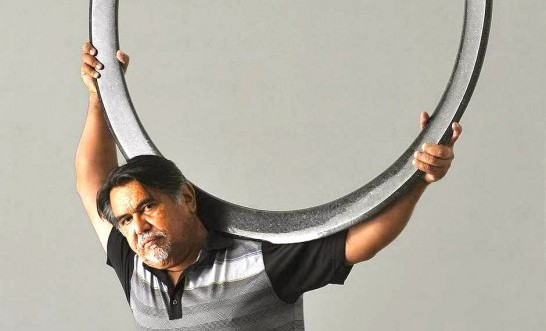

Jesus Moroles, Sculptor (1950-2015)

Fernando Castro

At age sixteen, when most kids are playing ball games, Jesus Moroles was running a prosperous silkscreen business. The Vietnam War interrupted these early artistic endeavors when he was drafted into the Air Force. Unlike many of his high school friends who died in the war, Jesus did not have to face combat duty because of his mathematical and technical skills. The Air Force considered his repairing electronic equipment at bases in Nebraska, Mississippi, and Thailand more useful to the war effort than shooting at Viet Cong guerrillas. After he was discharged from the military, Jesus studied sculpture and engineering at El Centro Community College in Dallas, and later at North Texas State University in Denton, where he first sculpted limestone, marble and granite. Moroles remembered the first time he engaged granite: “I was holding a hammer with both hands, I had on earplugs, goggles, a dust mask, a scarf around my neck and a hardhat. The overalls I had over my own clothes were covered with a cake of dust. I couldn’t hear or see anything (…). When I stopped, I realized there were about thirty people around me watching what I was doing. The stone took over. It was so hard it barely showed what I had done to it. I had not even scratched it! But it controlled me. I fell in love with it.”

Black Spiral Disc, 2012

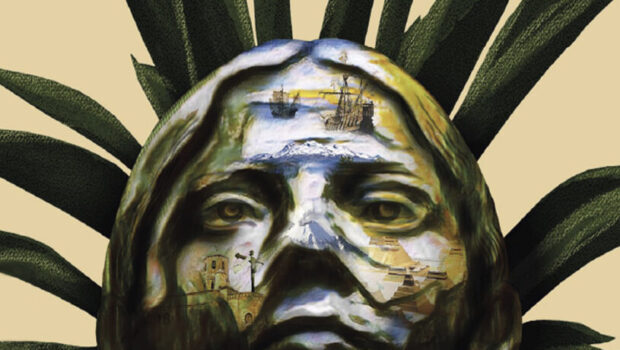

After graduating from North Texas State University, the renowned sculptor Luis Jimenez took Moroles under his tutelage for a year. From that association, a complicit friendship developed between the two artists. Although Jimenez’s figurative fiberglass sculpture is very different from his own, Moroles stated, “What I got from him was a sense of aesthetics. It shows in both abstract and figurative work: quality and craftsmanship.” When Moroles was thirty, he undertook a pilgrimage to Pietrasanta, Italy. As he was climbing the worn-out marble steps leading to the legendary quarries of Carrara, he understood that he wished to produce work that could be placed in the world so that people could touch and interact with it. Thus, his sculpture was not to be made from the marble with which Michelangelo carved his Moses, but rather from the granite of the great Egyptian pyramids and the walls of Tenochtitlan. He spoke about marble with some disdain: “It’s so soft, you can cut it with a nail file.” Whereas granite was a fundamental element to him, “the living stone” and “the core of the universe.” That is why Moroles worked almost exclusively with granite, a material whose hardness and unpredictability frightens away many sculptors.

Regarding his own work Fountain (1980), Moroles once said, “I wanted to make something symbolizing the mountains where the stone came from. (…) I was trying to bring all the elements—earth, water, and sky—together.” He added, “Granite is a monster to work with. I sit on it, I tap it, I feel it, and I look at the stone until I know what I must do with it. The shape of each stone is something that I cannot and do not want to change, because whatever happens in nature dictates what happens in my studio.”

