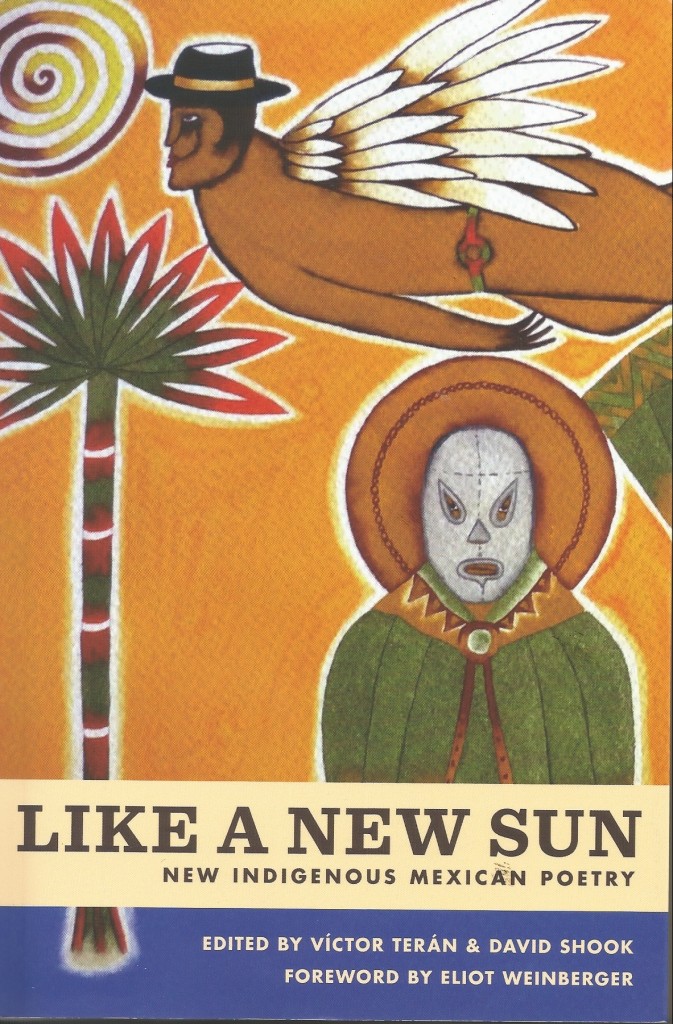

Like a New Sun

Eliot Weinberger

The arrival of the Spaniards in Mexico has often been compared to the appearance of extraterrestrials (more exactly, extra-terrestrials before the age of science fiction, before we began to imagine what they might be like). The bearded white men with their horses and guns corresponded to nothing in the Mexican worldview; and, most disastrously, the autoimmune systems of Mexican bodies had no experience with Spanish microbes. It has rarely been said, however, that this was also an encounter of mutually incomprehensible poetics. (If the conquistadors were largely illiterate soldiers, some of those who followed them, particularly a few of the priests, had both education and curiosity.)

Spain in the 16th century was writing traditional ballads and romances, and odes and elegies and eclogues inspired by the Latin. The sonnet, newly imported from Italy, was the rage. Mexico in the 16th century—to speak of only one of its poetries, the Aztec— had eleven sub-genres of lyric poetry that remain known to us: eagle songs, ocelot songs, spring songs, flower songs, war songs, divine songs, songs of orphanhood (also known as “philosophical reflections”), tickling songs, and songs of pleasure. The great religious Spanish poets of the period, Fray Luís de León and San Juan de la Cruz (St. John of the Cross) were humans who wrote in praise of God. The great religious Aztec poetry—preserved in the Cantares Mexicanos—came as a gift directly from the gods to humankind. More astonishingly, it is believed that the poems were themselves a kind of god, venerated ancestors summoned to earth by the supplications of the poets.

