No Borders, Only Roads

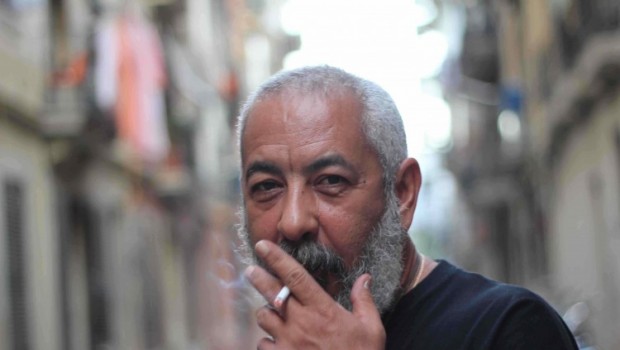

So Mayer

How many roads must a man walk down / Before you call him a man? Joan Baez’s famous question, best known in Bob Dylan’s version, resonates throughout Sally Potter’s new film The Roads Not Taken – although not always in the way we might expect.

In fact, The Roads takes the cliché of the rolling stone on the road, the troubadour with a notebook in his pocket and a woman in every port, and turns it upside-down and inside-out. Leo (Javier Bardem) is a writer, a well-travelled man of words who we see seeking answers in the chill fall winds of New York City, but also on the Day of the Dead in rural Mexico, and on a small Greek island. In New York, he’s being cared for by his adult daughter (Elle Fanning), who is his guide on a bewildering quest through the creaking US healthcare system. In Mexico, he is fighting with his wife Dolores (Salma Hayek) about the significance of rituals, and in the Mediterranean, he is drawn away from his writing toward a young woman traveling with her friends. In each storyline, we think we know what we’re seeing; we think we know how a man walks down a road, how his wayward behaviour affects those around him, yet how he always finds his way home.

It’s the oldest story, Odysseus’s story, the one that gives us the word nostalgia, home-sickness. But, in each storyline, Leo has left home, irrevocably, in a different way. On the island, he is the divorced, estranged father–who views himself as a romantic troubadour–who populates so many mainstream representations of male artists. Chasing after the young woman, he is seeking connection with his daughter, pushing himself into an epic quest, Old Man and the Sea style, to no avail. In Mexico, he is fleeing his own grief and his wife’s, taking to the road as if it will lead him away from himself: instead, it leads him back to the cause of his grief at a roadside shrine. And in New York, the most familiar of cinematic cities, Leo is most profoundly far from home, as a Mexican immigrant, and as a financially precarious person with dementia, cared for by Xenia (Branka Katić), a skilled professional who bitingly responds to Molly’s hand wringing that: “It’s OK, it’s my job.”

What is home when you can’t remember it, or find it? What are you sick with, or of, then? In the third act of the film, Leo leaves his Brooklyn apartment alone and wanders, barefoot, through the night, starting at Myrtle Avenue Station in Bed-Stuy. He crossed over the river, a fate that seems inescapable, and traverses dark, fenced-in streets, until he meets a ferryman who offers unexpected kindness. When he is returned to his apartment in the morning, he tries to explain to his daughter what he’s seen during the night, the roads he’s taken, the un homely way that his desire for home has taken him out of himself. “And then… come home,” he says, “this one, with you.” And for the first time in the film (seventy-five minutes, or twenty-four hours), he says a word that anchors him in that home, a word that matches up what he is seeing in his head and in the world: her name, Molly.

It is profoundly affecting, not least because we know that Molly herself is about to leave, for her work as a journalist. “I’ve been working on some stories,” she tells him before he names her, “in honor of your story… I have to go to the border.” She means the border between the US and Mexico, to report on the detention centres that the US government both boast about and try to obscure; the border that Leo crossed when he came to the US, where he met Molly’s mother Rita (Laura Linney). That border is also, as Leo’s journey in Mexico underlines, the borderland between life and death, one that we mark through rituals of memory in which New York Leo no longer seems to participate. His recognition of Molly is starker, simpler, sweeter and more bitter than the acts of anagnorisis–recognition–on which classical tragedies depend. This recognition confers no aristocratic heritage, nor does it condemn anyone to death. It is a connection in the moment and to the moment.

In saying “Molly,” Leo isn’t gaining miraculous access to his memories, in a sentimental climax. To demand otherwise would be to insist that we can only care for people–whether in real life, or on film–who are neuronormative, with full access to their memories and present. Instead, the film gives us Leo as he fully is, with his hopes and failures, his selfishness and charm, and also with the granular, moment-by-moment effects of dementia, as they impact him and Molly. The answer he has found is that all roads lead to vulnerability: to being interdependent with the others in his life. In a single word, he denies the dismissal of care implicit in the term “mollycoddle,” which suggests that looking after someone–and needing to be looked after–are soft or pathetic.

When he says his daughter’s name, it is not just recognition of biological affiliation, but of a deep affinity. Neither giving her name (as a parental act) nor taking it, he is seeing her as both an entity with an independent existence, and acknowledging her commitment to her heritage and relation to him–and his relation to those at the border. There is a sensitive analogy – not a parallel, but a sympathetic solidarity–between the two borderlands that Leo walks, as an immigrant and as a person with dementia, highlighted when he misrecognized a stranger’s dog as his midway through the film. It’s initially a comic moment, as Molly roams a vast Costco where they’ve gone to replace his pants after he wets himself fearfully at the dentist, and finds her father tenderly hugging a small dog. When its owner comes charging toward him, followed by security guards, calling him a “fucking Mexican,” the reality of America crashes in.

In the momentary, closing act of recognition that reprises this comic-tragic dognapping, there is a reminder that it was the border that crossed Mexico, and not the other way around; that borders are the problem, not the solution, and are anyway impossible to maintain. The film insists that even the walls we erect between the ‘real’ and our hopes, dreams, memories and longings are a useful but contingent norm: Leo shows us a way to cross them, just as he crosses the river (symbolic of death) and returns.

And in every scene, sound leaks. It starts with a buzzer over the opening credits, calling us to attention, to let the film in; and then a telephone ringing and ringing–an old-fashioned landline–as if sound itself were the guardian to Leo’s apartment. Sound forms bridges not only between scenes but between storylines, much of it from an evocative score composed by Potter herself (who plays keyboards alongside longterm collaborator Fred Frith on guitar). The visual palettes of each location–of each Leo–may be distinct, and distinctive languages accent each location, but sound both carries across and echoes: the lapping of the waves is (and is not) the rattling of the Jamaica Line. Even when the song is not the linear verse/chorus/verse we expect but a constantly-changing canon, one that gets stranger because it is sung by a stranger, the siren voice of life will not allow us to stop our ears.

So Mayer is the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism and Documentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

So Mayer is the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism and Documentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

©Literal Publishing

Posted: September 15, 2020 at 9:30 pm

“Blowin in the wind” author is Bob Dylan !!!