An English Voice for Ribeyro

Jorge Iglesias

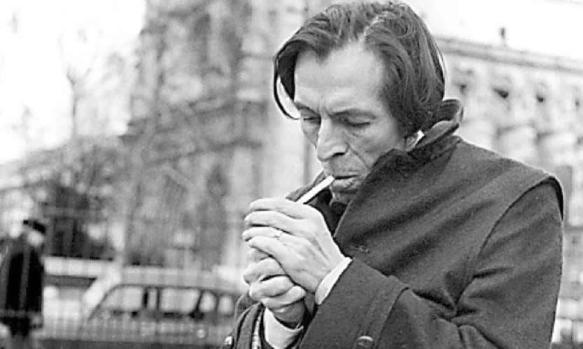

Julio Ramón Ribeyro,

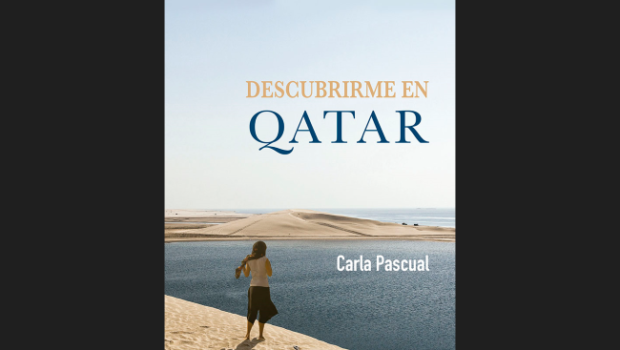

The Word of the Speechless,

New York Review Books,

New York, 2019

Trans., Katherine Silver

When discussing the mid-twentieth-century Latin American short story, it is inevitable to invoke the names of Gabriel García Márquez, Juan Rulfo, Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, and Mario Benedetti, all of them authors that the English-speaking public has been enjoying for decades. The name of Julio Ramón Ribeyro may not ring a bell in many North American ears, and yet this Peruvian master of the short story, a contemporary of the authors mentioned above, stretched the boundaries of the genre by giving voice to the voiceless and questioning the formulas that pushed traditional narrative along the beaten path. The present collection of nineteen short stories introduces English readers to one of the most unfairly neglected figures of Latin American letters.

Written throughout a period of forty years, the stories contained in The Word of the Speechless illustrate the thematic amplitude of Ribeyro’s output. From the fantastic to the quotidian, these tales feature an array of characters that are both local and universal. García Márquez and Rulfo were drawn to a certain type of setting or character; Borges and Cortázar, to a certain type of theme or mode. Ribeyro’s trademark is above all a personal, inimitable way of looking at reality: he tackles a wide range of subjects with equal grace and charms the reader with his unique perspective. Some of his stories are reminiscent of the Cortázar of Bestiario (1951), while others bring to mind the Benedetti of Montevideanos (1960), but just when we think we have stumbled into familiar territory, Ribeyro surprises us with an unexpected turn. The narrator, for instance, may choose to omit the ending of a story altogether, thus letting us know that the ending is not the point. Or he concludes a text to go buy a pack of cigarettes, and we understand, because few storytellers are as generous and amiable as Ribeyro.

A back-to-back reading of the first and the last story in the collection suffices to demonstrate the variety of Ribeyro’s spectrum. In “Tracks,” a man finds bloodstains and decides to follow the trail. Like Cortázar’s “Continuity of Parks,” this “short short” is a paradigm of narrative economy, and may be read as a doppelgänger story or as a parable that suggests that the suffering of others is also our own suffering. Closing the collection, “Music, Maestro Berenson, and Yours Truly” follows a young lover of classical music as he meets a European maestro who went to Peru escaping the horrors of World War II. It is a coming of age story that measures the abyss that separates ideals from reality.

Ribeyro belongs, at least in one of his facets, to Kafka’s lineage. This is evident in those stories that depict guilt, shame, or fear. In “Out at Sea” it is not the plot that matters but the mood or the state of mind. Feeling guilty about the way he has treated an acquaintance, the protagonist is convinced that the other man will take revenge. The result is a response to Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado” that presents the other side of the coin. Poe’s tale had no beginning and focused on the man taking revenge; Ribeyro’s has no ending and focuses on the man racked with guilt. Shame is the subject of “Meeting of Creditors,” “The Substitute Teacher,” and “A Nocturnal Adventure.” In the first story, a grocer struggles to maintain his dignity after being humiliated by his creditors and his son. “The Substitute Teacher” is a nightmare that takes the reader from elation and enthusiasm to the starkest despair. One of the most effective stories in the anthology, “A Nocturnal Adventure” has as its protagonist a loner who one night sees a woman smiling at him from inside a café. An apparent dream come true is dashed to the ground. Like Kafka, Ribeyro knows well the territory of broken dreams. “Barbara,” a story of frustrated desire, also takes place in this setting. It concerns a couple divided by the language barrier. The protagonist is sure that he is making progress with Barbara; nothing could prepare him for the bizarre climax of their relationship.