He was a shaman of stones. He thought every stone had a soul and that his mission was to liberate it while leaving its heart intact. “I’ve got to be able to listen to each stone while it’s being worked on. Each piece resonates differently and reacts differently, so I pay attention to what the stone tells me it wants to do.” These statements may appear somewhat incongruous given that Moroles’ stereotomy—his art of cutting stone—is a craft of mathematical and technical precision involving powerful diamond saws and pinpoint accuracy. Nevertheless, even his most geometric and rectilinear sculptures manifest their forms with the naturalness of quartz crystals. Through craft and design, he was able to make granite appear malleable, light and expressive.

Concave, 2012

The intimacy Moroles developed with stone was such that he could predict exactly what its behavior and even its “voice” was going to be. In 1993, the Houston Chronicle‘s art critic, Patricia Johnson, reviewed his show “Tearing Granite: Thunder in the Stone” at Davis/McClain Gallery, describing an evening of sculpture, music and dance. The musician David Schrader and a dance group from Moroles’ alma mater, North Texas State University, were part of the performance. Moroles carved keys on stone sculptures like Black Musical Stele (1999) so that they could be played as musical instruments. Schrader accompanied a sound recording playing the steles as if they were xylophones (with sticks, stones and wire brushes), using the Molcajete (grinding stone) as a drum. The recording was Larry Austin’s composition Rompido (sic), accomplished with the deafening sounds of hammering, high-powered saws, grinders and other machines used for cutting and moving large granite sculptures. The dancers, choreographed by Sandra Combest, climbed onto mobile sculptures like Moonscape Ring (1993) —an enormous oval piece of granite weighing 3,480 pounds. Notwithstanding its tremendous weight, Moonscape Ring could roll like a bicycle wheel, making its own sound along the way. The highlight of the performance occurred when one of the steles was struck with enough force to play a certain note: one that caused the stone to break in half.

In 1987, Moroles completed Lapstrake, a 64-ton, 22-foot tall sculpture for the E.F. Hutton, CBS Plaza located across the street from the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In 1991, Moroles completed the Houston Police Officers’ Memorial, a granite square pyramid whose vertex rises from the meadow, surrounded by four inverted pyramids excavated into the ground. Over 2,000 works by Moroles are scattered around the world in China, Egypt, France, Italy, Japan, Switzerland, and the United States. In 2008, he was honored with the highest award given to an artist by the U.S. government, the National Medal of Arts.

Healing Garden, 2010

Jesus Moroles once stated, “My work is a discussion of how man exists in nature and touches nature and uses nature. Each of my pieces has about fifty percent of its surfaces untouched and raw —those are parts of the stone that were torn. The rest of the work is smoothed and polished. The effect, which I want people to not only look at but touch, is a harmonious coexistence of the two.”

Moroles lived like a force of nature, transforming stone into sculpture, forging beauty out of shapelessness. He once told me that he wanted to place his works wherever there were cultures that knew stone, that appreciated it, and made it part of their world. We had a pending journey together to Pisac, Sacsahuamán and Machu Picchu that he will miss. But when I do climb and stand on those cyclopean Inka boulders, I will remember his words and deeds.

Images courtesy of PDNB Gallery

Fernando Castro is an artist, critic and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University as a Fulbright scholar. He is a member of the art board of FotoFest and of the advisory board of the Houston Center for Photoography. He is a contributing editor of Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal, and Spot. Last year he delivered the lecture “Elian” at the University of Cambridge, England.

Fernando Castro is an artist, critic and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University as a Fulbright scholar. He is a member of the art board of FotoFest and of the advisory board of the Houston Center for Photoography. He is a contributing editor of Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal, and Spot. Last year he delivered the lecture “Elian” at the University of Cambridge, England.

Posted: June 23, 2015 at 10:04 pm