Women in the Streets, a President in his Cage

Mujeres en la calle. El presidente en su jaula

Adriana Díaz Enciso

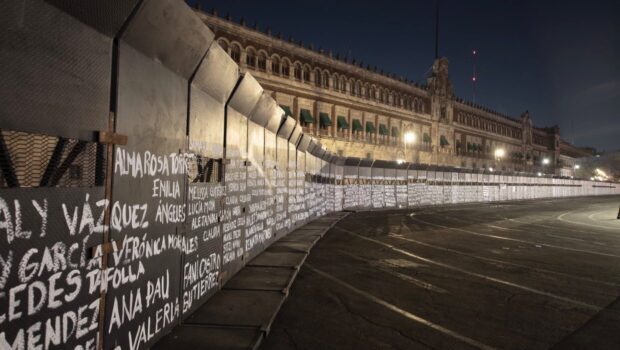

As the 8th of March, International Women’s Day, got close, the man who has made of the National Palace his home gets entrenched in his imponent dwelling behind a kilometres-long barricade, the symbolic significance of which shouldn’t go unnoticed: the protection of his illustrious self from the rage and pain which inevitably follow the unpunished rape, disappearance and murder of thousands of people, and an obstinate refusal to see, to listen and to engage in dialogue.

Women soon made of that impassable sign of silence and scorn a memory wall. It is hard to think of anyone who saw—either in person or in video or photograph— that barricade transfigured as memorial, as a call for justice, as the testimony of grief and, no doubt about it, of love too, and didn’t quiver. That memory wall is in itself a triumph of the spirit of humanity over violence, and over the corruption and apathy of a collapsed justice system.

Did the Mexican president leave for a moment his fort in order to contemplate, in the two senses of the word, that wall: with his eyes and his attention? He clearly didn’t, but here I am fantasising a bit with the possibility that this man, who believes that everything that happens and matters in Mexico is referred to himself, had the capacity of contemplation, and what the consequences might be. What would have happened if he had seen those women spontaneously organised after the barricade’s erection, with their facemasks, painting the names of thousands of hurt and murdered women, sticking up photographs, surrounding them with flowers, beneath the ominous headline “Victims of feminicide”? I want to think that he would have quivered too, and that the enormous gesture of solidarity, much bigger than the wall, would have managed to move him.

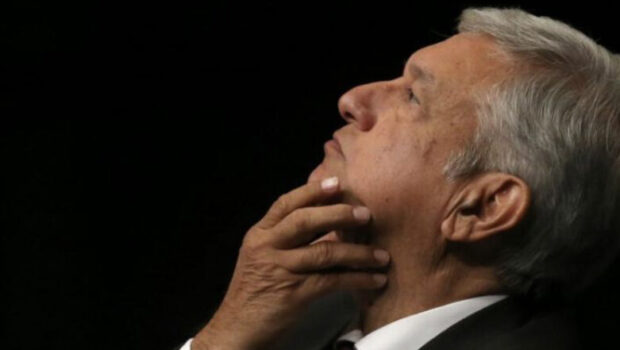

I am imagining an hypothetical parallel reality, in which the president of a country in which feminicides come to dozens of thousands since the 1990s, would be incapable of saying, with that bitter half-smile of his, that those women intent on turning indifference into an appeal for memory and into the very voice of the victims are “conservatives”, “infiltrators”, reactionaries politicking to undermine the glory of that Fourth Transformation that, in its leader’s head, is always written in capitals.

But he is capable, and he says all this. The barricade, he adds, was for protection. For preserving peace, because he is against violence. So am I, and the women who march in the streets to demand a stop to the shedding of blood of women and girls, and to call for justice for committed crimes, are rising up against violence, precisely.

