pelé is to do with the moment when he, as a boy, listened to the 1950 final on the radio, bearing witness to Brazil’s defeat at the Maracaná. It was out of this fissure that his will to win the trophy three times was born—it was the same trophy he’d felt the loss of as a child.

But then, how difficult to make Holland even care! In the 2000 European Championships, they were the continent’s best-shaved team. They were on home soil, so the stands filled with their joyous trumpeters. Patrick Kluivert missed two penalties in a single match, and the cameras showed only a blissful smile on his face, like he was attending a country fair. Proof of how minor the repercussions are of being pole-axed in the Low Countries.

But let’s not make this an encomium to disaster only; it’s just to point out that in Brazil the equivalent would have sent the priests out to decapitate chickens by the thousand and disabled people to throw themselves into the sea in their wheelchairs. The only time Holland will win the World Cup is when they are a less happy country and allow themselves to feel the effect of complexes and frustrations from which, to date, they have been blithely disconnected.

BEAUTIFUL DEFEAT

A sense of the tragic can be remarkably helpful, and yet football also sometimes resembles a ranchera, the ubiquitous melodramatic Mexican folk song, and the best thing to do can be to simply feel outraged, singing, “How could we lose like that?!”

The Frenchman Christian Karembeu, who played a costly second-string artist at Real Madrid, would magnetize all the camera flashes as the team left the pitch; something in his face matched the epic anguish perfectly, the sense of a leader dethroned. Karembeu was one of those giants of the game who seemed subject to the judgments of destiny rather than the paying public. Obviously his capacity for looking so damned, but at the same time so damned good, was of more use to photographers and journalists than it was to the club.

Others capitalize on tragedy even more effectively. The Portuguese goalkeeper Vítor Baía was an elegant cultivator of his own indifference. Like those happy Dutchmen, the ex-Barcelona keeper poured most of his energy into sculpting his facial hair: his sideburns could have been Dalí’s handiwork. Perhaps it was because he hailed from the country of saudade that his melancholy manner was able to reach such splendorous heights each time he conceded a goal. Not much help in winning matches, but his chic outward shows of distress did at least ensure the reputation of this sublime martyr.

Baía’s crepuscular abilities can perhaps be extended to his country too. Every time the World Cup comes around, Mexican commentators go crazy for the Portuguese side, one of the reasons being that we would love to be able to lose like them. They manage to play amazing football for a couple of matches, and they even produce goal-scoring defenders. And they’re good-looking in an interesting way. They have the mien of those for whom things have not gone well but who are ready (with our support) for a swift turnaround. Unfortunately though, come game three, without fail they’re hurling abuse at the ref. It’s hard to find a national team that feels so little responsibility for their defects. Reporters, drawn in by the charisma of the Portuguese, go along with them for longer than you’d usually expect and try to find very strange ways to explain away their tendency for such elegant collapses. The Lusitanian rejection of success reached its zenith in the 2004 European Championships, which were held in Portugal. One local journalist summed it up perfectly: “Our players are completely lacking in vice: they don’t smoke, they don’t drink, and they don’t perform either.”

So great is the Portuguese players’ dedication to art for art’s sake that their faulty touches in 2004 could be seen as a paradoxical kind of efficiency. No one expected them to the reach the final, where they met a Greece side that had been transformed by the disciplinarian Otto Rehagel into awkwardness itself. Football was on Portugal’s side, but so was their propensity for sorrow. And true to themselves, they let the trophy slip through their hands. We Mexicans became admirers once more, knowing we’d never lose with such style.

Colombia has also done their bit for the psychology of defeat. Pacho Maturana’s side beat Argentina 5-0 on the eve of the 1994 World Cup and looked sure to go on to greater things. For the previous four years they had been a well-choreographed threat, with the shaggiest hairdos and the sparsest beards, a disproportionality in the hair department worthy of musketeers or pirates. They also had a number of black players who would seem to be wandering around asleep, before suddenly sprinting a hundred meters in record time. The team’s guiding lights, Higuita and Valderrama, belonged to that class of Latin American who need a little injection of angst before they can show they actually care. Both were so utterly self-assured that when a match kicked off it was as though they’d just finished one. It took such effort for them to even get on the field of play that there was no way they were then going to submit to everyone else’s rules; they attempted perilous and pointless moves simply to demonstrate how abysmal the necessary ones are. Never has a goalkeeper transmitted such self-satisfaction as Higuita as he rushed from his area to clear the ball, as though he were in some barrio alleyway, or when he did one of his famous scorpion kicks, clearing the ball off the line in the most audacious way. For his part, Valderrama embodied a phrase given to me by the poet Darío Jaramillo Agudelo: “We play wonderful football, only in slow motion.” To have a midfielder who was never in a hurry wasn’t entirely opportune, considering this is a sport where his opponents did run. His equanimity was a question of principle, and his calm was superlative when all about him were losing their heads. Valderrama would have been able to get annoyed with the firing squad when they raised their rifles; the sentence would have been annulled.

