Mercedes Pardo

Fernando Castro R

“Upon seeing her, I felt that desire to live which is reborn in us whenever we become

conscious of beauty and of happiness.”

Marcel Proust, Within a Budding Grove

Mercedes Pardo [1921–2005, Venezuela]. Untitled, 1987.

Acrylic on canvas. 54 ¾ x 54 ¾ in. (139 x 139 cm.)

In the voluminous book, Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century, curator Rina Carvajal in her essay focused in Venezuelan artists dedicates a few lines to the work of Mercedes Pardo, “In her paintings, which are a dense combination of moods, tensions and chromatic harmonies, colours become, above all, energy and space.” Although half of Carvajal’s adjectives can only be understood metaphorically, they set a course for reflection about Pardo’s mature work.

Mercedes Pardo (1921-2004) was born in Venezuela. As a child she studied painting with Danish professor Ingeborg Fostberg, and at age thirteen, she began taking courses at the Academia de Bellas Artes, which she completed in 1944. The following year, Pardo married Marco Bontá, a Chilean stained-glass and mural painting professor. She went to Chile with him and attended the Escuela de Bellas Artes de Santiago until 1947 —when she had her first solo show at Sala del Pacífico. She divorced Bontá shortly thereafter and moved back to Venezuela.

In 1949, the Venezuelan government awarded Pardo a fellowship to attend the École du Louvre in Paris, where she studied art history under Etienne Coché de la Ferté and Jean Cassou. She also took painting lessons at the atelier of André Lhote but their relationship soured on account of artistic discrepancies. During this Parisian sojourn, she produced collages and her first abstract works. In 1951, she married Venezuelan artist Alejandro Otero in London. The couple returned to Venezuela in 1952, and they participated in the celebrated Primera Muestra Internacional de Arte Abstracto (Galería Cuatro Muros, Caracas). It was in this decade that abstract art began to gain ground in Venezuela as a climate of renewal for both artistic production and education was promoted by the Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV). Pardo produced abstract pieces in the Informalist vein like Composición implícita, 1959 and Sin título, 1969.

Given that abstract art has been a major ingredient of 20th century art, and has become part of the “art establishment” in the 21st, it is hard to fathom how difficult it was for abstract artists to gain acceptance of their work. Even in the culturally sophisticated city of Paris of the 1950s and 1960s, both conservative and leftist intellectuals resisted the advent of non-referential art. María Fernanda Palacios, one of Pardo’s most important commentators, points out, “To choose abstractionism was like adhering to a heresy, to an unpopular and cursed school, to submit to a series of threats and attacks, and to get involved in an endless sequel of justifications.” Palacios adds, “from Les Lettres Françaises, Louis Aragon and other renowned leftists condemned the decadence and escapism of abstract art.” Palacios points to the irony that, “While in the United States abstractionism was from the very beginning an instrument of protest that the left launched against the bad taste and puritanism of the bourgeoisie, in our countries abstract painters were branded traitors to their countries and the revolution.” Hence, in addition to confronting the skepticism of the general public with regard to an art that did not propose a “window” to the world but rather the window itself, abstract artists had to face an ideological opposition from whom their art was “reactionary.”

In 1960, Pardo once again moved to Paris. There she painted abstract watercolors like Cantabile, 1961, characterized by gestural spontaneous brushstrokes, drips, and semi-random blotches over a white pictorial space. Pierre Volboudt, a French art critic, who saw the works, described them as “Poética de lo Instantáneo” (poetics of the instantaneous). The aesthetic of these Parisian untitled Pardo watercolors is not unlike that of the works which Cy Twombly, the quintessential gestural painter, was doing in Rome just about the same time.

