The Art of Forgery

Fernando Castro

Hans van Meegeren (1889-1947) was one of the most notorious art forgers to date. His fake Vermeers even fooled experts in the Dutch Golden Age. Let us be clear: van Meegeren did not copy existing Vermeers. He intentionally painted in the style of Vermeer (and other masters) so that his works would be considered bona fide. In fact, he would never have been found out had he not confessed in order to avoid the charge of treason: for being a Nazi collaborator and selling Dutch cultural heritage to none other than Hermann Göring. This charge carried a possible death sentence. In his defense, he alleged that he was not a collaborator and that what he had sold to the Nazis were fakes of his own manufacture. Art experts summoned by the court disagreed. To prove his case, he painted a fake Vermeer while in prison. What is most telling about this case of art forgery is that if perspicacious viewers saw these forgeries today, they would find them so clumsy and gross that they would be left wondering how van Meegeren’s forgeries of Vermeer could have possibly fooled anyone, let alone experts. Indeed, the conned experts created the historical category “early Vermeers” in order to accommodate van Meegeren’s fakes.

A more recent master forger, the German painter Wolgang Fischer (b. 1951), aka Wolfgang Beltracchi, has wreaked havoc in the art world. Once again, Beltracchi did not copy existing works, but rather painted new works in the style of Max Ernst, Fernando Leger, André Derain, etc. To achieve his ends, Beltracchi scrupulously studied existing works by the target artist; indeed, he would become an expert in his oeuvre. If the information was available, he even tried to paint under the same environmental conditions the target artist did. He was so successful at producing forgeries that some of them were deemed to be the best works by a particular forged artist. Beltracchi’s forger- ies were published on the covers of catalogs from the most reputable auction houses, like Christie’s. He considers himself one of the most exhibited artists in the world, since his forgeries hang in some of the most prestigious museums.

Beltracchi and his wife Helene were arrested in Germany in Au- gust of 2010. At the time of their trial, he admitted to forging only fourteen paintings. Nevertheless, Beltracchi was sentenced to six years in prison on October of 2011, while Helene was sentenced to four years. Helene had been a key figure in the scam, providing fake provenance for the works. She alleged to be the heir of important art collections owned by her grandparents: the Knops and the Werner Jägers. She went to the extent of posing as her own grandmother, attired in the appropriate anachronistic fashion, and having herself photographed with a Brownie camera together with some of the artworks of interest. The couple then printed the picture on vintage photographic paper to make it look old enough.

The German police have identified fifty-eight paintings they suspect to have been forged by Beltracchi. Beltracchi himself claims to have forged about 300 paintings by over fifty artists. Having always been careful to use the correct materials, he would not have been caught had it not been for the mislabeling of a tube of paint that failed to list titanium as one of its components. As it turned out, white paint with titanium was not available to Max Ernst at the time he would have allegedly painted the work Beltracchi forged.

These two forgery cases have challenged the art world in various ways. First of all, they have called art expertise into question. The con- noisseurs who admitted the forged Vermeers into the corpus of his oeuvre were duped. Similarly, scores of art historians and conservators from auction houses have been obliged by Beltracchi’s forgeries to get off of their own high horses. The controversy has forced authen- tication houses and experts out of business. Legal liability issues are causing them to keep their opinions to themselves when a work that appears to be authentic is brought before them. In May 2013, art authenticator Werner Spies and gallery owner Jacques de La Béraudière were legally compelled to pay an art collector €652,883. The collector had purchased from de La Béraudière’s gallery Tremblement de terre, a fake painting by Max Ernst, after Spies had authenticated it.

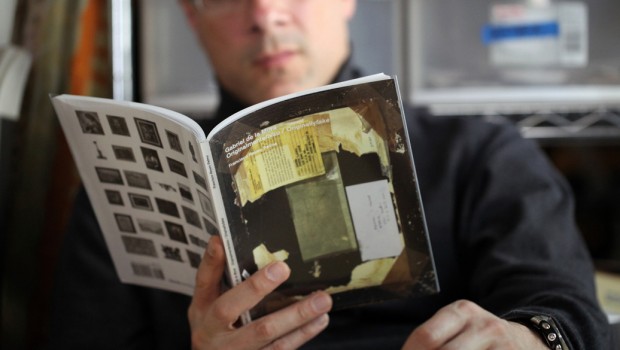

Secondly, there is the issue of aesthetic appreciation. Some of Beltracchi’s forgeries have been considered to be the best works by the artist he forged. In fact, in a CBS 60 Minutes special with Bob Simon, Beltracchi flips through the pages of a book of masterpieces of the 20th century (which I have been unable to identify) featuring one of his works. From a strictly aesthetic point of view, therefore, does it make a difference that a work is not, for example, an authentic Max Ernst, to enjoy it as such? Will our process of interpretation of the work, which usually enriches our aesthetic experience, be thwarted? The collector who had been conned with the $7 million dollar Beltrac- chi forgery La Forêt actually asked for it to be brought back to his home, because he considered it the best Max Ernst work he had ever seen and enjoyed it as such.

Thirdly, there is the effect forgeries have on the art market. Jamie Martin, one of the foremost forensic art analysts in the world, claims that 98% of the works that are brought before him for authentication are forgeries. Are collectors today so careful that they abstain from buying? Lo and behold, the voracity of the market has given a value of desirability to both van Meegeren and Beltracchi’s works. Beltracchi is currently signing his paintings with his own name; but some of his former forgeries now command a handsome price. Van Meegeren’s own have forged about 300 paintings by over fifty artists. Having always been careful to use the correct materials, he would not have been caught had it not been for the mislabeling of a tube of paint that failed to list titanium as one of its components. As it turned out, white paint with titanium was not available to Max Ernst at the time he would have allegedly painted the work Beltracchi forged.

