Addiction & Compulsion Body, Mind and Words

José de la Isla

Near the end of a seminar on addictions in San Juan, Puerto Rico, documentary producer Penelope Douglas cut into a presentation to make her point. Wake Forest University Medical School had pulled together journalists to provide them with the state of knowledge about addictions.

It’s not the nicotine in cigarettes that’s harmful to the body, Penelope, who had done extensive research on the topic, said. No one has ever died of nicotine. The other 400 ingredients in cigarettes are the harmful ones. Like so much in science the answer might be yes and not.

But new methods weighing and measuring our addictions, compulsions, and obsessions are now challenging previous assumptions. Eventually science might even encroach on an understanding into motives. This powerful mind-body research into addictions should give writers and creative artists a moment’s pause.

For me, it’s now three decades after I was part of trying to understand the illicit-drug world. I headed the first think-tank into the topic for a Washington, D.C. group known as the Drug Abuse Council. Back then, the scene was divided into law enforcement and treatment approaches as the two heads of the dragon. A dubious public policy intended to quarantine drug use. Now my participation here in the seminar was to make peace with my past by taking in new knowledge.

Nora Volkow is a leading researcher in addictions. She grew up in Leon Trotsky’s house in Mexico City. Her great-grandfather was the exiled Russian revolutionist, who led the Red Army, broke with Vladimir Lenin and was assassinated by one of Josef Stalin’s agents in 1940. Volkow became fascinated with neuroimaging, which takes pictures of the brain.

The scholar from the National Autonomous University of Mexico made her first major contribution as a University of Texas-Houston researcher in 1985 when she traced cocaine’s euphoric path in the brain by using positon emission tomography, PET, and found addict’s brains looked like those of stroke victims.

She is a leading exponent that an addiction is not a failure of will or self-control or character. Addictions are so difficult to break because the brain is changed. Today, she heads the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which supports most of the world’s research on the health aspects of drug abuse.

She doesn’t look like a crusty bureaucrat nor like a tweedy researcher. Her body type is more like that of a ballerina who does pirouettes around old concepts with a new science.“If you want to talk about free will—that’s very interesting,” she says and combines research using brain scans with philosophy.

In fact, neuroscience is taking over as the way to understand obsessions and lots of habitual behavior— from addictions to attention deficit disorders, obesity, Alzheimer’s, and love and adolescence. The old maps leading to understanding are getting surpassed by a GPS that leaves behind the old, archaic modes of knowledge. Brain science points to not only the natural highs from dopamine (and when it goes askew) to the interaction of genetics and the environment, with implications for how life evolves from an episode to an experience.

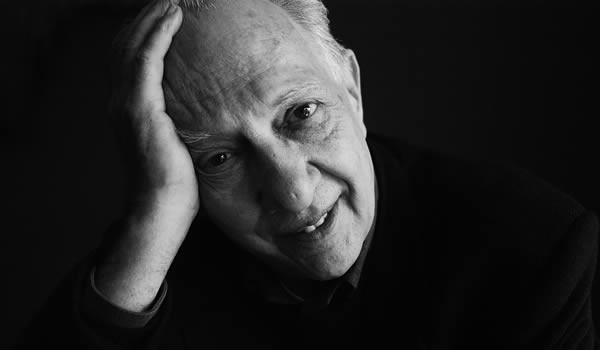

All this is instructive to artists who are often averse to the rigors of science and more adapt at the nuances and flexibility of perception. Yet, think again. George Lakoff, a linguist from the University of California, Berkeley, is leading the way using neuroscience, to show how word pictures are formed that report enlightenment and enjoyment from the brain to the mind. It is our nature as sentient beings.

It basically comes to this. Words, just like images, can evoke strong reactions and responses. This is the same dopamine pathway in the brain operating as it does with a fine coc au vin, a chocolate truffle, a nice Burgundy and making love. We are not—cannot be—easily disembodied from our words. We are by nature sensate.

Lakoff argues we become disembodied when the mind—or is it the brain—fails to associate freely and is instead harnessed into logic and syllogisms and structures where the neural inspiration leaves the thought. In other words, there is no giant equation or logic out there that will explain the world. Logic and math are just languages for translating nature. Some day, the ah-ha moment of enlightenment and understanding might get captured in a brain scan like an x-ray of philosophy.

Lakoff explained to me that about 98% of thought is not conscious. That’s why facts, unless they have “frames” around them, don’t matter. These are the worldviews going into the words we use. Our morality and politics come from what our brains are doing below the conscious level.

Furthermore, everyone has mirror neurons that fire up when you do something or see someone doing something, he explains. That’s why we can have feelings of fear, anger and happiness when we see it in others. It is how we empathize. Those neurons fire up more when we cooperate, he adds. We are biologically wired for cooperation.

Now here’s the astounding part. Lakoff says empathy has to be developed and used or the brain will atrophy. And that brave new world insight is the strongest case for the arts, creativity and the worldviews coming from writers’ words.

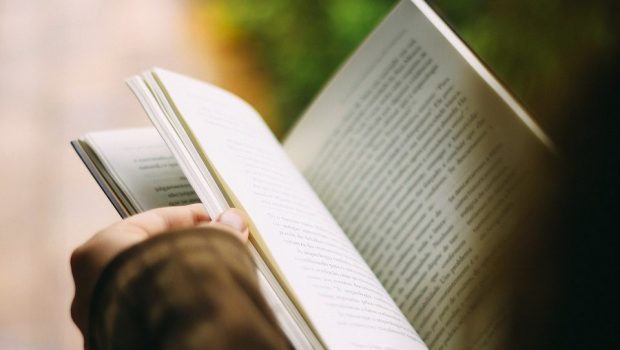

Brain science is telling us what we did not know about dialog, that it sparks dopamine and it gives readers a strange comfort and solidarity with the writer.

If anyone thinks brain science portends the end of literature as a way to understand humans, think again. Think what Persaline, Scarlett Johansen’s character, said in the movie A Love Song for Bobby Long: “Everybody knows books are better than life. That’s why there’re books.”

*José de la Isla is a nationally syndicated newspaper columnist and author of The Rise of Hispanic Political Power (2003) and the forthcoming Day Night Life Death Hope (2008)..

Posted: April 14, 2012 at 10:43 pm