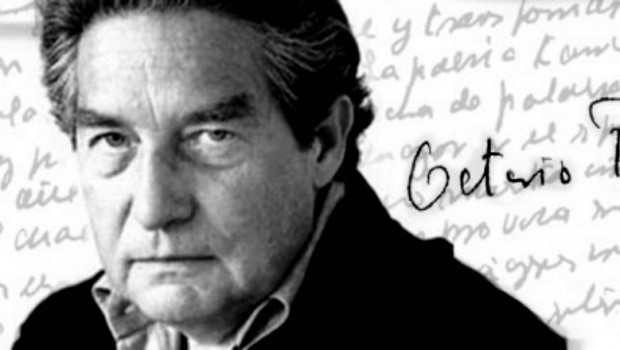

Killing Time

Tedi López Mills

…an atmosphere both dry and misty, tangled,

where the cigarette is always set diagonally from that which

continuously creates it.

FRANCIS PONGE

My tobacco smelled of a dark room with coal-dusted

furniture, in which a lean black cat

was stretching…

STÉPHANE MALLARMÉ

Out of my first cigarette, my first remembrance of memory was born. Beforehand, there are only bits and pieces: contradictory or truncated versions I’ve been told over time. Cigarettes represent the start of a dual vision: me, from a distant perspective, watching myself smoke, in this case. Outdoors at first, in a corner hidden behind foliage of some sort, lost in the closest thing to nature available near my home: the Arboretum of Coyoacán. There, at age twelve, I smoked all the brands I could clandestinely acquire during several intensive sessions: Raleigh, Kent, and Record. Once I was well within the habit of a pleasure that combined fear, dizziness, nausea and a gleam of adventure: Winston, Baronet, and long and illustrious Eve—back then, the feminine cigarette. My physical discomfort diminished with each puff, and in its place, a certainty gradually took shape that once I’d dominated the gestures—including that of repeatedly releasing smoke rings, as if the tenuous circles in the air were my own personal creation—there would be something more: life in its purest form, perhaps, without the third dimension of memory. And, paradoxically, without cigarettes either, because out of smoking another, even more extravagant vice had emerged: an obsession with quitting. The pile of butts in the ashtray stimulated this sense of purpose: the next cigarette would always be my last.

The attributes of this perpetually deferred quitting have multiplied since then. At this point, there’ve been cigarettes for almost everything: contemplation, expectancy, melancholy, reading, conversation, tedium, anguish, passion, hellos, goodbyes, commuting, travel, insomnia. Moreover, smoke has revealed its own selfsuffi cient landscapes—morally bearable because they are abstract, and somehow has become a persistent trait of the most minutely detailed, subjective passage of time: my cigarette lasts approximately four minutes and, according to the strict timetable I’ve imposed upon myself (starting at six in the afternoon), I have to abstain for 45 minutes before I can light up the next. Thus I’ve achieved the miracle of making my hours less than 60 minutes long and of having four minutes that don’t exactly count as time, but rather as its absolute alternative: a pause. That’s what Baudelaire was referring to, I suppose, with the phrase “They smoked cigarettes to kill time.” And perhaps that’s what Funes the Memorious’s endless cigarette meant; although in his case, it would also serve as proof that total recall doesn’t exclude the present: “He was lying on the cot, smoking. It seems to me that I didn’t see his face until dawn; I believe I can recall the momentary glow of his cigarette.”

I used to have a professor of narrative who’d censor me, because among his many rules on good writing, he’d posited one that was unbreakable: no characters smoking pointless cigarettes. Obviously, my teacher didn’t smoke; otherwise he would have known that the notion of a pointless cigarette, even a literary one, is inconceivable. On the other hand, we have the opposite complaint. In “For smokers only,” Julio Ramón Ribeyro states: “Writers, in general, have been and still are great smokers. But it’s curious that unlike gambling, drugs or alcohol, they haven’t written books about the vice of tobacco. Where is the Dostoyevsky, the De Quincey, the Malcolm Lowry of cigarettes?” Ribeyro proposes a few references: a phrase from Molière, Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain, Zeno’s Conscience by Italo Svevo—which, according to Richard Klein in Cigarettes Are Sublime, is vital to any “serious discussion of cigarettes,”—and subtly places himself at the head of this small line. From the beginning, his text clearly establishes the terms of his pact and his tribute: “While I wasn’t a precocious smoker, from a certain point forward, my story is interwoven with that of my cigarettes.” The confession begins in health and ends in sickness. And yet, Ribeyro doesn’t abdicate. After an operation in which they remove a section of his duodenum, nearly all of his stomach and part of his esophagus, he is obliged to check himself into a post-op clinic in order to learn how to eat again and, above all, how to live without tobacco. Just when he’s about to give in to resignation, or as he puts it, to unbelievable despair, he looks out of the window in his room and sees some construction workers on their lunch break at a building site. He feels a rush of envy; after a few sentences, things get worse: “…at the end of their meal, I saw them take out packs, pouches, rolling paper, and light up their after-dinner smokes.” The scene saved him: he finally understood that being cured was worthwhile, because one day he’d be able to smoke again.