It is worth mentioning in this four-part narrative that de La Mora had an early encounter with an accusation of plagiarism when in 2001, he painted and showed some works in homage to Robert Mapplethorpe; among them, Man in Polyester Suit. Although de La Mora’s subtly colored painting is different from Mapplethorpe’s black-and-white photograph in significant ways, the Mapplethorpe Foundation threatened the young de La Mora with legal action for violation of authorial rights. They demanded that he either destroy the works or share the profits of their sale with the foundation. De la Mora stood his ground and argued the case legally. However, the controversy took a physical and psychological toll on de la Mora from which he is still recovering. It was ironic that a foundation represent- ing an artist whose work pushed the limits of the art world in so many ways would make such an issue out of the process of appropriation, so different from plagiarism. In fact, appropriation has a long tradition in art history. There is a Picasso After Velásquez, a Lichtenstein After Picasso, and Andy Warhol appropriated the look of Campbell soup cans and Brillo boxes.

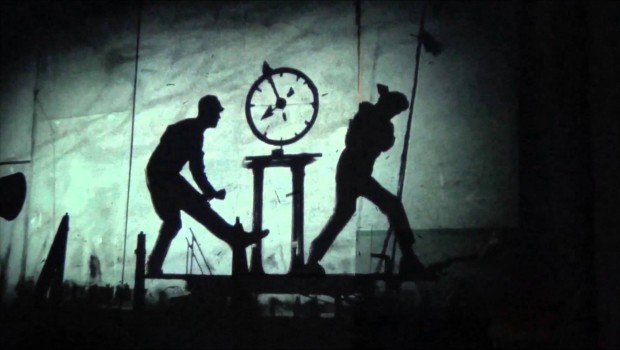

According to Mr. Reyes, a decade after the incident, de la Mora decided to burn Man in a Polyester Suit until it had been charred into a dark monochrome. According to Mr. Reyes, “This provocation and af- firmation of authorship serves as a symbolic point of departure for the project Originallyfake…” One might add that this cathartic ritual also pointed the way to what would become de la Mora’s modus operandi with regards to forgeries. For burning is exactly what he did with Cuauhtémoc, a forgery alleged to be a real David Alfaro Siqueiros work, for which the collector Lance Aaron paid the Galería Irabién in Miami $55,000 dollars. De la Mora later acquired the work from Aaron with a promise to swap it for one of his own works. Writes Reyes, “This picture of the defeated Mexica hero included a certificate from Adriana Siqueiros and was listed in the records of patrimonial inventory kept by Rafael Cruz Arvea at the National Institute of Fine Arts, until it was later discredited by the institute itself.” Had it not been for the art acumen of Aaron himself, who detected a mismatch of alleged dates, the scam would not have been discovered. De la Mora used this forgery as material to be transformed by fire in order to produce D.A.S. 2011 (acrylic on novopan, frame, fire).

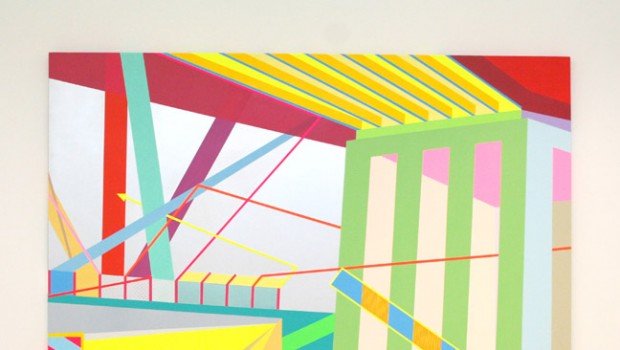

However, burning is not the only strategy de la Mora uses to do art with forgeries. According to Reyes, “he grinds, flays, dissolves, scratches, incinerates, melts, erases, encrypts, masks, blurs, empties, and corrupts, recurring to the phantom, the double, the reverse, the reflection and the filling.” For F.K. 1954 capas de pintura (2011), de la Mora used as material a forgery of a Frida Kahlo still life that he found in a flea market. This time, the artistic metamorphosis consisted of making an inventory of the palette of colors in the forged still life and then painting over the canvas and the separated frame layer upon layer of the inventoried colors. De la Mora painted 1954 layers, a number emblematic of Kahlo’s demise. The original colors of the painting remained on the back of the canvas and the edges of the new work, as if they were geological strata. Moreover, the original forgery underwent a transfiguration that changed its art form from straightforward painting to sculptural object.

Most importantly, in both of the afore-mentioned cases, the forgeries underwent not only those transformations, but a change in artistic paradigm as well. They went from forgeries through which, as José Ortega y Gasset in his unjustly forgotten classic The Dehumanization of Art (1925) described, we could see a “garden” as we would through a window pane, with differing degrees of clarity, to a way of doing art in which what matters is the pane; sometimes in and of itself, other times due to its history, its context, its previous use, etc. Many readers have taken Ortega y Gasset’s observations to be a critique of what then was yet to be named “modern art”, but arguably, he was simply being reflective and descriptive. The book Gabriel de la Mora: Originalmentefalso / Originallyfake is also a reflection and description of how one particular artist’s oeuvre evolved as a result of a confrontation with an art institution into one that unveils the often untold and uncomfortable secrets of the art world.

Posted: May 27, 2014 at 12:32 am