Some definitions of violence: violence is the murder of an average of ten women per day. Violence is rape, intimidation, abuse of power and sexual abuse against women and young girls. Violence are the degradation and humiliation inflicted on the bodies of living women and, on occasion, on their corpses. Violence is kidnapping and disappearance. Violence is the lack of justice, for decades, for thousands and thousands of victims, which makes of Mexico one of the countries in the world where being a woman is most dangerous. Violence is the fact that crimes against women are on the rise instead of diminishing, and that impunity prevails despite the government’s promises about not tolerating anymore this state of affairs. Violence is to make public the images of the victim’s mutilated body. Violence is to ignore the accusations and history of women in risky situations until they end up murdered. Violence are the discrimination, exploitation and social exclusion of women and girls, endorsed by the acceptance of the status quo and silenced by impunity. Violence is the contempt for the female body. Violence is the sexualisation of the abuse of power. Violence is the complicit silence in the face of the executions of women that became visible in Ciudad Juárez since the 1990s, and which were later spread to other states, as well as the indubitably collective blame of such crimes, which couldn’t have happened or still go unpunished without complicity from high up.

Violence is to pretend that seeking justice after a feminicide and the inexpressible brutality of a crime is less important than the farce of the raffle for a presidential plane (“because this is history”, the president said then, before posing for the triumphant raffle picture). Violence is to smile and say that “there is no impunity anymore for anybody” in a country where around 3,000 women are murdered every year, and in which their relatives’ ordeal of looking for justice often ends up precisely in impunity and silence. Violence is to deem unimportant the calls for help of women who are being attacked.

Violence, to defend, then ratify, the candidacy for governor of a man accused of rape and sexual aggressions against women. Violence, to say ya chole (“enough of that!”) when such a defence of the indefensible is questioned.

Mr. López Obrador could have spared the National Palace barricade, that symbol of deaf ears, cowardice and closed doors, and refused instead to accept Félix Salgado Macedonio’s candidacy for governor of the state of Guerrero for the Morena party. He could have spared so much vain verbiage proclaiming his respect for women. He could engage in dialogue with the victims’ relatives, show that he cares about their grief, that he cares about the carrying out of justice, that he cares about putting an end to violence. Instead, the president of Mexico stares once more into his mirror, deformed by dint of excessive use, and concludes, again, that the protests are an attack against him and against the 4T. This issue, to him, has nothing to do with the bodies of women who suffer assault, with extinguished lives, with life beneath the constant pall of fear that is the daily bread for women in Mexico. He doesn’t want the matter to be mentioned; he says he doesn’t want media campaigns “with expert analysts pontificating, passing sentence, judging”, and he adds: “We suffered that for years. One attack after the other. Therefore, how can I not be suspicious and act cautiously?” Once again, the matter at hand vanishes and is transmuted into the president’s person and his government.

Mexico’s president tells us that the accusations against Salgado Macedonio should be settled through the law, yet the people of Guerrero have the right to support him as candidate. He doesn’t seem to understand that accepting in his party the candidacy of a man accused of rape and sexual aggressions constitutes an endorsement, from the topmost seat in power, of such crimes and the contempt for women which is one of the unquestionable causes of the protests.

His infamous ya chole speech came accompanied by his well-known paranoia: “I remember that even the conservatives were in last year’s feminist movement. They disguised themselves as sympathisers with the feminist movement—the most reactionaries, retrogrades, the most opposed to liberties, the most authoritarian appeared”, not to defend women’s rights, he claimed, but because “they were against us”. It seems that there is no criticism, denunciation or social movement in Mexico that the president cannot divert towards the only subject dwelling in his head: those who are against him.

Recently he has also talked about the “simulation about feminism”. It was when he gloated over his ignorance about the meaning of the term patriarchal pact, which he immediately followed by entering the labyrinth of his demagogy and his vanity, invoking the “pact” that he has already broken, “the pact against Mexico”. He then explains to us that that patriarchal pact thing is an imported expression: “copies. What do we have to do with that? We respect women, every human being. But conservatism gets onto that as well. In the case of Guerrero with Félix, since he’s the candidate, all the composition [sic].” […] “Why to have it in all the media, accusing us of being against women? Well, no, we are in favour of women’s rights”. Then he reminds us that most public servants in his government are women, and concludes: “Since when conservatives become feminists? Then all this is interesting because of the role media play, how they want to affect us, the constant attacks, the misinformation, the manipulation. I am a humanist and that’s why I respect feminism, and we aren’t like the conservatives. I have no weight on my conscience.”