Colombia played in 1990 and 1994 as though they had a license to lose. Which made them different from the great Peru side of Mexico ’70 under Didi, who also played with a fearless optimism but gave everything until the final whistle to win. The Colombians operated with a kind of consummate playfulness. They ruled the scoreboard, even if the result went against them. No one ever beat them; they orchestrated their own downfalls. In contra to meritocracy and the vulgar customs of winning, the great Colombia side of those four years showed that the outcome was a highly subjective matter. Masters when it came to straying from the accepted path, they would never debase themselves by worrying about success. Higuita would take a free kick and have to dash back to his goal faster than his legs could carry him. And yet the danger of a counterattack was always pleasing to him.

The Colombian prodigies never wanted any other prize to come their way. Has there ever been a more Latin American feat than that of these buccaneers, masters of rebellious dignity, when they put on a show and didn’t worry about the prize?

So Colombia was the greatest proponent of a tendency we admire, without ourselves ever having mastered it. The Mexican national team’s war cry translates as “Yes, we can!” Since we expect defeat, it isn’t enough to tell our players we love them and that they’re great; it’s imperative we make sure they understand that there is actually a chance they might win something.

PRETEND PASSION

There’s such a range of behaviors on display at a football pitch, there’s no way of codifying them, above all because many are so hypocritical. An arena where pure ego dresses up as humility and consummate skill is employed to cheat refs, this game is dependent on acts of simulation, some as naturalistic as that of the Chile keeper Roberto Cóndor Rojas in September 1989. The stage was the Maracaná, the opponent Brazil, and the aim to qualify for Italia ’90. The Chilean number 1 went onto the pitch with a razor blade hidden inside one of his gloves. Seeing the unlikelihood of Chile coming back after Careca put Brazil ahead, he waited for a firework to pass close to his goal and, when nobody was looking, sliced his own forehead with the blade. When the referee came over, Cóndor Rojas claimed the firework had hit him. Though the scoreline would remain the same even if the game were abandoned, if they could prove that the game shouldn’t have been played under the circumstances, they’d be able to go to the negotiating table. The strangest thing about the tale is that Cóndor Rojas ended up confessing. FIFA suspended him from professional football permanently.

I met a man a few years ago who had died two hundred times. He worked as a body double in narco movies and in the occasional Western filmed in Durango. He was an expert in falling down stairs and off balconies and in being run over. He retired with a bad back, and the painkillers he took gave him an ulcer—a pretty decent trade off in his line of work.

He was a specialist in dying photogenically, which would have made him very well suited to being a footballer. In no other sport do you come across such extreme levels of histrionics. Suddenly a striker is flying through the air, coming to ground after a spectacular pirouette, flailing on the grass, hands to face, convulsing, all in the hope of a red card for the tackler, or at the very least a yellow.

What next for the athlete of the death rattle? On come the medics with the sponge, the bottles of water, and in a matter of seconds he’ll have recovered, the damage no greater than some wet hair and an untucked shirt. Like an amphitheater of resurrection, football offers the spectacle of the dead not only returning, but running. And it’s easy to tell when someone really has been hurt, because they lie there doing nothing.

Simulation is common practice. Referees can watch matches on TV as well, so they know who the divers are and sometimes don’t even award them free kicks when they are actually fouled. And when that happens, the censure the player receives, the whistles, howls, and boos, seem to contain the pride of unmasking not just one, but a hundred boys that cried wolf.

You could never imagine the batter in a baseball game throwing himself to the floor and pretending that the pitcher had thrown an invisible ball; in American football, you’d never get a quarterback halting his run to make out that someone had treated him “too rough.” Only in football do we find these fabricated fouls. This is partly because the refs and linesmen make more mistakes. If a player is sharp and particularly mischievous, he can get one over on the man in black whose grueling task it is to keep within viewing distance of the action.

There was a contretemps in France ’98 that summed up perfectly the power of pantomime. Diego Simeone, the Argentinian who had been the very symbol of fortitude in his club careers with Atlético Madrid and Inter Milan, demonstrated his love of the limelight in the match against England. The encounter between the two nations had been so hyped you’d have thought the fate of the Falklands hung on it. The first half exceeded all expectations with an epic, hard-fought 2-2, including a goal from Michael Owen on his national debut. But in the second half David Beckham had a run in with “Cholo” Simeone; sprawled on the floor, Beckham kicked out, discreetly but clearly intentionally. Up until this point, the affair had been governed by the quarrelsome logic of the animal kingdom, but then came Simeone’s Elizabethan revenge: Cholo collapsed on the floor like a skewered Mercutio, a display that turned what should have been a yellow into red. A couple of years later, Beckham’s Manchester United met Simeone’s Inter, and the Argentinian held up his hands to the deceit. If a hardworking battler like Simeone sometimes plays the comedian, it’s fairly obvious what’s going to happen with players whose only recourse is to theatrics. Like the film double with his two hundred deaths, certain footballers make a living from dying, but not really.

THE NEED FOR SPEED

As the name suggests, Nandrolene is an untrustworthy drug, one that makes you run faster but can also cause liver cancer. No one takes it for the nice taste. But sometimes representing your country means traveling from Australia to Korea, and from there to Texas, and somewhere along the way someone giving you a chicken that’s been pumped full of hormones. And if you end up being chosen to urinate in a bottle after a match, suddenly your career is in danger.

