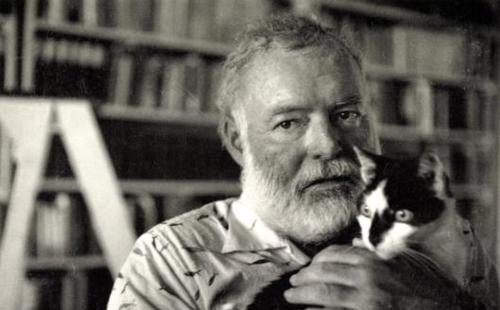

The Other Hemingway

Debra D. Andrist

René Villarreal and Raúl Villarreal,

René Villarreal and Raúl Villarreal,

Hemingway’s Cuban Son: Reflections on the Writer by His Longtime Majordomo,

The Kent State University Press,

Kent, Ohio, 2009

When Ernest Hemingway, the consummate stereotypically macho writer, bought Finca Vigía, an estate outside Havana, Cuba in 1939, he decreed several dramatic and most un-stereotypically characteristic changes in the management of the property. One such change was that the neighborhood children would be allowed to play on the property and eat the fruit grown there as long as they did not damage the trees; another was that no trees would be damaged in any way, including pruning–all to the great dismay of the cruel and exacting gardener who had worked for the previous owner!

Central to the beauty of both the main house and to Hemingway’s decree was a large picturesque ceibo tree, a type whose roots are very shallow, yet they intertwine with the roots of other trees and stabilize all. Hemingway upheld his antipruning stance even when the roots of said ceibo later began to invade and deform the floor of the house. In the meantime, Hemingway had hired several of the heretofore banned neighborhood children to run errands, among other tasks. These children also were playmates to Hemingway’s visiting children of a like age, especially in baseball games. In fact, the Cuban children were the ones to coin Hemingway’s sobriquet, Papa, because they found the name, Hemingway, difficult to pronounce and began to address him as his own children did. Hemingway’s amused friends and guests picked up the nickname from the children.

One of those children ended up serving the same purpose in Hemingway’s personal and social life in Cuba as did the tree for the Cuban property itself. René Villarreal, who began to work for Hemingway at the age of ten, became the majordomo of the writer’s estate and life in Cuba by the age of 17 and continued in that role until Hemingway’s suicide and beyond. René was the metaphorical ceibo tree for the writer himself. Forty years later and now living in the United States post-Cuban Revolution, René has dictated a memoir of his still very sharp and clear memories of that experience during Hemingway’s life in Cuba to his own youngest son, Raúl Villarreal, preserving unique insights into all aspects of the writer’s character and life.

Hemingway’s Cuban Son: Reflections on the Writer by His Longtime Majordomo is an unassuming and easy read, highlighting little-suspected contrasts in the writer’s personality and behavior. A stabilizing and organizing force throughout Hemingway’s marriages, drinking to excess, clandestine activities in the waters around Cuba during World War II and more, Villarreal doesn’t mince words in his portrayal of the writer, in spite of his obvious affection for him. Notably, he does resist focusing on the political changes in Cuba which eventually and painfully drove him from his all-consuming dedication to Hemingway and the writer’s legacy in Cuba. He never resorts to diatribe, but chronicles those changes as, and only as, background to the greater saga of the contrasts within Hemingway according to Villarreal.

As Hemingway’s decrees about children and trees suggest, this man’s man, the safari hunter with the mounted animal-head trophies to prove his prowess with the gun, the cockfight and bullfight aficionado, the sports enthusiast so devoted to boxing that he taught René well enough that the latter was a contender in Cuba, had a dramatically different side. Hemingway released caged birds, adored and coddled cats and dogs, among other practices seemingly contradictory to his public persona. The extent of this softer, more humane, side might never have been widely known without Villarreal’s memoir.

Posted: April 21, 2012 at 11:17 pm