The whole of this nonsensical speech is documented in press and videos, and it’s the confirmation, in case we needed it, that from the narrow ideological cage in which the president has shut himself up, protected by walls much thicker and unbridgeable than those he had erected around the National Palace, he’s incapable of realising that the indignation about the systemic violence against women in Mexico and the call for justice come from all segments of society, and that women’s protest, far from being a campaign aiming at the imposition of an ideology, is the unstoppable cry of a country tired of counting the dead and looking for disappeared people; the cry of women who have paid with harm against their own body, or that of their daughters, mothers, sisters, friends, the high price of that patriarchal pact that López Obrador discredits with disdain because, to him, it’s imported, irrelevant stuff, even when the raped, mutilated and murdered bodies go on piling up, and the victims are so many that their names filled the memory wall all along the National Palace façade.

Worryingly, in his recent diatribes about the supposed media complot against him, the president dodges the only question that matters here: why his party accepts and ratifies the candidature for governor of a man accused of rape. If in these circumstances Mr. López Obrador has “no weight on his conscience”, we can only conclude that it is rather conscience itself that is absent.

***

I think it’s laudable that there is gender parity in the current government, and no doubt there must be women there, and men too, committed to the struggle against gender-related violence and to the construction of an effective system of justice. I know that several Morena representatives were vocal about not allowing Salgado Macedonio to take part in the elections, and that at least one of its militants has even resigned because of this. The problem is, apart from atrocious, complex; its roots certainly precede by far López Obrador’s administration, and we’ll have to listen to those women in his cabinet who have been so quick to defend the 4T’s position with regards to violence against women to understand the work they’re doing. Disposition to listen and to engage in dialogue must exist, by principle, both in sympathisers and critics. However, it is clear that the current government is quite far from consolidating that effective system of justice that is so urgently needed, or from fulfilling its promises about the prevention of violence, including that which is gender related. The number of victims keeps on growing, rather than diminishing. This is as far as concrete facts are concerned.

There are also the symbolic facts, those which are laid down through language, gestures, words. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, in his unfortunate confrontations with a feminist movement he doesn’t understand and which he seems to perceive only as a threat to his person and his party, once and again sends a message of contempt towards that movement, of a negative to dialogue and an insulting indifference in the face of thousands and thousands of corpses.

Unfortunately, that indifference is nothing new. On several occasions López Obrador has shown a disdainful attitude towards the victims of violence or their relatives, despite the grandiosity of his discourse when he claims that in his government there will always be dialogue, and that he will never hide. Last year, for instance, he refused to receive Javier Sicilia and members of the Le Barón family, representatives of the Hike for Truth and Justice, at the Palacio Nacional, “to avoid making a show”; the same applied to the families of feminicide victims who were stationed at the Zócalo demanding to be seen directly by him. They were received by the Ministry of the Interior, but not by the president, because he had “many issues to go through”.

Such an attitude was already foreshadowed in 2017, when López Obrador was Morena’s leader before becoming president. During a visit to New York for a migrants’ rally, he called Antonio Tizapa, father of one of the 43 Ayotzinapa disappeared students, “a troublemaker”, when he asked the politician about his relationship with Iguala’s mayor, José Luis Abarca, and Guerrero’s governor, Ángel Aguirre Rivero, at the time of the crime in Iguala. In the video that documents the incident, Tizapa is showing a t-shirt with the faces of the disappeared students. López Obrador laughs at him, insists on accusing him of provocation, and then tells him: “Shut up”.

For this man, now the president of Mexico, all those of us who demand justice and an end to rampant violence, including the victims’ parents, are that: troublemakers. In a country where victims’ relatives dig the earth with their hands looking for the bodies of the disappeared; where crimes against women and girls are on the rise, with impunity in many cases, the president, rather than offering a serious response to our questioning and showing at least one gesture expressing not only understanding of the problem’s gravity as a head of state, but simple human solidarity, discredits the demands, the protests, the cry born out of grief and impotence, as his opponents’ conspiracy; he invalidates the calls for help to emergency services made by women in danger, and shuts himself up behind barricades of all sorts, physical and mental, so as not to hear anything that isn’t his own voice.

