Strawberry Fields

Campo de fresas

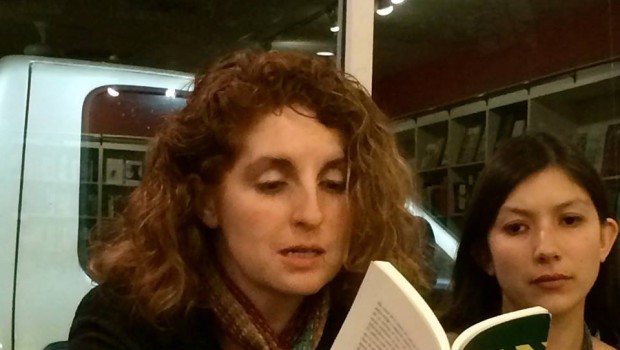

Liliana V. Blum

English translation by Michael Parker-Stainback

The night my father was dying in the hospital, I was cleaning a cat litter box. At least I like thinking that at the very moment his heart ceased beating, I was picking up feline turd without even giving him a thought. That night I came out of my Group Sociology class, where we studied the Oneidas, the Amish and the Manson Family. To avoid any conversation on public transportation, I read some pages of a worn edition of the Bugliosi paperback on my way to Pepita’s house. I let myself in with my key, put my backpack on the floor, and carried the grocery bag to the kitchen. I didn’t say anything, because she would often nod off and got so startled at any kind of noise, that I thought she’d have a heart attack one of these days. I found the living room dark, lit only by intermittent TV flashes. The eight o’clock telenovela had barely begun; my time to show up for work.

This work taking care of the old woman wasn’t bad–not bad at all. Her children, busy with their own lives, hired me to visit her each day. I was to feed the five cats that came and went freely through the kitchen window, make sure they food and water, clean the litter box and do some shopping for the old lady who in fact was quite independent and just needed help changing a light bulb, moving something heavy or threading a needle. I suppose I gave off the impression of being a good girl, patient and a good housekeeper, who wouldn’t strangle their mother with the iron cord and then would run off with her senior-citizen discount card, her savings in the metal box above the piano, the autographed photo of John Paul II and the figure of the Sacred Heart that appears to be burning to anyone who comes into the house. For me the job was some mad money that let me spend without having to worry too much about indulgences. After all, I had my college scholarship, and my mother’s guilt money–she insisted it was her duty to make sure I got a good education without hardships. But taking care of Pepita also had the side effect of making me an object of elegies from strangers and acquaintances alike, who praised me for my charity. Working for a little old lady made me a repository of virtues in the eyes of others and on some days that’s something you appreciate as much as a good foot massage.

When Pepita heard the cats meowing because I had come in, she pulled herself up from the sofa, with some difficulty, and turned on the light. The usual thing was for her to greet me with a “goodnight, my dear” before offering me a pastry and an instant coffee “au lait,” in addition to thanking me for my punctuality. It’s not healthy for a young girl like you to be so skinny, she says. My answer is to remind her I’m a size nine, eat a ginger cookie, and wash it down with a glass of milk. Then she tends to begin her diatribe against people who get everywhere late and the decline of “these kids today.” But that night the expression I saw in Pepita’s face was the same as when Milo, the orange tabby, got out and never came back.

Is something wrong?, I asked, as I opened a can of tuna.

Pepita has short, gray hair and she tends to wear it in a juvenile style, with two flowered barrettes. I always avoid looking at her because I don’t like to think of her as this pathetic being, so I focused on mixing the tuna with the dry cat food.

They just put your father in the hospital. He’s in really bad shape.

I put the plate down on the floor and the cats gathered around it with their tails in the air like the undulating rays of some sun. My mother had insisted I leave a phone number where they could find me. It’s not an office, I told her. And though she suffers from a compulsion to know exactly where I am, day and night, she denies what happened right under her roof over the course of so many nights. They weren’t methodically arranged sexual relations, like those of the Oneidas, but they were tolerated anyway; not with a previously agreed to list, but with eyes closed. In the end I gave her Pepita’s number, just to get her to shut up. She had always been absent from my life and I thought things were going to stay that way. I didn’t think she was going to call me.

Thanks for letting me know, I said, and I sat at the table with my purchases notebook and a ballpoint pen. I clenched it until my fingers turned red. What was she going to need me to bring her tomorrow?

