36 Years With Sinéad

36 años con Sinéad

Adriana Díaz Enciso

…She came from Ireland, and in the tragedy of her personal story and that of her siblings she saw the embodiment of the tragedy of her country, suffocated by a castrating and cruel Catholic church that oppressed women in particular, as well as by its wounded geopolitical reality. What this rock and roll Joan of Arc was doing was utterly serious.

The Lion and the Cobra

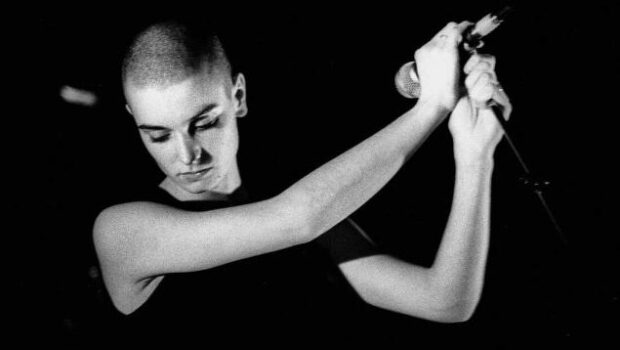

Sinéad O’Connor’s first album appeared in 1987. When I moved to Mexico City shortly afterwards (I was born in Guadalajara), I took it with me in my scarce baggage. It had to be kept near. No other record started with the ghostly lament of a woman who has lost her lover at sea, the rawness of her grief expressed with impeccable poetic enunciation and a powerful voice that, while completely new, seemed also to be rather ancient. That first song, “Jackie”, was followed by “Mandinka”, a thoroughly pop number, the chorus of which—I don’t know no shame/I feel no pain/ I can’t see the flames—was intoned with verve by a slight, hairless young girl with an equivocal fragile appearance, who could take us aback at any time showing her ferocity.

The Lion and the Cobra is full of unforgettable songs; its lyrics, cryptic to a considerable extent, reveal a maturity that no one knew how such a young woman had managed to reach. It is also an album of contrasts: the rage in “Jerusalem” next to the tenderness in “Just Like you Said It Would Be”, for instance. I remember listening to the latter with my dear friend, author Verónica Murguía, going over the lyrics, voice and instrumentation thinking, “it’s not possible, such a beautiful song”.

I also listened to this album with another dear friend, poet Laura Solórzano, in the flat we shared in the Zona Rosa, both newly arrived in the capital, and with singer Rita Guerrero, who was like my sister, and was equally thrilled at having discovered Sinéad. At the mythical Bar 9 we danced to “Mandinka”, O’Connor’s bald head spinning round in the video projected on a screen. This wasn’t only rock and roll. What this Irish girl was doing was mysterious, it came from profound sources, and obeyed no pre-established concept.

Who doesn’t remember “Troy”? That love song that is like a bomb, an open-heart surgery that we barely survive, yet want to listen to again and again. “Troy” was also a song for Sinéad’s mother, who had recently died in a car accident, and the whole album is dedicated to her.

(Fast forward to 1998: the man who’s about to stop being my husband is driving me to Cuernavaca, following doctor’s orders, so that I recover from a nearly fatal pneumonia. In the car, we listen to “Troy”. He asks me to translate the lyrics for him. I do, with a lump in my throat.)

Typical of O’Connor, that piece, which is all grief and inner world, paves the way to “I Want Your (Hands On Me)”, another pop song, the subject matter of which is, basically, sheer lust. It is followed by “Drink Before the War”, another enigmatic song of sorrow, rebelliousness and an enormous beauty, and the hypnotic “Just Call Me Joe” (not authored by her). The Lion and the Cobra concentrates the artistic integrity, the tenderness and beauty, the occasional pop frivolity, impeccably wrought, the irrepressible fury, the religious feeling, the poetry and the questioning of the status quo, all of it expressed through an exceptional voice that moves from whisper to howl, and which would mark the singer’s career.

O’Connor recorded this album when she was 20 years old, pregnant with her first child, resisting the record company’s pressure for her to have an abortion. She had already challenged the imposition of a first producer who didn’t understand her work and ended up producing her debut album herself. She had equally defied the demands to adopt a public image according to what a female pop singer was supposed to be in the most radical way possible: shaving off her hair. However, with hair or without it, it was impossible not to be hypnotised not only by her voice, but by her implausible beauty. Her image was aggressive and fragile at once, entirely unclassifiable. She truly seemed come out from another world, a world about which we knew nothing, but which we urgently wanted to enter.

Soon she would start telling us herself where she came from: fracture, violence, child abuse at the hands of a mother with severe mental health problems, and whom she dragged along as a terrible ghost up to the moment of her own death. Furthermore, she came from Ireland, and in the tragedy of her personal story and that of her siblings she saw the embodiment of the tragedy of her country, suffocated by a castrating and cruel Catholic church that oppressed women in particular, as well as by its wounded geopolitical reality. What this rock and roll Joan of Arc was doing was utterly serious.

The Lion and the Cobra also accompanied me when I came to live in London in 1999. For nearly 40 years I’ve kept on listening to it, and the world kept on listening as well to that frank and courageous voice, almost always right, other times lost and desperate.

I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got

I bought O’Connor’s second album in vinyl when I lived in a tiny little cottage, out of a fairy tale, in Olivar de los Padres, shortly after coming out of hospital, where I had been admitted for anorexia. I can still see the somewhat dark corner where the record player was, next to my desk; the record’s cover with O’Connor’s face in close up; those eyes. I listened to it over and over, while I wrote my first literary reviews for “El Semanario”, the cultural supplement of the Mexican newspaper El Universal, under the generous editorship of the much missed José de la Colina and Juan José Reyes, who opened the doors to so many then young authors.

I was going through the process of becoming a real writer, entering the public dialogue, while I recovered from a terrible physical and mental health crisis, and Sinéad’s company was indispensable to me. I remember one afternoon at Laura Solórzano’s flat (she was now living in the Condesa neighbourhood), talking about this new album and the depth in many of its lyrics.

The album starts with the “Serenity Prayer”. What follows is O’Connor’s progress to another level of maturity, saturated with poetry, including that of others, as is the case of her rendering of the Irish anonymous 17th Century poem, “I’m Stretched on Your Grave”, which closes with a violin uproar. As an example of O’Connor’s own poetry I mention “Three Babies”, a song of grief expressed through infinite tenderness. She would later state that the song refers to three miscarriages, though it may also be about the abortions she also said she’d had. In any case, from that complex boundary, O’Connor gave birth to a beautiful loving song to unborn babies.

There are also pop songs with barefaced confessions of her personal life (O’Connor isn’t O’Connor without them), the condemnation of racism and inequality in Thachter’s England in “Black Boys on Mopeds”, and songs where Sinéad talks about the fame that had befallen her, taking her by surprise and in a shattering way, being so young. Since then, she already saw with lucidity the mix of misunderstandings, falsity and filth in the music industry. She had entered that world with eyes wide open, willing to tell her truth with no concessions, without ever allowing anyone to shut her up, dogged and rebellious.

Among that second album’s material, the song, authored by Prince, that definitely catapulted her into international fame, “Nothing Compares 2 U”, fits uneasily. I know that what I’m saying will sound like blasphemy to her fans, and the song was one of O’Connor’s own favourites. However, in my opinion, it is too obvious, dull pop, memorable only because of her rendering (everything she touched, in her numberless covers of other artists, she seemed to turn into gold)… and, of course, because of that spontaneous tear in the video. The fame it brought to her was a curse in many ways. Somehow, she had that intuition. In Rememberings, her autobiography, she talks of how she burst into tears, and not of joy, when they told her that the album had become number one.

I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got’s last track is its title’s song, a cappella, an intimate chant of the soul, of spiritual pilgrimage, which talk about what were Sinéad O’Connor’s constant fight, highest aspiration and courage. The world of pop wasn’t prepared (it never has been) for something like this.

Old songs and ravaged children

O’Connor decided to counteract the success of I Do Not Want… in the pop scene with an unexpected new album, as distant as possible from that universe in which she felt lost, and to confuse everybody. A “red herring”, as she called it in her autobiography. Am I Not Your Girl (1992), is made up of old Broadway “show tunes” and favourite jazz standards, part of the music she’d listened to when growing up. But, it being O’Connor, the record isn’t in any way a mere divertimento or nostalgic exercise. The sexy and bitchy potency of “Why Don’t You Do Right” is followed by the doleful tenderness with which O’Connor transmutes Ella Fitzgerald’s “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered”, setting the tone for the whole album. O’Connor resuscitates these songs with her characteristic emotional energy, the mastery of an exceptional voice and an impeccable orchestra. More than a red herring, it’s a jewel that alerted us all about her wide-ranging musical talent and power as a performer.