There has, it’s true, also been the odd case of athletes drugged not by unluckily consuming some triple-continental chicken breasts, but by the physical trainer! Pep Guardiola, at the time Barcelona’s model captain, was on the wrong end of a dope ruling in Italy. The impression the fans had, in this case, was that something had gone wrong on the game’s pharmaceutical front and that the problem must have been the doctor or doctored lab results.

Some therapists are convinced that the player needs support on two levels: the muscular and the spiritual. The second is obviously more slippery. It isn’t easy consoling a homesick player, or one who doesn’t know why he’s sick and whom you find staring at tables as though they were the league tables and he’s about to get relegated. Here’s where motivational patches come in. Footballers breakfast on the kind of pills you’d expect at an astronaut’s banquet. Not all of them are vitamins; some are antioxidants, and others help bring down swelling—the last kind decides whether the doctor keeps his job. When they claim that doping doesn’t help you to play like Maradona, it only means that the stimulants in their prescriptions are harder to detect.

Multimillion-dollar businesses hang on the fortunes of modern football teams, twice a week. This has made for severe tensions between the use of chemical remedies and their possible discovery. Energy boosters are the superstitious laboratory expedient in an activity that requires Rivaldo to be able to run very fast on Sunday, though he has been walking for the last year as though he just stepped on a cactus. For elite sides, these tonics are like life after death; it’s worth believing in them, just on the off-chance they happen to be efficacious.

No team is free of pills or physiological paranoia. To fend off a world that can force them to urinate at random any given Sunday, squads get together in five-star prisons where they eat closely guarded veal cutlets. And there, the boredom they endure has the same effect on the soul as doping does on the heart.

PASSION INHIBITORS

The fear of sexual contact is just as great as the fear of rogue pharmaceuticals. It’s not unheard of for coaches to send out flotillas of prostitutes against the enemy hotel. Before unleashing his forces, he gives them the team talk: the idea is not to satisfy the opposition, but to submit them to a grueling, porn-film kind of discomfort, reducing them to scraps of men.

Such exhaustion can be avoided if you allow conjugal visits. But when it comes to football, everything is almost entirely metaphysical. Though you get some permissive clubs (almost all of the Dutch and the Scandinavian sides), many of the physical trainers prioritize a certain conventional wisdom, secure in the certainty that any player who ejaculates on the night before a match loses the desire for the transcendent orgasm substitute that is the goal. The erotic is just as much part of dietary control as boiled vegetables.

Enduring all of this is nothing compared to the regular torture players have to endure, all the hours of doing nothing, nothing, and more nothing. When a team goes away together, what they have in common is the shirt, and the timewasting. When Ronaldinho plays his beloved Nintendo he likes to pick… Ronaldinho! Unfortunately not everyone can revel in such self-referential delights. Some get by playing cards or staring at the ceiling. These prolonged hotel nirvanas have the capacity to erode the brain imperceptibly, to the point that players might actually end up botching the job come match day, or say yes to appearing in advertisements for talcum powder.

The solitude of team get-togethers is extreme, because it is, among other things, a shared solitude. Your children turn into the photos printed on the T-shirt you sleep in; in contrast, your roommate is a smell too near. Even clubs who provide their players with Armani suits force players to double up in rooms. The rigors of personal branding are nothing compared to this forced cohabitation. I once asked a professional football player what he and his roommate talked about. The answer gave a glimpse into the rich world that is psychopathology: “He doesn’t talk to me,” the player said. “He talks to his penis. He calls it Ramón, and they talk about everything they’ve been through together.” I wasn’t surprised when, a short while afterwards, the player in question—a courteous and calm individual who humbly used the word “penis” when talking to a journalist—was warming the bench. His roommate’s monologues to Ramón had had their effect, and he started seeing things on the pitch that weren’t there.

A football player has to combine the narcissism of someone who wants to be seen at all costs, the vocation of a monk to be shut away in a monastery, and the ability to put up with the stench of the fellow inmate. Has any person ever been born with such a combination in their nature?

While the stars wander zombie-like along the hotel passageways, there we are, the fans, speculating about what they’ll do on the pitch. Their isolation opens a gap for prophecies to fill. Words either rush into football’s “empty” hours, or prove that players are made of such stuff as boredom is made of. We talk about what we cannot see. And then when we have the match there in front of us, we begin to talk about what we do not understand.

THE APPEARANCE OF THE INVISIBLE

A football pitch comes with whole basements full of superstitions, complexes, phobias, dramas, and dreams. What else but the most indeterminate and obscure reasons could explain the goal drought suffered by Fernando Morientes, the nullification of a player whose only quality was his efficiency in front of goal? And why, when he finally did score again, did he push away Roberto Carlos when he tried to celebrate with him? It was as though outrage was all he deserved, or as though he had only become himself again so that he could take revenge on his own team, not on the opposition. Did that gesture mean that even scoring couldn’t make him feel right at Real Madrid? Had he spent so much time on the bench and playing out of position that his emotions themselves had been dislodged? Were his thoughts drifting towards another club already, one where he could play without the obligation of being a genius?