Solitude is another salient theme. It may be felt in “The First Snowfall,” a tale about codependency in which an eccentric poet invades a man’s home. It is a sad truth that some people will prefer humiliation to loneliness. Another story that revolves around a lonely figure is “Silvio in El Rosedal,” one of the longest featured in The Word of the Speechless. As Silvio reluctantly manages the hacienda he has inherited, he becomes convinced that the roses in his garden spell a word in Morse code. Is he reading too much into things? Are we? An ominous fate hangs over this story, the sense of the inevitable that one may find in Poe’s “Metzengerstein.”

From among the stories in a fantastic vein, “Doubled” stands out. It may seem that by 1955, when the story was written, the doppelgänger theme had been exhausted, but Ribeyro gives it an interesting, ironic spin based on the premise that “doubles always tend to carry out the contrary movement.” Another memorable fantasy, “The Insignia” follows a man who finds a mysterious emblem and decides to wear it, with hilarious and terrifying consequences. In “Ridder and the Paperweight,” a limeño finds, in Belgium, a paperweight he threw out of a window in the Peruvian capital. “Nothing to Be Done, Monsieur Baruch,” in which Ribeyro himself makes a brief cameo appearance, relates the last moments in the life of a man who committed suicide, from his perspective. Finally, “Nuit caprense cirius illuminata,” a kind of ghost story, describes the reunion of two old lovers. In this ambiguous tale, the beloved may not exist or she may be two women simultaneously.

Two stories in the collection may be viewed through the lens of what we now call creative nonfiction. “The Wardrobe, Old Folks, and Death” revolves around an immense wardrobe, a family heirloom, that is the pride of the narrator’s father. In “For Smokers Only,” the author explains the role that cigarettes have played in his life and literary career. These texts, especially the second one, are refreshing, as the reader feels invited into the author’s personal life.

Ribeyro also enjoys writing about writers: “A Literary Tea Party” and “The Solution” attest to it. The former is a light farce in which a group of snobs prepare for a meeting with an author. In “The Solution,” which may also be read as a humorous piece, a writer describes the story he is writing, about a man who suspects his wife of infidelity and plots revenge. Like Cortázar, Ribeyro understood that great literature has much to gain by not taking itself seriously.

“At the Foot of the Cliff” deserves a separate paragraph. In this magnificent tale, a man and his two sons live at the beach, where they build a house and make a precarious living through hard work and ingenuity. The protagonist faces loss and the antagonism of authority. The poor, the narrator says, are like the higuerilla, which grows even in the least propitious places. “Wherever a man from the coast finds a higuerilla, that’s where he builds his house, because he knows that he, too, will be able to live there.” A testimony to the stoicism and resilience of the least fortunate, “At the Foot of the Cliff” shows Ribeyro at his most compassionate, humanistic, heartbreaking, and hopeful.

With The Word of the Speechless, Katherine Silver—whose translations include Martín Adán’s The Cardboard House, César Aira’s The Literary Conference, and, more recently, Juan Carlos Onetti’s Collected Stories—introduces the English reader to a spellbinding Latin American narrator. This is a translation worthy of Ribeyro, and one that cannot fail to spark readers’ interest in other authors from the region. Some authors—Cortázar and Lispector are the first names that come to mind—are a pleasure to discover. Nothing equals the exhilaration of that first meeting. Ribeyro is one of these authors, and those of us who know him can only envy those who are about to discover him.

Jorge Iglesias has a Ph.D. in Hispanic Studies from the University of Houston. He has received the Emma López Award for Excellence in Teaching (2013). He is a contributor to Literal Magazine.

Jorge Iglesias has a Ph.D. in Hispanic Studies from the University of Houston. He has received the Emma López Award for Excellence in Teaching (2013). He is a contributor to Literal Magazine.

© Literal Publishing.

Posted: November 19, 2020 at 8:45 pm

I absolutely love Ribeyro´s work. Great to remember him.