The album includes “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina”, a favourite of her mother’s. I’ve never been interested in the multiple versions of this piece’s melodrama, but in O’Connor’s voice it becomes something else; it’s as if her bare emotional tension penetrated every interstice in a song, either hers or somebody else’s, and transfigured it. The last song is a moving version of the folk ballad “Scarlet Ribbons”, pierced through by her Irish roots.

It may be worth mentioning here that this album was perhaps my last meaningful attempt at getting close to my estranged sister. I knew she liked those old songs, and I gave it to her during a visit to Guadalajara. I never found out what was her opinion, though my father did take a peek and bothered to make fun of it next time he saw me. (There was logic to it; only I could have thought of planting a Sinéad record in that house). The target of my father’s mockery was the desperate text at the beginning of the CD’s booklet, about the vulnerability of abused children, with obvious references to O’Connor’s own experience at the hands of that unhinged mother of hers who, though now dead, she kept on trying to love. The text goes even further: it identifies the entire world and its misfortunes with that injured child, and states that the answer is love, and God, “which is Truth – only, The True God”.

The album’s last track is an extraordinary declaration of (spiritual) war against lies, against God’s and Christ’s enemies, and, specifically, against the Holy Roman Empire. There’s no music here; only Sinéad’s voice, a bridge between her rage and pain and her listeners’ experience: “Can you really say you’re not in pain like me? Are any of us not living painfully?” And she goes on: “God said: ‘I bring not peace, I bring a sword’”. Sinéad bore, no doubt about it, her own flaming sword, and was about to brandish it in an act that would make the rebelliousness usually associated with rock look like kids’ stuff.

In those statements, O’Connor made clear that she had a mission, and it wasn’t only singing. She wanted to denounce child abuse with the urgency the issue called for and draw attention to its repercussions through an integration of personal suffering and the suffering of the world, which, she thought, could only be healed through justice and spiritual intervention.

Throughout her career, this endeavour drew to her many followers who had experienced a similar kind of suffering. In my case, it would be absurd to pretend that I didn´t also find an echo in Sinéad’s voice, having known my own version of familial hell, but I think it’s important not to simplify this aspect of her public voice. Making personal pain public isn’t necessarily a virtue. What is extraordinary here is that someone was capable to create so much beauty out of her grief; so much new and thrilling music, with inexhaustible talent and intelligence. What is captivating in Sinéad O’Connor, on a profound, true sense, beyond all the scandals associated with her in the show business press, are her music and her voice at the service of a transfiguration, which she always considered spiritual, of personal experience into a universal language that transcends it.

And the Pope

The question as to whether her declarations of war were the adequate means to engage in this fight, whether music was not enough, wasn´t entirely irrelevant. From a certain perspective, her discourse could seem naïve, out of place, but such a question rose from a practical—not to call it prosaic—approach to social exchange. O’Connor joined the battle the only way she could, aware that now, due to her fame, the entire world would potentially listen, and if she shouted loudly it was because hers was a desperate struggle. Since in her assertions (in interviews, in her albums’ booklets, in that bonus track in Am I Not Your Girl), O’Connor spoke with truth, however impulsively, I think that criticism obeyed the fact that she wasn’t being listened to with enough attention; that the world was hardly used to the frankness of innocence—in the best sense of the word—that is usually accompanied by great courage.

What was truly sacrilegious for those pulling the strings in the music industry was to be saying these things in that context, when what was at stake was, as usual, a lot of money. But Sinéad, as we have already seen, challenged that industry since she recorded her first album, and kept on doing it throughout her life. We may remember when she shaved on her head Public Enemy’s logo to appear at the Grammys, when they still refused to acknowledge the value of rap or hip hop; or when, the following year, she refused to attend the ceremony because the music industry revolved around commercial rather than artistic principles. She didn’t lack a sense of humour: when many people burnt her records in the United States because she refused to have the national anthem sang before one of her performances, she disguised herself with a wig and sunglasses and joined the protest.

However, when she tore Pope John Paul II’s picture live in the Saturday Night Live programme in 1992, her crusade reached another level. The photograph had a personal meaning for her: it used to hang on her mother’s bedroom’s wall. O’Connor picked it up when she went there with her siblings to sort her things out after her death. The moment is well known, it can be watched on You Tube, and thousands and thousands of words have been written about it: after singing, a cappella, “War”, Bob Marley’s adaptation of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie’s 1963 speech in the United Nations, where he denounced racism, and changing some of the lines in order to declare war against child abuse (which, for her, was proof of the existence of evil in this world), Sinéad, staring at the camera, says: “Fight the real enemy”, and tears the Pope’s picture. For her, the Pope symbolised that evil, the institution which had caused such harm in Ireland, where the rate of child abuse was then extremely high, and perpetually covered up by the Church. O’Connor would state that the Vatican was the first to lie about it, as well as responsible for many forms of historical violence, in the name of God, for no other cause than power and money. She also said she had done what she did in order to start a discussion, and because the Church should be overthrown: “its days are numbered”, she said several times. Her firm defence of this action before the media, overcoming her natural shyness with conviction and acuity, was electrifying. She knew very well what she was doing, and she knew there would be a price to pay.

Again, the public discussion around this issue was somewhat frivolous: about whether this had been a childish gesture, or a lack of respect for other people’s religious sensitivity. Most were simply not listening, nor paying attention to the fact that this action came from a profoundly religious woman.

Punishment came swiftly, exemplified in the booing she was subject to shortly afterwards during her performance at an homage to Bob Dylan (her great hero), in one of the most dramatic scenes in rock history, but O’Connor was undeterred. When people told her that she had just destroyed her musical career, she used to respond, with no little humour, that what she had destroyed was the career of the record company’s people, who would be no longer able to make money out of her in order to buy their summer houses in some exotic beach. To her, taking that step meant, among many other things, her true liberation from the music industry’s yoke. She had made things abundantly clear. She was able to go on making whatever music she liked, and though she never had a commercial number one again, that was what she cared least about. She might be constantly causing offence, but the extent of her talent meant that she would never stop singing, creating brilliant albums, collaborating with other artists in a creative effervescence that bore many fruits, and that there would always be people willing to listen.

If her action was deemed at least childish thirty years ago, history has proved her right. Nevertheless, that doesn’t change the fact that it was thirty years during which O’Connor was, one way or another, vilified and ignored by many (many of those who now, after her death, wring their hands and talk about her legacy). Eventually, being constantly and publicly treated like a pariah took its toll, even more so when this woman was as fragile as she was strong, dragging the consequences of the extreme abuse of which she had been a victim. In order to understand the consequences of the Pope’s picture incident in her career, I recommend watching the film Nothing Compares, about which I’ll speak later.

As years went by, however, Sinéad remained on a war footing. We saw her many years later dedicating to the Pope her passionate rendering of Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changing”, with an enormous crucifix around her neck. “Take Off Your Shoes” from her 2012 album How About I Be Me (And You Be You), the incendiary lyrics of which is no playing matter, is one of her most powerful hymn-songs. With its refrain, “Take off your shoes, you’re on hallowed ground”, it’s nothing less than the voice of the Holy Ghost speaking to the Pope and the Vatican about the Church’s abuse scandals (“even you can’t lie when I’m around”.) The lyrics is fearsome in its declaration of truth, in the way that only the things of the spirit can be. I can well imagine two or three cardinals listening to it and running for their lives. This song is the mature culmination—sustained, precisely, by the spirit—of that tearing of the Pope’s picture twenty years earlier in live TV.

Peter Gabriel and Universal Mother

In 1992, Peter Gabriel’s US was a sensation. It is still great, enriched by O’Connors’ collaboration in some of the songs. Shortly after the album’s release, Gabriel’s tour made it to Mexico. I remember quite clearly how, before the gig, there was this rumour that Gabriel and O’Connor “had something going on” (it was true), and that O’Connor had made some “scenes”, including a pills overdose. The gossip, casual and cruel as it usually is around the famous, concluded that, of course, we already knew she was crazy.

O’Connor came in the tour. The gossip vanished the moment she climbed onstage, barefoot, slight and graceful, with an absolute mastery both of the stage and her voice. She was a presence of great beauty, and not only external, which made everyone shut their mouth.

