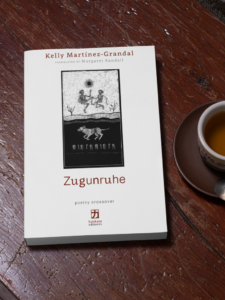

Zugunruhe

George Franklin

Translated by Margaret Randall

Kelly Martínez-Grandal speaks both for others and for herself. It means that when she writes there are two selves speaking, just as kings were once thought to have two bodies, a symbolic body that represents a nation and doesn’t die and a human body, susceptible to love, follies, accidents, age, and death. This is not the same thing as being a “political poet.” The political poet often represents a program or an agenda. The poet of doubleness speaks from who she is. She, like the king, is born into the role. It can’t be sought or assumed. This poet also pays a heavy toll for her duality. The pain she feels is both her own and the pain of her family, her friends, the people she grew up with or saw on the street or the beach, the faces, and even the landscapes, that populate her memory. But, when she writes, her human voice becomes, at the same time, the voice of those like her who have lost their country and sought another.

The title of Kelly Martínez-Grandal’s book is Zugunruhe, a German word that refers to the anxiety animals feel before they migrate, the physical restlessness they experience that drives them to leave, a foretelling of an unknown ill that will descend if they stay. Martínez asks the question in an introductory note, “Do we migrate if something in us is not threatened with Death?” The question, for a poet of two bodies, is more than rhetorical. Martínez’s family left Cuba for Venezuela when she was still in her teens, only to leave Venezuela twenty years later. Even though she was the daughter of important photographers and her home culture was cosmopolitan, this did not protect her from the pain and rejection of immigration. While the absence of community and recognition, however, deprived her of one identity, it gave her a new, mythic identity. She tells us in “Against Goliath”: “You were somebody in your country but here you are nobody. / Nobody / the blindness of Cyclops, / rage of Poseidon, / Circe the witch.”

One of the great strengths of Zugunruhe is the way it embraces myth to find that new identity, an identity that has many voices. This is because the story is not just the story one person, but of many people. In “Nostos” (meaning a homeward journey), the fragmented voices of Odysseus, Circe, Calypso, Sirens, and Penelope are juxtaposed to make it clear that they all take part in this nostos. Martínez-Grandal cannily ends the poem with the line, “Tomorrow I will gather the fragments of my Kingdom,” echoing a line from that master of juxtaposition, T.S. Eliot, in the last stanza of “The Waste Land, “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.”

I don’t want to give the impression that Martínez-Grandal is an icy modernist avoiding the first-person pronoun. A favorite poem in the collection is “Rajatabla Republic,” which recalls “from Miami” her twenties in Venezuela, her friends from that time, dancing and drinking, then going their separate ways, scattered in exile to different continents, as lost as Odysseus ever was. Was there a Rajatabla Bar on Ithaka? Certainly, Martínez-Grandal feels the loss as keenly as that captain did. She writes:

Rajatabla Bar, in your womb I kissed,

took clandestine lovers,

nibbled rabid

on the flesh of my shames.

I left

with all the rage of my twenties.

In your womb we defied God,

only to be expelled, wanderers

children of a faded,

mutilated republic.

Even though the republic she left was mutilated, the poet has no illusions about the republic where she arrived next. The job of the poet is to bear witness not only to executions and deprivation but also to the ironic drudgery of ordinary life. In “Occupational Hazard” she tells us,

To be a poet is to serve the word,

to set its table. If its thirsty,

a lemonade beneath a palm tree,

an Egyptian fan.

But poets also iron, wash clothes,

clean their cat’s poo

and curse or bless their fates.

They have the bad habit of getting it right.

A wonderful aspect of Zugunruhe is the author’s rejection of kitsch and her recognition that it can be found in so many places. Socialist kitsch has been part of the general conversation since Milan Kundera described it so aptly in The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Martínez-Grandal’s allergy to kitsch, like Kundera’s, was likely developed by the obligatory acts of obeisance (e.g., attending parades) she witnessed in Cuba and Venezuela. She feels more than a little anger when she is expected to be one of those happy workers marching off to a glorious tomorrow. From “In Between”:

I never knew what to do on the marches,

I am stunned as I look at the flags.

So excuse me, Eminences, all of you

my meager talent for forging

the new man and his heroes.