Your father is in the hospital. You don’t have to come in, she said, touching my forearm.

It’s strange to think that he’s suffering, I said. I could see that something dark and problematic was concentrating in her eyes, but that didn’t keep me from going on. You always think the roles are fixed, you know? Especially when they’ve been that way for years. I couldn’t help looking at the floor as I said it. But then I looked right at her and concluded: So the news you’ve just given me is a real revolution for me, Doña Pepita.

I doubt she could have understood me. Maybe the only thing she was able to get was the tone of my voice and my reaction, which were not those of a good little girl. I looked at the purple caterpillars that were her veins, her spotted skin. Her husband had been dead for more than ten years, but Pepita still wore her wedding ring on her wrinkled finger. Witches’ hands were like that in my children’s books.

She stood up and went to the refrigerator. The cats meandered around her legs; they loved to get in close and sniff the leftovers in their containers. Or maybe they did it to cool off. She stopped before opening the refrigerator and pulling out a vial of insulin. She waited for the cats to get out of the way and then shut the door. She sat down again next to me. She rolled up her sleeve and exposed the dry, flaccid skin on her arm. I got the syringe ready. The needle penetrated easily and I pushed in the plunger too forcefully. She let out a small groan and readjusted her blouse.

Doña Pepita, I promised your children I would never miss work. So go ahead and tell me what you need from the store tomorrow.

But honey, honey, honey…

Her pale, wrinkled face was all that had survived from a beauty that had long ago disappeared. She half closed her eyes, shaking her head from side to side, and then she made a movement with her mouth to adjust her dentures. When I was a girl I thought that before they went to bed, my grandparents would drink the contents of the glass on the nightstand where their teeth were. I also believed that someone was going to come rescue me when my father would come in and sit on the edge of my bed. Childhood is a sea of misunderstanding.

Did I tell you that members of the Manson family would write the word pig on the walls, in their victims’ blood? I asked her in the same tone that you might pass on some family gossip.

Pepita stood up silently and sent me a reproachful look before leaving the kitchen. Maybe the years do end up producing a little wisdom in people, if only as a side effect. I heard her murmur something about my descent to that circle of Hell where ungrateful children go to roast. She turned on the television and feigned interest in her telenovela. Incredibly, it began to hail not long after. For a moment I just sat there, looking out the window, hypnotized, as all those white projectiles struck everything that could be struck outside.

I made a small inventory of what was in the refrigerator and the pantry to make a provisional list. It was almost always the same thing, unless Pepita wanted something special, like a votive, or cough syrup, or some miracle tea. I brought her snack on a tray, but she didn’t indicate she’d seen it, and kept her eyes on the screen, her neck stiff, and her lips tightly closed. If she was under the impression I was going to fall for her blackmail–sit down and negotiate her eating in exchange for visiting my father–she was quite mistaken. At that point I wouldn’t have cared less if she decided never to eat again.

I headed to the bathroom and began to clean out the litter box. The cats watched me from a certain distance, nervous. I heard the telephone ring in the bedroom. I walked slowly hoping it would ring several times and whoever it was would give up and hang up. But the ringing never let up. I thought that Pepita would shout at me to hurry up and answer, but she stuck to the silent treatment. I picked up the receiver: it was Moira. She didn’t say hello or ask me how I was. The first thing she told me was that my mother had called our apartment to give me the bad news.

What, did she break a nail?

No, your father died.

After that, my friend didn’t say anything. I don’t blame her. The normal thing in serious conversation would be for me to say something, but I stayed quiet, listening to the blood circulate though my body, the sound of my throat as it choked down some saliva; life was still within me. I don’t know how many times I’d wanted to hear the words that Moira had just said.

Are you there, Noelia?

Yes.

I just don’t know what to say to you, she uttered by way of excuse.

I have to get rid of a bag full of cat shit, so I’ll see you later.

I hung up softly to go back to the bathroom and finish up with the cat box. Its smell began to make me nauseous: all my senses were heightened and that wasn’t necessarily bad. The cat thing offended my nose, but my skin perceived the brush of my clothing in a way that was almost erotic and my ears marveled at the sound of the birds outside, returning to their nests for the night. The physiological part of me celebrated the miracle of being alive. But I wasn’t going to get a present for it, not even a hug: when I started to go out, I ran into Pepita, standing right in the door jamb, with her hands crossed over her breast, blocking my way. Judging by the look on her face, it was clear she’d overheard my half of the conversation.