They wouldn’t be mysteries if they proffered up their own answers. We can know that Morientes left Real for Monaco, but we’ll never be privy to the agonizing that went into the decision, because, among other things, the player himself can’t understand the tangle of emotions that prompt him to pack his bags. The exterior in football is so pleasing, so flashy, that the private life of goals gets obscured. And yet there are inner causes.

The strip between the pitch and the tunnel down to the changing rooms is called the “mixed zone.” It’s the closest the press can get to the facts. When the time comes to make a psychological evaluation of the game, there’s no mixed zone for all realities and desires. The mind is also in play, but we’re almost always unsure of its precise function. Such lack of definition only adds to the interest in a sport in which the great moves have their beginnings long before they become visible.

Football’s attractiveness lies in its constantly renewing capacity to make itself incomprehensible. Something occurs but we don’t understand it—like grass growing, or the blood pumping around and around. Zidane suddenly happens on a gap and plays the ball into it. What moves him? What idea, as yet uncertain, crystallizes in this forward movement? Without knowing the way it’s going to go or how it’s going to end, we feel the vibration of what might happen and, though not yet here, is already of consequence. Zidane moves forward. The invisible is the one thing we can be sure of.

2. MENTALITIES

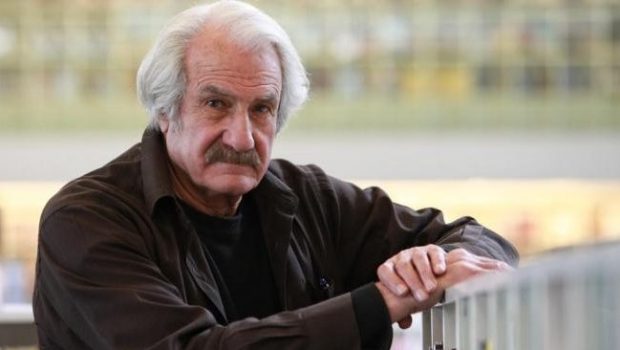

JUAN JOSÉ ARREOLA, PING PONG HERALD

I once tried to get onto the Mexican ping-pong squad. This was in June 1970, two years before the Olympics came to Mexico, and even minor sports had suddenly taken on a mythical glow. I was fourteen at the time and had developed an interest in the games played in the kitchen-dining room of the writer Juan José Arreola; he’d installed a ping-pong table with a Chinese-lacquer top to ensure the perfect bounce.

Arreola was forever moving house but always stayed on the outskirts of Colonia Irrigación. (“I’ll change rivers,” he’d say, “but not to Mesopotamia.”) At the time he was living on a street named Río Nilo (River Nile) and had developed an interest in the building of the Aswan Prison, on the other Nile, as though those dykes had something to do with the traffic coming along his street. I was quite defensive as a player, and he encouraged me to try a contentious shot that involved slicing down across the ball: “the Aswan Dike,” he called it.

Every Saturday Arreola’s apartment was divided between those of us who leaped around after the ping-pong ball, and the sedentary ones who played chess at the back, clouds of billowing smoke around them. There was barely any furniture in the place, which resembled a cross between a barrio social club and a salon for intellectuals. When the Maestro got hungry, he went into the kitchen and opened a bag of crisps. This meager fare he accompanied with careful sips from a silver hip flask that he kept in his jacket and never once allowed me to taste.

During our sporting marathons, the author of Confabulorio would go from room to room reciting poems and sporting facts, eyes bulging, his gray curly hair a tousled mess.

Arreola had retired from his work as a mime artist, actor, artisan, cloth seller, and prose writer of Borgesian refinement, and his approach to sport was as an extension of words. He was more a herald than a reporter—a fanciful town crier. He spelled out what might happen in the matches, not deigning to describe the precariously real shots themselves. Extremely thin and extremely sprightly, he could get the heel of his foot up over his head, fakir-like. There was a theatrical liveliness the way he walked, and he often went around in a frock coat that he claimed had belonged to José María Pino Suárez. He always moved somehow rapidly, putting me in mind of the Yamaha he kept on the lower floor and drove to University. All of this was long before television would devour the immense orality of the long-winded mass of Mexican writers. These Saturdays of ours, Arreola would foretell the outcomes on the ping-pong table and the chessboards, using the suggestive phraseology of the fortune teller to prophesy the outcomes.

Though his technical understanding was very good, his advice always tended towards the metaphorical. When I took part in a city-wide table-tennis tournament, I was drawn against a formidable opponent in the first round, a player who could hit the ball in a way altogether contradictory to his first name: Modesto. He worked as a Metro driver, and similarly in ping pong he evinced the kind of sureness that made it seem he was on rails. I was a newcomer, my only strong point was my determination not to give up. When I told Arreola I was playing Modesto the thunderer, he pronounced these words: “Get him inside your chicken coup, and he won’t be a peacock anymore!”

