La marca

Michael McGuire

Every terrain has its secret.

Every forlorn family circus this high in el cerro knows the secret of a slanted, odd shaped lot in Pueblo Nuevo. How to set the tent, the stands, so the unevenness of el terreno is not noticeable.

The unfed mare, too, has un secreto. Here is one place in Pueblo Nuevo there is no door to chase her from, where the hard scrabble belongs to none, where she can scavenge between empty postholes and the ditching that circles the tent that was there not that long ago. Tonight her knowledge is useless. Other stakes have been driven, another tent pitched. Tonight the mare must also wander.

*

Three sisters.

Each divided from each by a year and a half, an indistinct face of a distinct father, not one of which any one of them would know if it were suddenly bent to hers…and slowly turned away.

Sisters who share a mother. A mother who does, in her way, provide. A mother who reads without effort.

One sister, eldest: cheeks of a clown, behind tight as a boxer’s; walk of an angry man, fists clenched. The second: shapeless as flowers, a month between seasons; business head, willing to negotiate. The third: bony, straight haired, determined; if there were Apache blood in Pueblo Nuevo, she would have her drop.

Each of three divided from two by a year at la preparatoria. None without difficulty reading, all confusing m’s & n’s, b’s & d’s, p’s & q’s; shuffling letters and numbers, confounding words. Three who, nevertheless, have been known to speak smoothly, at once and, sometimes, all together.

Seasonless summer, shimmering fall. Day white as egrets, as herons; sharp enough to carve the eye. Sun still stark, if angling. Not quite horizontal.

Sisters flanking each other. One cobblestoned direction, another, at the end of which lies…

La celebración. Celebration of Paloma. Su cumpleaños.

After which sisters shall offer their offering: a day out for the birthday girl who, like the sisters, must have heard the sound truck sound. And may even herself have made sense of a pronouncement loud and clear. An old man’s voice, a father’s, augmented by technology, booming between walls, ringing the sky over Pueblo Nuevo:

¡..una noche..!

¡..la primera y última noche..!

¡..ven! ¡venga..!

¡..ve..! ¡..vea..! ¡..el león salvaje..!

…y…

¡.. la contorsionista más pequeña del mundo..!

*

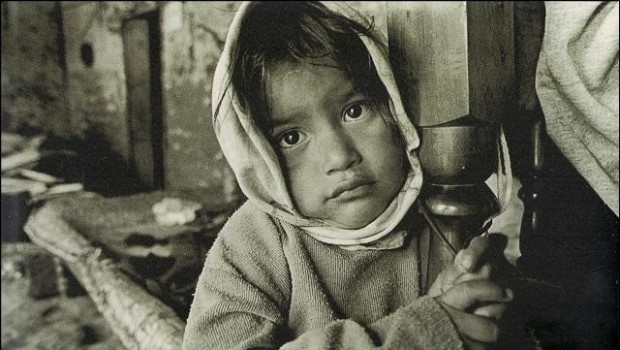

Paloma.

White as a white bird. Excepting an imperfection to shadow one side of her face. Site where a touch of damnation seems to have entered, taking, apparently at once, language, intelligence, growth, control over her own never-to-be-developed body, womanhood. Not taking life, a delicate femininity, perception, a kind of grace.

Touch of an unseen, unimaginable hand, one that disfigures at birth, defaces. The outward sign.

La marca

de nacimiento,

una marca not without form: bird, butterfly;

some perceive the dark shape de la Virgen

distinguished on rocks, walls, billboards: Guadalupe

the graceful, giver of the gift

of forgiveness,

healer.

Or was it only the mariposa lily, the mariposa orchid, that settled on Paloma’s cheek never to rise? Leaving only some notion of nature, a caprice, una curiosidad where Paloma ought to have been.

Paloma, pale enough to mount when only white was allowed to, una dama de Nueva España; mixed blood of her parents to cloud one region only; Paloma, unable to sit a horse, even when held, Paloma, strapped in, entertains from a wheeled throne, una silla con ruedas.