She scanned me from head to toe, pausing between my face and my legs, as if she were going to find the reasons for my ingratitude to my father in that part of my body. But I wasn’t going to open up to some cat lady who liked high-fiber cereals. When I told Mom, she said she didn’t have any time for my foolishness. No father sits on the edge of his daughter’s bed to masturbate himself with her hand while she sleeps. That was a lie that could get me sent to the insane asylum if I kept repeating it, she warned me. Then she ran off to the beauty parlor. No one had ever seen her roots show up and that day wasn’t going to be the first time they did.

On the other hand, with my father there was a first time and there was nothing there to indicate it would be the last. Life happened with its hours and weeks and months; the routine would only end with one or the other’s death, but both he and I continued to exist. Life is brutish and time passes with overwhelming slowness when someone uses your hand to get off. A bovine instinct led me to act normal in front of others, from one day to the next, taking care of the basics like bathing, eating and going to school. When he would jack off with my hand I pretended to be asleep. It never occurred to me to do otherwise. Maybe that’s why he thought it was safe to go further and he began lifting up the sheet as I held my teddy bear between my legs. Of course, that wasn’t the best barrier since he entered me anyway.

I remember his smoker’s breath, in my ear, like this purr that never went away. The minutes got longer, the pain made me shut my eyes tightly and that was when I wished for his death. Or mine–but I never had the courage to kill myself. My fantasy was to die when my parents were traveling, so that when they got back they’d find my body substantially decomposed. The smell would have seeped into the furniture and the only solution would be to get rid of the carpet. A cadaver is not the problem of the person who once inhabited it.

Excuse me, please.

After a second or two, Pepita got out of the way and let me through. I put my backpack on and grabbed the garbage bag to put into the shared cans, on my way out. I didn’t thank her and she didn’t thank me. To her and lots of others, I was nothing more than an ungrateful daughter. The fruit of a society where there were no more values. A woman from a self-centered, superficial generation. My attitude provoked the same repulsion in her that the smell of her telephone–a concentration of her breath rot from over the years–did in me.

I’m going to ask my sons to look for someone else to help me.

I get it.

There was no anger in her eyes, just a sort of caution. Maybe even some hope that the threat of losing my job would make me reform with regard to my father. The old woman’s face formed no particular expression; it remained in the air, tentative and ambiguous. I suppose she felt a fear she extrapolated about if her own children reacted the same way about her death. The poor thing didn’t have a clue.

The cats were rubbing against my legs and meowing like when they are hungry. Now I didn’t have to listen to them. I could go back to breathing without having to worry about their fur. I would not come back to this house that smelled of feline and human piss. I smiled. My entire face contracted into a smile. Then I went out into the night and the noises of darkness surrounded me right away. I tossed out the bag along with the shopping list and I began to walk down the damp sidewalks. The sleet that had piled up in the gutters was melting now. The city looked just as it always did, but today it didn’t leave me feeling empty, as it tended to do. This time it was more like walking through a strawberry field, finally, with my heart forming a power fist for peace.

• Fragment of Don’t Pass Me By (Literal Publishing, 2014)

La noche en que mi padre moría en el hospital, yo limpiaba el arenero de los gatos. Al menos me gusta imaginar que en el preciso momento en que su corazón dejó de latir, yo levantaba la mierda gatuna sin dedicarle siquiera un pensamiento. Aquella noche salí de mi clase de Sociología de Grupos, en donde estudiábamos a los Oneida, los Amish, y a la familia Manson. Para evitar conversaciones en el transporte público, leí algunas páginas del maltratado paperback de Bugliosi en el camino a la casa de Pepita. Abrí con mi propia llave, puse mi mochila en el piso, y llevé la bolsa de víveres a la cocina. No dije nada porque con frecuencia ella suele dormitar y se sobresalta tanto con cualquier ruido, que temo que su corazón se detenga en una de ésas. Encontré la sala a oscuras e iluminándose con los brillos intermitentes de la televisión. La novela de las ocho de la noche apenas comenzaba: mi hora de llegada.

