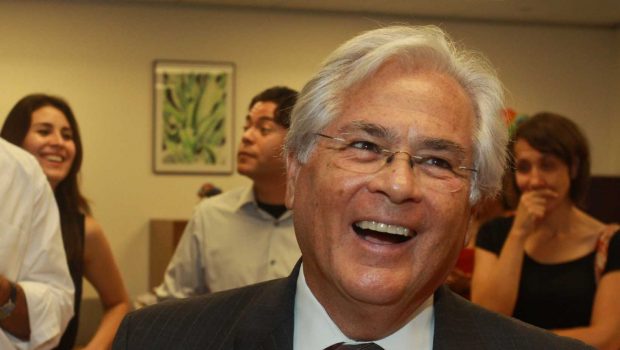

Super Novas: A Conversation with Cuban-American Writer Himilce Novas

Mónica María Parle

One imagines that being part of a prominent literary and intellectual family in the exiled, 1960’s-era, Cuban-American community of New York City would be a heavy mantle to bear, and yet, essayist, poet, and fiction writer Himilce Novas’ talent seems weightless. Her creative forays volley from teaching to radio commentary and from incisive essays to the wonderfully lyrical novels and stories that have won her wide acclaim. Her two novels Mangos, Bananas, and Coconuts (Arte Público Press, 1996; Riverhead/Putnam, 1997) and, more recently, Princess Papaya (Arte Público Press, 2004) have garnered her the acclaim of critics and her peers. Of her newest novel, Isabel Allende said, “Her writing is universal and timeless. Princess Papaya is beautifully rendered, chilling, touching, and haunting.” From the first line, Novas’ storytelling weaves an enthralling spell. The novel follows a Cuban-American family in post-9/11 New York City as they confront the mysteries of their past and the failures and betrayals of their present reality. From a greedy doctor who performs late-term abortions to a young child with extraordinary spiritual powers to a poet who has lost her muse, Novas creates a cast of characters that challenge the reader to reexamine the world in which they live. Ever courageous and unafraid to challenge mainstream thought and writing, I had the opportunity to chat with Himilce about her life and her work.

* * *

M. P.: When you sat down to write Princess Papaya, what came to you first: A character? An image? A scene?

H. N.: One sees (or perhaps I should speak only from my own experience and say “I see,” although it is arguable that there is a common denominator to all writers, and thus when I say “one sees,” I probably mean “I see and I think the writer sees”) a character against the backdrop of a situation, a life unfolding in a particular corner of a world. Then, to that character other characters accrue. These become the “cast” of the story that is being told, hummed, and droned inside me and which I’ll eventually decal onto the written page.

I should clarify that that original character around which the story unfolds is ultimately not necessarily the “main” character in the written story—at least not to the naked eye. She/he is perhaps the heart or vena cava, but the work itself depends on the equipoise, gestalt, synergy, and interplay between the characters, their lives, their compounded fate, and their aggregated substance.

M.P.: One of your characters is Victoria Lobo, who has lost her husband in the events that unfolded on 9/11. Since 9/11 has dominated political and social conversation and thought in the US and abroad for four years, I wonder at the challenge it poses as a subject of fiction. Was there anything you felt you had to represent with regard to survivors? Was there anything that you insisted you would not represent?

H. N.: 9/11 was metaphor and catalyst to depict the violent and unexpected loss of a loved one. It gave me a prism for Victoria Lobo to see her husband’s life immolate before her on the TV screen. I could have equally chosen a different random act, such as a traffic accident or a driveby- shooting along some anonymous highway. But by choosing the plane en route to NY from Boston crashing into the WTC tower, I chose a collective grave, a grave in the collective unconscious, a funeral larger than life that all readers had already attended and considered and mourned. That is, I drew the reader to a familiar ground zero. However, the 9/11 attack itself was not part of the story.

