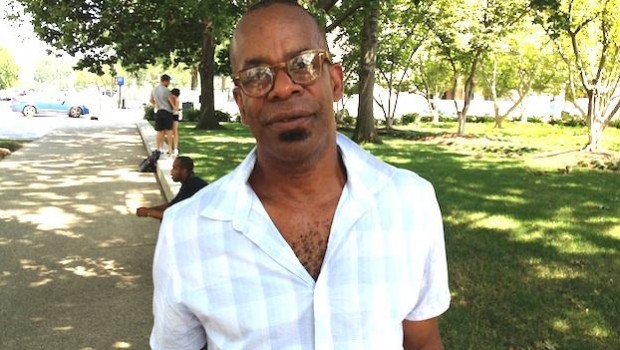

Elizabeth

H. G. Carrillo

In the twenty-eighth week of his third life, Raúl Crisantez remembers that at one time he was the prettiest man he knew. Guapisimo, una negra hermosa with sea-colored eyes once told him as she rubbed liniment into his muscles. That was in Havana. Knowing where and when, and in which life what is and what was what, is important to him.

His boss’ boss, Ms. Ruíz-Perkins, reminds him their meeting will only take a half-hour. She has a list of only thirty points, and they won’t have to go through this again for another twenty-seven weeks. She crimps her lips to look down and smiles when she looks back up at him.

Then you’ll be hired on permanently, she reminds him, and checks something on the clipboard. Eligible for a raise, she smiles, not realizing she is recapping their first conversation, one they had only three months ago.

You understand, don’t you? and she asks if anything she’s said so far is confusing to him. And he says, Not too much.

Memory is a great concern of hers. Though she seems to have forgotten that-still rehabilitating at the time, seeing a physical therapist four times a week-he had managed to get some of the highest test scores and secure the best recommendations of any aide she had hired. She had said so herself. Though she had also said, You’re a man and we don’t get many men and I’m not sure if this is a fit. But she seems to have forgotten that too now.

The teachers love you, she says as she checks off something. Though she is the only one that he has seen looking at his chest and arms. He has caught her looking at his ass in a mirror once when he was bending over to pick up one of the children. And is certain she has seen him catch her.

The children, they love you too, she checks and checks again, and smiles and says, You’re even good with the worst of the Mannys.

Which? he thinks.

There are four.

González, Suárez, Virgil, and Torres. A different intonation for each, all he has to do is say, Manny ven acá, and the right boy comes.

Suárez is all anger and hard shoes; tired or challenged, he’ll throw himself red-faced on the floor. Torres, needs to be watched, will eat anything, vomits a lot and seems to enjoy it. González always shares, plays well, though shakes and shrieks and can only be calmed, only feels safe sitting in Crisantez’s lap during thunderstorms; he occasionally wets his mat during nap time. Virgil stammers and wants to be Elizabeth.

Rosana Orosco likes to be in control of the tea set. She pours and asks around the table, Who will you be? The other girls know that she will always be María-Teresa, and Manny Virgil will say, I-I-I will be…I-I will be…I will be Elizabeth. At tea, he likes to wear a scarf on his head.

Ms. Ruíz-Perkins tells Crisantez that she appreciates his candor and honesty, and the patience that he displays. He is unsure of what she means, but thinks that it has something to do with the scar that crosses his face, bright red, from the left side of his forehead to the right side of his chin.

How did you get that? the Mannys Suárez and Torres-boys who play rough, like to tunnel under tables, desks and chairs; will hit, bite, scratch and throw things if allowed-will ask together nearly every day.

Did it hurt?

Not too much, he tells them, he doesn’t really remember. But says somewhere between his second and third lives he fell out of the sky cradling his welding gun in his arms like it was a baby.

