XUL SOLAR (1887-1963)

Fernando Castro R.

Translucency and Opacity

“It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

Pablo Picasso

Sixteen years have passed since the exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston Xul Solar: visions and revelations,[1] an ambitious retrospective of the Argentine artist Xul Solar. At the time I quoted Patricia Artundo, the chief curator of said exhibit, “it is indispensable to define Xul Solar as an esoteric and occultist.” As it turns out Artundo’s characterization is paramount because it exonerates the interested viewer from the difficulty of interpreting some of Xul’s works that have been rendered intentionally opaque to everybody but the initiated.

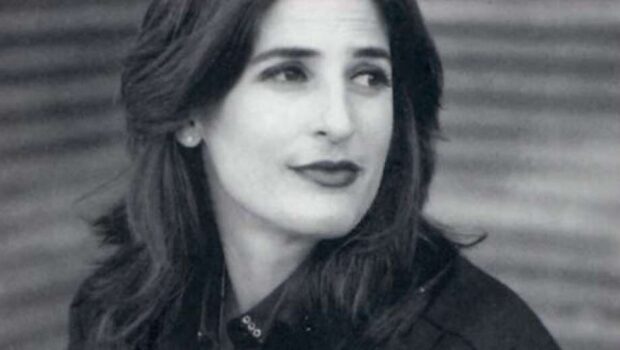

A more modest exhibit of Xul’s work at Sicardi Ayers Bacino Gallery, The Wondrous Realities of Xul Solar, curated by Gabriela Rangel, is a distillation of a third exhibition, Xul Solar and Jorge Luis Borges: The Art of Friendship, shown at Americas Society in New York (2013). Together they prompt this new query, perhaps because they remind us that Xul’s flamboyant personality is often more tempting to investigate than it is to explore his cryptic works. The disparity occurs precisely on account of Xul’s penchant for esoterica. This essay is a futile attempt to address his works more than his personality.

For almost all intents and purposes the artistic life and oeuvre of Xul Solar (A.K.A. Oscar Agustín Alejandro Schulz Solari) started shortly before 1912, the year when he sailed away from Buenos Aires in route to Hong Kong with the intention of becoming a Tibetan monk. However, Asia was not to be his destination, for he disembarked in London and from there he traveled to Italy. Taking his mother’s hometown in Zoagli as a home base, he spent different periods of time in London, Paris, Florence, Milan and Munich. We get a glimpse of the young Xul at the café La Rotonde in Paris from Argentine poet Francisco Luis Bernardez: “…a young Argentine, part painter and part astrologer, (…) He was tall enough to stand out anywhere. He wore a beret, and a huge striped sky-blue and white poncho which made him look like a large living flag…” Others saw him in Montparnasse in the company of Modigliani and Picasso. Xul wrote to his father saying he had acquired Der Blaue Reiter Almanac, and enthusiastically expressed his confidence that his own work was on the right track of what would become an important art style.”[2] The Munich-based Der Blaue Reiter group included Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Franz Marc, et al. Its members had a marked interest in primitive forms of art, including children’s art, and believed that a spontaneous and intuitive approach to art could reveal “spiritual truths.” Along their wake, Xul found a path to conciliate his own artistic and mystic interests. “Spiritual” is a term that was widely used by philosophers of German Romanticism but in the 20th century it was largely relegated to artistic, religious and esoteric parlance.

In her presentation essay, Rangel does well to point out important clues to the works in the exhibit. The first one is Xul’s well-intended albeit grandiose invention of languages like Neo-Criollo and Panlengua. The adoption of the name “Xul Solar” in 1916 marked the moment when his interest for improving existing languages germinated. That year he also made a crucial trip to Florence –an enclave of futurism– where he met and eventually became a friend of the Argentine painter Emilio Pettoruti. Neo-Criollo, which Xul thought would lead to Pan-American unification, is the language of the text included in works like Culebra (1919), and Adoramoste (1919). Time eclipses the fact that in 1919 there were a few traits that were bold about these works. To begin with, the very inclusion of text within the work. Then, the childish (or “primitive,” as many would prefer to call it) style in which they are rendered. Xul’s childlike depictions of humans, buildings and animals are not unlike some by Paul Klee. In his book, Alejandro Xul Solar (1994), Mario Gradowczyk writes, “Klee was the artist Xul most admired, and with whom he shared an affinity in painting, in music, and in spirituality…”[3] Finally, there is the snake leitmotif that recurred in Xul’s oeuvre since those early years.