For me, the random act of Francisco’s sudden death and deconstruction was the point—i.e. the seeming senselessness of the accidental victim and the impact it had on the attending characters, particularly Victoria. I guess one thing my choosing 9/11 certainly did not represent was a political message. It was the personal message, the lives lost and the lives shattered as a result of a senseless act that I was after. Of course, politics and the broad flux and efflux of human actions impact the individual, so in that sense politics was the silent presence in the story.

M. P.: Your father, Lino Novas Calvo, is one of the most acclaimed short story and novel writers in Latin America and the Caribbean. Do you see his fingerprint in your own work?

H. N.: We each have our own highly individual voice and I cannot say that his writing directly influenced mine, either stylistically or thematically. Also, I am an American writer writing in English and one cannot underestimate language and cultural point of view when looking at a writer’s work. But my father did teach me a lot about literature and about the craft of writing itself. He also taught me how to read and write by reading me his translations of Faulkner, Joyce, and Hemingway (among many others) before I was 4 years old. Most of all, he taught me that a writer writes.

I also think that his sense of honra and his fairness and his humility and his compassion for those who are unjustly treated and persecuted helped to shape my own view of life and ergo my literary compass. Both he and my mother, Herminia del Portal, were seminal in that sense, as well as in the most fundamental sense. I learned from both and miss them terribly.

M. P.: I’m interested in how language interacts with the stories you’re telling. Obviously, there is the issue of a writer’s facility with language that comes into play, but for someone like you who is bilingual, are there any other conscious decisions that inform you writing in English? Does it change you as an AMERICAN writer?

H. N.: I am actually quatrilingual: English, Spanish, French, and Italian. I have translated works from all four languages (art books, articles, etc) and write and speak all fluently and “natively.” I learned all four at the same time. However, my innermost language is English. That is my ready-think voice, my knee-jerk, and my writer’s pen. I don’t have to think about language when I write. (I do not write in translation, after all!) It thinks me, and you cannot tell the dancer from the dance. As Alexander Pope said about Newton: he lisped in numbers for the numbers came. I am an American writer who writes in English, the same as Emily Dickinson was an American writer who wrote in English, or John Dos Passos. Language to me is the same as air you breathe. I take it in, and I release it. Then I suck it in again, and by virtue of this simple exercise, I stay alive.

M. P.: How do you think it affects the characters when their lingua franca is English (their dialogue, their thoughts). Do you think it changes who they are?

H. N.: If I write about characters whose language is English, there is no language question in terms of language per se, but there are questions vis a vis the characters’ social class, education, intelligence, regional provenance, and so on, which, of course, always inform speech. That goes for characters who think in Spanglish, Cajun- English, or any other linguistic hybrid. I must tell it as it is, the way an actor must do a perfect accent and not a mockery of one or a soprano must hit that perfect c over high c and nothing in between. I hear it, I know it, and I do it.

If I write about a character whose English is wanting and/or speaks in translation, then that is reflected in how his/her speech pattern is expressed, and it is up to my artistry to convey that.

If I am writing about a character who is speaking in, say, Spanish, I convey that with my own linguistic sleight of hand and may pepper his/her sentences with Spanish words for Sazón and coloratura. You can find an example of this in Chapter 5 of Princess Papaya with the character named Dolores, a Cuban living in Cuba, who is forced into prostitution as a means of survival but ultimately uses it as a private weapon against the Castro regime.

If you are asking me whether language changes the way people think, the answer is both no and yes. No because underneath all language is the universal human language. Yes because each culture has a predetermined set of values and its own singular weltanschauung, which informs both linguistic meaning and intent, as well as what you say and what you don’t say.

It is up to the writer’s own art and genius to modulate all that within the text and context of the novel itself—never letting it stick out like a thesis, as that would not be literature. In the end, one’s work must be a seamless garment, and the reader should understand and discern the story intuitively, not be expected to dissect it like a frog.

M. P.: How do you feel about translations of your own work? Do you play an active role, or do you view the translation as a separate artistic product?