Something similar happens to Hans Castorp, but it’s the other way round. When he arrives at the Berghof sanatorium, his waning health is somewhat reconstituted upon comparison with that of the other patients, particularly because he’s able to smoke: “I can’t understand it,” he says. “I’ve never been able to understand how someone can not smoke: it deprives man of the best in life…at least, of a first-rate pleasure. When I awake in the morning, it makes me happy to know I’ll be able to smoke all day and, when I eat, I look forward to smoking afterwards; I could almost say that I only eat in order to be able to smoke… A day without tobacco would be empty, insipid and of little use… If I had to say to myself tomorrow: ‘No smoking today,’ I believe I wouldn’t have the courage to get out of bed… I’d stay put.” But as his stay on the mountain is drawn out, Castorp sees his pleasure fade away: smoking becomes more laborious to him; it leaves a bad taste in his mouth. And this obligatory abstinence is the sign that he’s come down with the spirit of the disease itself, that he’s now a member of its sect: “exhausted and nauseated, I threw the cigar as far away as possible.”

Hopscotch ends with a cigarette. Oliveira asks for a light. Etienne remonstrates: “No smoking in the hospital.” But, “we are the makers of manners,” Oliveira responds, and then pronounces the last words of the novel: “Just let me finish my smoke.” Over 598 pages— in my edition—of the novel, surely La Maga and Oliveira smoke around 400 cigarettes between them, an anonymous brand at first which is transformed into Gauloise starting on page 155: “La Maga had lit up another Gauloise, and she was singing softly.” Cortazar’s “smokes”—unlike his jazz, or the turtleneck sweaters that are the uniforms of so many of his characters, or his eroticism restrained by the tutelage of love, or even of his almost earthly cats—are not mythical; they’re more like an inevitable condition: as if no act could take place without the corresponding smoke: “sitting on a pile of garbage, we smoked for awhile,” (this is the inaugural cigarette of Hopscotch); “…one left one’s wallet on the table, searched for one’s cigarettes, looked out at the street, and breathed in the smoke”; “against his face, he felt her cry with happiness that another cigarette had brought nighttime back to the room and the hotel”; “… Horacio oscillating rhythmically in tobacco… chatting up La Maga through the smoke and the jazz.”

All these cigarettes prove nothing except the simple fact that, faithful to their nature, they are accumulated. “Now that I’m old,” Zeno writes in his diary, “and no one demands anything of me, I continue passing from cigarette to purpose, from purpose to cigarette.” In his story, disease possesses the resistance of conviction, and smoking is one of its essential symptoms. Zeno tries to cure himself, but along the way, he discovers that there’s a pleasure more powerful than his dream of health: that of the last cigarette. “I believe… it has a more intense flavor. The last one gets its taste from the sense of victory over oneself, and the hope of a strong, healthy future close at hand.” Zeno smokes it throughout the book and only towards the end does he manage to free himself: “I’m cured!” Now all that remains is to die.

Out of superstition and likelihood, I don’t call mine the last, but rather the next-to-last. Among other things, I can prolong the effect of certain decisions that way. For example, not long ago, on a Sunday around midnight, I repeated once again the solemn scene of stubbing out my cigarette and promising some scant divinity that as of the next day, I would no longer smoke. I sustained myself in a limbo of pristine air for 47 hours. As soon as I felt it was possible to exist without smoking, I quickly lit up a cigarette. That was the first of my next-to-lasts. [2001]

Posted: April 14, 2012 at 10:40 pm