My suspicious

tendency

toward the complex, the abyss.

Joseph Brodsky once observed that the reason why authoritarian regimes imprison poets is because poetry by its nature avoids cliché, and dictatorships require their subjects to think in cliché. It’s essential to maintaining power. Martínez-Grandal’s poems are a frontal attach on that kind of assembly-line thinking. Moreover, Zugunruhe take the risks that poetry should take. Martínez-Grandal is able to enter into the experiences of other immigrants, such as Haitians in “Boat People.” She accomplishes this, not by denying racism (which would only lead back to the kitsch she studiously avoids) but by referencing it openly:

— Don’t hang out with Haitians— they told me—

………….Don’t work with Haitians But a Haitian nurse

……………….cradles my father in the lopítal,

helps him die.

It is also a mark of Martínez-Grandal’s understanding of the world that she does not fool herself or the reader about what poetry cannot accomplish. Contra early Neruda, she writes in “Carol” that “even if I write the saddest poems / they won’t heal the world’s wound.” The loss of a country is not cured by the acquisition of a new one either. In the US, after the deprivations of Venezuela, this world of physical richness is not enough either:

But this is a splendid night,

air filled with the scents

of a sizzling stir-fry with onions

and distant jazz comes through the window.

Somewhere people are happy

and Christmas is coming.

If we are far away from home

these lines won’t fix any of it.

The poet who does not lie writes from a position of uncertainty. What can she believe in except her own affections? The supposed good is often mixed with the nauseatingly evil, the world overwhelmingly imperfect. But, she is able to trust, albeit with caution, that which she loves. The climax of Zugunruhe is Martinez-Grandal’s “Jack Kerouac Didn’t Lie to Me,” a road poem that begins with the declaration: “Kerouac’s country no longer exists.” She describes all the ways the America she encounters now does not live up to the myth of On the Road. The country he wrote about “is missing, maybe we should put a / sign up in Walmart: Make America Exist Again.” She does not flinch from categorizing the ugliness and injustice:

except her own affections? The supposed good is often mixed with the nauseatingly evil, the world overwhelmingly imperfect. But, she is able to trust, albeit with caution, that which she loves. The climax of Zugunruhe is Martinez-Grandal’s “Jack Kerouac Didn’t Lie to Me,” a road poem that begins with the declaration: “Kerouac’s country no longer exists.” She describes all the ways the America she encounters now does not live up to the myth of On the Road. The country he wrote about “is missing, maybe we should put a / sign up in Walmart: Make America Exist Again.” She does not flinch from categorizing the ugliness and injustice:

Then I turn on the news and here is a cop who killed a black man. Fuck the pretty sign on the buses, dedicated to Rosa Parks. Here are the Mexicans, “the Pedros and Panchos of stupid civilized American lore”, accused of raping; the elderly, useless to everyone. Native American women are not counted on the lists of missing persons. They’re not even on the bulletin board at Walmart. This is the wheel of hate.

What saves Martinez-Grandal here is not a relinquishing of her skepticism but the Whitmanesque landscape that she witnesses. It becomes a final moment of transcendence for her, as it was for Kerouac:

The highways aren’t the same, they are full of speeding cars; no one cares about anyone.

But the Hudson is still there with giant chimneys shrouded in mist, in the smoke they blow over Manhattan and a farmer is harvesting grain in Oklahoma. Today the evening star will descend upon the prairie.

Kerouac didn’t lie to me.

I have been describing Zugunruhe as though it were a book written in English. This is deliberate, even if a bit deceiving. Apologies. It is a dual-language edition, the Spanish on the left and the English of translator Margaret Randall on the right. However, Margaret Randall is an old friend of Martinez-Grandal, one who has known her since infancy, and they worked closely together to make Zugunruhe as native to American English as possible. The translation deserves to be taken not as an approximation of a Spanish text but as a poem in its own right. There is also a sympathy between poet and translator because Randall’s life of political exile reflects Zugunruhe as well. When Randall returned to the United States after spending twenty-three years in Latin America, the government of the United States attempted, unsuccessfully, to deport her because of the political positions she had taken in her writing. Both poet and translator share an understanding of immigration and of loss.

©Literal Publishing

Posted: March 23, 2021 at 8:26 pm