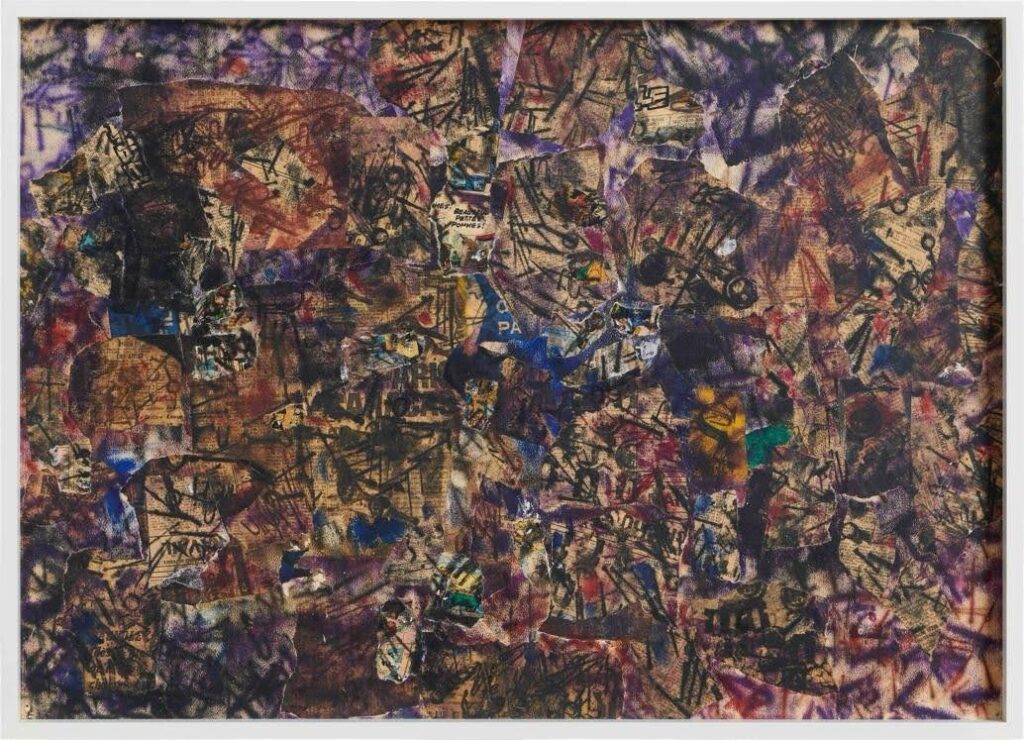

Between 1964 and 1966, Pardo produced intricate collages of newspaper and magazine clippings mounted on wood and Masonite whose exceptional complexity contrasts sharply with the simplicity of her gestural watercolors. She was forty-four when she did the collages Inútil mecánica, 1965, and El Jardín de las Delicias, 1965 —the allusion to Hieronymus Bosch’s masterpiece is due perhaps to the iconographic density of the work and its cryptic nature.

Mercedes Pardo [1921–2005, Venezuela]. Untitled, 1963. Collage on Masonite.

20 13/16 x 29 1/8 in. (53 x 74 cm.)

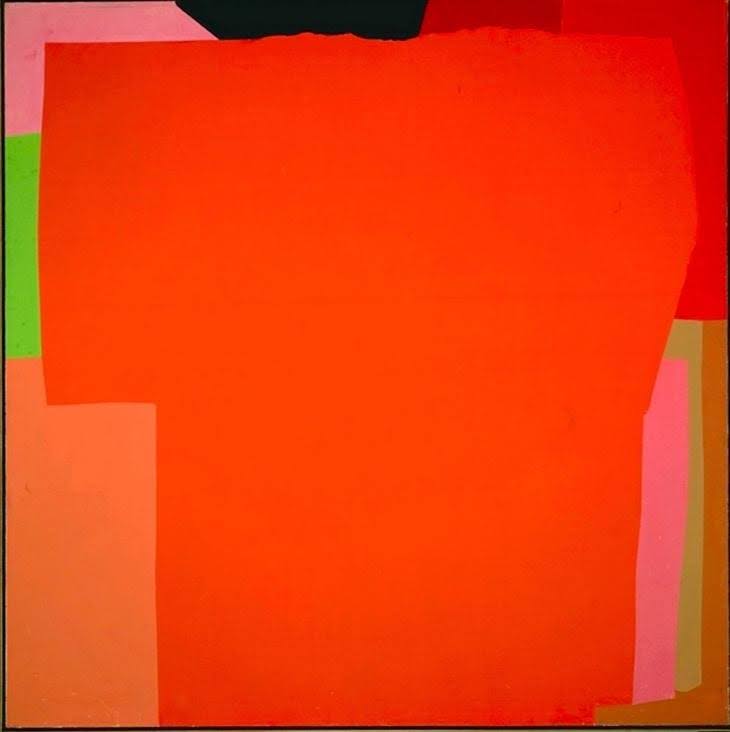

The forging of Pardo’s mature style in the late 1960s surfaced simultaneously with her adoption of a new medium: acrylic paint —faster drying and more color-intense than oil paint. In the official taxonomy of abstract art the denomination of her mature work became: genus color field, species geometric, hard-edge variety.

If we assume that Tú, 1969, a mostly red picture, was her first acrylic painting, it was also seminal, like Les demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907 was for Picasso’s Cubist period. A large red color field occupies most of the canvas and the “formal hard-edge action” takes place mostly near the perimeter, a strategy vaguely reminiscent of Clyfford Still’s 1950_W and John Hoyland’s 17-3-69. However, this “border” strategy is not the only one Pardo explored during her mature period. Usually her works are more buoyant, compelling and unique when the vast expanses of color are interrupted with narrow strips of contrasting colors and forms. Only when these interruptions occur, does it seem like one plane sits on top of a different pictorial plane; otherwise, the shapes appear adjacent, rather than super-imposed.