Several works in the current exhibit depict snakes; Cuatro Man Sierpes (1935) is one of them. The meaning of anthropomorphized snakes is ultimately reserved to Xul or others who share his esoteric beliefs. For most of us snakes are automatically Biblical and evil; for some of us, phallic; for the scientifically minded, a limbless often venomous reptile. Some scholars have suggested that Xul’s fascination with snakes is derived from the pre-Columbian myth of the plumed serpent: Quetzalcoatl.[4] Pettoruti, fellow painter and travel companion, recalls what an intellectually curious person Xul was, and how he would insist in visiting not only every museum and library in the cities they visited, but archives as well. It is quite likely that he could have found out about Quetzalcoatl while in Europe.[5] “Quetzalcoatl” in its literal sense means “serpent of precious feathers” but in its allegorical sense it means “wisest of men.” Hence, Xul’s snakes allude to a human archetype: “the wise one.” Another line of inquiry leads to the 13th constellation of the Zodiac: Ophiuchus, “the snake-bearer.”[6] Xul, a master astrologist, must have known about Ophiuchus, especially because it looms over people who like he, were born on December 14th.[7]

Xul’s first major exhibition took place at Galleria Arte in Milan in 1920; it included seventy of his works. Pettoruti commented, “There is a strange mystery in these works, their fantastic visions, in which the imagination, with no control of reality… appears to gaze into privileged spaces and discover a world populated by ghosts and arcane suggestions.” Some of the works like Imitá mi pax (1919) contain signs, letters and words in Neo-criollo, a language he had already begun to develop.

A brief digression about Xul’s invented languages. Disingenuously he once asked Borges to write his works in Neo-Criollo. The latter diplomatically responded thus, “I answered that this language was his invention and that I had no right to write in it. He then told me: ‘No, if it is only my invention it would be worthless; inventions must be shared’.”[8] Had Borges accepted Xul’s offer, his literature would have become partially lost in translation to most of us, and the whole corpus of Spanish literature would have become somewhat opaque to Neo-Criollo speakers. One wonders what would have become of Xul Solar if his interlocutor had not been the ever-curious and gracious Borges, but someone like the always-rigorous Mario Bunge? (assuming the counterfactual that there wasn’t a twenty-year age difference).

In 1940 a new series of works called Grafías based on stenography surfaced in Xul’s solo show at Amigos del Arte. His Grafias negotiated meaning with the symbols of shorthand and ideograms. In spite of the formal and whimsical appeal of works like Grafía (1935) —composed of enigmatic curlicues resembling seahorses, clouds or pieces of Dali’s mustache—the work is unnecessarily hermetic for the run-of-the-mill viewer. In fact, Gradowczyk plainly states that the meaning of this first Grafía (1935) “has not been decodified yet,” as one would with conventional stenographical marks.

In Paris Xul had met the occultist Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), the man whom the British press called “the Wickedest Man on Earth,” and who signed his texts with the epithet “The Beast 666.” Under his auspices, Xul was ordained into the Astrum Argenteum Order. Artundo states, “We know that Xul’s encounter with Crowley was decisive in his life, inasmuch it gave him a method (…) to have visions, derived from the practices of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn…”[9] Other commentators describe Xul’s visionary method as derived from the Chinese Book of Changes, The I-Ching. Did the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn use the I-Ching as well? “Visionary” practices were not uncommon among artists. Alfred Kubin (1877-1959), another member of Der Blaue Reiter, wrote to Kandinsky, “My experiences of mystic things have been tremendous and still are. I experience exalted states of mind one after the other, also a great deal of evil, …” (May 5, 1910). Crowley wrote to Xul, “Your register as the best visionary that I have ever examined still subsists today, and I would like to have this group of visions [his San Signos based on the I-Ching] as a model.”

Shortly before their return to Argentina in 1924, Xul and Pettoruti participated in the Exposition d’Art américain-latin at the Musée Galerie, Paris —the first survey exhibition of Latin American art.[10] He showed three watercolors with pre-Columbian indigenous inspiration: Cabeza, Composición and Mujer y sierpe. The re-insertion of Xul into the Argentine art world was facilitated by his friendship with Borges. In Buenos Aires, Xul’s works were published in the avant-garde magazine Pancho Fierro. In addition, he illustrated Borges’ book, The Language of Argentines (1928). When Xul had his first exhibition at Buenos Aires’ Salón Libre, the critic Alfredo Chiabra Acosta noted, “The strangest and most unique contribution are the works of Xul Solar (…) We would have to go back upstream to the sacred rivers of civilizations that existed in Asia to find something as complicated and as child-like as this painting.”