Paloma’s twentieth birthday. Su cumpleaños. Her body would tell you she is no more than twelve.

Paloma’s hands, at rest, graceful as grace, more perfect than perfection, hands that will never know work.

Paloma loves bright colors; Paloma never looks up; Paloma loves to run white lace over the backs of her hands. Her aspect softens; her narrow, classic face shines. The mark that darkens one side darkens further. What does she see in this colorless cloth, this fabric made by looping, twisting, knotting?

Shapes? Forms? Insectos lepidópteros of indescribable elegance, undulation; clearly capable of flight?

Paloma tied in her chair in the oblique and deferential light of the veranda, charitably softening. Paloma, who doesn’t speak at all.

Paloma who, if she reads, reads lace and butterfly wings, reads shadowed branches moving by moonlight.

*

Three sisters, each younger than she, coming to felicitate the image of a lady in white, even if nothing lasts. Youth, nor innocence nor chance. Adoration. Perfection. Imperfection. A season between seasons. Birthdays.

A short-lived luminosity between day and night in which diólogos, conversaciones, flutter about Paloma and, sometimes, land.

¡Hola! Paloma.

¿Cómo estás? Paloma.

Have you opened your presents, Paloma?

La graduación hoy. En la plaza. The mayor handing out diplomas.

He had to go. She took his place.

A dream, isn’t it? Me handing out diplomas! Easy. I knew everybody’s name.

Nobody refused his diploma just because it was from her.

Maybe she’ll give you one, Paloma.

Be quiet!

¡Un diploma por Paloma!

They couldn’t do that. Every diploma has a picture stapled.

Así es.

That’s the way it is.

Pos, Paloma. We’re going to gobble. What can we bring you? ¿Rosetas? ¿Rositas? ¿Palomitas? ¿Palomitas de maíz?

Palomitas por Paloma.

…popcorn, popcorn…

¡Cállate!

¿Squirt? Paloma. ¿Seven?

¡Cierra el pico! little sister. You know she doesn’t understand.

*

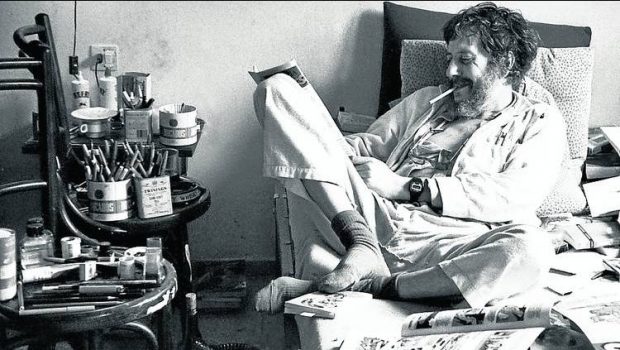

As heavens dispirit, dishearten, day in, day out, El Circo Familiar wrings a wrung circuit, flings a wider net.

It may, may not, be due to returning rain, but when El Circo limps into Pueblo Nuevo, faces fall. There are few greetings, fewer replies. If statistics were kept on contratiempos, they might reveal unaccustomed desacuerdos domésticos. As well as public squabbles. Not true throughout the changeable months, so frequently enveloped, indistinct then… Harsh. Glaring. Not true when other circuses pitch desperate tents in Pueblo Nuevo, but this is…

El Circo Familiar.

One short loop of circus polyphony feeds the loudspeaker: marching jingles one after the other, and…

The voice of el presentador father, who is, as he may soon reveal, also el bufón father in changing clownery, el ilusionista father, complete with hat trick and white dove. El electricista father also knows his wires, how to tap the pueblo’s, blind his sitting ducks, plunge his pigeons into obscurity.

El público. The children. The men who never grew up.

Squealing. Delighted. A darkness charged with possibility.

El padre del circo finds himself a tough act to follow, would have his prized apparel refurbish his reappearance, conceal la pobreza of a one-family venture, an absolute lack (with one exception) of assets. The clown father has a llama led on while he worships his wardrobe, recasts himself, a proud llama who stares over the heads of the many, takes the measure of the mountains.