H. N.: I do not like to translate my own work at all. It would be like saying something twice and second-guessing myself in the process. I’d rather spend the time working on something new. However, I do like to check for accuracy and fidelity with a fine-tooth comb.

M. P.: Your characters occupy a very real and familiar environment, and yet they witness magic in their daily lives. Is that your view of the world or is this something unique to the Cuban American communities you’re depicting?

H. N.: I suppose the same way my left brain interacts with my right brain. The one needs the other. I don’t know that life through the magic lens is unique to the Cuban-American experience per se. Perhaps it has more to do with the artist’s eye—or this artist’s eye.

M. P.: Do you privilege fiction or non-fiction? Do you think either is more powerful or more apt to tell a particular story?

H. N.: Do you mean prefer or lean more to one or the other, like favoring the right leg over the left? Well, in any case, the two are not related at all. Writing fiction is the same as composing music. The artist is born. I did not choose it. I just am. There is no preferring there. A writer writes. No sense asking the mocking bird why it sings.

M. P.: Is your work autobiographical?

H. N.: My fiction is not autobiographical. Perhaps someday I’ll write my memoirs or some memoirs and that will be autobiographical. As I said before, I write what I live, feel, see, know, remember, and touches my human heart. And, to borrow from Whitman, I contain multitudes. I weep with those who weep, and I am not alien from the human condition.

M. P.: All of your work very much weaves in the intersection of society’s mores and values with the lives of individuals. In this novel, several of your characters represent people that are often critiqued by mainstream values: the doctor giving abortions, the curandera, couples engaged in forbidden affairs, the hermaphrodite. Are you drawn to these characters?

H. N.: Yes, those characters clamor for a voice, long for grace, understanding and transcendence. I’m interested in considering the whole of them from an independent lens. I ponder their contradictions and complex humanity away from the myopic eye of prejudice or condemnation or society’s expectations.

M. P.: I recently saw a film by a young filmmaker about Cali, Colombia. She said that she wanted to focus on a positive depiction of Cali since everything she’d seen was negative. Do you feel pressure to represent a particular community? Are you concerned about negative depictions of that community?

H. N.: No, I don’t feel any pressure to represent any community. I am not interested in propaganda or morality plays where characters stand for things or ideas or, worse, ideals. I don’t want to spin anything, good or bad. It’s both song and knee jerk reaction. It is, ultimately and fundamentally, poetry. Robert Lowell said, “It’s not what a poem means but how a poem means.” That’s what my literature is about, how.

M. P.: I had a professor who argued that the tradition of the public intellectual critiquing the American lifestyle in newspapers and essays was dying. You’re a scholar, a fiction writer, an essayist, and a radio commentator, which puts you in a wonderful space to comment on the culture around you. What do you think are the responsibilities of intellectuals today? Do they have a place in the community at large?

H. N.: I do agree that, certainly, the bully pulpit as literary genre where the thinker/essayist lambastes injustice seems to be defunct—but the advent of the blog is perhaps filling the void that your professor identified, though not entirely.

I believe everyone is called upon to speak out against unfairness and to relieve human suffering in one measure or another. And, of course, from whom much is given, much is expected. So, if a writer can articulate the wrong and the right and point the way to solutions, then he/she must speak out, write and shout and say “ouch!” for as long as it takes in as many venues as possible. To stand by silently and let oppression rule in any guise is not acceptable in my view.

M. P.: And the dreaded question: Are you working on anything new?

H. N.: I’ve finished a novel about Chinese slave trade in the US and am working on a story (a novel) about destiny/providence. I’m also drafting a lot of letters in defense of same sex marriage and undocumented immigrants these days.

Posted: April 3, 2012 at 8:32 am

Aug 14,2015

Dear Himilce, Are you in Havana today?

Did I just see you going into the US Embassy there?

I knew you’d return in your lifetime!

RSVP ASAP & BON RETOUR, Angela