The New Conquest

Mark Lacy

As an American, Mexico is becoming familiar—not because of the migration of Mexican people to the United States, or the influence they have had on our culture, as we are becoming a bilingual nation.

The United States is having an effect of its own on Mexico. Our trends and celebrity icons are featured on Mexican television. Our brands are in Mexican stores. But most of all, our transnational businesses are spreading across Mexico like wildfire.

As Americans, we recognize the signs popping up all over Mexico; after all, they are displayed up and down most of our own streets and highways.

Many Americans are unaware of this transformation, which is only apparent to those of us who travel in Mexico. It is strangely welcomed by many of the American travelers, who like to feel at home wherever they go; they will travel to an interesting place only to sit comfortably in a restaurant just like the one they frequent back home. Consistency is a large part of American life.

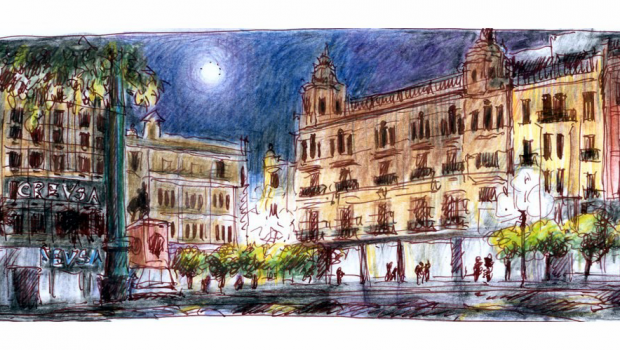

I realized the prolific American logos would soon be found all over Mexico when I visited Puebla a few years ago. On the anniversary of Mexico’s struggle for independence I discovered the Golden Arches on Puebla’s town square. McDonalds, with its cartoon symbol of modern conquest, Ronald McDonald, was full with young Mexican customers while other local eateries starved for business. A fellow traveler assured me, “Mexican culture is very strong; it will survive.”

To understand how long Mexico’s culture of independence might survive we can survey the state of American independence. Americans have been through a century-long conquest by many of the same corporate invaders that are now spreading out across Mexico.

People of the United States once centered much of their activities around town squares, where independent stores and venders thrived, where townspeople built social networks and carried out American traditions. Even our early chain stores, as they were called, like Kress and Woolworth’s, brought their storefronts to the town center. That was where the people were, actively talking and trading.

Through the middle of the twentieth century, the United States pioneered excellent highway infrastructure and communication technologies—network television and national phone systems—connecting the nation like no other before it.

Americans benefited from the vast possibilities the new coast-to-coast highways offered and followed their own interests to build unique businesses, many still romanticized on postcards about old Route 66. Individual enterprise across the land of opportunity resulted in broad distribution of the nation’s growing wealth. The famous American middle class truly existed for many of the nation’s post-World War II years. Americans even shared in the revenues from distribution and sales of innovative national products.

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s vision of the Interstate highway system was the ultimate prize for automobile manufacturers and oil refiners. Early on, it allowed Americans mobility they had never known before. Many fledgling corporations developed as the national highway system grew, but ultimately only a few would capture the American market with the establishment of tens of thousands of sales and service outlets across the country. The limited access, divided freeways would unwittingly limit access by average Americans to the trade superhighway of today.

Investment by the U.S. government was responsible for the prosperity much of the nation experienced. Communities even welcomed the added boom of investment by outside businesses that competed for American discretionary dollars. As American corporations grew larger in the 1960s and 70s, their profit-taking was difficult for most American communities to sustain.

As growing big businesses raked profit from small towns and historically disadvantaged communities, collecting it in the limited pockets of owners and shareholders, the new-found opportunity for independent business ownership waned. The American dream changed from small business ownership to middle management positions in the glass towers of the thriving corporate world. Success was measured by the ability of the sprawling companies to set up shop in neighborhoods and small towns across America to collect the nation’s wealth. Ruthless consolidation of the nation’s industries was the chosen method of ensuring the highest profits.

Developers built great indoor malls where national businesses attracted young Americans across the country to buy the things they saw on TV. The big names of yesteryear even reemerged there. As Woolsworth’s five and dime stores disappeared, they opened up in malls as Foot Locker, with US $100 Nike shoes that American teens sometimes killed each other for, and Kress anchored the biggest mall in the Caribbean with its Tiendas Kress expansion in Puerto Rico. Even Santa Claus, who once entertained the simple wishes of humble children on the wintry-cold town squares, moved into the mall for the holidays, where Americans have everything they want in air conditioned comfort.