And the public of Pueblo Nuevo? The patient women, their ducklings? The pesos that may be. Under pitchers, pots, pillows.

Where are they?

The sound truck, careful as the mare, is at home on the slanted, odd shaped lot. Unfinished houses, overgrown yards, do not complain of the short loop, the endless pitch. In last-ditch despair at a silent, drooping tent, at vacant stands, la camioneta attempts a rough circuit of the pueblo. No animal march, no rehearsed roar of loyal lion. Just the unproductive promotional, the unpromising push. A melancholy voice, himself, el presentador father in clown face, at the wheel. The irresistible offer:

¡Dos por uno! ¡Dos por uno!

¡Cupones! ¡Cupones!

But word is out. Some catch. At six they tell you no performance till eight. At eight they tell you cupones were for six. At the trailer window it’s uno por uno. Cupones are not honored.

*

¡Mira, señora, we have cupones!

We thought Paloma might enjoy el circo.

They say there’s a lion..!

¡..un león..!

… and a…

…a…

¡..a contortionist..!

Paloma’s mother has sad eyes, darker than her daughter’s. Paloma’s mother seldom speaks.

She has a sweet gravelly voice from the bottom of the stream, the voice of a smoker who never smoked, a voice that slides softly beneath all others. As of this night she has given twenty years to fostering, nurturing; to reading, quietly, the unreadable to the unread; to a text always warm to her touch: el apocalíptico.

Paloma’s mother can hardly imagine an hour free of foreboding, of a daughter’s ever-present, if partially deferred, doom. But she consents.

Muy bien.

You’ll be careful on the sidewalks?

If she gets excited or upset, you’ll bring her home.

Wait.

I’ll take her to the bathroom.

*

The public fails to arrive for the first representación. For the eight some drag themselves in at nine. 9:30. But at last…

Darkness.

The father of it all, the man behind the squeals, the jester, mans his switches. The hum, the buzz…

The light.

A circus of siblings.

La hermana professional with hoops keeps dozens going: neck, hips, calves: mating left, right, backwards. The pantomime hermana wears costumes the clown father doesn’t. At times she’s an overgrown tele-animalito, tumbled from the bright screen that rendered the roadshow obsolete. At times she’s death dancing with children. Death dances with el hermano too, little brother, after a playfully perilous game of chance. A misstep, a toss lost and big sister waltzes him into darkness with every hope of reprise.

And yet…

One sibling, youngest, smallest, practically a miniature, excels all others.

It isn’t easy to be the one real asset of a one-family circus. To stand straight beneath the burden. A proud llama, a toothless, even a make-believe, lion, might be permitted to disappoint. La hermanita isn’t.

Beyond smiles, she enters the one ring an hour past the bedtime that would be hers if the life she lived were hers.

The smallest contortionist in the world enters unannounced, disguised.

Boxed.

Nearly new, a shopworn hand-me-down, in a box older still; castoff, a discarded doll, a present to the penniless.

A naive public without expectations: pigeons haven’t seen her, sitting ducks do not know she lives. Men and children gape and giggle; women wait.

Brother, el hermano, unpacks the masked, the costumed doll, reveals not a centimeter of flesh, not a milligram of life. Set in a different position, she stays that way. Gravity only claims her when el hermano turns his back. Only a curious delay hints she is not some plaything in timeworn costume: used, second hand, picked from a dump where those still poorer poke and pick.

Suddenly…

El electricista father touches a switch. Darkness. The hum, the buzz…

Light.

Men and children gasp. Even women open their mouths. The discarded doll, the plaything, inhales, exhales. She yawns, stretches , makes moves the living envy.

Animated, aware, exultant, made in no image other than her own, a flexible vertebrate stands upright. She walks the earth.

Un fuerte aplauso.

The doll, the discard, the gift, the gifted, has brought the house down.