From her relationship with Gabriel (who wrote a brief but moving tribute on Sinéad’s death, acknowledging her talent, her indomitable spirit, her integrity and the difficulty of the path she had chosen), we’re left with the memory of those concerts; their collaboration in US, in particular in “Blood of Eden”, a song about the union of man and woman, in the video of which O’Connor has a hypnotising aura that seems almost supernatural, and “Thank You For Hearing Me”, the song she wrote for him, released in her 1994 album Universal Mother.

Universal Mother was considered by O’Connor one of her most special albums, and with good reason. It is perhaps my favourite, and a work of full maturity. The cover is a strange drawing by herself, a tad naïve, where a naked figure in the midst of a whirling starry sky is lifted, firmly and tenderly, by a kind of deity. The album is dedicated “as a prayer from Ireland”. In the first track we listen to Germaine Greer talk about a world without patriarchy, the opposite of which wouldn’t be matriarchy, but fraternity; in the booklet we read the neo-pagan poem “The Charge of The Goddess” and “He Thinks of Those Who Have Spoken Evil of His Beloved”, by W.B. Yeats. There’s also a picture of Sinéad holding her son Jake (who makes his own intervention in one track).

What, then, is Universal Mother? The first piece, “Fire on Babylon”, is a conflagration, a flare of fury that, in Sinéad’s most powerful voice, with a bass counterpoint, subverts child terror, abandonment, motherly violence and madness, burning everything in its wake. It’s an exorcism, as much as the official video, in which a “child Sinéad” fights that primary evil, transformed in Joan of Arc; an extraordinary warrior hymn that still shakes me.

It is followed by a journey through maternity’s infinite faces, with a good deal of serene, tender and often cryptic songs, the lyrics of which are plain poetry. The whole album is woven with beauty, simplicity and depth at once, sown with ghostly images that vanish like a whisper in Sinéad’s voice. There are lullabies and love songs—not necessarily romantic or sexual love, but a boundless love that flows through the whole album, as if rising from a renewed spring. With the paradoxical nature of everything O’Connor did, it is run through by infinite joy and infinite sadness, often indistinguishable. It includes a cover of Nirvana’s “All Apologies”. Kurt Cobain had just committed suicide that year, and Sinéad delivers a beautiful tribute, turning that song of hopelessness and self-flagellation into an offering full of tenderness, with only her voice and acoustic guitar. We also have a desolate a cappella lament in “Tiny Grief Song”, with only three lines repeated like a litany: “I’d a terrible broken heart/You were born on the day my mother was buried/my grief my grief my grief my grief”. This trend of the album culminates in “All Babies”, which is, in my opinion, one of the most beautiful songs ever written. It’s impossible to describe: listen to it, and to its lyrics. Even if it were the only thing Sinéad O’Connor had ever done in her life, just for that song she would have been a great artist.

Apart from “Fire on Babylon”, rage in this album is concentrated in “Red Football”, a call against physical and emotional violence that rises in intensity until it becomes a wild rebellious chant, as well as in “Famine”, a rapped piece that borrows the chorus from the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby”. There, the political O’Connor emerges from the former delicate inner world in order to open herself up to history. The subject matter is Ireland; the reality behind the 1847 famine; that country’s suffering and social and political causes, and a theme crucial to her: Ireland seen “as a race like a child that got itself bashed in the face.” The official video features a beautiful O’Connor, perfect like a fashion model, but the words coming out of her mouth have never been heard from a model’s mouth, or from what we understand a pop singer to be. O’Connor was constantly crossing those borders, turning everything upside down, going to the depths of things without giving the listener time to prepare themselves, and making many people very uncomfortable.

Universal Mother is therefore what the title says. The loving, fecund, life-giving woman, at moments goddess; the cruel mother, an infernal destructive force that must be exorcized; the loving recovery of childhood and, finally, the mother as motherland. It’s a supreme production from beginning to end. I’ve been listening to it for thirty years.

Faith and Courage

O’Connor’s following album, Faith and Courage, was launched six years later. By then I had just arrived in London, after my divorce. I didn’t know anybody. It was a very exciting adventure, but also hard, and that album kept me good company. It’s the result of O’Connor’s resurgence to life after a profound depression and a suicide attempt; a work of fortitude and purification. It is, clearly, a chronicle of her recovery, not so much psychological as spiritual. It is intimate and beautiful, with some of her best lyrics. I listened to it many times, in particular when I felt lonely, lost, shattered by divorce and self-exile (not withstanding how much I loved London), and it always did me good. Back then I used to rent a room in Shepherds Bush, and I remember watching one night on TV a programme whose presenter was, at the time, one of rock’s most famous commentators: always smug and insufferable (what’s her name again?). That night she was commenting on ”No Man’s Woman”, a song in this album, where we see Sinéad dressed as a bride, who flees the registry office, gets rid of her veil and the white dress and ends up on her own, happy, with her guitar. The commentator was openly laughing at her. “I don’t understand, what’s all that about?”, she said, with a derisive smile. True, not many songs in the pop scene talk about rejecting men’s imperfect love and finding plenitude in a lover that is a spirit. But it makes perfect sense in O’Connor’s universe, and it’s also a great rock song. What lay behind the now forgotten presenter’s mockery was, in no veiled terms, the insinuation that O’Connor was mad, and that we all knew it.

I guess she couldn’t appreciate either the love (or lost love) songs in that record, powerful like a punch even if sung with the sweetest voice; those born from a profound intimate joy, or the lament, for which O’Connor had a nigh supernatural talent, here embodied in “Hold Back the Night” (a song by Robert Hodgens).

However, not everything in O’Connor was torment. She also had a markedly playful and brazen side. One example is “Daddy I’m Fine”. It isn’t in any way one of her best songs, but it’s still interesting to hear her reminiscing about her arrival in London at 19, telling her father not to worry, for she’s happy making music, going on stage and wanting to fuck every man in sight.

The album ends with a “Rastafied” (the term is hers) version of the Kyrie Eleison, the beginning of the Catholic mass, “just for mischief”, as she claimed in her autobiography. The booklet bears a Rastafari quote glorifying God, and the album is dedicated to “all Rastafari people, with thanks for their great faith, courage and above all, inspiration”. It was in the London Rastafari community that O’Connor found refuge during the first years of her career, when she felt lonely, alienated from a music industry that had become her world without her truly wishing it, and with them she continued the questioning in her search for God. That is the subject matter, along with those of Ireland and her own story, of the “The Lamb’s Book of Life” reggae in this album.

Another O’Connor album that has kept me company for years is the 1997 EP Gospel Oak, a short collection of pieces that, just as in Universal Mother, turns around the diverse ways of motherly love, the redemption of pain, a “child state” of the soul. As is often the case in her work, it’s as if she were herself both the person who receives and who gives that love through the intervention, spiritual without a doubt, of something or someone “other”. This is certainly the case in “This is to Mother You” and “I Am Enough For Myself”. Her tenderness is extended to ”Petit Poulet”, a song inspired by the massacres in Rwanda. In Gospel Oak, O’Connor transfigured again pain into beauty with her voice, her lyrics and her mastery of several musical genres that she fused freely. The same voice of a soul that looks after another speaks in many of her love songs, opening on occasion to the broader world, as she does in “For my Love”, about Ireland’s pain. Following this logic, in “This is a Rebel Song” she also transforms, delicately and deeply, the conflict between England and Ireland into a love song. The EP is sealed with an imposing live rendering of the Irish traditional song “He Moved Through the Fair”: the song of a ghost lover.

Gospel Oak’s cover is a photograph of the railway bridge in an area of northwest London. That’s where O’Connor attended the surgery of the psychoanalyst that she was seeing during a time of enormous loneliness. Sometimes I pass through that area, and I then think of this brief and beautiful record. I also think of O’Connor’s loneliness.

Sean-Nós Nua

In 2002 O’Connor launched Sean-Nós Nua, a selection of traditional Irish songs she’d grown up with, suffused with melancholy, revealing again the extent of her curiosity and love for music in the most diverse genres. Though it reached number one in Ireland, the goal wasn’t commercial success. I quote part of what she wrote in the booklet, where the aim is made clearer: “Many of the songs in this record are stories of enduring and unconditional love, love that can’t be quenched by fires or floods. They are the beautifully borne pain of real people, who really existed. They teach that pain can be made into something positive and beautiful when one sings it, and so pain can be healed by singing, since songs are magic. I consider all of these songs magical prayers and therefore not sad songs at all. They are only sad to those who cannot feel the true ghosts of the people who are speaking through the songs. Love, and only enduring love, is the lesson they are giving and therefore, utter joy. They show that the soul is everlasting.” The text ends saying, “All Glory to Jah in the highest”.

