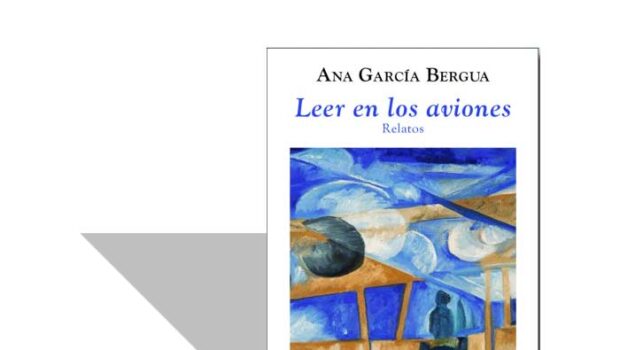

THE GLASS EYE (Excerpt)

YOLANDA GALLARDO

•Yolanda Gallardo: The Glass Eye (Arte Público Press, 2019)

CHAPTER ONE

DOÑA AMADA could see more with her one eye than most people could see with two. It was even rumored Amada removed her eye for morning prayer, leaving it to watch over her children as they ate breakfast. The children themselves would not confirm or deny the rumor, it seemed as though they wanted to distance them- selves from the mysterious work of their mother. She could see the past and she could see the future. The present was left to the bright, shiny marble that had replaced her other eye, torn from its socket by her husband’s jealous mistress. Sarah was her name, and her remains are said to be buried in scattered parts of Westchester County, though this doesn’t stop people from seeing her.

Sarah sightings have been reported as far away as New Orleans during Mardi Gras, where an old neighbor saw her throwing beads to the revelers from a balcony. Others saw the ghost of Sarah at George Washington’s Headquarters in White Plains, occupying his chair while trying on his very tall boots; at the Westchester Kennel dog show she caused many doggie accidents; at St. Peter and Paul’s church where her likeness has been seen in photographs, posing angelically next to the statue of the Madonna. The sighting most gossiped about is the one at Yonkers Raceway, where she was seen running down the stretch in com- petition with the horses for first place.

Many tales have been woven around the mystery of Sarah’s demise, but the one consistent legend is that of Sarah’s ghost, having collected all of her essential parts, sighted by drunken commuters on nights when the moon is full. They see her swimming in the river, trying to make her way back to the Bronx.

CHAPTER TWO

IN SPITE OF HIS LOOKS AND HIS SIZE SEVEN SHOE, Alberto had a way with the ladies, and he knew it. Perhaps it was his smile and the twinkle in his eye that made them go after him, but go after him they did. He found that the more he ignored them, the more they chased him, and the more his head did swell. His ego became unbearable. His ears already being larger than life, his head grew to a size that matched.

The men in the barrio grumbled at the fact that many times they would have to pay for their delights, while the same were given freely to Alberto, “the limp-wristed pequeña pinga,” as they began calling him. Having never seen him in the company of another man, they groused at the possibility that there was no truth to the rumor of his homosexuality, forgetting that it was they themselves who labeled him that way from an early age when he refused to play baseball and other sports with them. It was now too late to accept the fact that they had been mistaken. Besides, no real men manicured their fingernails, unless they were movie stars, and everyone knew that all of Hollywood was “like that.”

The fact that his father owned a bodega didn’t hurt his status with the ladies either. They would enter the shop with lascivious smiles, some golden, some toothless and, yes, even some very attractive, hoping to take home an extra chicken cutlet or green banana. The more brazen women would seductively lift oranges or grapefruits to their bee-sting breasts, which were invariably pushed up with rubber falsies or as much tissue paper as their c- cup brassieres could hold. Others hid their lips with the same lace handkerchiefs they would use to cover their heads during Sunday Mass. It was not a randomly chosen action by Father O’Connor, whose eyes searched the red and bleached-blonde heads for lip- stick marks, to remind certain ladies they were due for confession. Once there, the same sirens would pound their breasts with regret and later expiate their sins with innumerable Lord’s Prayers and Hail Marys.

Collusion with the Devil was murder on many a pair of nylons, but this did not deter them from continuing their mating dances once they left the church, knowing they were cleansed for the moment of any of the previous week’s wrongdoing. It wasn’t that they were bad girls. It was only their thoughts that they needed to confess. None of them actually did anything, but it was fun to think about it and think they did.