Este trabajo de cuidar a la anciana no estaba nada mal. Sus hijos, ocupados con sus propias vidas, me contrataron por visitarla a diario. Era mi deber alimentar a los cinco gatos que transitaban con libertad a través de la ventana de la cocina, asegurarme que tuvieran comida y agua, limpiar el arenero y hacerle las compras a la anciana, que era en realidad muy independiente y sólo requería ayuda para cambiar algún foco fundido, mover un objeto pesado o enhebrar una aguja. Supongo que yo daba la impresión de ser una buena chica, paciente y modosa, que no extrangularía a su madre con el cable de la plancha para luego huir con su tarjeta de descuento de la tercera edad, los ahorros dentro de la cajita metálica arriba del piano, la foto autografiada del Juan Pablo II, y la figura del Sagrado Corazón que parece abrazar a quienquiera que entra a la casa. Para mí, el trabajo era sólo un ingreso extra que me permitía gastar sin poner mucha atención a mis caprichos. Después de todo, tenía la beca de la universidad y el dinero culposo de mamá, que aseguraba que era su obligación cerciorarse de que yo tuviera una buena educación sin pasar penurias. Pero cuidar de Pepita también tenía el efecto secundario de hacerme acreedora a elogios de extraños y de conocidos, que alababan mi caridad. Trabajar para una ancianita me volvía un dechado de virtudes ante los ojos de los demás y en algunos días, eso es algo que se aprecia tanto como un buen masaje de pies.

Cuando Pepita escuchó a los gatos maullar por mi presencia, extrajo su cuerpo del sofá con cierta dificultad y encendió la luz. Lo normal es que me salude con un buenas-noches-mijita antes de ofrecerme pan dulce y nescafé con leche, además de agradecerme mi puntualidad. No es sano que una jovencita como tú esté así de flaca, dice. Mi respuesta es enarbolar mi talla nueve como una excusa, pero siempre termino comiendo un cochinito de jengibre con un vaso de leche al final. Luego ella suele comenzar con su diatriba contra la gente que llega tarde a todos lados, y con la decadencia de la juventud de hoy. Pero esa noche vi en la cara de Pepita aquella misma expresión de cuando Milo, el gato naranja con rayas, salió para no volver.

¿Pasa algo?, dije mientras abría una lata de atún.

Pepita tiene el cabello corto y canoso y por lo regular lo lleva en un peinado infantil, con broches con forma de flores. Siempre evito mirarla porque no me gusta pensar en ella como un ser patético, así que me concentré en mezclar el atún con las croquetas para gatos.

Acaban de internar a tu papá en el hospital. Está muy grave.

Puse el plato en el suelo y los gatos se juntaron alrededor con sus colas en alto como los rayos de un sol ondulante. Mi madre había insistido en que dejara un teléfono donde me pudieran localizar. No es una oficina, le dije. Aunque sufre de una compulsión por saber en dónde me encuentro exactamente a cada hora del día, niega lo que sucedió bajo el techo de su misma casa durante tantas noches. No fueron las relaciones sexuales metódicamente arregladas, como en la comunidad Oneida, pero igual se permitían; no con una lista previamente concertada, sino con los ojos cerrados. Al final terminé dándole el número de Pepita, sólo para dejar de escuchar su voz. Siempre estuvo ausente de mi vida y pensé que seguiría siendo así: no creí que fuera a llamar.

Gracias por avisarme, dije y me senté en la mesa, con la libreta de las compras y un bolígrafo. Lo apreté con fuerza hasta que mis dedos se pusieron rojos. ¿Qué cosas va a necesitar que le traiga mañana?

Tu papá está en el hospital. No tienes que venir, dijo tocándome el antebrazo.

Es raro pensar que está sufriendo, dije. Pude ver que algo oscuro y problemático comenzaba a concentrarse en sus ojos, pero eso no me impidió seguir. Uno siempre piensa en los papeles como inamovibles, ¿sabe? Sobre todo cuando duran muchos años. No pude evitar mirar el suelo al decir esto. Pero luego fijé la miré en ella y terminé: Así que la noticia que me da es una revolución para mí, doña Pepita.

Dudo que pudiera entenderme. Tal vez lo único que podía captar era el tono de mi voz y mi reacción, que no era la de una buena hija. Vi las orugas moradas de sus venas y su piel con manchas. Su esposo lleva más de diez años muerto, pero Pepita conserva la argolla matrimonial en el dedo arrugado. Así eran las manos de las brujas en mis libros infantiles.