Last 8th of March Andrés Manuel López Obrador should have walked out of Palace to stand in front of the memory wall, read the names that kept on growing in white letters covering the metal, try to understand the grief and rage of the women who wrote those names, and the care of the hands that surrounded them with flowers. He should have tried at least to imagine the pain of a harmed body, the horror and pointlessness of a life snuffed out through violence, the void left by a disappeared human being, the desolation of the victims’ relatives. And multiply all that by the thousands. If he had done that, horror, solidarity and compassion would have made him take the side of the feminists, open to them the doors, at least symbolically, of the National Palace, and inform during his mañanera sessions, without demagogic nonsense, of the concrete progress being made in human rights issues and justice for the victims, as well as of the strategies that his government is following to put an end to this untenable empire of violence. If he had only opened his eyes, that would be his fixed idea.

But that’s not what happened. The president chooses to build barriers, of metal and contempt, to make his echo chamber more and more impenetrable.

El hombre que ha hecho del Palacio Nacional su casa, al acercarse el 8 de marzo, Día Internacional de la Mujer, se atrincheró en su imponente morada tras una valla kilométrica cuya carga simbólica no debería pasarle desapercibida: protección de su insigne persona de la ira y el dolor que inevitablemente siguen a la violación, ultrajes, desaparición y asesinato impunes de millares de personas, y una obstinada negativa a ver, a escuchar, dialogar.

Pronto las mujeres convirtieron esa infranqueable señal de silencio y desdén en un muro de la memoria. Es difícil pensar en alguien que haya visto, en persona, en video o fotografía esa valla transfigurada en monumento, en clamor de justicia, testimonio del dolor y, qué duda cabe, del amor también, que no se haya estremecido. Ese muro de la memoria es ya en sí mismo un triunfo del espíritu de humanidad sobre la violencia, al igual que sobre la corrupción y abulia de un sistema de justicia colapsado.

¿Salió en algún momento el presidente mexicano de su fortín para contemplar el muro, en los dos sentidos de la palabra: con los ojos y con su atención? Está claro que no, pero fantaseo aquí un poco con la posibilidad de que este hombre que cree que todo lo que ocurre e importa en México hace referencia a su persona tuviera la capacidad de contemplación, y con cuáles serían las consecuencias. ¿Qué habría sucedido si hubiera visto a las mujeres organizadas espontáneamente ante la erección de la valla, con sus cubrebocas, pintando los nombres de miles y miles de mujeres ultrajadas y asesinadas, pegando fotografías, rodeándolas de flores, bajo el titular ominoso de “Víctimas de feminicidio”? Quiero pensar que se habría estremecido también, y que el gesto enorme de solidaridad, mucho mayor que la muralla, habría llegado a conmoverlo.

Estoy imaginando una hipotética realidad paralela, en la que el presidente de un país en el que los feminicidios, desde la década de 1990, suman decenas de miles, sería incapaz de decir, con esa amarga media sonrisa suya, que esas mujeres decididas a convertir la indiferencia en un llamado a la memoria y en la voz misma de las víctimas, son “conservadoras”, “infiltradas”, reaccionarias haciendo “politiquería” para minar la gloria de esa Cuarta Transformación que, en la cabeza de su líder, se escribe siempre con mayúsculas.

Pero es capaz, y lo dice. La valla, añade, era para protección. Para guardar la paz, porque él está en contra de la violencia. Yo también lo estoy, y las mujeres que salen a la calle a exigir que pare ya el derramamiento de sangre de mujeres y niñas, y que se haga justicia por los crímenes cometidos, se están pronunciando, justamente, en contra de la misma.