O’Connor’s rendering of these pieces is indeed impregnated with that ghostly atmosphere, delicately embodying the longings, the grief and joy of generations that are no longer here, bursting with emotion. They are, all of them, incredibly beautiful. In a documentary on the album’s recording, Sinéad talks about the need of pouring a full emotional force into singing, even if there are people who’d rather not hear, “for fear of being shattered by a song”.

In 2003 O’Connor passed through London in her tour to promote this album. Those were hard times: during that spring, the UK was preparing, whether we wanted to or not, for the invasion of Iraq, despite the one million people’s march who had said NO on a freezing February—a NO that Tony Blair decided to ignore. It was a horrid moment of hopelessness, of rage, sorrow and fear. Simulated attacks of biological weapons were being conducted on the underground. My friend Eloise Kazan was visiting, and we were both pondering on how we could build a shelter under the stairs. We couldn’t think of what would be useful in the case of a biological weapons attack. We went to buy water, chocolates; we had a torch and blankets. Our shelter was so absurd that it ended all in laughter, and we reached the conclusion that, should such an attack come to happen, there was absolutely nothing we could do.

We went together to O’Connor’s concert at the Hammersmith Apollo. It was a sort of purification. Sinéad dedicated the first song, “Paddy’s Lament”—a war lament—to Clare Short, then a member of Tony Blair’s government, who had just warned she’d resign if the United Kingdom went to war without the United Nations consensus. Onstage, between songs, O’Connor was casual, laidback, and very funny, telling irreverent jokes, but the moment she started singing there was a complete silence in the theatre, and its space was transfigured. She was possessed, in the best sense of the word. I wrote a review of that gig, I don’t remember for which journal; I’ve only found the manuscript, from which I share an excerpt here, since it reflects my impression of the concert in such dark moments:

“We witnessed the full force and ferocity that characterize Sinéad O’Connor’s work, but also the joy, the gentleness and tenderness which are an equally inextricable part of her music. If it’s ever been clear that the cult to personality is dangerous and stupid, that musicians and singers are the vehicle of a power inexpressibly superior and vaster than the individual who sings the song and those who listen to it, that the stage is a sacred space, and song is sacred, it has been here”.

Last albums

That year, 2003, O’Connor announced (it wasn’t the first time, and it wouldn’t be the last) her retirement from the music scene, saying she wanted to have a normal life, where her privacy would be respected. As farewell, she launched a double album. Its first record opens with liturgical hymns in Latin, followed by an eclectic collection of B-sides, pieces previously unrecorded, collaborations with other artists and idiosyncratic covers, such as that of Nazareth’s “Love Hurts” (a wonder!), and even Abba’s “Chiquitita”, to which she gives a soul, however implausible it may seem. There are electronic pieces, such as the dark and strange repetitive lament in “Love is Ours”, and it ends with the most beautiful “Song of Jerusalem”, a traditional song where tenderness and sorrow are intertwined. The second record is a concert at Dublin’s Vicar Street Theatre. The album’s title? She Who Dwells in the Secret Place of the Most High Shall Abide Under the Shadow of the Almighty, taken from Psalm 91, the same one from which the title of The Lion and the Cobra had sprung 16 years earlier.

Luckily for us, O’Connor didn’t retire. There were still a handful of records to come, starting with “Throw Down Your Arms” (2005), produced by Sly & Robbie, permeated by the Rastafari influence. The cover is a picture of hers on her first communion, surrounded by Celtic ornaments. Sinéad was still looking for herself, in an obsessive swaying between finding and contriving who she was. The first piece in the album is chanted a cappella: “They tried to fool the Black population by telling them Jah jah dead”, with the repeated chorus: “Jah no dead, oh no Jah no dead.” It is, in fact, a prayer. The whole contents of the album’s impeccable reggae songs is religious, in the Rastafari prophetic register, and ends with a new version of “War”, the Bob Marley’s song that gave O’Connor the strength to tear the Pope’s picture many years before. She was still on a war footing.

How About I Be Me (And You Be You)?, of 2012, was purportedly a less personal album than the previous ones. I’m not sure she managed that. In any case, in my opinion it’s her weakest production, with some obvious and simplistic lyrics, though it does include the extraordinary “Take Off Your Shoes” (the Holy Ghost’s voice I’ve mentioned above).

Since O’Connor was ordained as a priest in 1999 (I’ll come back here later), we had become used to see her wearing a cassock, or at least big crucifixes. Instead of that, in the cover for I’m Not Bossy, I’m The Boss (2014), we see her as a dominatrix, with a wig and latex apparel. Described by herself as an album of pop love (and desire) songs, and produced—as much of her work—by loyal John Reynolds, her first son’s father, it starts, misleadingly, as a lighter and more frivolous record, with some effective tracks: pop, rock, blues, with Brian Eno on keyboards. It’s too long and some pieces are weak, but in many others her mastery’s hallmark is intact, as is the case of “The Voice of my Doctor”, hard rock with blues’ roots and powerful guitars, a ground where O’Connor hadn’t ventured before, and it’s wonderful to hear what she could do with her voice in that genre. “Harbour” is O’Connor at her best: it starts with a profound sadness that peaks into fury, again touching the extremes of hard rock, in this case close to grunge. Only love songs? “8 Good Reasons” talks about the reasons that curbed her suicidal urges when she felt a stranger in the world, invisible not despite, but because of her fame: her four children’s eyes. Then, in “Take me to Church”, she wonders: “What I’ve been singing love songs for”, and the song’s pop lightness is refuted by the longing for healing from pain revealed in the lyrics. There is also the sad and lonesome wisdom of “Streetcars”, in contrast to other songs that are pure lust, with a good dose of humour.

A Blakean Invitation

In 2014 I was the Secretary of the Blake Society in London, and I had thought of organising an event to commemorate the centenary of World War I. It would be called ‘War Is Energy Enslav’d’, a quote from William Blake’s prophetic poem Vala, or the Four Zoas. I thought of inviting Sinéad O’Connor to be in a panel along with an actor and Ben Griffin, former member of the British Army’s Special Air Service, who had left the army and founded Veterans for Peace in the UK. The event would take place on the 11th of November, Armistice Day. I thought that Sinéad would be the ideal voice to join this conversation. The event would end with her singing a couple of songs with her guitar. My invitation letter closed with these words: “I don’t know if you are close in any way to William Blake’s work, but I have followed your career for many years and I find very few artists in the present day that share as you do his pursuit of an all-encompassing, courageous liberation that starts with the freedom of spirit.”

During the following weeks, I was in touch with her manager through emails and phone calls. He told me that O’Connor had great interest in taking part in the event; that it was complicated because she was promoting her album, but they would try to coordinate the dates both of promotion and of the time she wanted to spend with her children between the two legs of her tour. Finally, the dates didn’t coincide, though the message through her manager was always that she was really keen on doing it.

In the end, the event itself didn’t take place. Dark forces started to shake the Blake Society, and soon after I would leave the organisation, but I’ll always be sorry that it wasn’t possible to carry out this project, not only because I would have been so pleased to meet O’Connor, but because I still think that, with her voice, her intelligence, her rebellious spirit and her sensitivity, it would have been an extraordinary occasion, where genuinely important things would have been said.

Priesthood and theology

In 1999 O’Connor was ordained as a priest of the Latin Tridentine Church by Bishop Michael Cox, member of Ireland’s independent Catholic movement, in a hotel suit in Lourdes, France. She received the name Mother Bernardette Marie, though she kept on singing as Sinéad O’Connor. She was right in calling attention to the discrimination of women in the Catholic church, that forbids their ordination, and both her profound faith and her search for an environment in which she could profess and practice it outside the organised church, ordained by a bishop that was, like her, a rebel, make her decision (that she took very seriously) understandable. It was still an unorthodox and controversial decision, and a further example of O’Connor’s unceasing search of her own identity, but her sincerity, her intelligence and her quest for a spiritual path appropriate for her own life were clearly reflected there. Her concept of religious experience as something direct, that doesn’t need the intervention of religion, makes her position complex, to say the least, but there can be no doubt about the seriousness and intensity of her quest, as we can see in this interview for Channel 4 in the UK (from minute 3.08) after the election of Pope Francis.

