This Machine Kills Tweets

José Antonio Simón

Alighiero Boetti´s PDF

Many a thinker has denounced the dangers of thinking in 140 characters, mostly relating it to productivity and concentration in the work place. I am adding this idea and my concerns to the realm of visual arts. The reason is that modern/non-representational art has always faced the challenge of convincing newcomers, or lay people, of its legitimate purpose. Modern artists seem to be walking in the footsteps of the old philosophers, and yet, it seems they are still perceived as esoteric or elitist because no one thinks to understand them. One often sees people in museums looking from the painting to the author’s label, back to the painting, as if searching for that one thought or tweet that will unlock the meaning behind the work.

It’s not there.

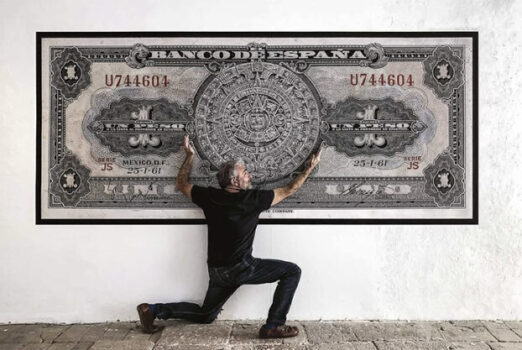

Why? Because if things do not have a cost, they can never have value. It is the job of the philosophizing artist to impregnate their work with ideas and meaning rather than to write them down on paper. This seems so at odds with the current state of the world in which it is thought that, not only must access to information be easy, but it should be instantaneous. Enter Alighiero Boetti; or better yet, Alighiero and Boetti. As one of the most important figures of the Arte Povera movement, Boetti is well versed in enriching mundane objects with ripe ideas. His art is the perfect example of this point, as it is the ultimate expression of art as a medium for ideas and perspective in its lacking of technical achievement or craftsmanship. The artist’s work is especially compelling when his several periods are displayed together, as the several stages of his work keep in the same pattern each individual piece to conveys: the duality of things. That the world manifests two, opposing forces is an idea that is quite old, but what truly resonates about his oeuvre is that the art, like many of its contemporaries, requires analysis and comparison. These are the tools that society is built on; it is how we can discern patterns, and thus meaning.

A joint venture with London’s Tate Modern, Madrid’s Reina Sofia a retrospective of Boetti’s works is currently displayed in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition celebrates the material diversity, conceptual complexity, and visual beauty of Boetti’s work, bringing together his ideas about order and disorder, non-invention, and the way in which the work addresses the whole world, travel, and time, proving him to be one of the most important and influential international artists of his generation.

A brief moment of continual thought opens worlds for the viewer. Compare, for example, two works: the first is Rosso Gilera 60 1232/ Rosso Guzzi 60 1305, created in 1967, and the second is 16 Dicembre 2040–11 Luglio 2023 (December 16, 2040–July 11, 2023), woven in Kabul, Afghanistan, in the year 1971. Visually one can discern a clear pattern; both consist of two panels, placed side by side that display information. The first work has the name of the two shades of industrial red used by legendary motorcycle companies of Italy with which

the panels are coated, the second shows the 100th anniversary of his birth alongside the predicted date of his death. Both can be called portraiture, both can be deceptively simple and both are a finger that point to different directions. These works signal the viewer to look at the role of industry in how we experience the world and to ponder life and death; both significant topics presented in a seemingly beautiful medium that wouldn’t suggest the messages they are pregnant with.

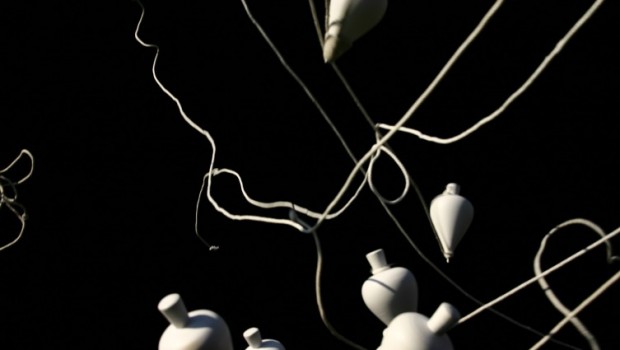

Without wood, glass and an electrical device, the work Ping Pong, (1966), couldn’t exist, nor could the ping without the pong, nor could the art without the observer, nor perspective without thought, nor the idea without a mind.

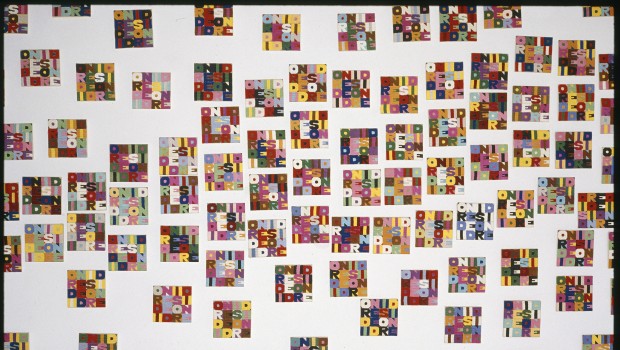

As the MoMA itself put it “The exhibition brings together these and other works related to travel, geography, and mapping, many of which relate to his extensive travels to Afghanistan, where he operated the One Hotel from 1971 until the Soviet invasion in 1979. During this period, Boetti began working with local artisans to produce embroideries such as the Mappas (maps), Arazzi (word squares), and Tuttos (literally, “Everything”).

*Iimage by Alighiero Boetti. Courtesy of MoMa

Posted: September 21, 2012 at 3:53 am