The network of store chains relies entirely on the nation’s roadways. What was paid for by the public has proven tremendously beneficial to the wealthiest Americans, many of whom today seek to reduce their taxes by crying that paying taxes sti- fles their further investment in the economy. Their luck may have run out, along with the supply of capital communities once provided.

Most Americans cannot afford what this prosperity offers, certainly not at the level of consumption they enjoy. Consolidation of the nation’s wealth has resulted in more than one million millionaires and 371 billionaires (according to Forbes in 2006), but a working poor population of more than 37 million people struggle to make ends meet. Poverty in the country is growing as more than 13% of United States citizens fall below a poverty threshold that is difficult for many others to surmount.

Many Americans are blissfully ignorant or uninformed about these issues, which receive little coverage by a mass media that knows too much to dare reveal the truth on a scale that might wake up the nation. Tax Day, April 15, is the day many Americans dread most, but oddly enough, they feel a special sense of duty to spend big on Black Friday, the day following Thanksgiving, when people are led to believe American businesses move their accounts from the “red” loss column to the “black” profit column. The success of the nation is now reported by the profits of a few major businesses during the holiday season. For top investors it is measured daily by stock market reports and ultimately tallied in the annual Forbes Fortune 500 list. But, as a measure of success, the Fortune 500 fails to recognize the security of the source of business profits —the U.S. consumers, who are in debt more than US $800 billion. Or the other source of their wealth – the U.S. taxpayers (largely the same), whose government owes almost US $9 trillion.

With unsustainable profits built on debt, business and government strategists have pursued a solution—greater access for U.S. companies in foreign markets. Most foreign markets have a tremendous amount of territory to conquer and Mexico ranks very high (13 by Gross Domestic Product as ranked by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund in 2005; Brazil is number 10; Brazil and Mexico being the two Latin American nations in the top 20).

The public largely has not connected the concept of its debt with the drive by business leaders for free trade. The term “free trade” evokes positive notions for most Americans, as they believe foreign investment will build up other nations and the resulting benefits will be democracy and a middle class—the American way.

Most Americans consider their country, the United States, to be the greatest nation on Earth. It makes sense to them that all other nations should strive to be like us. Americans are easily persuaded to think that what is good for business is good for America; they credit big business with improving their lives and the nation.

Simultaneous to the rise of big business was the development of health and safety measures to protect the public. Local and state regulation of vendor licenses and food inspections increased expectations on businesses to care more for the public they serve. This achievement was capped by the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) of 1970, which prompted the World Health Organization’s 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion to bring higher standards to international communities.

It wasn’t the stainless steel countertops or shiny translucent plastic signs lit by fluorescent bulbs that made the point-of contact vendors rise to higher standards in America, but rather the demand for consumer protection and government investment in it. Local governments played an important role in maintaining high standards for businesses where the absentee ownership collected its profits in distant cities.

Not to be overlooked, a positive impact of U.S. national corporations has been a reduction in discriminatory practices, at least on the customer side. The far-away ownership rarely cared about the race or identity of its customers. But narrowly- owned businesses have not expanded opportunity for all minorities in the United States; rather, African Americans and Mexican Americans lag behind.

Americans often mistakenly idealize the merits of big business. Our inequality has been widened to such an extent that multinational corporations are the only ones that can afford to pay celebrities or sponsor professional sports. Even most community endeavors require corporate support to meet basic operating costs or to interest the media. Americans have become more dependent than they realize in order to have their freedoms.

We aren’t engaged in a globalization process to extend our values to other nations, but rather a desperate struggle to find solutions to our own debt. The globalizing process of transnational businesses diminishes our sense of responsibility to the community while increasing our indebtedness to the wealthy.

As nations that have been beleaguered by sharp economic disparity wager on trade agreements for the prospect of a new middle class, the requirement for massive sales of merchandise and competitive shipping solutions will demand cheap labor. Those who start from a disadvantage will likely become the cheap labor solution, as Mexico has witnessed in its maquiladora industry.

The greatest disadvantage occurs when outside owners are most successful in a community with no assets. Their profits may yield little reinvestment for the community. The most effective way for a community at risk to raise its standards against its potential losses, as outside businesses remove tidy profits, is to return to a community model of local spending. Whether it is dollars or pesos, money that quickly leaves the community will be transacted fewer times than money that is transacted locally (magnifying in value with each exchange). As spending on local goods and services increases, the collective income of the community increases.

As Americans have become familiar with a business model that seeks its riches in faraway places, where communities that run out of resources count for very little, Americans must understand that there is no alternative for many Mexican people but to seek work in the United States; it’s where the money is. What they bring with them is the kind of pride in their community that independent Americans once knew.

– Mark Lacy is a photographer and the director of Houston Institute for Culture.

Posted: April 8, 2012 at 9:35 pm