The Aztec figurative system famously yoked two elements to form an unexpected third: cacao was “heart and blood,” misery was “stone and wood,” fame was “mist and smoke,” pleasure “heat and wind.” (This tradition of conjunctions, seen through the eyes of Surrealism, would be reinvigorated, four hundred years later, by Octavio Paz.) A person could be a feather, jade, a cypress, a flute, a gold necklace, a city. Fray Diego Durán, one of the first priests who was interested, unironically said that their poems are “so obscure that there is no one who really understands them— except themselves alone.” Spanish poetry “conquered” Mexican poetry in the centers of cultur e, with the unforeseen consequence that the greatest Spanish-language poet of the second half of the 17th century (and indeed for two hundred years after that) was a Mexican: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. But poetry composed in the scores of native Mexican languages carried on in the countryside, along with traditional customs, beliefs, and ways of making art. Most of this poetry was, of course, orally transmitted, and was unknown outside of its communities until anthropologists and others began transcribing and translating the poems in the twentieth century. It is a poetry without a literary history, in the sense that it arrives to us late in the story and we do not know how it evolved over the centuries—as though the earliest known English-language poet was William Carlos Williams. And it is a poetry without criticism, in that we rarely know its poetics or its standards—the details of its composition, or what its listeners considered to be good or bad.

e, with the unforeseen consequence that the greatest Spanish-language poet of the second half of the 17th century (and indeed for two hundred years after that) was a Mexican: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. But poetry composed in the scores of native Mexican languages carried on in the countryside, along with traditional customs, beliefs, and ways of making art. Most of this poetry was, of course, orally transmitted, and was unknown outside of its communities until anthropologists and others began transcribing and translating the poems in the twentieth century. It is a poetry without a literary history, in the sense that it arrives to us late in the story and we do not know how it evolved over the centuries—as though the earliest known English-language poet was William Carlos Williams. And it is a poetry without criticism, in that we rarely know its poetics or its standards—the details of its composition, or what its listeners considered to be good or bad.

In recent decades, there has been an extraordinary new development in Mexico’s indigenous literatures. Bilingual writers, educated in Spanish and conversant in Western modernism, are choosing to write in their native languages. As these are contemporary writers, their poetry and fiction is disseminated orally not only in live performance but also on radio shows, and, for the first time in these histories, in books and language-specific magazines. Some of the poets in this book use their native language as a way of enriching the modernist lyric. Others use modernism to re-imagine traditional forms.

What is happening in Mexico is being mirrored in many other countries where indigenous languages survive. It is partially a matter of ethnic pride. In the globalizing world, there is a countercurrent that is emphasizing the local, celebrating what is different in the face of the monoculture, adapting the old ways in an era of relentless novelty. But it is also a culmination of modernism itself, the rallying cry of which was Joyce’s “Here Comes Everybody.” Twentieth century painting and sculpture is inextricable from its discovery of new forms in African and Native American art, or the stories, poems, and myths of tribal cultures that permeate modern literature. (For some decades there was, in France, a very blurred line between the Surrealist and the anthropologist.) Yet this was, in the last century, all one-directional: the indigenous feeding the cosmopolitan West. We are now at a moment—still in its early stages—where inspiration is flowing the other way. As this book demonstrates, the poetry written in Spanish, English, and French is one part of a complex of ideas and perceptions that is invigorating new ways of writing in Mazatec, Zapotec, Zoque, and Nahuatl, which may in turn lead to something else, somewhere else.

***

The following poems belong to the anthology compiled by Víctor Terán & David Shook

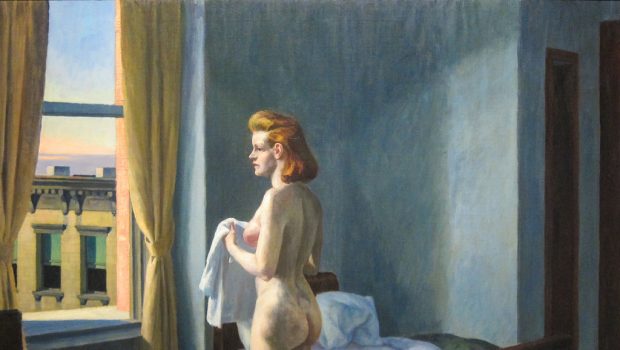

I Know Your Body

By Víctor Terán

Translated from the Isthmus Zapotec by David Shook

I know your body,

entirely I know you.