Se puso de pie y se dirigió al refrigerador. Los gatos se le enredaron en las piernas: les encantaba meterse y olisquear los recipientes con sobras de guisos. O tal vez lo hacían para refrescarse. Ella se detuvo antes de abrir la puerta y sacar un frasco de insulina. Esperó a que los gatos salieran y cerró. Volvió a sentarse junto a mí. Se levantó la manga dejando al descubierto la piel reseca y flácida de su brazo. Yo preparé la jeringa. La aguja entró fácilmente en su carne y yo apreté el émbolo con demasiada fuerza. Ella dio un pequeño gemido y se acomodó la blusa.

Doña Pepita, le prometí a sus hijos que no faltaría a mi trabajo. Dígame, ¿qué le traigo del súper?

Mija, mija, mija.

Su cara pálida y arrugada era todo lo que quedaba de una belleza que hace mucho se había ido. La anciana entornó los ojos meneando la cabeza de un lado a otro y luego hizo un movimiento con la boca para reajustarse la dentadura. Cuando era niña pensaba que antes de irse a dormir los abuelos se bebían el vaso con dientes sobre el buró. También creía que alguien iba a venir a rescatarme cuando mi padre llegaba a sentarse en la orilla de mi cama. La infancia es un mar de malentendidos.

¿Ya le conté que los miembros de la familia que formó Manson escribían en las paredes la palabra “cerdo” con la sangre de sus víctimas?, le dije con el mismo tono de quien comparte un chisme familiar.

Pepita se puso de pie en silencio y me dedicó una mirada de reproche antes de salir de la cocina. Tal vez los años sí terminan por producir un poco de sabiduría en las personas, si acaso como efecto secundario. La escuché murmurar algo sobre mi descenso hasta la parte del Infierno donde se calcinarán los hijos ingratos. Encendió la televisión y fingió interesarse en su novela. Increíblemente, comenzó a granizar poco después. Por un momento me quedé allí, mirando hipnotizada por la ventana cómo esos misiles blancos golpeaban todo lo golpeable allá afuera.

Realicé un pequeño inventario de los contenidos del refrigerador y de la alacena para hacer una lista provisional. Casi siempre eran las mismas cosas, a menos que Pepita quisiera algo en especial, como una veladora, un jarabe, o algún té milagroso. Le llevé su merienda en una charola, pero no se dio por enterada y siguió mirando la pantalla, el cuello tenso y los labios apretados. Si creía que yo iba a caer en el chantaje e iba a sentarme a negociar su alimentación por una visita a mi padre, estaba muy equivocada. En ese momento no me podría importar menos si ella decidía no volver a comer jamás.

Me dirigí al baño y comencé a limpiar la caja de arena. Los gatos me vigilaban desde cierta distancia, nerviosos. Escuché sonar el teléfono en la recámara. Caminé lentamente, esperando que sonara varias veces y quien sea que fuera, se diera por vencido y colgara. Pero el timbre no cesaba. Pensé que Pepita me gritaría que me apurara a contestar, pero persistió en su afán de mudez. Levanté la bocina: era la voz de Moira. No me saludó ni me preguntó cómo estaba. Lo primero que me dijo fue que mi madre llamó a nuestro departamento para darme la mala noticia.

¿Se le rompió una uña?

No, se murió tu papá.

Después de eso, mi amiga se quedó callada. No la culpo, lo normal en una conversación sería que yo dijera algo, pero permanecí en silencio escuchando la sangre correr dentro de mi cuerpo, el sonido de mi garganta al tragar saliva, la vida que persistía en mí. No sé cuantas veces deseé escuchar las palabras que Moira recién había pronunciado.

¿Sigues allí, Noelia?

Sí.

No sé qué decirte, se excusó.

Tengo que tirar una bolsa llena de caca de gato, te veo luego.

Colgué con suavidad el auricular para ir al baño a terminar de una vez con la caja de arena. Comencé a experimentar náuseas por el olor del arenero: todos mis sentidos estaban exacerbados y eso no era necesariamente malo. Lo de los gatos era ofensivo para mi nariz, pero mi piel percibía de una forma casi erótica el roce de mi ropa y mis oídos se maravillaban por el sonido de los pájaros afuera, retornando a sus nidos para pasar la noche. La parte fisiológica de mi persona celebraba el milagro de estar viva. Pero no iba a recibir ningún regalo ni siquiera un abrazo: cuando iba a salir, encontré a Pepita de pie en el umbral, con las manos cruzadas sobre el pecho, bloqueándome el paso. A juzgar por la expresión en su rostro, era claro que había estado escuchando mi parte de la conversación.