However, in my opinion her true ministry was always music, and she said so herself many times: to her, singing was a form of prayer. This was never clearer than in Theology, her magnificent double album (electronic and acoustic versions of the same songs), launched in 2007. She said she had wished to do that record all her life, because of her love for the Holy Scripture, and the fruit of her studies on theology at university in 2000. What she wanted was “bringing God off the page. Let everyone see the humanity of God, the moodiness, the emotionality.” All the lyrics were worked from the starting point of the Bible, almost literally, because, in Sinéad’s words, “there are some beautiful songs already written by God in the Scriptures”. In the album she thanks Father Wilfred Harrington, her professor of exegesis on the prophet Jeremiah, who suggested to her to set some scriptures to music, and the Rastafari, “for having being doing exactly that for fifty years; and for having me as a daughter.”

It’s worthwhile to dwell on this album, which is one of the greatest risks taken by O’Connor (musically and in its subject matter, not to mention the commercial aspect). She was, however, victorious. It is the work of her fullest maturity, and an emblem of the sincerity of the union, in her, of music and faith. Here I’ll focus on the electric version (the London sessions), but the acoustic one of the Dublin sessions isn’t mere repetition; it is rather a painstaking recreation of the same pieces that it’s worth listening to. Here we find everything that religion meant for O’Connor: love, forgiveness, mercy, the direct relationship with the divine, her desperate wish for true religion, liberated from dogmas and churches, to spread over the earth.

I wrote about these songs in some journal when the album was released. The following is a summary. The first song, “Something Beautiful”, is her declaration of intent, so to speak, moving in its simplicity: her wish to do something beautiful for God, which she certainly achieved. “Out of the Depths” voices her conviction that God is alone, that he has no voice because we have turned our back on him in order to worship “gold and stone”, as well as her longing for divine unity. There are sublime moments in this record, such as “Dark I Am Yet Lovely”, O’Connor’s musical recreation of the Song of Songs, or “If You Had A Vineyard”, where Sinéad embodies, with a seemingly simple instrumentalization, the prophetic tone to speak about the pain of Jerusalem and Judah, the crying “for every boot stamped with fierceness/For every cloak rolled in blood”, pertinent in 2007 and, unfortunately, even more so today. We also have Psalm 33 in reggae, expressing the need to sing the glory of God. One of the albums peaks is the harrowing “Watcher of Men”, its lyrics coming from The Book of Job—a most sombre lament, emphasised by the instrumentation’s discordant notes, the cello, O’Connor’s whisper overlapped with a take of her voice broken and on a higher pitch. Another favourite is “Whomsoever Dwells”, that starts with a drum machine and strings arrangement somewhat distorted that take on an obsessive rhythm to receive the voice, with a rather effective echo. The source is, again, Psalm 91, which runs through O’Connor’s work since The Lion and the Cobra. Repetitive and hypnotic, it’s a beautiful song of faith and hope perfectly propped up by the R & B choir; a sober yet intense hymn of spiritual fortitude.

There are also some surprises, such as the cover of “I Don’t Know How to Love Him”, the unforgettable piece from Jesus Christ Superstar sang by Yvonne Elliman, which here is absolutely Sinéad, also unforgettable, or “The Rivers of Babylon”, a cover of Boney M’s vital recreation of Psalm 137, but in a more serene version, with folk echoes but rock instrumentation and gospel choirs.

In this album, as is the case in all of O’Connor’s best work, she shows having understood the deepest truth of human pain and its unbreakable link with the spiritual dimension of existence. She inquired into those two fountains all her life, tirelessly, from a position which was rebellious in as much as it was compassionate—because no one, from her perspective, wanted to listen to the good tidings of compassion and forgiveness, and even less to listen to someone willing to dwell so deep into all of our broken hearts. Perhaps that’s what the mass audiences found most unforgivable.

In her autobiography, O’Connor said that Theology was the only album of hers that she would like to take to heaven with her in her coffin, “in the hope that it will make up for what a complete piece of shit I am the rest of the time”. I hope that her wish was granted. It is a record both beautiful and haunting, fruit of a direct and immediate relationship between a woman of faith and her god.

Islam

It is perhaps because Theology seems to me to be such a limpid and truthful assertion of O’Connor’s creed and her religious convictions that I don’t manage to understand her conversion to Islam when she was 52 (taking on the name Shuhada Sadaqat, but, again, keeping her original name as a singer). Throughout her career, up to her conversion, O’Connor was a Christian through and through both in her music and her public statements. Rebellious, yes, on the field of the dissenters and even the blasphemous, but a Christian. Her arguments regarding the reasons for her conversion never seemed convincing to me, not because I consider Christianity above Islam, but because it never seemed to me that they had the depth of her Christian convictions. She also talked great nonsense at the time, which she later recognised as such herself, and which she explained as coming from some of those outbursts she often incurred in because of her mental health problems. I won’t repeat those statements here, because they’ve found their way around the world already, and because, as you have probably noticed by now, this text isn’t about scandal in Sinéad O’Connor’s life.

At any rate, I have no doubt she was sincere, most of all in the sense that she found shelter in Islam as a community, after some infernal years that she described candidly in her autobiography and in numberless interviews and public statements. Certainly, Christian institutions, regardless her fervour, weren’t precisely welcoming to her, one reason why she had written to three different popes asking for her excommunication. On one occasion she referred to the Vatican as a “nest of demons”. In her opinion, the Catholic church was “murdering Christ” with lies. Perhaps her despair for not finding an adequate context for her Christian faith influenced her decision, or maybe this was another way of continuing looking for her true identity.

In any case, her conversion to Islam was a further step in her tireless spiritual quest—a quest that was sometimes erratic and desperate, but always deep, sincere, in which she invested her soul, and for which she had the guts to take on all the risks. Before yielding to the casual judgement of the media or the popular assumption that her conversion was a further manifestation of her insanity, I’d like to close the subject by saying that I can’t think of any example in popular culture between the end of the 20th century and the early 21st in which a genuine spiritual quest has yielded more fruits, or more beautiful ones, than Sinéad O’Connor’s.

Covers and collaborations

We’ve already said that, for Sinéad, singing was a form of prayer, and, on occasion, a vehicle for political dissent. There are moments in her work where both dimensions meet. But O’Connor was also a disciplined, refined and meticulously professional artist, with a curiosity for the most diverse musical genres and open to a joyful submission to them all. Apart from her original work, she recorded innumerable covers of the songs of others, making them hers with unparalleled sensitivity, and she also collaborated with numerous musicians. Some of the results are included in the 2005 album Collaborations. The following (incomplete) list gives us some idea of the fertile breadth of her interests.

We have seen and heard her sing “Mother” with Roger Waters in The Wall; accompanied by Sting playing double bass, and we’ve already talked about her collaboration with Peter Gabriel; with Massive Attack, in its magnificent “A Prayer for England”, she returned to the subject of the protection of children; with the late author, poet and musician Benjamin Zephaniah and Bomb the Bass she intoned another rebel hymn in “Empire”, and she joined another Irish legend, U2, with the excellent “I’m Not Your Baby”, apart from her collaboration with The Edge in “Heroine”. (Bono also wrote for her “You Made Me the Thief of your Heart”, for the film In the Name of the Father). Sinéad blended impeccably with the universe of Jah Wobble, PIL’s former bassist, in “Visions of You” and, in completely different registers, with that of Asian Dub Foundation in “1000 Mirrors” and Afro Celt Sound System’s in “Release”. There’s a video circulating online in which, accompanied by a grand orchestra and The Chieftains (with whom she also collaborated in other pieces), we can see O’Connor, graceful and ultrafeminine, in a rendition of “Baba O’Riley” next to Roger Daltrey’s irrepressible testosterone. In “Wake Up and Make Love with Me”, O’Connor joined with mastery The Blockheads’ sound fusion, and with equal sensitivity she found the perfect register for her collaboration with The The in “Kingdom of Rain”, or for the temperate sadness of “Harbour”, with Moby. We have also her collaborations with Brian Eno, one of the producers of her album Faith and Courage. Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart was another of the producers in that record, and there’s a video in which, next to him, Kylie Minogue and Natalia Imbruglia, O’Connor sings a few songs, including “Sweet Dreams”, which is a delight to watch: a young Sinéad, full of life, in a stunning femme fatale red dress, having fun, singing. Her cover of John Lennon’s “Mind Games” is utterly beautiful, faithful to the original and, simultaneously, purely O’Connor. Her moving rendering of Elton John’s “Sacrifice” gives unexpected depth and beauty to what otherwise is just a bland pop love song. Sometimes, Sinéad really worked miracles. Let’s take as an example her cover of “Silent Night”.