Alberto was not a churchgoer, except on special days when his mother and father went. These, of course, included Easter, when everyone wore hats and new clothes; Palm Sunday, when everyone could be seen carrying bright green palms which would replace last year’s faded ones and Ash Wednesday, when no self- respecting Catholic would dare show a forehead in public that did not bear a black smudge. A clean forehead was proof that one did not attend church regularly, and the whispered label “hypocrite” was difficult to endure for an entire year. Children, who felt that money earmarked for the poor was much better spent on egg creams or sugar cane, simply thumbed dirty automobile tires and then their own heads, knowing no one would recognize the difference. Few people did, and some of these children kept up the practice into adulthood, cigarette ashes replacing the tires.

Since these obvious days of worship were few and far between, Alberto had no idea that he was the topic of discussion at many a dinner attended by Father O’Connor and the other parish priests who, no doubt, ended up having to say the Lord’s Prayer and Hail Marys also. Instead, Albertico, as the women loved to call him, reveled in his good fortune and made certain that every woman who came into his father’s shop was treated to a bright smile and an adorable wink that let each one know she was the special one and not just one of the many.

His father, Don Pepitón, enjoyed his son’s popularity, living his life vicariously through him. But what he enjoyed most was the fact that his business had been booming ever since his only child hit puberty. He could not imagine why his son received so much attention from the ladies, but he made sure to thank the Lord every day for having blessed him with such a remarkable son.

Alberto’s mother, Doña Antonia, was a different story. Her theory was that all women were putas, herself and her mother excluded, and no woman would ever be good enough to bear her son’s children, which would no doubt be numerous. She did want grandchildren, fervently, but she cried daily at the fact that there was not another way for them to be conceived. The thought of her little Albertico laying with any woman literally sent her into convulsions. One time, in fact, her seizure was so intense that Don Pepitón had to close the shop after a visit from three not-so-very- tactful ladies. They had come into the shop seemingly to get groceries, but quickly showed their true intentions. Antonia was ready for them. She knew it was not an accident that they dam- aged as many avocados as they did, feeling for their ripeness, one digging a hole to the deepness of the pit with her purple finger- nails while giggling incessantly in the direction of Alberto. It was no accident either that the cleaver flipped through the air from Antonia’s hand and barely missed beheading one of the floozies. With shrieks of fear from the ladies and many perdón’s from Don Pepitón, they escaped to the street like chickens from a poultry shop. From then on, they would peer through the windows, making certain Doña Antonia was nowhere in sight before entering the bodega to continue parading their wares.

Women would wiggle in, slither in, some even danced in. Don Pepitón, as much as he enjoyed their performances, enjoyed the money he made from them even more.

It was only when Señorita Amada entered the picture on that “Godforsaken day,” as Albertico’s mother would say, that the mierda hit the fan. This was no ordinary young girl. There was definitely something wrong with her, for not once did she glance in Alberto’s direction; not that he didn’t try to get her attention. He winked and smiled and cleared his throat much too obviously, even went so far as to keep his thumb off of the scale when he weighed her one pound of ground beef, or as she called it, “chopped meat.” All of Alberto’s posturing was neglected by the lovely young girl who paid for her purchase, eyes lowered, and left without so much as an adiós. This display did not go unnoticed by Doña Antonia, who rebuffed her son, calling him an idiot and swearing he would never work in the bodega again since he was giving away the food and could no longer be trusted.

That was the day Alberto was banished to work in his uncle Pedro’s gas station, where his manicured hands turned black and splintered with steel as they became one with the cars he serviced. To his benefit, he gained freedom from his mother’s scrutiny. There was also an old, red Buick that would be his if he could get it running, which he eventually did, much to the surprise of his uncle. He had the same gift with automobiles that he did with the ladies, and that knowledge brought him newfound fame in the neighborhood.

Don Pepitón never questioned his wife’s decisions, for they were in reality orders, but he could be heard muttering under his breath at his stupidity for having chosen the wrong Delgado sister for a bride. And Uncle Pedro? Well, he was happy as a clam as his business thrived, as did his imaginary sex life, once his nephew, the “little maricón, my ass,” came on board.

YOLANDA GALLARDO is a poet, playwright and novelist born in the Bronx to parents of Cuban and Venezuelan/Puerto Rican heritage. Her play, Everybody Knows My Business, has been performed in Puerto Rico and optioned for Off Broadway. She’s the author of a digital poetry collection, The Fragile Thread (Word Wrangler Press), and her poems have been published in journals including Long Shot Magazine and Chiricú Journal. The Glass Eye (Arte Público Press, 2019) is her debut novel. She lives and works in Bronxville, New York.

©Literal Publishing

Posted: July 18, 2019 at 10:50 pm