If you were a city

I could give perfect directions to wherever they asked me.

I like all of your body,

I like to see you talk, laugh,

move your head. Your two well-rounded hills

are the honey of bees, where my lips celebrate to the gods. I would have liked to continue

storming your forest, lodgings made deliberately for a nice death.

You were created with love,

your body is worthy of praise. What an honor to have lived, to have been. I am no longer bothered

when men turn to look at you,

I am no longer impatient when you undress.

You are a stag in the air. A raft of flowers

that snakes across the river by morning.

There is no part of your body that I do not know, there is no part that I do not like. I want

to keep being

the light stunned at the look of your white

roundness of flesh. I want to keep

living

in the beautiful city

that you are.

GUIDÚBILU’ RUNEBIA’YA’

Guidúbilu’ runebia’ya’,

guidúbinaca peou’.

Pa ñácalu’ ti guidxi

ratiicasi ninabadiidxa’ cabe náa

naa nulué’ pa neza riaana ní. Riuuládxepea’ guidúbilu’,

riuuladxe’ guuya’ guiní’lu’, guxídxilu’, guzeque yannilu’. Dxiña yaga guiropa’

dani zuguaa ndí’ xtilu’, ra guyaa’ dxiqué rigucaa’ ruaa bidó’. Ñacaladxe’ rua’

ñuá’ ne niree ndaani’ guixhidó’ xtilu’,

ni guya’ dxiiña’ guiluxe guendanabani ndaani’. Biza’naadxi’ bido’ guzana lii, qui gápalu’

ra guidiiñeyulu’. Binnindxó’ nga naa

ti bibane’ lii, guca’ lii. Yanna ma cadi naa ridxiiche’ gudxigueta lú ca nguiiu ra zedi’dilu’,

ma cadi naa racalugua’ cueelu’ lari.

Ti bidxiña lubí nga lii, ti balaaga’ guie’

ziguite yeche’ lu guiigu’ ti siadó’.

Gabati’ lii nou’ qui ñunebia’ya’, nou’

qui ñuuladxe’. Pa ñándasi ñácarua’ biaani’ ruxheleruaa ruuya’ ca nduni yuxido’ quichi’

beelaxa’nalu’. Pa ñándasi nibeza rua’

ndaani’ guidxi sicarú ni nácalu’.

The Owl

By Briceida Cuevas Cob

Translated from the Yucatec Maya by Jonathan Harrington

The owl arrives.

It crouches on the wall.

Meditating.

Whose death should it announce

If no one lives in this village?

The fossils of the people have never been moved.

The moon paints the graves of the overgrown cemetery. The owl

calls out a song to life.

Refusing to foretell its own death.

XOOCH’

Ts’o’ok u k’uchul xooch’.

Tu mot’ubal yo’ koot.

T’uubul tu tuukul.

Máax ken u tomojchi’it

wa mix máak ku k’iin ti’ le kaaja’.

U xla’ báakel máako’obe’ chen ka máanako’ob. Uje’ tu bonik u muknalilo’ob ch’een k’aax

ts’o’ok u káajal u lu’uk’ul tumen loobil. Xooch’e’

tu xuuxubtik u k’aayil kuxtal. Tumen ma’ u k’aat u k’ay u kíimil.

These poems belong to the book Like a New Sun which features poetry from Huastecan, Nahuatl, Isthmus Zapotec, Mazatec, Tzorzil, Yucatec Maya and Zoque Languages. Published (and copyright) by Phoneme Media

Posted: August 7, 2015 at 6:57 am

Thank you for this.