Me miró de arriba abajo con una pausa entre mi cara y mis piernas, como si en esa zona de mi cuerpo se encontrara la razón de la ingratitud hacia mi padre. Pero yo no iba a sincerarme con una amante de los gatos y del cereal alto en fibra. Cuando se lo conté a mamá, ella dijo que no tenía tiempo para mis tonterías. Ningún padre se sienta en la cama de su hija para masturbarse con la mano de ella mientras duerme. Eso era una mentira que me llevaría al manicomio si yo la seguía repitiendo, me advirtió. Luego se fue con el estilista. Nunca nadie le ha visto el cabello creciendo con un color distinto y aquel día no iba a ser la primera vez.

En cambio, con mi padre sí la hubo y no había nada que me indicara que sería la última. La vida se sucedía con sus horas y semanas y sus meses; aquella rutina sólo podía romperse con la muerte de uno de los dos, pero tanto él como yo seguíamos existiendo. La vida es terca y el tiempo pasa con lentitud pasmosa cuando alguien usa tu mano para eyacular. Un instinto bovino me arrastró a actuar de forma normal a la vista de otros, de un día hasta el siguiente, realizando actividades básicas, como bañarme, comer, ir a la escuela. Cuando él se masturbaba con mi mano, yo pretendía dormir. Nunca se me ocurrió hacer otra cosa. A los ocho años, el miedo congela. A lo mejor por eso él creyó que era seguro ir más allá y comenzó a levantar la sábana mientras yo apretaba un osito de peluche entre mis piernas. Desde luego no era la mejor barrera porque él entraba en mí de todas formas.

Recuerdo su respiración de fumador en mi oído como un ronroneo que nunca se iba. Los minutos se alargaban, el dolor me hacía cerrar los ojos con fuerza y era entonces cuando deseaba su muerte. O la mía, pero jamás tuve el valor para suicidarme. Mi fantasía era morirme cuando mis padres estuvieran de viaje, para que encontraran el cuerpo ya bastante descompuesto al llegar. El olor impregnaría los muebles y la única opción sería deshacerse de la alfombra. Un cadáver ya no es asunto del que alguna vez habitó en él.

Permiso, por favor.

Después de unos segundos, Pepita se movió para darme el paso. Me colgué la mochila en la espalda y tomé la bolsa de basura para dejarla en los botes comunales al salir. No le di las gracias ni ella a mí. Para ella y para muchos otros, yo no era más que una hija ingrata. El fruto de una sociedad donde ya no había valores. Una mujer que pertenecía a una generación egoísta y superficial. Mi actitud le provocaba la misma repulsión que a mí el hedor de la bocina del teléfono de su casa, una concentración de su aliento podrido a lo largo de los años.

Le voy a decir a mis hijos que busquen otra persona que me ayude.

Sí.

No había ira en sus ojos, sólo una especie de cautela. Tal vez incluso había una cierta esperanza de que ante la amenaza de perder mi trabajo yo pudiera recapacitar con respecto a mi padre. La cara de la anciana no se asentaba en ninguna expresión, sino que se sostenía como en el aire, tentativamente ambigua. Supongo que sufría un miedo extrapolado de que sus hijos reaccionaran de la misma forma ante su propia muerte. La pobre no tenía idea.

Los gatos se frotaron contra mis piernas y maullaron como cuando tienen hambre. Ya no tendría que oírlos. Podría volver a respirar sin cuidarme de sus pelos. No volvería a esa casa que apestaba a orines felinos y humanos. Sonreí. Todo mi rostro se contrajo en una sonrisa. Luego salí de la casa y el silencio de la oscuridad me envolvió en seguida. Tiré la bolsa de plástico junto con la lista de los víveres, y comencé a caminar por las banquetas húmedas. El granizo acumulado en las orillas ya se estaba derritiendo. La ciudad se veía igual que siempre, pero ese día no me hizo sentirme hueca, como suele hacer. Más bien fue como andar por en un campo de fresas, al fin, con el corazón hecho un puño de paz.

• Fragmento de No me pases de largo (Literal Publishing, 2014)