I lost badly but never forgot the phrase. All sports owe something to the words that go around inside the players’ heads. Certain expressions have the capacity to activate the mitochondria, prevent tiredness and sweating, keep you motivated in spite of adversity, and drive you on to win a trophy, that mysterious object that as an object is never much to look at but that everyone still wants to get their hands on. Arreola’s pessimistic cries were more literature than strategem, but they showed the intimate connectedness of physical exertion and the imagination.

Can the interior life of a sportsperson ever be fully calculated? The first response to a metaphysical question like this, is that different sports mean different thoughts. I put ping pong forward here as a contrast to football.

The games played in Arreola’s apartment were meant to pass the time. Things were completely different when I went to the Mexican Olympic Center to ask to join the table-tennis team. I met Nobuyuki Kamata, a coach who had recently arrived from Japan, whose ideas about the sport were inflected by Zen philosophy. For Kamata, the sportsperson who knows how to concentrate can suppress the interior monologue and thereby pull off shots with a kind of automation that is alien to the nervous system. “He who thinks, loses,” was Kamata’s motto. Like the archer who unlooses the perfect arrow without being able to see the target, the ping-pong player, emptying the mind, ought to allow his hand to decide. To blank out the interior world like this requires monk-like discipline—something I was incapable of, whereas my sister Carmen mastered it, going on to become a national champion and even traveling to China. There she got to play some true experts in the art of operating at the margins of thought.

Ping pong is nonstop, a reflexive parenthesis, which is the reason why thoughts need to be dispensed with. In such rapid-fire territory, everything depends on instinct and reflexes. “He who thinks, loses.”

Strangely, Arreola’s view was that football was a less intellectual sport than tennis or ping pong, due to the lack of the intermediary racket. Its actions are grosser, in that they do not pass through a civilized instrument, and furthermore bypass the hands, a fundament of human culture. Tennis presupposes more complex historical developments; the scoring system is complex, and the rackets are testament to the kind of industry and ingenuity that get the best out of catgut.

Arreola was an admirer of sports that filtered through technology and craftsmanship. He was captivated by the supersensitive oilcloths used on the Swiss paddles in ping pong; by the East/West division of the sport depending on how a player held the bat; and by the unassailable superiority of the Chinese lacquer. Though he was born in Jalisco, the cradle of Mexican footballing culture, the beautiful game struck him as regressive, a backwards step to the days of mankind before tools.

Faced with Arreola’s eloquence, there was nothing I could do to argue football’s case. But in the same way that we true fanatics carry on arguing even once our interlocutor has gone away, I’ll give the answer I was unable to give at the time. Football offers one of the most propitious situations for the intellectual life, in that the majority of the game is spent doing nothing. You run but the ball is nowhere near you, you stop, you do up your bootlaces, you shout things no one hears, you spit on the ground, you exchange a harsh look with an opposing player, you remember you forgot to lock the terrace door. For the majority of the game, the football player is no more than the possibility of a footballer. He or she can be in the game without being in the game. He or she has to be there for the group sketch to be complete and has to move around to avoid being caught offside, or to shake off a marker. But there are long stretches inside this strange state, being-nowhere-near-the-ball, since it’s in only the zone immediately around the ball that the game truly takes place.

What this means is that the player spends his time thinking about what he or she should be doing on the pitch, or about utterly unrelated subjects that nonetheless affect his performance. The goalkeeper, the great loner in the contest, has more time than anyone to reflect, which is why thinkers and eccentrics tend to gravitate to the position, the leaders and the clowns. All keepers know the rich interior life their profession entails. Constantly on guard, long periods pass with nothing to do, and yet, at any second, they might be called upon to make a save.

It could be that, to Arreola, an interior life of this kind seemed too bucolic, however this is the nature of the symposia that take place on turf.

MILOŠEVIĆ, SLOW SPRINTER

One of the most astonishing performances I have ever witnessed came from Savo Milošević in a 2005 match between Real Madrid and Javier Aguirre’s Osasuna. Milošević was playing for Osasuna, and they were away from home. Osasuna went a man down, and then Valdo had to be stretchered off after a brutal tackle from Roberto Carlos. The rojiblancos had arrived at the Bernebéu on a high, second in the league, but everyone knew that the Basque club, run on a shoe string, would go to pieces come winter, like the horses of old that failed to make it to the racing track. What chance did their ten men have against star-studded Madrid? Milošević played in unusually inspired fashion, trying to get his teammates to simply play keep ball. For most of the game he passed forward at the same time as sideways—sounds contradictory, but far from it; the veteran moved like an old, whipped nag, but carried on with his chess knight-like moves. He held onto the ball, infuriating the opposition, and then suddenly finding a hole in behind. The Bernebéu got to its feet to applaud him when he scored a header—by no means his specialty. He’d single-handedly unhinged Madrid, so in a sense it wasn’t a surprise that he should decide the contest. In a match dominated by Milošević and his sangfroid, his ability to put the ball to sleep, Madrid equalized through sheer weight of numbers. You’ll never find it taught in any manual, because it’s a trick that can’t be programmed. Basically all manuals ought to begin with the following phrase: “Football is too strange to predict.”

