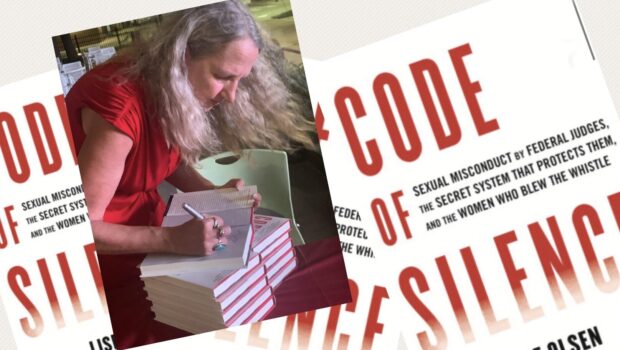

Code of Silence

Greg Walklin

In his 2015 year-end report, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote about the federal judiciary’s approach toward technological change. “The courts will always be prudent,” he wrote, “whenever it comes to embracing the ‘next big thing.’” Nobody would argue that the courts have quickly adapted to technology changes; in oral arguments, for example, Roberts once referred to search engines as “search stations.” The judiciary generally remains the most conservative branch of government—at least in that it adheres to established attitudes and practices long after the rest of the world, and even after the rest of government, has moved forward.

Resisting the latest technology changes may be an act of prudence, but failing to address changes in how employees are treated—especially female employees—resembles negligence. Lise Olsen’s book, Code of Silence, charts how several powerful federal judges harassed women for years with near virtual immunity, and how even after #MeToo led to a reckoning, the federal courts have still kept in place an obtuse, opaque system for handling sexual harassment and sexual assault complaints.

An investigative reporter with the Houston Chronicle, Olsen first broke the story about the allegations made by court manager Cathy McBroom against Samuel Kent, a federal district court judge for the District of Texas in Galveston. Kent assaulted and harassed McBroom, along with other employees of the federal court, repeatedly. Even when many, including security guards, witnessed McBroom running out of the building in tears, they remained too fearful of Kent to do anything. “[Y]ou were expected to do your job and not comment about what you saw,” McBroom told Olsen.

Eventually McBroom filed a formal complaint. The system to address such complaints, however, as Olsen shows, was far from adequate. Federal courts had previously resisted attempts by Congress to impose an ombudsman or some kind of independent counsel to handle complaints about judges, common in other branches of government. Like other complainants, she relied on the Chief Judge of the designated circuit, who possesses sole authority in the area. That judge usually has a full caseload and no separate support staff or budgeted funding to address and investigate complaints. While, undoubtably, many complaints about federal judges are trivial, complaints of workplace harassment or discrimination should never be treated lightly. It’s a credit to Olsen’s reporting, and her storytelling in this book, that she doesn’t have to spill much ink advocating for one particular position or another—she provides ample evidence for the readers to reach such obvious conclusions. Even a more transparent, funded, internal system for handling such investigations would have been better than what McBroom had to navigate.

In McBroom’s case, Chief Judge Edith Jones oversaw the investigation. Jones, Olsen notes, previously brushed off complaints about harassment in the workplace during oral arguments in one previous case before her, saying to the victim’s lawyer, “Well, your client wasn’t raped!” This may be anecdotal, but it is representative of the general obliviousness that seemed to plague the federal judiciary when it came to workplace discrimination; after all, Congress had exempted the judiciary itself from federal anti-discrimination statutes.

Olsen’s prose is reportorial, for sure, but doesn’t stray too far into journalist-ese; it’s not flashy but it services the story she tells. Thanks to the cooperation of many brave victims, Olsen weaves the story of McBroom along with gripping accounts from other female court workers, law clerks and attorneys, describing their experience with other powerful judges, such as former Ninth Circuit Chief Judge Alex Kosinski, as well as misconduct of other varieties by other judges.

Books such as Jon Krakauer’s Missoula, have deftly demonstrated the failings of the legal system (through administrative systems under Title IX or through the criminal courts) to address sexual assault, harassment, and rape. Code of Silence (Beacon Books, 2021) further elaborates on these types of systematic limitations and failings. Olsen quotes Judith Lewis Herman, a Harvard University-based psychiatrist, who aptly sums up the problem: “Victims understand all too well that what awaits them in the legal system is a theater of shame.” This, certainly, was McBroom’s experience in both the internal court complaint process and the resulting FBI investigation. (A point recently underscored by the testimony of former U.S. Olympic gymnasts, detailing failures by the Bureau on another assault investigation.) It’s an understatement to call these women brave.

To Olsen’s credit, she doesn’t fall back on easy explanations or argue for quick fixes. The book generally lets the facts speak for themselves. Most likely, it’s the massive power and control federal judges possess that silences their critics. Some judges have developed “robe-itis,” Olsen shows, and act without consequence, not only inside but outside of their courtrooms. They demean their support staff, who are mostly women, with impunity, and treat female lawyers differently than their male counterparts. With only Congress having the power to impeach and remove them from office, holding them accountable is an ordeal itself; even if they resign, they can keep their full salaries (Kent kept his salary even after reporting to prison, only losing it after the Senate was about to remove him from office). McBroom herself, in the final pages, understands just how long it will take to fully right these wrongs.

A book like this could not be written without referencing Anita Hill, whose damning testimony three decades ago nearly ended the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Indeed, with our better understanding brought on by #MeToo, Congress’ treatment of Hill has aged poorly. That Thomas lied under oath about his encounters with Hill now seems more likely than not—and perjury should be disqualifying for a position on the highest court. Thomas’ indignation at the “high-tech lynching,” as he called the nomination process, may be more of an indication that, deep down, even if he said and did all those things to Hill, and lied about it, he didn’t believe he was doing anything wrong. This kind of attitude seemed shared by Kent, Kosinski, and others.

By combining stories of many women’s experiences with sexual harassment, and by highlighting McBroom’s struggle, Olsen has built the case that true prudence would mean the federal judiciary taking a substantially different approach to workplace discrimination. This is not “the next big thing,” but simply a matter of treating employees with respect, and taking their complaints soberly and seriously.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Copyright Literal Publishing

Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: October 19, 2021 at 7:04 pm