Algunas definiciones de violencia: violencia es el asesinato de un promedio de diez mujeres por día. Violencia es la violación, la intimidación, el abuso de poder y el abuso sexual en contra de mujeres y niñas. Violencia son la degradación y humillación infligidas contra los cuerpos de mujeres vivas y, en ocasiones, de sus cadáveres. Violencia son el rapto y la desaparición. Violencia es la falta de justicia durante décadas para miles y miles de víctimas, que hace de México uno de los países donde más peligroso es ser mujer en el mundo. Violencia es que los crímenes contra mujeres aumenten en lugar de disminuir y sigan impunes pese a las promesas gubernamentales de que ya no serían tolerados. Violencia es difundir las imágenes del cuerpo mutilado de las víctimas. Violencia es ignorar las denuncias y antecedentes de mujeres en situaciones de riesgo hasta que terminan asesinadas. Violencia es el crimen de Estado constituido por la incapacidad de éste de garantizar la vida, seguridad y los más elementales derechos humanos de las mujeres. Violencia son la discriminación, explotación y exclusión social de niñas y mujeres, avaladas por la aceptación del estatus quo y silenciadas por la impunidad. Violencia es el desprecio del cuerpo femenino. Violencia es la sexualización del abuso de poder. Violencia es el silencio cómplice ante las ejecuciones de mujeres que se volvieron visibles en Ciudad Juárez en la década de 1990 y que se han extendido después por otros estados mexicanos, así como la culpa indudablemente colectiva de esos crímenes que no podrían darse ni seguir impunes sin complicidad desde el poder.

Violencia es pretender que buscar justicia tras un feminicidio y la inexpresable brutalidad de un crimen es menos importante que la farsa de la rifa de un avión presidencial (“porque esto es historia”, dijo entonces el presidente, antes de tomarse la foto victoriosa de su rifa). Violencia es sonreír y decir que “ya no hay impunidad” para nadie en un país donde alrededor de 3,000 mujeres son asesinadas al año, y en el que el viacrucis para sus familiares de la búsqueda de justicia termina a menudo justamente en la impunidad y en el silencio. Violencia es restarle importancia a las llamadas de auxilio de mujeres que están siendo agredidas.

Violencia, defender y luego ratificar la candidatura para gobernador de un estado de un hombre acusado de violación y agresiones sexuales contra mujeres. Violencia decir “ya chole” cuando es cuestionada esta defensa de lo indefensible.

El señor López Obrador podría haberse ahorrado la valla en el Palacio Nacional, ese símbolo de oídos sordos, cobardía y puertas cerradas, y negarse en cambio a aceptar la candidatura de Félix Salgado Macedonio por el partido Morena a la gubernatura del estado de Guerrero. Podría ahorrarse tanta palabrería vana proclamando su respeto por las mujeres. Podría dialogar con los deudos de las víctimas, demostrar que le importa su dolor, que le importa que se haga justicia, que le importa el alto a la violencia. En su lugar, el presidente de México se mira una vez más en su espejo deformado a fuerza de exceso de uso, y concluye de nuevo que las protestas son un ataque contra él y contra la 4T. Es decir, el asunto para él no tiene nada que ver con los cuerpos de mujeres ultrajadas, con vidas extinguidas, con la vida bajo el paño constante del miedo que es el pan cotidiano de las mujeres en México. No quiere que se hable del tema; no quiere, dice, campañas mediáticas “con expertos analistas pontificando, sentenciando, juzgando”, y añade: “Si nosotros padecimos eso, durante años. Ataques tras ataques. Entonces, cómo no voy yo a estar desconfiado y actuar de manera precavida.” Una vez más, el tema en cuestión se difumina y se transmuta en su persona y su gobierno.

El presidente de México nos dice que las acusaciones en contra de Salgado Macedonio tienen que dirimirse a través de denuncias y de la ley, pero que el pueblo de Guerrero tiene el derecho de apoyar al candidato. No parece entender que aceptar en su partido la candidatura de un hombre acusado de violación y agresiones sexuales constituye un respaldo desde el escaño más alto del poder a la impunidad de semejantes crímenes, y el desprecio por la mujer que es una de las causas indudables de las protestas.