Milošević put into action the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise. Extremely slow, sure of his movements, there was no way he was going to be caught by speedy Roberto Carlos. That night made me remember Arreloa’s words: “Get him inside your chicken coup, and he won’t be a peacock anymore!”

ENOUGH, FOOLS

Jorge Valdano recovered one of football’s essential anecdotes. In 1969, the Argentinian side Chacarita Juniors won the league against all expectations. A humble side, when they came out of nowhere to top the league they were coached by a man who spoke as resoundingly as his name suggested: Geronazzo. When they asked him how he did it, he said, “The first time I saw them play, I said to myself, ‘No team can win if more than thirty percent of them are simpletons.’ I lowered that percentage, and we won the league.”

Foolishness, in football, may not be abused. Every team, as representatives of the human condition, has to include a couple of dummies. It isn’t that every midfielder needs a mind like Jules Verne, but he does need to move the ball in accordance not with what is happening, but according to what might happen. What disgintuishes illustrious players from the athlete forcing himself to compete is that their prodigious acts only become possibilities in the moment when they occur; a second earlier, they were impossibilities.

The beautiful game involves skipping around, tugging shirts, and so on; it is a mechanical activity. But the decisive factor is the ghostly feint, the pass that makes a co-conspirator of a gap, the ability to distress and send your opponents the wrong way, winning the ball back after you’ve seen what an opponent has in mind, anticipating hidden intentions.

Can a football player have such potency? Truly, this is no game for buffaloes. If a person spends the best part of their youth lounging in a hammock, it’s highly unlikely they’re going to be turning out in the shirt of top-flight sides in later life. But genius inside a football pitch is another thing, determined by an attribute just as singular as paranoia, melancholia, or a sense of humor.

As Woody Allen tells it, Abraham Lincoln was very pleased when, one day, he was asked, “How long should a man’s legs be?” It gave him the chance to deploy the obvious little apothegm “Long enough to reach the floor.” It is with the same irrefutable common sense that we can state that a player is in good physical condition if his merits outweigh his tiredness. That is all.

You don’t learn to be a trickster in the gym. The contract between man and ball is psychological, and surpasses mere physical effort. You can’t have an amazing shot without two interior attributes taking pleasure in shooting and wanting to get better at it. This is the only way to explain the maniacal obsession of those who teach their feet, as it were, to speak many languages. How different a pile driver is from a volley off the instep or a shot off the outside of the foot!

Clearly, not all kinds of intelligence are useful in football. A strong capacity for abstract thought is in fact calamitous with a ball at your feet. What football demands is a mind so quick and self-assured that it meshes with physical reflexes, though it isn’t precisely the same thing, as it presupposes a sequence, a next action, something still to come, when the move will make better sense. Romário, with three defenders surrounding him, in the blink of an eye would discover a way through them. He was one of the very few with the ability to drop a shoulder so confoundingly, showing the balance of a tightrope walker as he left the opposition in his wake, and the nerves of a war correspondent as he put up with the attentions of his man-markers, and, ultimately, making the impossible space possible.

HOW TO BE HAPPY

Almost always, a goal is followed by a group hug and everyone trotting back to the halfway line. Sometimes the celebration gets skipped, say, if the team is losing 5-0 and the goal is a consolation—“consolation goal” anyway being a misnomer, because it only shows how much better the losing side could have played. Sometimes the celebration is a solo performance of jubilation—Paolo Rossi sliding along on his knees, Hugo Sánchez’s somersaults, the outstretched arms of Careca wheeling away like a crop duster, Bebeto’s imaginary baby in the cradle, Cardozo with his boot to his ear, like Super Agent 86’s phone. In Nuevas cosas de futbol (Football’s New Things), the Chilean reporter Francisco Mouat creates an unforgettable typology of goals, with forty-six examples of celebrations—all these different ways of transmitting on-pitch delight to the fans—to match.

The people in the stands have found themselves perplexed by the ever-wilder post-goal displays, and how they come increasingly to occupy center stage. The celebrations of players with carnival tendencies can become more involved than the goal itself. With a dynamism he has never showed inside the game, a poacher who has just bundled the ball past the keeper from a few yards out might run all the way over to the cage keeping the ruggedest fans off the pitch and leap up onto the bars. Whereas Hristo Stoichkov tore apart the widest array of defenses without showing the slightest emotion—aside from the intense grimaces that communicated his dislike for his rivals and, even more, for his teammates.

Mouat’s typology includes “the dog”—a celebration once carried out by Cuauhtémoc Blanco. It was so filthy that it won him a booking, and it became one of those things you can’t help but remember, little as you wish to. Blanco and a certain goalkeeper named Félix Fernández had been longstanding enemies. The contrasts between the pair were obvious, Blanco being a sewer rat, advancing along the pitch like he was keeping an eye out for a car mirror to steal, his shoulders hunched, his gait duck-like. He always had a mean look about him and would have tantrums that infuriated referees as much as they softened the hearts of telenovela actresses. He was the Mexican player between 1995 and 2005. Félix Fernández, on the other hand, willowy, always wearing those white gloves, is Mexican football’s cultured man: a great columnist, involved in social work, a philanthropist who also liked to have a good time. Blanco perhaps felt him to be his enemy because the keeper was the paradigm of all the virtues favored by his parents, teachers, coaches, as well as the refs and linesmen who constantly berated him. Then one day fate pitted them against one another in the most direct way: a penalty. Cuauhtémoc was up front for América, Félix was in goal for Atlético Celaya, and it was the forward’s chance to settle the score. Cuauhtémoc slotted it home, and then ran over to the line, got down on all fours, cocked a leg, and, doggy style, pretended to mark his territory.

