Sucre Alley

Rosario Sanmiguel

The night does not advance. I open a book and try to populate the hours with unfamiliar characters that softly lead me by the hand through the pages of others’ lives. I fail. It seems the hours are stalled between these shadowy, sterile walls. I light a cigarette, then another; I suppose it takes me between five and ten minutes to finish each one. At my side, a woman spread out on a narrow sofa stops snoring a few seconds but immediately resumes her sonorous breathing.

I walk towards the glass door and spy on the empty street; only a cat crosses quickly, as if not wanting to disturb the peace. The sign on the café in front is off. Two men hurry to finish their drinks while the waiter nods off at the cash register. Without a doubt, he is waiting until they are finished to turn off the lights and enter dreamland, that region which faded away for me days ago.

I return to the sofa just as the woman invades my seat with her outstretched legs. I move toward a group of nurses who talk quietly and ask them for the time. Threethirty. I pass though the half-light of the corridor to reach Room 106. I don’t have to look for the little placard with the number, I know exactly how many paces separate Lucía’s room from the waiting room. She isn’t asleep either. As soon as she notices my outline under the lintel, she murmurs that she’s hot. She asks me for something to drink. I moisten my handkerchief with water from the tap and just barely wet her lips. “Give me water, please.” I don’t hear her plea. I know that her eyes are following me in the darkness of the room. I know that she will remain attentive to the brushing of my steps across the polished tiles. I leave the room so as not to glimpse her green eyes, so as not to see her converted into a battleground where sickness steadily advances. I pass to one side of the sofa where the woman is still sleeping to turn off the little lamp that illuminates her feet.

Once on the street, I hesitate before deciding my course. A few blocks away, the city’s luxurious hotels are celebrating the weekend’s nocturnal festivities. I head indecisively towards Avenida Lincoln. Sweet-smelling women stroll along the streets, make it impossible for me to forget the scent of the boiled sheets that envelop Lucía’s beloved body.

The shadows dissolve under the marquee lights. Night does not exist in this place.

On the riverbank, I hail a taxi to take me to the Centro. The driver wants to talk but I don’t respond to his comments. I’m not interested in his stories—the preppy kid who refused to pay or the tips that the tourists give in dollars. I don’t want to hear about murders or women. We go down Avenida Juárez––filled with commotion, cigarette sellers on the corners, automobiles outside the clubs, denizens of the night. On both sides of the street the glaring signs compete for the attention of the people wandering around, searching for a place to kill time. I get out at Sucre Alley, in front of the door to the Monalisa.

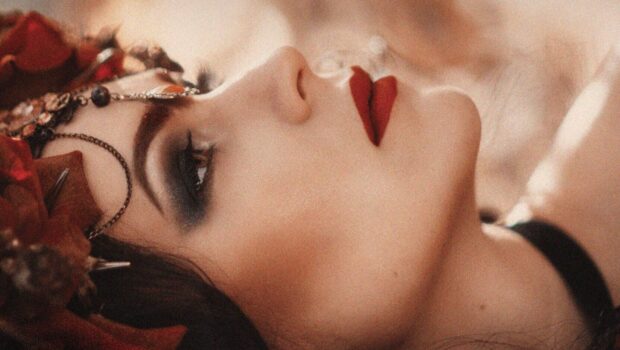

A woman with Chinese eyes dances on the catwalk that divides the hall into two sections.

A group of teenagers scandalously celebrates her gyrations. The rest of the late-night partiers wrap their lips around their bottles and down the last of their beer. I rest my elbows on the bar and watch the woman with Oriental features closely. A beautiful skein of dark hair reaches to her waist, but a repugnant, huge, black mole blots one of her thighs. As the Oriental woman dances, I remember Lucía up on that platform. I see her dancing. I see her slender feet, her svelte ankles, but what also comes to my mind is the enormous suture that now cuts across her stomach. I remember the catheters, tubes and probes that invade her body.

The dirty curtains at the back of the bar open: Rosaura emerges to supervise the establishment. Years before, we saw each other for the last time, when Lucía and I deserted, when we abandoned Rosaura and her world. She comes forward proffering exclamations of joy that leave me indifferent. I exchange a few words with her, unmoved, and discover deep wrinkles in her skin that are accentuated mercilessly each time she breaks out in a roar of laughter. Someone calls out to her from the table furthest away and she obligingly attends to them. I attempt to keep her in my sight despite the low light and the smoke that suffocates the air. With a napkin, I clean the clouded panes of my glasses, and then I too head over to the table. As I move closer my certainty grows: in her face, I see my own. When I come up next to her, I make a sarcastic expression with my mouth.

We’re almost in our fifties, I tell her. Before responding, the matrona erupts in another howl of laughter. And how are things going with the beautiful Lucía? Let her know I’m still saving her place for her. The old woman gets up from the table, chuckling. Her words fall upon me like bags of sand crashing down on my shoulders. I feel the sweat make my clothes stick to my skin and I go out into the street, where the heat lessens a little. While I decide what to do, I look over and over at the facades of the bars clustered on this, the most dismal street of the city. I have the sensation that I’ve fallen into a trap. I didn’t come looking for anything, but despite that, I find the long-hidden picture of an over-the-hill, second-rate cabaret host. To distract myself I light a cigarette that only manages to turn my breath sour.

On my way back, each step I take makes the silence more profound. The houses are darkening. Behind the windows, I imagine bodies captive in sleep. Cats lie in wait for me on the rooftops. The trees are united in one long shadow, epidermis of the night.

In her bed, Lucía is still awake. I leave the room and in the waiting area find the sofa empty. So I lie myself down and await the passage of another night.

Posted: April 12, 2012 at 8:37 pm