After his return to Buenos Aires Xul’s esoteric activities continued in crescendo. In 1929 the Keppler Lodge, part of the Fraternitas Rosicruciana Antiqua, granted him the title of “instructor.” In the thirties we find him conducting all-night astrological and meditation sessions with friends and adepts. In 1940 he translated Helena Blavatsky’s The Voice of Silence and became a member of the Martinista Order under the name of “Brother Nil.” In the current exhibit there are several objects shown in a glass case; among them, Pablo Picasso’s astrological chart that Xul drew up. There is no indication that he considered these charts works of art. However, in the catalog raisonné of his oeuvre one discovers that he used some astrological charts as a compositional tool for artworks: Horóscopo de Lita (1953), Horóscopo de Lysandro Galtier (1961), Horóscopo de Ruth Brigitte Hermann de Gubitsch (1954), etc. These “astrological portraits,” seldom talked about in the literature, may very well be Xul’s most unique creations.

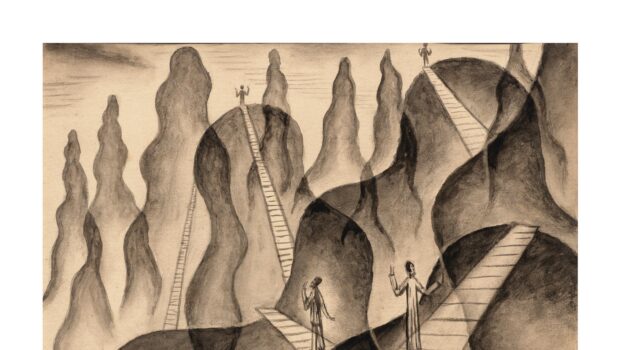

Throughout the thirties and up to the 1950s, Xul painted numerous landscapes that are arguably his most enduring legacy. Gradowczyk has called them “mystical landscapes” and has compared them to the Carceri of Giovanni Battista Piranesi and to the famed stone dwellings in Cappadocia. There are three of them in the current exhibit. In Paisaje (1951) pilgrims travel along steep stairs carved on the mountainsides. Their “unreality” is enhanced by the translucency of the mountains. A previous work, Paisaje de caminos (1948), is similar albeit the topography is rockier and the mountains are opaque. Pais anguloso (1951) is more angular and schematic, and it is unclear whether the narrow paths are a road to enlightenment or entrapment. Some of Xul’s mystical landscapes are reminiscent of Chinese and Japanese landscapes where pilgrims are minuscule and gain enlightenment through ascent, meditation, isolation, darkness, and epiphany.

At age seventy, Xul described himself as “…painter, writer, and a few other things, duodecimal, and ‘catrólico’ (ca–cabalista, tro –astrólogo, li –liberal, co–coísta o cooperador), recreator, non-inventor, and world champion of panajedrez [panchess] and other serious game that nobody plays, father of a panlengua [panlanguage] that seeks perfection but almost nobody speaks; and godfather of another vernacular language without vulgate, author of grafías plastiútiles that almost nobody reads, exegete of a dozen plus one religions and philosophies that almost nobody heeds…”[11]

In spite of what one may opine about Xul’s esoteric beliefs, what is admirable about his oeuvre is that it crystallized the totality of who he was, as an artist, as a spiritual pundit, as an inventor of words and things. From outside the Argentine artworld one cannot possibly be sure about the ripples of influence Xul’s oeuvre generated. His is a difficult act to follow mainly because of its esoteric component, so appealing to so many. At the simply iconographic level, one can project his work (sans mysticism) onto that of Antonio Seguí (adding sociological irony) and Ana Eckell (adding psychological existentialism).

Fernando Castro R. es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador de las revistas Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magaziney Spot.

Fernando Castro R. es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador de las revistas Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magaziney Spot.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

ENDNOTES

[1] Literal magazine #4 (Uploaded April 4, 2012) published my essay, “Xul Solar, vanguardista esotérico” which put a great deal more emphasis on the artist’s life and personality. In this essay I have avoided reference to the avant-garde and Surrealism. https://literalmagazine.com/xul-solar-vanguardista-esoterico/