A constant in great goals is the keeper beautifying them by diving uselessly to try and save it. In this case, Félix faced Cuauhtémoc with aplomb and, rather than reacting, merely turned his thoughts to his next article.

Cuauhtémoc’s celebration, like that of Hugo Sánchez when he grabbed his testicles, belongs to the eschatological kind of pride, and it isn’t difficult to see why it gets punished. But there are other expressions of happiness that disconcert referees, and sometimes even FIFA itself.

Forwards of a romantic nature never miss the chance to seal their goals with a kiss. This can please family members or nations in need of some supportive therapy. At France ’98, Rivaldo rained down kisses on his wife, and Zidane, Algerian by descent, kissed the blue shirt each time he scored—the most significant gesture of racial integration in the country in the post-war period, according to Le Nouvel Observateur.

Imagination, so often a deciding factor in moves on the pitch, also determines celebrations, and over-celebrations. There was a period when it became fashionable for the goal scorer to remove his shirt, baring underclothes with photos of the kids, a Madonna, or a “Save the Dolphins” message. This editorial variant on the celebration is the least spontaneous, as well as a good demonstration of why players are so rarely any good as journalists. As a way of stopping time-wasting and controversy, FIFA decided that taking your shirt off was punishable with a yellow card, and at times a fine.

Celebrating though you know you’ll be punished—that can be another way for the protagonist to prove his convictions. Batistuta dedicated a goal to an Israeli child who’d been decapitated. He knew he’d be fined for unveiling a picture bearing the child’s name, but he paid it very willingly. The fine was part of his gift.

Happiness, without a doubt, is a subjective thing. Some are very secretive in their celebrations, while others, though experiencing something trivial inside, dash off like they’re possessed, embracing the manager and knocking over all the water bottles in sight.

Unfortunately for the plurality of passion, football depends on certain rules and regulations. If things get out of hand, if players let their lambada last a little too long, they see yellow. Within FIFA’s urbane code, it’s looked down on for a player to exaggerate any feelings. Since it’s down to the ref to decide the sanction, some choreographed dances are punished like crimes of injurious theatricality. The Liverpool player Robbie Fowler was suspended for six matches for his drug-addict celebration: he pretended to sniff the goal line like it was cocaine. The most severe punishments in the game are meted out over what is essentially a question of manners.

Expressiveness has come under controls that are comparable in rigor to anti-doping measures. In its eagerness for players to set a good example, FIFA forgets one of the central aspects of happiness: it always manifests in exceptional ways. But rules are rules, and football players have no choice but to contain their joy in the same way they must hold themselves back if another player spits at them.

“THOU SHALT NOT KILL,”

AND OTHER EXAMPLES OF INTELLIGENCE

Sports psychologists say you should go out on to the pitch with a cool head. Rise above the heckling of the Milan tifosos, rise above what the Real Madrid forofos think about you, accept it when a perfectly legitimate goal is incorrectly overruled, put up with trash talk, pinches, and bites, as well as insults, the sweat or the saliva of your opposing number; all of these are minimum requirements, at times, if you want to avoid a red card. Truth be told, it isn’t easy to stop yourself from being violent when your blood is up and a stadium is rocking. To acquire the internal discipline you need to play the game, you’re really better off visiting Tibet than a training session.

The mind of a player is there primarily to keep him in check, to prevent him from murdering the defender who just very nearly broke his tibia. It can also be turned to more creative ends. Let’s consider two cerebral attributes that are necessary in the game: the capacity for pleasure and the capacity for mocking others. Great moves, whether by an individual or collectively, have no other motivation than the pleasure of making them happen. When a virtuoso like Hagi or Del Piero plucks a ball out of the air on the tip of their boot, they don’t have time to think about where their team is in the table or the professionalism incumbent on them when they don the colors; the impulse is dependent, in equal parts, upon a mastery of your own movements and the knowledge that you are being watched. Great players tease ovations from the crowd and make a mirror for themselves in the applause; acclaim is what they measure themselves by. The writer Osvaldo Soriano once visited the hotel where the Argentinian national team was staying, and passed by Maradona without acknowledging him. Could a reporter really ignore this, the greatest dignitary of ball control? No, not when Maradona picked up a mandarin and made a wizardly display of keepy-uppy, right there in the lobby. A smile spread on the face of the portly little diva when he saw he’d impressed the writer.

And what of the mockery of others? Deceit, the ability to trick a player, adds interest to a sport that would die if outcomes were foreseeable. A shimmy of the waist, the deadly pause, and the ball that swerves unpredictably in the air: these surprises are part of the essence of the game. The free kick can even be used to get one over on your opponent.