Su infame discurso del “ya chole” vino acompañado de su consabida paranoia: “Yo recuerdo que en el movimiento feminista del año pasado se metieron hasta los conservadores. Se disfrazaron de simpatizantes del movimiento feminista, los más reaccionarios, retrógradas, los más contrarios a las libertades. Los más autoritarios aparecieron”, no para defender los derechos de las mujeres, alega, sino porque “estaban en contra de nosotros”. Tal parece que no hay crítica, denuncia ni movilización social en México que el presidente no desvíe hacia el único tema que ocupa su cabeza: los que están en su contra.

Recientemente ha hablado también sobre “la simulación sobre el feminismo”. Esto fue cuando se regodeó en su ignorancia sobre el significado del término pacto patriarcal, para de inmediato adentrarse en el laberinto de su demagogia y su vanidad, invocando el “pacto” que él ya rompió, “el pacto contra México”. Luego nos explica que eso del pacto patriarcal es una expresión importada: “copias. ¿Qué tenemos nosotros que ver con eso? Si nosotros somos respetuosos de las mujeres, de todos los seres humanos. Pero también en eso se monta el conservadurismo. En el caso de Guerrero con Félix, como es candidato, toda la composición [sic].” Continúa: “¿por qué hacer[lo] mediático, en todos los medios acusándonos de estar en contra de las mujeres?, pues no, nosotros estamos a favor de los derechos de las mujeres”. Nos recuerda que en su gobierno la mayoría de los servidores públicos son mujeres, y concluye: “¿De cuándo acá los conservadores se vuelven feministas? Entonces todo esto es interesante por el papel de los medios de información, cómo quieren afectarnos, los ataques constantes, la desinformación, la manipulación. Yo soy humanista y respeto por eso al feminismo, y no somos iguales a los conservadores. No tengo ningún problema de conciencia.”

La totalidad de este discurso cantinflesco está documentada en prensa y videos, y es la constatación, por si nos hacía falta, de que desde la estrecha jaula ideológica en que se ha encerrado el presidente, protegida por vallas mucho más gruesas e infranqueables que las que mandó erigir alrededor del Palacio Nacional, es incapaz de darse cuenta de que la indignación por la violencia sistémica contra las mujeres en México y el clamor de justicia vienen de todas las capas de la sociedad, y que la protesta de las mujeres, lejos de ser una campaña por imponer una ideología, es el grito incontenible de un país cansado de contar muertos y buscar desaparecidos; el grito de mujeres que han pagado con el ultraje de su propio cuerpo, o el cuerpo de sus hijas, madres, hermanas, amigas, el alto precio de ese pacto patriarcal que López Obrador descalifica con desprecio porque es, a sus ojos, una cosa importada que no viene a cuento, aunque se acumulen los cuerpos violados, mutilados, asesinados, y las víctimas sean tantas que sus nombres llenaron el muro de la memoria a todo lo largo de la fachada del Palacio Nacional.

Gravemente, en sus recientes diatribas sobre el supuesto complot mediático en su contra, el presidente elude responder a lo único que aquí importa: por qué su partido acepta y ratifica la candidatura a gobernador de un hombre acusado de violación. Si en estas circunstancias el señor López Obrador no tiene “ningún problema de conciencia”, no nos queda sino concluir que es más bien la conciencia misma lo que se encuentra ausente.

***

Me parece loable que haya paridad de género en el gobierno actual, y sin duda habrá ahí mujeres, y hombres también, comprometidos con la lucha contra la violencia de género y con la construcción de un sistema efectivo de justicia. Sé que varias diputadas de Morena exigieron que no se le permitiera a Salgado Macedonio participar en los comicios, y que incluso ha habido renuncias de al menos una de sus militantes. El problema es, además de atroz, complejo, con raíces ciertamente muy anteriores al gobierno de López Obrador, y habrá que escuchar a las mujeres en su gobierno que se han visto tan prontas a defender la postura de la 4T en lo que toca a la violencia contra mujeres para entender el trabajo que están haciendo. La disposición a escuchar y al diálogo tiene que existir por principio tanto en simpatizantes como en críticos. Sin embargo, resulta claro que el gobierno actual está muy lejos de consolidar ese urgente e imperativo sistema efectivo de justicia, o de cumplir sus promesas sobre la prevención de la violencia, incluyendo la violencia de género. El número de víctimas sigue creciendo, en lugar de disminuir. Esto en los hechos concretos.