Pardo seems to have discovered her forte in the transitions from one rectangle to another rectangle of a different color; and in the mixing of primary colors with subtle tertiary hues, not because she underwent some kind of chromatic epiphany, but because it is obvious in her mature work that a great deal of testing and experimentation has taken place before the execution of the works. Whether conjugating shapes that are occasionally not even rectangular, or alternating contrasting or subtly different hues, Pardo is second to none.

Tú, 1969. Acrylic paint on canvas.

What makes Pardo’s mature works so appealing? Palacios herself, has attempted to explain it by a musical analogy, euphonic chords and rhythm included. One assumes that the gist of such an interpretation is to establish a musical model from a painting’s elements and their relationships. However, no matter how symphonic the analogy gets, it falls short from establishing such a model and answering the question. As far as we know, besides giving some of her works musical titles, Pardo has never claimed to possess synesthesia: i.e., that she sees certain musical chords as colors; or that she hears certain colors as musical notes. Nonetheless, there is one musical quality that may have an intuitive counterpart in her work: harmony. If we take the dictionary definition of the term, then dissonance is its opposite, and analogously, dissonant is what Pardo’s works are not.

Remember that we are discussing abstract, color field, hard edge, geometric works whose semantic reach may not be other than themselves. Pardo does not use a mathematical formula to generate works, as arguably might a Mondrian or Albers; instead, she searches intuitively. Although to find her paintings beautiful may be a natural reaction, reducing her works to “beauty” is probably conceptually misguided because she does not follow a canon. What is needed is a concept of beauty more generous than a canonical one, yet not so ample as to be meaningless. As Arthur Danto once wrote, “People have to be brought to understand the work, and the way in which it is actually beautiful.” Perhaps as a harmony of shapes and colors, as Carvajal suggested above with the phrase “tensions and chromatic harmonies”? Pardo’s mature works do show a penchant for harmony and balance that are achieved in specific ways in particular works. When the works are spare, she balances differently than when they are well populated with shapes and colors. Her works reflect an uncanny ability to combine colors harmonically. These characteristics of her works may be the reason why many viewers react to the works citing beauty. Afterall, harmony does feature in more than one theory of beauty as an epiphenomenon of “things that go together well.”

Mercedes Pardo [1921 – 2005, Venezuela] Movimiento íntimo, 1983

Acrylic on canvas. 47 7/32 x 47 7/32 in. (119.9 x 119.9 cm.)

An unexplored theme in Pardo’s oeuvre are her titles. Pardo’s practice of titling some works and not titling others goes back to the early 1950s. Assigning titles to her works does not in any way pick out a unique denotation although it may suggest an interpretation. Otra version de la noche, 1978 (another version of the night) has hues that one might see at night; but one might also see them in things other than the night. At best, the title of that work suggests a poetic interpretation of the work –as would a Rorschach card– but once again, we cannot lose sight of the fact stated above: “we are discussing abstract, color field, hard edge, geometric works whose semantic reach may not be other than themselves.” Needless to say, titles help in talking about a work. It is easier to talk about Insistencia del óxido, 1978 (the insistence of rust) than deal with the ambiguity of many works named “Untitled,1979.”

Pardo’s series of “tributes” or “homages” to different artists are no different. Looking at Homenaje a Fra Angelico, 1984, a keen observer might say, “it bears the colors Fra Angelico used in his paintings.” Could be, but her Homenaje a Miró, 1985 has colors that Miró used, and some he did not use, and the sum-total of Pardo’s work does not bring the Catalonian painter’s oeuvre to mind. This is not a failing on Pardo’s part but a misconception of what her project is all about; namely, a construction of what the works of these artists do to her. Apparently, Pardo made these homages when she was undergoing a particular difficult time in her life. It is no wonder then that her Homenaje a Georges Braque, 1985 should be mostly muddy brown and dark, with only small patches of blue and red.

Whatever her mental states may have been from the moment she painted Tú, 1969 to the time she produced Untitled, 1987, or one of her last acrylic paintings, Horizontes lejanos, 2004 (faraway horizons), Pardo’s work is joyous because her palette is predominantly vivid. Even when she does use muted and even dark colors, as in La Ventana, 1979 (the window) or Giulima, 1988, the harmony and rhythm of her compositions still elicits the kind of contagious joie de vivre to which Marcel Proust alluded.

Houston, Texas

Fernando Castro es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador

Fernando Castro es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: November 20, 2024 at 10:40 pm