Usually, players take their heads with them when they leave the stadium. What this means is that they also have to use them in training sessions and on team trips. “Hell is other people,” said Sartre, who never even had to go on a team trip, didn’t have any children, and was never a member of a residents’ association. What would he have made of the young men forced to spend longer periods sharing a room with teammates than with their wives?

A player’s primary stat is how much he cost. There’s little point railing against the transfer market, which is a form of collective madness, nothing more or less. Plus the outlay for Robinho is immediately canceled out when the shirts bearing his name begin flying off the racks. The only thing upon which a value can’t be placed in this absurd emporium is the nerves of those directly involved in it. These you can’t measure.

The magic of football depends on cunning, a quality that resists all quantification. Suddenly, some slight fear enters the mind of the Balon d’Or winner, and his shot ends up in Row Z; moments later, some debutant who’s yet to sign a permanent contract, whose name nobody knows, forgets about his respect for the legend, and scores the kind of goal that makes people believe in the idea of glory as something improvised.

The war of nerves isn’t stipulated in any clause of any contract. It’s football’s gratuity, the only aspect where the titans of the game remotely resemble those of us who only ever participate in our minds.

3. GOALS AND TIME

In memory of Juan Nuño

Oh for a club that doesn’t cultivate blessed nostalgia.

NELSON RODRIGUES

In “Teoría de los juegos” (“Game Theory”), one of the essays in Veneración de las astucias (The Veneration of Cunning), Juan Nuño considers football’s temporal specificity. Certain other sports don’t have a time limit and can be interrupted by timeouts called by the coaches, like baseball and American football. Baseball has the most tremendous disdain for chronology: the nine innings can either be over quite quickly, or else last whole days. Like in the Odyssey, the goal is to make it home, but how long the journey takes depends entirely on the players’ reflexes.

A universal facet of games is the way they suspend the habitual flow of life; under the bright glow of the floodlights, pitches are subject to artificially made schemes and laws. In this capricious universe, football sets itself apart with this trace of unsettling normalcy; there’s no way of stopping the passage of time. “A football match is more anxiety-inducing, more dramatic, than any other game,” writes Nuño, “for the fact that time runs parallel to time in reality. The strong feelings generated by football are rooted in death, which, each time a human activity is time-measured, watches from its hidden vantage.” The passage of minutes outside the stadium coincide with those inside it. In American football, an incomplete pass means the clock being stopped; in tennis, when a tiebreak goes to “sudden death,” the contest can go on as long as the players remain tied. Whereas in the Maracaná time retains its insistent capacity to zero in on destiny. Not even a 0-0 will necessarily win you extra time. And only in exceptional cases, deciders in a championship or in qualifying, will a game be subject to the shock therapy of penalties or the “golden goal.”

The ninety minutes are in a way illusory: they cover the current episode in what is actually a vast genealogy of encounters. In his biography of Boca Juniors, when Martín Caparrós writes, “In 1933, we came in second,” in fact there’s nothing strange about the statement. Fans truly rooted in their club are integrated into its history. Caparrós talks about something that happened twenty-four years before he was even born, but it has a hold on him, with all the ghostly intensity of football’s traditions. The time to which the team is subject is the same time to which the spectator is subject.

THE SPEED OF MEMORY

Football nostalgia is always in a hurry. Félix Fernández makes the comment that among the things you lose when you make the move from amateur to pro, the most precious is the “third half,” which consists of drinking and remembering; the only thing better than seeing a goal is to play it back. In this period of extra time, passages of play expand and dilate as though Proust were in the dugout.

Memory certainly has the power to make treacherous blows even worse; sometimes the weight of memory is even enough to make a fan retire from the game. “December 19, 1971,” a story by the writer Roberto Fontanarrosa, has to do with one such extreme situation. Casale, an old man, has decided never to go and watch his team, Rosario Central, again; he’s on the verge of a heart attack, he can’t take the wringer they put him through anymore. When his team is playing, he stuffs his ears with cotton wool. He’s of the class of fans who will only let someone tell them the score if he has a tranquilizer in hand. But the thing is, Casale is also a legend in his neighborhood; when he went to the stadium, Rosario would win. A group of younger fans, innocent of memory’s terrible, lacerating edges, decides to kidnap him and take him to a match, like a lucky charm. The sheer joy of watching his team is too much for his heart, in both senses: he enjoys the match greatly, and when Rosario wins, he meets his double date with destiny, dying in a state of grace after helping his team to victory.

The fanatic who dies goes, as the Ancients put it, “with the majority,” which is the destination of all the best fans. If football is an activity that thumbs its nose at death—an imaginary lengthening of the passing of ninety otherwise implacable minutes—it should be assumed that the cheers of everyone who has ever cheered the team on continue to echo around the grounds. In the collection of newspaper columns by the Brazilian writer Nelson Rodrigues, entitled À Sombra Das Chuteiras Imortais, he puts forward the following necrological appeal: “No one can miss a Sunday at the Maracaná, and I also include the dead in this call; death exempts no person from their duties to the club.” Anyone who has ever heard the roar of a full stadium knows there are more voices than spectators; the ghosts come, too.