The boys like to hear about the buildings he worked on. They beam when Crisantez rewards with a pat on the back of the head when every time that they ask he tells them it’s a very smart question, Where? One along Collins, another, the one he fell from on Brickell Avenue, right in the middle of downtown Miami, right in the middle of the afternoon where everyone could see. Why? the boys always want to know. Now that’s Why? and Why? is Why? Very different than Where? Where? is Where? he tells them, Why?…well, that is always something else. So he always gives a different reason.

For two egg and olive sandwiches and a thermos full of sopa de chorizo, he told them when they asked this morning, You know I can’t do without lunch. It was falling, he says. And the boys laugh and tell him he’s loco.

Crisantez has seen them each try on his limp, not in fun unless one catches the other one doing it. Just doing to do it for a while. They forget and ask again the next day or an hour later, try on his limp for a while and forget again.

He always says the same thing never knowing which parts are true and which parts were told to him. He remembers the building, and that there had been waves of heat coming off of the asphalt, but beyond that it’s not one of the days that he has wanted back necessarily. Not one he has missed he’s certain because he remembers where it happened, can point to the ordinals on a street map.

He asks his boss’ boss to spell candor, and he writes it down in the black notebook he keeps in his breast pocket to look up later. Ms. Ruiz- Perkins crimps her lips any time he takes it out. Her nylons sigh as she unfolds and re-crosses her legs. She twists her wedding ring on her finger. He knows she knows that sometimes it is all the memory that he has.

Worn thin at the end of the day, he sometimes needs to check the map he has drawn in the back of the Moleskine that will lead him back to his brother-in-law’s house where he has his own bathroom and kitchenette over the garage. Phone numbers, including his sister’s new one, though he rarely called it, are in along the front inside flap, though he has drawn a map in case he ever needs to find her or when he wants to think of her in her new life. Next to it is the diagram that he drew for the arrangement of tables and chairs for craft time. And next to it, the one for snacks and lunch, and then the one that lines them all up against the far wall.

The time that Monica Umpiere is to have her medicine and how much, which parent is to pick up David de Consuelos on what day are things that present themselves as immediate, urgent as breathing. Names of books, movies, streets, however, come and go as easily or rest under the surface as mutely as a dull headache. Avis is the woman who serves breakfasts at the diner he likes. The state of Florida covers sixtyfive thousand seven hundred and fifty-eight square miles; eleven thousand seven hundred and sixty one of them are water. Its flower is the orange blossom, its song Swanee River. Yet some facts in this new life can be slippery and unavailable and he’ll find himself reciting his phoneor social security number to keep the rest of the world anchored.

Prompt, positive and orderly. A very good organizer of both time and person. Traits Ms. Ruíz-Perkins says she finds very necessary in the job, but she finds unusual in a man. She checks twice before writing something down. Though, she chastises, a couple of times I’ve passed through and seen you rough-housing with the kids before nap time, and that gets them riled up.

Though she doesn’t indicate if this is good or bad, she crimps and uncrosses and re-crosses while he writes this down. I’m certain that you’ll remember that, she says, You’re a marvelously inventive man, all the teachers say so.

But he always takes notes. It’s what he does.

If he’s been to a game, he’ll take down the vibration and hum of the seats, the sizzle in the air, and before naptime instead of reading to them as the other aides have, he tells the story of Ewaldo: The Ball Who Found Himself in Another Universe. They sometimes sit next to a horse he’s found in one of the paintings in the museum. He asks them to lie on their mats, close their eyes, feel where it’s smooth and where it curves, stroke its mane, and ride it over the green hill in the background, under the sun, over hill and hill and hill and another. They never ask why, they just go. He’ll ask them to jump on the back of a red ant, and help him build his mound a grain of sand at a time. He tells them to be choosy; Yellow and pink ones make for nice outside walls; Green, brown and gray and blue ones would make the inside cool and smooth and easy in the hot summer days. They all nod and agree it’s like living on the back of a turtle under a leaf, like he says.

Sometimes after the rains, he will take them outside to show them the little fishes that swim in the puddles left behind. He’ll tear pages from the center of the notebook and fold them into boats.