[2] Xul’s acquisition of this German publication is often mentioned in the literature but seldom described in detail. Der Blaue Reiter Almanach (The Blue Rider Almanac) was edited by Kandinsky and Marc and published in early 1912, by Piper, Munich, in an edition of 1100 copies. It contained reproductions of more than 140 artworks, and 14 major articles. A second volume was planned, but the start of World War I prevented it. Instead, a second edition of the original was printed in 1914. On YouTube I have learned about a smaller “deluxe” edition of 50 that included original prints by Kandinsky and Marc. The original edition included: Marc’s essay “Spiritual Treasures” illustrated with children’s drawings, German woodcuts, Chinese paintings, and Picasso’s Woman with Mandolin at the Piano, an article on Cubism by French critic Roger Allard, Arnold Schoenberg’s “The Relationship to the Text” and a facsimile of his song “Herzgewächse,” facsimiles of song settings by Alban Berg and Anton Webern, Thomas de Hartmann’s essay “Anarchy in Music,” an article about Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus: The Poem of Fire, an article by Erwin von Busse on Robert Delauney, illustrated with a print The Window on the City, Macke’s essay “Masks,” Kandinsky’s essay “On the Question of Form,” Kandinsky’s “On Stage Composition,” Kandinsky’s The Yellow Sound. The selection of reproduced images was dominated by primitive, folk, and children’s art, with pieces from the South Pacific and Africa, Japanese drawings, medieval German woodcuts and sculpture, Egyptian puppets, Russian folk art, and Bavarian religious art painted on glass. The five works by Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin were outnumbered by seven from Henri Rousseau and thirteen from child artists.

[3] Gradowczyk, Mario H. Alejandro Xul Solar. Buenos Aires: Ediciones ALBA, 1994

[4] For example, Maria Bernardete Ramos Flores. “When the dragon takes the horse’s place” (2012). https://www.scielo.br/j/rbh/a/dZg4vBnYVNmr6GPWkGbCsrk/?format=pdf&lang=en

[5] It is worth noting that The Plumed Serpent, a 1926 political novel by D.H. Lawrence, was conceived by the author while visiting Mexico in 1923, and its themes reflect his experiences there.

[6] Xul used an array of symbols that he imbued with a mystic significance. His repertoire included stylized human figures, serpents, dragons, trees, birds, angels, celestial bodies, mountains, stairs, masks, pre-Columbian gods, Egyptian figures, flags, numbers, signs, arrows, etc. Some symbols he concocted himself and others he adapted from mystical, mythical and religious iconography (pre-Columbian, Chinese, Indian, cabalistic, tarot, alchemical, zodiacal, the Christian cross, the Buddhist swastika, the star of David).

[7] Ophiuchus, “the Serpent Bearer,” is sometimes called the 13th or forgotten constellation of the Zodiac. That’s because the sun passes in front of Ophiuchus from about November 30 to December 18 each year. And yet no one ever says they’re born when the sun is in Ophiuchus. That is because Ophiuchus is a constellation – not a sign – of the Zodiac.

[8] Languages become extinct when nobody speaks them. Sumerian, Latin, Sanskrit, Coptic, Aramaic (the language Jesus spoke which was once lingua franca in the middle East) are now dead languages. Experts believe that about half of today’s world languages will disappear in fifty years. Alawa, Hawaiian, Potawatomi, Ume Saami, Ainu and a host of other languages are critically endangered. Neo-Criollo cannot be said to have died because, arguably, it was never alive. Esperanto, the language created in 1887 by Polish ophthalmologist Ludovic Lazarus Zamenhof today claims an estimated two million L2 speakers around the world.

[9] The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society devoted to the study and practice of occult Hermeticism and metaphysics, was active in Great Britain during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Known as a magical order, The Golden Dawn became one of the largest single influences on 20th-century Western occultism.

[10] Occupying Paris: The First Survey exhibition of Latin American Art by Michelle Greet. “A recurring motif in Xul Solar’s paintings, the snake, may signify various religious traditions such as the Judeo-Christian creation myth or the Toltec legend of the feathered serpent, since Xul Solar sought to reveal universal truths by drawing parallels between religious, linguistic and artistic traditions. As one of the most progressive and experimental artists in the exhibition, Xul Solar seems to have been overlooked or misunderstood completely by critics, with one dismissing him as a ‘rather false’ cubist (Cogniat 1924: 436), and the other essentially equating his work with that of Pettoruti (Sawyer 1924: 4).” https://www.academia.edu/8808925/Occupying_Paris_The_First_Survey_Exhibition_of_Latin_American_Art

[11] The original Spanish version of Xul’s self-description is: “…pintor, escribidor, y pocas cosas más, duodecimal y ‘catrólico’ (ca–cabalista, tro –astrólogo, li –liberal, co–coísta o cooperador). Recreador, no inventor, y campeón mundial de un panajedrez y otros serios juegos que casi nadie juega, padre de una panlengua que quiere ser perfecta y casi nadie habla; y padrino de otra lengua vulgar sin vulgo, autor de grafías plastiútiles que casi nadie lee, exégeta de doce más una total religiones y filosofías que casi nadie escucha”.

Posted: December 3, 2022 at 10:58 pm