Franz Xaver Gruber’s 19th century carol, with lyrics by Joseph Mohr, became such a popular Christmas piece that, by the second half of the 20th century, it had already lost all charm, becoming a cliché, a song without true meaning mechanically repeated every December. However, in O’Connor’s exquisite interpretation, the song recovers what would have been its original spiritual meaning, and I’d even go as far as saying that it acquires a religious depth that wasn’t necessarily there, however devout its authors may have been. Sinéad is singing it with absolute seriousness. The official video, set in Victorian London, ads charm and enigma to this beautiful appropriation of that carol, O’Connor’s presence being definitely that of a spiritual intercessor, or perhaps a ghost, sweet and unruly at once, conveying its heavenly message.

All the above is just an incomplete sample of some of the covers and collaborations with other artists in O’Connor’s prolific and versatile discography.

The mental health battle

Throughout the years I have written about Sinéad O’Connor on several occasions. In 1996 I published in Hojas de utopía a text where I tried to elucidate the contradiction between the assertions of her right to live her life with respect from others, defending her privacy, and her extremely public disclosure of the most painful and intimate aspects of that very same life, in addition to her tendency to get embroiled in fights with the journalists who attacked her. How could she even think of talking about God and truth with the entertainment media? Could she really be so naïve? In that article I reached the conclusion that the impulse behind O’Connor’s actions was always her religiosity; her conviction that a kingdom of God was about to come, which would consist simply in the revelation of Truth (with a capital), and that her voice and her fame were tools through which she contributed to telling the truth, or at least her truth. I wondered whether O’Connor would win the battle, or would rather succumb to the brutality of the world, which has always vented a savage fury against people like her.

Years later, after a hysterectomy, a diagnosis of bipolarity, long intervals of hospitalization, repeated suicide attempts and generalized mental collapse, that she herself made painfully public, with videos that were almost unbearable to watch in social media, it looked as if Sinéad had definitely lost the battle. After decades of following her work—or to be more precise, of her music accompanying many moments of my life—I found it, like many other of her followers, painful and disturbing to witness that psychological and emotional breakdown. I confess (and I must not have been the only one) that she also exasperated me sometimes: if she didn’t want to be seen as the mad woman that the public opinion pretended her to be, why to make her pain and moments of unbalance so public? That she was desperate was clear, but I wished I had a way to tell her, “Please, don’t do this. Don’t give them more weapons so that they finish the job of crucifying you. Don’t expose yourself like that, please.”

The release of her autobiography Rememberings, in 2021 (which I read after her death on the 26th of July last year) would throw a light that was both moving and shattering on what those years of her life were like, voicing her gratitude to the staff of St Patrick’s University hospital in Dublin, which would become like a second home for her during that series of mental breakdowns. In it, she also talks about the exploitation and abuse at the hands of one Dr. Phil, who, in a moment of extreme fragility, coerced her so that she’d appear in his TV programme.

The book itself is extraordinary, and, typical of O’Connor, alien to any conceived rules. She speaks candidly about her devastating childhood and teenage years, including her stint at one of the infamous Magdalene Laundries Catholic homes for “lost women” in Ireland. She also talks about her career, her ever tense relationship with fame and the music industry, and of the ways in which she looked for a genuine life turning her back to their hubbub and falsity. She talks about love and the loss of love, about her family and children, her vision of the world and her many political causes with spontaneity and depth: this is the voice of a woman of exceptional intelligence and sensitivity, full of wisdom and, at the same time, extravagance. It is also the utterly sad account of an exceedingly long viacrucis: Sinéad O’Connor’s suffering, unfairly caused by others, but where she also has no qualms to acknowledge the times when she provoked it herself, through her sometimes erratic behaviour. One would imagine that such a book would prove to be heavy reading; however, though often distressing, it is written with ease, sincerity and, in many parts, with beauty, as well as with a sharp and irreverent sense of humour that makes us laugh heartily at the most unexpected moments.

The book is also a continuous lament for her mother, and it ends with a letter to O’Connor’s father, asking forgiveness for her actions that were consequence of her mental health problems, and exonerating her mother (whose violence and cruelty run through the book’s pages) from all responsibility. It seems that Sinéad never quite managed to reconcile the contradictions in these feelings.

To read Rememberings just after her death, as I did, was heartrending. It’s clear that her writing reflected her hope in the future, once recovered from those atrocious years of despair, suicide attempts and hospital admissions. She talks there about a new album that she left almost finished before she died: No Veteran Dies Alone, which is also the name of a programme at the Chicago Veterans Administration Hospital, where she had been doing voluntary work, accompanying army veterans who had no family. She was going to enrol on a course for health care assistants, which is what she was planning to do in between recordings and tours. There are joy and hope in the last pages of this moving and extraordinary book, and it’s almost unbearable to read it knowing that, shortly after it was published, her teenage son Shane would take his own life, bringing her down into an abyss of grief from which she probably never recovered, and that not long after that she herself would leave this world that had treated her so badly… and that had adored her so.

In her last video shared in social media shortly before she died, she seemed to have recovered some hope; her move to London seemed to announce a new beginning.

Luckily, she managed to watch the documentary Nothing Compares, directed by Kathryn Ferguson, which is focused on those years of ostracism, mockery and what we now call now “cancelling” after the Pope’s picture incident, and on the extremely high price this woman of impressive fortitude, but also infinitely fragile, paid for her courage. The documentary reminds us of the integrity and near absolute solitude with which Sinéad passed through the public arena, speaking out against all kinds of injustice and abuse, in particular racial discrimination, oppression against women and child abuse, and of the importance of her legacy throughout the world, and specifically in Ireland. We see a young girl of hypnotic beauty that, alternating between shyness and fury, speaks of her convictions with a clarity that is rarely seen, and perhaps never with such integrity, in the music industry, and later the mature woman, bearing the marks of grief and illness, talking with the same conviction, firmly following her path, defiant. Broken, alone, jocular, heroic, magnificent.

Morrissey was right, in his blog’s furious post, regarding the media’s hypocritical reactions after O’Connor’s death, praising her as an “icon” and a “legend”, after decades of ignoring her or, even worse, attacking her with a viciousness that was, indeed, insane. Once dead came the avalanche of tributes and the smiting of breasts, the “she was right” mantra. Everything, too late.

I write this account or tribute (I don’t know quite what to call it) not only as a form of personal gratitude, for the 36 years during which her music has been part of my life, but because Sinéad O’Connor was, is and will be important. Few times has the world seen such talent, and even less such talent joined to unshakeable integrity and courage—an incendiary combination that sowed as much conflict as beauty. Sinéad left us having contributed, in no mean way, to the world being a better place, and for that we should thank her. And go on listening to her.

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Venía […] de Irlanda, y en la tragedia de su historia personal y la de sus hermanos veía encarnada la tragedia de su país, sofocado por una iglesia católica castrante y cruel que oprimía particularmente a las mujeres, así como por su cruenta realidad geopolítica. Lo que estaba haciendo esta Juana de Arco del rock and roll con estos temas iba absolutamente en serio.

The Lion and the Cobra

El primer álbum de Sinéad O’Connor apareció en 1987. Cuando me fui a vivir a la Ciudad de México poco tiempo después (nací en Guadalajara), me lo llevé en mi escaso equipaje. Había que tenerlo cerca. Ningún otro disco empezaba con el fantasmal lamento de una mujer que ha perdido a su amante en el mar, la crudeza de su dolor expresada con una enunciación poética impecable y una voz poderosa totalmente nueva que, a la vez, parecía muy antigua. A esa primera canción, “Jackie”, le seguía “Mandinka”, un tema cabalmente pop, el coro I don’t know no shame/I feel no pain/ I can’t see the flames entonado con brío por una jovencita menuda y sin pelo, de aspecto equívocamente frágil, que en cualquier momento nos descolocaba mostrando su ferocidad.