A bow few could make. A timely darkness to reap the ovation. Perhaps a loyal, if tattered, lion will not be called upon. Maybe word-of-mouth…

Next day el presentador father in cautious soundtruck and painted grin, will, once more, announce la ultima noche. Next night will see el espectáculo restaged with minor variations, the guaranteed discount ever deeper, more doubtful…

*

Until the night three sisters bearing coupons pay the pesos first asked of smaller children and the smallest contortionist in the world appears.

As herself.

La miniatura enters in flesh tight sequined satins, purple, gold, a worn outfit to allow unbelievable contortion, that clearly reveals the infantine body, the featureless nonage that permits such suppleness, sanctions such divine deformation.

Three sisters enter opposite, wheeling an ungainly throne through mud, through sawdust, take their places, planked side by side, framing their guest.

The eyes of el bufón father eye one sister, the eldest.

La miniatura in satin may not be able to see beyond the light in which el electricista father, still in his clownery, bathes his discount customers.

Sisters can.

*

¡Mira! She’s doing it for her.

¡Mira! Paloma.

Are you looking, Paloma?

Look!

She’s doing it for you.

One sister whispers in Paloma’s ear. Another touches her arm. Paloma runs her lace over the backs of her hands, angles her classic head, widens her gaze. The shadowed side of her face, la marca, caught in circus dazzle, glares black, black-red, bloodred. Shade, minus the gold, of the threadbare costume of…

¡La contortionista más pequeña del mundo!

La niña drops her shoulders, thrusts her breastbone, bends backward, lowers her head to a cloth on the table, stands straight upside down. A stick, a toothpick. A six year old. La niña presses flat upon her breast, twists impossibly to face three sisters, Paloma of the wheeled throne, all for whom los cupones somehow, finally, worked.

La niña draws legs from behind up and over, lowers fine ankles, firm and professional, untrembling, to flank a child’s face. Face of a child philosopher, baldly lit, ageless; mystery of adaptation, necessity, made visible in a smile that’s not a smile; perspiration that is not perspiration.

What does a wheeled young woman, washed in an electrician’s blaze and white as una dama de Nueva España, see? Beyond the fragile warp of a girl’s bird breast, her stretched midriff? Beyond the bend, the twist begged of time and achieved with endless labor?

Paloma’s eyes rise from her scrap of lace, fix the oddity contrived before her.

Three sisters wonder if Paloma is aware of eyes sited in a face younger than her own, eyes now used to lights. Eyes on her eyes. Does a half smile waver between gifted, if overworked…and blasted, if undestroyed? A flicker of conmiseración between the yet to bloom…and the never to bloom? The former, a curiosity made curious, even to Paloma, perhaps, by fine feet, performer’s feet, placed each side of a child’s fine face; by proof of pubescence, so clearly outlined in muted rose with gold filigree and–so improbably–overhead.

What on earth..?

Some anomaly, some minor miscreation suited only to the sideshow, the tent, the tour, or…

A monstrosity? A freak?

Another?

If there is one more, how many are there? And where does it stop in this, the ordered, the boundless and interminable, the everlasting and incurable…

Cosmos?

Paloma feels her features contort; her eyes tense, tighten; the blotch, the blemish, throb upon her cheek. A useless tongue arcs in her mouth. Paloma herself would touch, transform, make right. Hands rise, but…

Hands move only backward, hands lovely as loveliness, white hands, trailing only the unspoken, as bodily form bent only to bearing the unbearable and strapped against self-destruction, bends and bows. And the device the divine itself must have thrown a wrench in whines unheard.

A loop of polyphony scratches to silence, the voice of el presentador father requests, demands, un fuerte aplauso which a public which was, in the past few minutes, itself very nearly some departure from the natural, the human, denies. Men, women, couponed children who howled at darkness not that long ago, struck silent, watch a young woman twisted in her chair…and a contorted child eye each other.

In silence rises a soundless sound none, yet all, can hear…

Quick!

Get her out of here.

She’ll panic the lion.

I think the clown’s coming to get us.

Quick!

Have three sisters moved as one? The middle leaping from the stands to turn la silla con ruedas, the largest to press on through sawdust ever deeper, the smallest to retrieve Paloma’s fallen lace?