The boys tend to want to know if he has a boat. The girls ask if he knows how to sail, if he goes out on boats. And he says, Not too much.

But they always press him to tell about the time he was a fish. They ask, Where? and wait for him to point three fingers downward to make the pendulous curve in the state, and, with his other hand, point to a space below it where they all imagine the plump emerald-colored swells, the kind he has told them that remind you of jelly candies but are brackish and burn. When? they ask.

And he tells them that between his first and second lives he spent twenty-three days on a raft. They ask about goldfish, and he tells them about schools of remora glittering under his belly, green and blue and pink and yellow. They ask about angelfish like the ones in the aquarium in the classroom, and he tells them about the sailfish-all blue and golden, green and glimmer-that spun out of the water and flipped him in. And about the gallons and gallons of seawater he swallowed, until he was gray and gill, and he felt pink and raw inside when the CoastGuard pulled him out like a tuna.

Were you scared? they ask and he tells them, Not too much. And, Not too much, is what he answers when Ms. Ruíz-Perkins asks if he has any questions at this point. It hangs in the air between them for a while. She crimps and re-crosses. And he wishes he were sleek, delicate and refined, and felt less like a foot that’s come out after months in a boot.

And it’s her perfume as she shifts and checks and crimps and recrosses that makes him want to tell her that in his first life he had been a boxer. Boxeador De Medalla De Oro. Treinta y Nada. Nada, nada, nada. A reporter for Prensa Latina called him Unbeatable.

He writes unbeatable in the notebook, she looks up smiles and looks down and checks again.

He had ridden on the shoulders of very fine men, he wants to tell her, and been a welcome visitor in the bedrooms of their wives and girlfriends. But, he also wants to tell her, You can only do that so long before you fall out of that sky too. Wants to show her something about him in this life that shows her he is just as pretty as she. But he doesn’t because he knows it’s not on her list, and he knows it wouldn’t necessarily make her happy. It belongs to another life.

She checks and checks and checks, pressing hard. The flourish of her hand is official, accurate. Her point sharp sharp sharp, Now Now Now, it insists in the air, as she shakes her bracelets down onto her wrist again and pulls her hair away from her eyes with her free hand, there are to be no mistakes. She reads over what she has written, crimps and smiles and asks, Next year?

Where do you see yourself a year from now? she says as if he hadn’t heard. In low voice, almost a whisper, sweet and slow, fat big words, as she leans in towards him in the same way that she would had he taken a ball or a truck or wouldn’t sit when he was told or simply wouldn’t give her something he had that she wanted.

Her blouse falls open a little and her necklace leans forward and teeters as she places her hand on her wrist and uses herself as an example. Where would she be, what would she do. She lists the people she would want to be in contact with and the car that she would like to be driving. There is a bit of powder between her breasts and the bra that she is wearing is pink.

And it is not that he doesn’t understand the question, no need for him to see how it fits on her. He listens, but it’s her hand on his wristnot too long, but long enough-it’s the question, like the uncrossing and re-crossing of her legs, the crimping of her lips that’s clear and coils something sad in him for her that makes him hope that in this life she is the love of someone’s life, and in her next life someone is the love of hers, and in the lives that follow she is able to remember each of the previous as if they were seconds ago.

He doesn’t pull back. He lets her.

It’s not that he doesn’t understand, it’s just something he’s never felt, so he lets her and lets her. The same way that he looks away when Manny Torres wants to sneak a little paste, or Manny González will come sit in his lap on a day there isn’t a cloud in the sky, and he will let Manny Suárez scream and throw his legs for a while before he goes over to soothe him; the same way-after the room is set for naptime and the teachers have gone to lunch-Manny Virgil will get the white tulle skirt from the dress-up box and will bring Swan Lake to be put into the stereo, and in the lulling of the orchestra, twirl around the mats of sleeping children, stop and reach both his arms for what Crisantez thinks looks like anything possible before he begins again.

Posted: April 6, 2012 at 7:38 pm