The Lion and the Cobra está lleno de canciones inolvidables, las letras en buena medida crípticas revelando una madurez que quién sabe de dónde le llegaba a una mujer tan joven. Es también un álbum de contrastes: la rabia de “Jerusalem” junto a la ternura de “Just Like you Said It Would Be”, por ejemplo. Recuerdo escuchar entonces esta canción con mi queridísima amiga, la autora Verónica Murguía, repasando la letra, voz e instrumentación con una sensación de “no es posible, una canción tan bella”.

También escuchaba el álbum con otra amiga entrañable, la poeta Laura Solórzano, en el departamento que compartíamos en la Zona Rosa, las dos recién llegadas a la capital, y con Rita Guerrero, quien fue como mi hermana, igualmente maravillada por el descubrimiento de Sinéad. En el mítico Bar 9 bailábamos con “Mandinka”, la cabeza calva de O’Connor dando vueltas en el video proyectado en una pantalla. Esto no era nada más rock and roll. Lo que la irlandesa estaba haciendo era misterioso, provenía de fuentes muy hondas, y no obedecía a ningún concepto prestablecido.

¿Quién no recuerda “Troy”? Esa canción de amor que es como una bomba, una operación a corazón abierto que apenas se sobrevive pero que queremos escuchar una y otra vez. “Troy” era también una canción para la madre de Sinéad, que había muerto recientemente en un accidente automovilístico, y el disco entero estaba dedicado a ella.

(Fast forward a 1998: el hombre que está a punto de dejar de ser mi esposo me lleva Cuernavaca por órdenes médicas para que me recupere de una neumonía casi fatal. Escuchamos “Troy” en el auto. Me pide que le traduzca la letra. Lo hago, con un nudo en la garganta.)

Típico de O’Connor, ese tema que es todo dolor y mundo interior le abre el paso en el álbum a “I Want Your (Hands On Me)”, otra canción pop cuyo tema es, básicamente, pura calentura. Le siguen “Drink Before the War”, otro canto enigmático de dolor, rebeldía y enorme belleza, y la hipnótica “Just Call Me Joe” (no de su autoría). En The Lion and the Cobra se concentran la integridad artística, la dulzura, la ocasional frivolidad pop de impecable factura, la furia incontenible, el sentimiento religioso, la poesía y el cuestionamiento del estatus quo, expresado todo a través de una voz excepcional que va del susurro al alarido y que marcaría la carrera de la cantante.

O’Connor grabó este álbum a los 20 años, embarazada de su primer hijo, resistiendo la presión de la compañía disquera para que abortara. Se había opuesto ya a la imposición de un primer productor que no entendía su trabajo, y terminó produciendo ella misma este álbum debut. Había desafiado también la exigencia de adquirir una imagen pública acorde con lo que se suponía que era una cantante pop de la manera más radical posible: rapándose el pelo. Pero con pelo o sin él, era imposible no quedar hipnotizados no sólo por su voz, sino también por su inverosímil belleza. Su imagen era agresiva y frágil a la vez, del todo inclasificable. Parecía de verdad salida de otro mundo, un mundo del que nada sabíamos, pero al que queríamos entrar urgentemente.

Pronto ella misma empezaría a decirnos de dónde venía: de la fractura, de la violencia, del abuso infantil a manos de una madre con severos problemas de salud mental, a la cual arrastró consigo como un fantasma terrible hasta su propia muerte. Venía, además, de Irlanda, y en la tragedia de su historia personal y la de sus hermanos veía encarnada la tragedia de su país, sofocado por una iglesia católica castrante y cruel que oprimía particularmente a las mujeres, así como por su cruenta realidad geopolítica. Lo que estaba haciendo esta Juana de Arco del rock and roll con estos temas iba absolutamente en serio.

The Lion and the Cobra me acompañó también cuando me vine a vivir a Londres en 1999. Durante casi 40 años lo he seguido escuchando, y el mundo también siguió escuchando a esa voz franca, valiente, casi siempre certera, otras veces perdida y desesperada.

I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got

Compré el segundo álbum de O’Connor en LP cuando vivía en una cabañita diminuta, como de cuento de hadas, en Olivar de los Padres, poco después de salir del hospital, donde había estado internada por anorexia. Todavía puedo ver el rincón un tanto oscuro donde estaba el tocadiscos, junto a mi escritorio; la portada del disco con el rostro de O’Connor en primer plano, esos ojos. Lo escuchaba una y otra vez, mientras escribía mis primeras reseñas literarias para el suplemento “El Semanario” de El Universal, bajo la generosa dirección de los muy extrañados José de la Colina y Juan José Reyes, que nos abrieron las puertas a tantísimos autores entonces jóvenes.

Estaba viviendo el proceso de convertirme en escritora de verdad, entrando en el diálogo público, mientras me recuperaba de una crisis terrible de salud física y mental, y la compañía de Sinéad me era indispensable. Recuerdo una tarde en el departamento de Laura Solórzano, que ahora vivía en la Condesa, hablando sobre este nuevo álbum y la hondura de muchas de sus letras.

El disco empieza con la “oración de la serenidad”. Lo que le sigue es el progreso de O’Connor a otro nivel de madurez, saturado de poesía, incluyendo la ajena, como es el caso de su interpretación del poema anónimo irlandés del siglo XVII “I’m Stretched on Your Grave”, que cierra con una algarabía de violín. De la poesía propia de O’Connor pongo como ejemplo “Three Babies”, un canto de dolor enunciado con infinita ternura. O’Connor diría más tarde que la canción hace referencia a tres bebés que perdió, aunque podría también tratarse de los abortos que también dijo haber tenido. Sea como sea, desde ese complejo linde, O’Connor dio a luz a un hermoso canto amoroso a bebés no nacidos.

Hay también canciones pop con desfachatadas confesiones de su vida personal (O’Connor no es O’Connor sin ellas), la denuncia del racismo y la desigualdad en la Inglaterra de Thatcher en “Black Boys on Mopeds”, y temas en que Sinéad habla de la fama que le había caído de sorpresa, y de manera demoledora, a tan joven edad. Ya desde entonces tenía una mirada lúcida sobre la mezcla de malentendidos, falsedades y porquería de la industria de la música. Había entrado a ese mundo con los ojos bien abiertos, dispuesta a decir su verdad sin concesión alguna, sin permitir que la callaran nunca, rebelde y tenaz.

Entre el material de este segundo disco, el tema (autoría de Prince) que la catapultó definitivamente a la fama internacional, “Nothing Compares 2 U”, desencaja. Sé que lo que estoy diciendo le sonará a blasfemia a sus fans, y la canción era una de las favoritas de O’Connor misma. En mi opinión, sin embargo, es demasiado obvia, pop sin chispa, memorable sólo por su interpretación (todo lo que tocaba, en sus innumerables covers de otros artistas, parecía convertirlo en oro)… y claro, por esa lágrima espontánea en el video. La fama que le trajo fue a la larga una maldición. De alguna manera, ella lo intuía. En su autobiografía Rememberings habla de cómo se echó a llorar, y no de alegría, cuando le dijeron que el álbum había llegado al número uno.

I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got cierra con el tema que le da título, un canto íntimo del alma, de peregrinaje espiritual, a capela, que habla de lo que fueron la lucha, la aspiración más alta y la valentía constantes de Sinéad O’Connor. El mundo del pop no estaba preparado (no lo ha estado nunca) para algo así.

Viejas canciones y niños violentados

O’Connor decidió contrarrestar el éxito de I Do Not Want… en la escena del pop con un nuevo disco inesperado, lo más lejano posible de ese universo en el que se sentía perdida, y confundirlos a todos. Una “pista falsa”, lo llama en su autobiografía. Am I Not Your Girl, de 1992, está integrado por viejas canciones de Broadway y favoritas del jazz, parte de la música que escuchó al crecer. Pero, tratándose de O’Connor, el disco no es en modo alguno un mero divertimento o ejercicio de nostalgia. A la potencia de “Why Don’t You Do Right”, sexy y socarrona, le siguen la ternura adolorida con que O’Connor trastoca la “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” de Ella Fitzgerald, marcando el tono de todo el álbum. O’Connor resucita estas canciones con su característica entrega emocional, el dominio de una voz fuera de serie y una impecable orquesta. Más que una pista falsa, es una joya que nos alertó a todos sobre la amplitud de miras de su talento musical y fuerza interpretativa.

El álbum incluye “No llores por mí Argentina”, una canción favorita de su madre. El melodrama del tema en sus múltiples versiones nunca me ha interesado, pero en la voz de O’Connor es otra cosa; como si su desnuda tensión emocional lograra meterse por todos los intersticios de una canción, suya o ajena, y transfigurarla. El último tema es una versión conmovedora de la balada folk “Scarlet Ribbons”, traspasada por sus raíces irlandesas.