Appalled sisters wheel a wheeled throne deeper into sawdust, urine, fleas. Silence only shrieks the louder. Paloma’s hands, arms, uncontrolled, embrace, not the undeserved suffering of this world, but an armful of air, another, beyond her own never-to-develop bust. La silla con ruedas sinks to a halt. If she were not strapped, Paloma would be thrown, flat and twisting, before eyes she alone sees, or thinks she sees, eyes that must see and sanction all.

The sisters’ final effort: three pushing as they sometimes talk. At once.

La paloma is gone, impelled into the night by those who brought her. La miniatura, upside down, faces a gaping, unfilled ring; a waste of sawdust.

The smallest contortionist in the world raises faultless feet from the oval of her face with trembling slowness, attains once more, upon her head, the perfect vertical, as if the improbable exit, just witnessed, and so much more, if not quite all, must make sense from that position.

El presentador father, forever the funnyman, as ever to the rescue, restores the loop to its polyphony, holds el micrófono close as a rock star, roars the incredible arrival of the incredible lion. Children, men who are also children, remember his demand for vigorous applause. Teeth glisten. Eyes shine. Hands smack.

The audience is itself again.

Offstage, an unlikely sovereign, toothless, fleabitten, hurries an unlikely entrance.

*

Calavera, Pueblo Nuevo’s death’s head mare, wanders the pueblo, at times stoned by children, most of the time ignored. In this season there is roadside grass. Grass goes down easily. Calavera drinks as she eats, eats as she drinks. Calavera is on her own and knows it.

La yegua has an owner who knows no temptation to restrain, retrieve, roof or nourish, and claims illness has resulted in the mare’s disconsolate wandering. But it was hunger taught Calavera to open gates. After she’d eaten the bark from the posts that held the fence that held her, there was lift the loop of barbed wire, step ladylike through fallen strands or…

Half starved anyway, Calavera’s hip bones spread behind her. Wings of a butterfly. Shoulders of a beekeeper, an office drudge. A ridge rides between hips and shoulders: a back to carry no man. Not even a rider as weightless, as bare boned as she. As delighted in the harvest.

La yegua can see well enough, in spite of the cloudiness that blurs whichever eye she eyes you with. If you pass, due to some peculiarity of vision, she does not follow, but walks abreast. For reasons of her own she has chosen you. Half a block. More. Until the tuft, the growth that shouldn’t be ignored makes its appearance, left or right.

For that half block, Calavera will consider la posibilidad she has a patrón after all. She will be fed, watered, roofed. Not as any animal places claims upon the animal claiming dominance.

More.

Calavera walks peacefully. She has seen. There is a plan. There must be. The scant times are so she should appreciate the free. She knows, but that is not the secret of this terrain.

Calavera seems capable of great speed. Never to be ridden, she has the stretched body of the horse who carries the stretched rider, forever at the lean, the ready. The gallop.

Into the yield that knows no limit.

That is the secret.

*

Who can relate how Paloma was wheeled on broken footways, eyes open, mouth wide, arms embracing the enormity from which she would not shrink? How sisters took Paloma home? How she looked when she got there?

We’re sorry.

Really sorry.

She loved the hoop girl. She laughed at la contortionista.

I think she laughed. She clapped.

Really clapped! Her hands came together.

She was having a good time!

The lion upset her.

The clown scared her.

It must have been the blackouts.

Or the light.

*

La dama de Nueva España, home at last, mouth open, even now, in a lament only crowds and animals can hear.

Her mother, specialist in composure, expert in stilling soundless sound, in reminding her daughter as she sometimes needs to be reminded, offers an ornate and gilded instrument, a mechanism of self-appraisal, self-knowledge. Paloma, no longer embracing the world she held from one end of Pueblo Nuevo to the other, allows arms to be uncurled, fingers to be placed.

Gripped.

Three sisters, a mother, gone, a handheld mirror trembles in the light from the hall.

Paloma, alone with her resemblance, remembers what remembrance can.

Paloma, her eyes saying all that need be said, has answered her own question. A family circles the circus hell when a deeper, darker circuit waits.

