Ojo-Hoja, New Artworks by Juan Iván González de León

Tanya Huntington

Art serves no real purpose, or so we are told. That is why it must endeavor to be seductive. Irresistible, even. And yet there is always a distance, a disbelief lodged between ourselves and the myriad forms mimesis takes. Thus, by looking, we may leap without fear of drowning –unless like Narcissus, we rashly forget to look away again.

That same sense of incredulity from which we derive aesthetic pleasure may morph into frustration and anger if we find art to be poorly executed, unfathomable, or offensive. Works that have caused such a reaction may later become turning points and treasured as masterpieces, of course. Even insults like “impressionism” or “cubism” have been known to become canonical descriptions not long after they were hurled by critics. Which may explain why there are artists who have become addicted to controversy to such an extent that their careers seem to be fueled solely by public outrage. The general idea behind pushing society’s buttons is, of course, to inspire reflection and change. But alas, the line has now been blurred between pushing buttons and attaining celebrity status: contemporary art has jumped Damien Hirst’s shark.

There are doubts lurking predatorily beneath the surface of an artist’s need to launch one succès de scandale after another, as if in a succession of flares notifying us of some terrible accident and the accompanying wreckage, that merit our consideration: if art serves no real purpose, why bother? Has art been reduced to endeavoring to remain on the tip of everyone’s tongue and in the feed of everyone’s social networks? And just how can art accomplish this, anyway?

Apparently, recreating dioramas from the natural history museum won’t cut it anymore. The two most notorious works on the Mexican art scene this season revolve around fashioning a diamond ring out of the ashes of a great (and suitably deceased) architect at one end of the spectrum, and recreating an entire convenience store at the other. As an inevitable consequence of the dehumanization suggested by Marx, restated by Ortega y Gassett, and decisively cemented by Adorno, human remains or junk food products are painstakingly being rebranded as luxury items in order to pillory (and profit from) what Noam Chomsky has called our “created wants.” Here is where we stand.

Or is it? Perhaps there is some other art being made beyond the created wants that target a certain income bracket. In fact, such manifestations of art-as-clickbait may be deafening, blinding, and silencing our ability to detect other movements, other forms of creation that continue to quietly evolve beneath all the digital sound and fury.

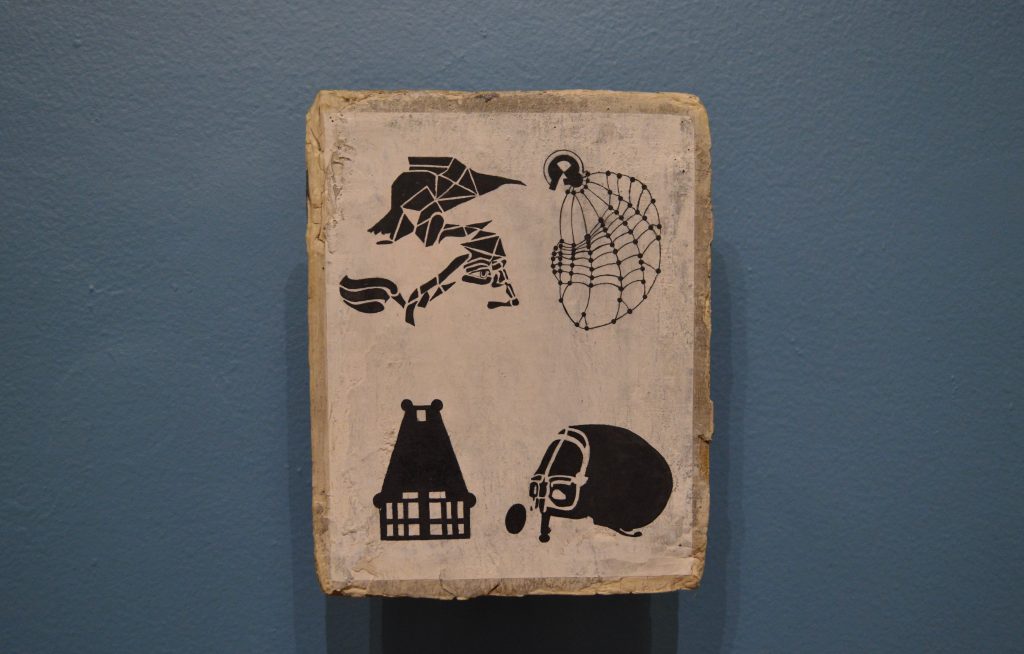

Apéndice I .2012. Motivos

Mixta. 25 x 19 cm.

I have believed for some time that conceptual art, like so many aspects of our world today, masquerades as something new while actually representing a rather conservative continuance of ideas spawned by the Industrial Revolution, indulging in an appetite for classification that governed scientific pursuits at the time. Today, the classifiers –who far from being avant-garde, are traditionalists in their neurotic rehashing of Duchamp– seem to have gained the upper hand with their cabinets of hoarded specimens on private or public display, in archives or on fake store shelves. However, I believe another lengthy endeavor is being developed in tandem: that of exploration. Explorer artists, somewhere beyond the headlines, are registering their own exacting attempts to delve deeper into the unknown through their work as they steadily form an alternative branch on a timetable different than, or rather, indifferent to that of the viral world.

Such was the impression I had while viewing the Ojo-Hoja exhibition of recent works by Juan Iván González de León at the Museo de la Ciudad de México. At times, the point of departure of this explorer artist is the same as that of his classifier contemporaries: the confluence between art and advertising that Warhol became so obsessed with, for example. But what happens when Warhol is taken in another direction? Traces of advertising remain in González de León’s imagery, but they form imprints rather than parameters, clouded by nostalgia as though he were already imagining a post-hyper-consumerist reality. His realm is not that of the visual orgy of excesses that surrounds us, but rather a carefully crafted psychological reality that creates patterns out of dark matter, metabolizing a six-pack of Indio beer on equal quantic footing with the Venus of Willendorf in order to spawn bird-men that, against the grain of our notorious anthropocentrism, are rather more like men impossibly morphing into birds in a desperate search for the unknown.

This artistic process of morphological transmigration, as the artist refers to it, is more akin to biological evolution than to dissection. The works are permeated by a sense of abandonment and doubt that intensifies, rather than lessening, the viewer’s experience, far from the lingering post-mortem sensation of diagnostic certainty that trending-topic art tends to leave in its wake.

On a final note: unlike works flattered by digital reproduction that tend to be a disappointment when one actually stands before them, there are subtle textures and qualities in the Ojo-Hoja series that ought to be experienced first-hand. The delicate sheens and scribbled chalk-like areas found in sections of the series present an opportunity for all of us to go back to the drawing board. As if González de León were suggesting that there is, perhaps, a purpose to art after all.

*Images by Tanya Huntington

Tanya Huntington is the author of Martín Luis Guzmán: Entre el águila y la serpiente, A Dozen Sonnets for Different Lovers, and Return. She is Managing Editor of Literal. Her Twitter is @Tanya Huntington

Tanya Huntington is the author of Martín Luis Guzmán: Entre el águila y la serpiente, A Dozen Sonnets for Different Lovers, and Return. She is Managing Editor of Literal. Her Twitter is @Tanya Huntington

Posted: May 2, 2017 at 8:09 pm