Quizá valga la pena decir aquí que este álbum fue mi último intento significativo de acercarme a mi hermana. Sabía que le gustaban esas viejas canciones, y se lo regalé en una visita a Guadalajara. Nunca me enteré de cuál fue su opinión, aunque mi papá sí que le echó un ojo y se tomó la molestia, la siguiente vez que me vio, de burlarse un poco. (Tenía su lógica; nomás a mí se me podía haber ocurrido sembrar un disco de Sinéad en esa casa). El blanco de la burla de mi padre era el texto desesperado con que abre el cuadernillo del CD sobre la vulnerabilidad de los niños que han sido víctimas de abuso, con obvias referencias a la propia experiencia de O’Connor a manos de esa madre desquiciada a la que aún muerta seguía intentando amar. El texto va más allá: identifica al mundo entero y sus desgracias con ese niño violentado, y afirma que la respuesta es el amor, y Dios, “que es la Verdad – pero el Dios Verdadero”. La última pista del álbum es una extraordinaria declaración de guerra —espiritual— a la mentira, a los enemigos de Dios y de la valentía de Cristo; en específico, al Sacro Imperio Romano. Aquí no hay música: sólo la voz de Sinéad tendiendo un puente entre su rabia y su dolor y la experiencia de sus escuchas: “¿Puedes decir realmente que no sientes dolor como yo? ¿Hay alguien entre nosotros que no esté viviendo en el dolor?”. Y continua: “Dios dijo: ‘No traigo paz sino una espada’”. Sinéad traía, qué duda cabe, su propia espada en llamas, y estaba a punto de blandirla en un acto que haría ver a la rebeldía normalmente asociada con el rock como cosa de niños.

En estas declaraciones, O’Connor dejaba claro que tenía una misión, y no era nada más cantar. Quería denunciar el abuso infantil con la urgencia que el asunto exigía y llamar la atención sobre las secuelas que deja mediante una integración de sufrimiento personal y sufrimiento del mundo que, a su juicio, sólo podía curarse mediante la justicia y la intervención espiritual.

A lo largo de su carrera, dicho empeño le ganó muchos seguidores que habían experimentado un tipo similar de sufrimiento. En mi caso, sería absurdo pretender que no encontré también un eco en la voz de Sinéad, habiendo conocido mi propia versión del infierno familiar, pero me parece importante no simplificar este aspecto de su voz pública. Hacer público el dolor personal no es necesariamente una virtud. Lo extraordinario aquí es que alguien pudiera crear a partir de su dolor tanta belleza, tanta música nueva y apasionante, con inagotables talento e inteligencia. Lo que cautiva en Sinéad O’Connor, a un nivel profundo y verdadero, más allá de todos los escándalos asociados con ella en las noticias de la farándula, son su música y su voz puestas al servicio de una transfiguración, que ella siempre consideró espiritual, de la experiencia personal en un lenguaje universal que la trasciende.

Y el Papa

La pregunta de si acaso sus declaraciones de guerra eran la forma adecuada para adentrarse en la batalla, si la música no bastaba, no era del todo impertinente. Desde cierta perspectiva, su discurso podía parecer naíf, fuera de lugar, pero dicha pregunta surgía también de un enfoque práctico, por no decir prosaico, del intercambio social. O’Connor entró en la lidia en la única forma que podía, consciente de que gracias a su fama ahora tenía potencialmente al mundo entero como escucha, y si gritaba alto era porque su lucha era desesperada. Puesto que en sus alegatos (en entrevistas, en los cuadernillos de sus discos, en ese bonus track de Am I Not Your Girl), O’Connor hablaba con verdad, por impulsiva que pareciera la forma, pienso que la crítica surgía porque no se le estaba escuchando con atención; porque el mundo estaba poco acostumbrado a la franqueza de la inocencia —en el mejor sentido de la palabra— que suele ir acompañada de no poca valentía.

Lo verdaderamente sacrílego, para las personas que manejan los hilos de la industria musical, era estar diciendo estas cosas en ese contexto, donde lo que estaba en juego era, como siempre, mucho dinero. Pero Sinéad desafió a esa industria, como ya hemos visto, desde que grabó su primer disco, y lo siguió haciendo toda su vida. Recordemos cuando se rapó en la cabeza el logo de la banda Public Enemy para aparecer en la entrega de los Grammys, que entonces aún se negaban a reconocer el valor del rap o el hip hop; cuando se negó de plano, al año siguiente, a asistir a la ceremonia, porque la industria giraba alrededor de intereses comerciales y no artísticos. No le faltaba tampoco sentido del humor: cuando en Estados Unidos mucha gente quemó sus discos porque se negó a que se interpretara el himno nacional antes de una presentación suya, se disfrazó con peluca y lentes oscuros y acudió ella misma a la protesta.

Pero cuando desgarró la foto del Papa Juan Pablo II en vivo en el programa Saturday Night Live, en 1992, su cruzada pasó a otro nivel. La foto tenía para ella un significado personal: era la que colgaba en la habitación de su madre. O’Connor la recogió cuando fue con sus hermanos a poner sus cosas en orden tras su fallecimiento. El momento es bien conocido, se puede ver en You Tube, y se han escrito miles y miles de palabras al respecto: tras cantar a capela “Guerra”, la adaptación de Bob Marley del discurso a las Naciones Unidas del emperador etíope Haile Selassie en 1963 denunciando el racismo, y cambiando unas líneas para declarar la guerra contra el abuso infantil (prueba, para ella, de la existencia del mal en el mundo), Sinéad, mirando firmemente a la cámara, dice: “Combate al verdadero enemigo”, y rompe la foto del Papa. El Papa simbolizaba para ella ese mal, la institución que tanto daño le había hecho a Irlanda, donde el índice de abuso contra menores era entonces inmenso y perpetuamente ocultado por la Iglesia. El Vaticano, declararía O’Connor, era el primero en mentir al respecto, y responsable de muchas formas de violencia histórica, por poder y por dinero, en el nombre de Dios. Afirmaba también haber hecho lo que hizo para generar una discusión, y porque la Iglesia debía ser derrocada: “sus días están contados”, dijo varias veces. Su firme defensa de este acto ante los medios es eléctrica, sobreponiéndose con convicción y agudeza a su natural timidez. Sabía muy bien lo que estaba haciendo, y sabía que habría un precio que pagar.

De nuevo, la discusión pública alrededor del tema era un tanto frívola: que si el gesto era infantil, que si era una falta de respeto a la sensibilidad religiosa de otros. La mayoría de la gente simplemente no estaba escuchando, ni prestando atención al hecho de que esta acción provenía de una mujer profundamente religiosa.

El castigo no se hizo esperar, ejemplificado en el abucheo que recibió durante su presentación en el homenaje a Bob Dylan (su gran héroe) poco después, en una de las escenas más dramáticas en la historia del rock, pero O’Connor no se arredró. Cuando la gente le decía que acababa de destruir su carrera musical, solía responder, con no poco humor, que lo que había destruido era la carrera de la gente de la disquera, que ya no iba a poder sacar dinero de ella para irse a comprar sus casas de verano en alguna playa exótica. Para ella, dar este paso significó, entre muchas otras cosas, su verdadera liberación del yugo de la industria musical. Había dejado las cosas bien claras. Pudo seguir haciendo la música que se le daba la gana, y aunque no volvió a tener un número uno de ventas, eso era lo que menos le importaba. Podía causar ofensa constantemente, pero la dimensión de su talento significaba que nunca iba a dejar de cantar, de crear discos geniales, de colaborar con otros artistas en una efervescencia creativa que dio muchos frutos, y que siempre habría gente dispuesta a escuchar.

Si hace más de treinta años el gesto fue calificado, cuando menos, de infantil, la historia le ha dado la razón. Eso no quita que hayan sido treinta años en que, de una manera u otra, O’Connor fue vilipendiada e ignorada por muchos (muchos de los que ahora, tras su muerte, se dan golpes de pecho y hablan de su legado). A la larga, ser tratada constante y públicamente como una paria se cobró lo suyo, y más tratándose de una mujer que era tan fuerte como frágil, arrastrando las secuelas del abuso extremo del que había sido víctima. Para entender las consecuencias del incidente de la foto del Papa en su carrera, recomiendo ver la película Nothing Compares, de la que hablaré más tarde.