Noting empty stands left and right, Paloma had asked herself, why…

Why, when even one salary would equal performance, minus days on the road, gasoline, faded rose and golden filigree for la contortionista, butcher’s waste for the lion, weeds for the llama, countless changes for the clever father of it all, does la familia persist?

Or, to put it as her mother must have, certainly did, standing behind her chair, leaning, whispering in the soft rough voice of a smoker who never smoked: what has each and every one of us done in the days that preceded?

How many clumsy missteps must be written in the face we face our lives with?

Paloma, alone with her self-same twin, her look-alike, with white fingers that shrink from contact with so white a face, watches la marca flush, flutter, land and raise deceptive wings, watches the scene before her peopled and unpeopled.

Reanimated, the image of el padre del circo tosses a fluttering dove from his handkerchief. The quick eyes of el ilusionista father count the house, note late arrivals, weigh the success or lack thereof of every sleight of hand. There is no pleasure, not even guilty pleasure. Only the talent, managerial at best, of el presentador father, forever at work. Has, Paloma wonders, el electricista father, jester of the dials, the switches, been made to fry in the hellfire of his own electricity?

Or is it worse? Paloma knows how the unseen is often worse than the seen. Where is the mother in that family of five or six? Are they, minus the son, daughters got on daughters? Are quick clown eyes behind it all?

The family, dragging the chains of necessity, follows in his footsteps.

But what has la contortionista done to deserve the smell of unburnt gas, the lice, the ticks, the lump in the throat before the empty house, the knot in the stomach that never goes away?

Paloma, trembling mirror in hand, la marca throbbing with a thousand scenes, counts, recounts, observes, among others…the hoopgirl sister mating left and right; el hermanito awhirl in the waltz of time and already paired with death; the llama overlooking mountains no one else can see; the roaring king of beasts painfully aware of his own need of dental work…and arrives once more at…

La contortionista más pequeña del mundo.

Body of a question mark, a parenthesis, suppleness to match a father’s slipperiness, an exclamation mark bearing the burden of word-of-mouth that swells the house an unlikely second night and, si Dios quiere, packs them in a barely believable third.

The fifth or sixth family member of the family, age six. What has she done besides her duty? She must have bent to acrobatics from the womb. Twisted to her training. Never deceived or cheated. No time to lie. She has yet to break a heart. Who could recount her child size sins? Who, what, could rejoice, or even breathe relief, at such everlasting effort, such devotion?

Paloma, in her own past, parked close, too close, to the bright screen to still her soundless sound, has seen the other circus. She knows. There is more than flood and drought. Earthquake and hurricane.

More.

Paloma, herself the creature who was not drowned at birth and still alive in a everlasting present, watches a white face whiten, an exhausted butterfly blush and pulse. A white hand soar free of its eternal lace, mounting white as doves in the dead white over el campo santo, watches the back of a perfect hand touch perfect teeth and wishes she could give them to the king of beasts.

Paloma looks and sees.

She reads.

The grimace of extinction beneath a lively father’s funny face. A stiff spine-damaged woman once lifeblood of a failing family circus. A boy no longer a boy plying a trade in Tijuana better suited to boys. A girl no longer a girl who has found a more rewarding use for her gyrations than keeping hoops in motion.

Or is it worse, the world to come? Much worse. Will the old man behind the makeup, priceless apparel drenched and dripping, swim the cesspits of eternity? Climb its dunghills? Do the cesspits boil? Or freeze?

This life, she concludes, must be delight, thrill and satisfaction, to those who designed the afterlife and, in this one, did not forget that here, here and now, something beside the body might twist and writhe, contort itself a thousand times, before the strapped and seated prison it knows so well offers release.

And still she hears her mother’s voice. Sweet, gravelly. A voice that slides softly beneath all others.

Think back, Paloma, remember.

If you try, we try, we remember our past lives.

Down deep we know what we did.

What we did to warrant what happens to us in this.

This life.

Who, what, we are.

We know.

Posted: August 14, 2013 at 9:55 pm