Están también los simbólicos, los hechos que se asientan con el lenguaje, el gesto, la palabra. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, en sus desafortunadas confrontaciones con un movimiento feminista que no entiende y que parece percibir solo como amenaza a su persona y su partido, una y otra vez envía un mensaje de desprecio al movimiento, rechazo al diálogo y una insultante indiferencia frente a miles y miles de cadáveres.

Por desgracia esta indiferencia no es cosa nueva. En varias ocasiones ha manifestado una actitud despectiva hacia las víctimas de violencia o sus familiares, pese a la grandiosidad de su discurso de que en su gobierno siempre habrá diálogo y que siempre dará la cara. El año pasado, por ejemplo, se negó a recibir en Palacio Nacional a Javier Sicilia y los integrantes de la familia Le Barón, representantes de la Caminata por la Verdad y la Justicia, “para no hacer un show”, así como a las familias de víctimas de feminicidio que hacían plantón exigiendo ser atendidas directamente por el mandatario. A estas últimas las recibió la Secretaría de Gobernación, pero no el presidente, porque tenía “muchos temas que revisar”.

Esta actitud se prefiguraba ya en 2017, cuando López Obrador era dirigente de Morena, antes de llegar a la presidencia. Durante una visita a Nueva York, tras un mitin con migrantes, le llamó “provocador” a Antonio Tizapa, padre de uno de los 43 estudiantes desaparecidos en Ayotzinapa, quien lo cuestionó sobre su relación con el alcalde de Iguala, José Luis Abarca, y el gobernador de Guerrero, Ángel Aguirre Rivero, cuando tuvo lugar el crimen en Iguala. En el video que documenta el incidente, Tizapa lleva una camiseta con los rostros de los estudiantes desaparecidos. López Obrador se ríe de él, insiste en llamarlo provocador y luego le dice: “Ya cállate”.

Para el ahora presidente, eso somos todos los que exigimos un alto a la violencia rampante y justicia, incluyendo a los padres de las víctimas: provocadores. En un país donde los familiares de las víctimas escarban la tierra con sus manos para encontrar los cuerpos de los desaparecidos; donde los crímenes contra niñas y mujeres van en aumento, en muchísimos casos impunes, el presidente, en lugar de dar una respuesta seria a los cuestionamientos y de tener aunque sea un solo gesto que exprese no solo comprensión como mandatario de la gravedad del problema, sino simple solidaridad humana, descalifica las exigencias, las protestas, el grito que nace del dolor y la impotencia, como un mero complot de sus oponentes, invalida las llamadas de auxilio a servicios de emergencia de mujeres en peligro, y se encierra tras vallas de toda índole, físicas y mentales, para no oír nada que no sea su propia voz.

El pasado 8 de marzo Andrés Manuel López Obrador debió haber salido de Palacio y plantarse ante el muro de la memoria, leer los nombres que se iban acumulando con letras blancas sobre el metal, tratar de entender el dolor y la ira de las mujeres que escribieron esos nombres, y el celo de las manos que los rodearon de flores. Debió intentar al menos imaginar el dolor de un cuerpo violentado, el horror y el sinsentido de una vida apagada por la violencia, el vacío que deja un ser humano desaparecido, la desolación de los familiares de las víctimas. Y multiplicar todo esto por decenas de miles. Si hubiera hecho eso, el horror, la solidaridad y la compasión lo habrían hecho tomar el partido de las feministas, abrirles las puertas, así fuera simbólicamente, del Palacio Nacional, informar en sus “mañaneras” de los avances concretos (sin palabrería demagógica) en materia de derechos humanos y justicia para las víctimas, así como de las estrategias que está siguiendo su gobierno para dar fin a este imperio insostenible de la violencia. Si tan solo hubiera abierto los ojos, esa sería su idea fija.

Pero no fue así. El presidente prefiere construir barreras, de metal y de desdén, para volver cada vez más impenetrable su cámara de ecos.

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.